Facts, information and articles about John Brown’s Raid On Harpers Ferry, a one of the causes of the civil war

Raid On Harpers Ferry Facts

Date

October 16–18, 1859

Location

Harpers Ferry, (West) Virginia

Forces Engaged

88 US Marines (USA)

21 Raiders

Casualties

2 Marines

10 Raiders

Raid On Harpers Ferry Articles

Explore articles from the History Net archives about Raid On Harpers Ferry

» See all Raid On Harpers Ferry Articles

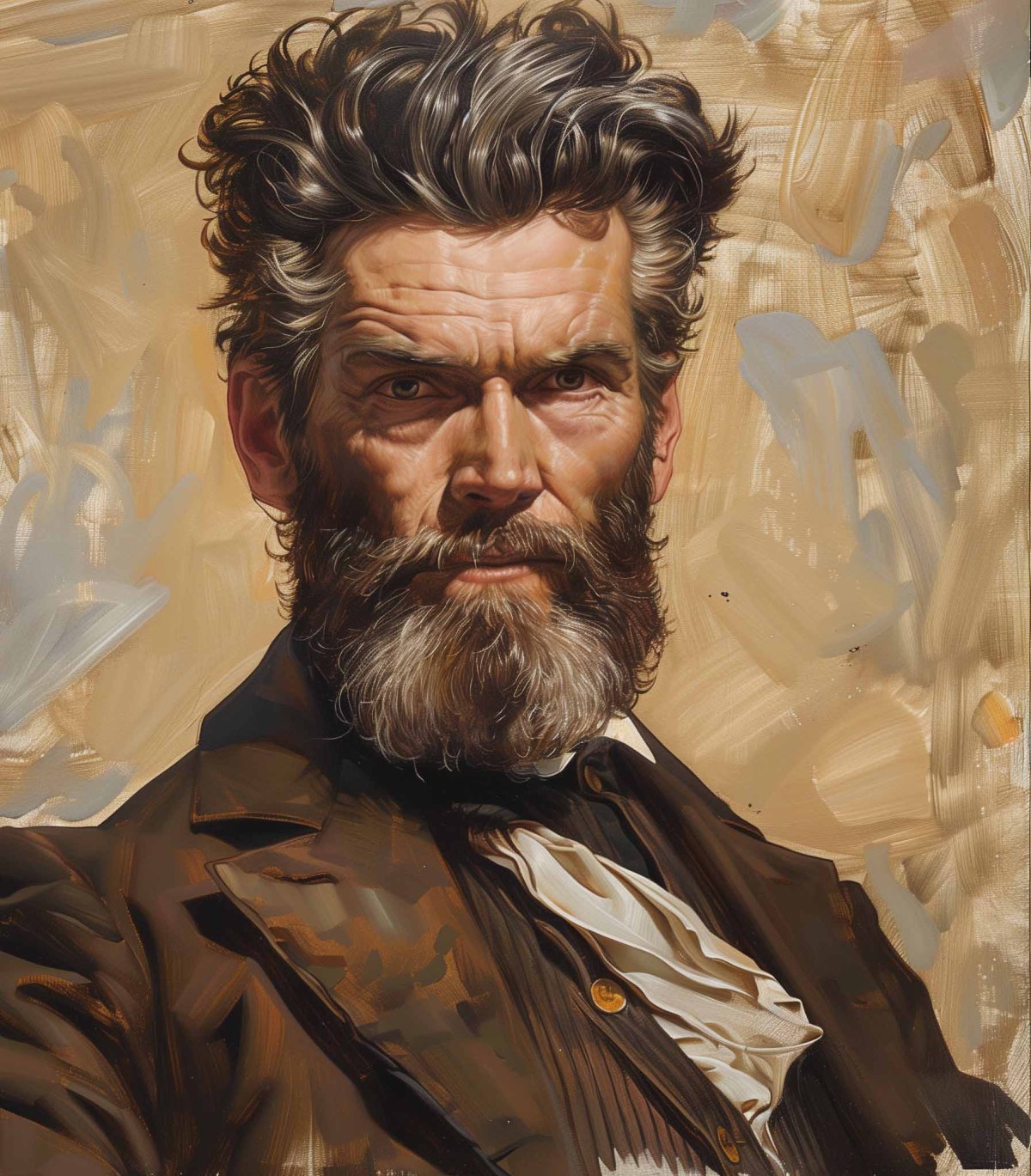

Raid On Harpers Ferry summary: The Harpers Ferry raid conducted by fanatical abolitionist John Brown and 21 followers in October 1859 is considered one of the major events that ultimately led to the American Civil War. Brown was hanged December 2 for murder and treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia.

John Brown Assembles An Army

The 21 men accompanying Brown in what he dubbed the "Provisional Army" were a mixed lot, united only in their hatred of slavery. Five were black and 16 white. The raiders’ second-in-command was John Henry Kagi, a former schoolteacher. William Leeman was a shoemaker from the state of Maine. Stewart Taylor was Canadian-born. John E. Cook came from a well-to-do family. One of the black men, Dangerfield Newby, hoped Brown’s actions would help him to rescue his wife from slavery. Two others, John Copeland and Lewis Leary, were former slaves like Newby.

Brown himself had operated tanneries, attempted (unsuccessfully) to become a minister, and had tried and failed at various other business enterprises. In Kansas Territory, he and a small group of fellow abolitionists had killed five pro-slavery men near Pottowatamie Creek. When he discussed his plans for a raid on the arsenal at Harpers Ferry with Frederick Douglass, in August 1859, Douglass warned him, "You’ll never get out alive."

John Brown at Harpers Ferry

After sundown on Sunday, October 16, 1859, Brown and his men left a farm he had rented under the name "Isaac Smith" in Western Maryland, across the Potomac from Harpers Ferry. Walking through a heavy rain, they reached the town in darkness, capturing several watchmen and cutting telegraph wires. Hayward Shepherd, a black man who was a Baltimore & Ohio Railroad baggage handler, confronted them and was killed, the first fatality of the raid.

They seized the arsenal and armory, as well as Hall’s Rifle Works, a private enterprise, and took 60 hostages from among prominent men of the area, including Lewis Washington, a great-grand nephew of George Washington. If Brown hoped the slaves of these men would join his revolution, he was disappointed; none did. The raiders also made a serious mistake when they detained a B&O train for five hours, but then let it go on to Baltimore. The conductor notified authorities in Washington after the train reached Baltimore around noon on the 17th.

The Occupation of Harpers Ferry

When armory workers arrived on Monday morning and discovered Brown and his raiders had taken over the buildings, word went out and local militia companies assembled. They surrounded the armory. The raid’s second fatality occurred around 7 a.m., when Thomas Boerly of Harpers Ferry was shot and killed. Before the day ended, two more local residents, George W. Turner and the mayor of Harpers Ferry, Fontaine Beckham, were also killed.

Brown, with one of his sons and four other riflemen, took nine of the prisoners and holed up in the armory’s fire engine house, a smaller structure about 30×35 feet. Later, this became known as "John Brown’s Fort." Several of his accomplices tried to escape; some succeeded, others were killed in the attempt.

Robert E. Lee Takes Command at Harpers Ferry

When the B&O conductor’s message about what was happening at Harpers Ferry reached President James Buchanan in Washington. A detachment of 86 U.S. Marines was dispatched to Harpers Ferry, led by First Lieutenant Israel Green and accompanied by Major William W. Russell. The major was the paymaster for the Marine Corps, but as a staff officer he could not command the force. Secretary of War John B. Floyd had placed overall command in the hands of a former superintendent of West Point, Army Lieutenant Colonel (brevetted colonel) Robert E. Lee, who had come up from Washington, accompanied by Lt. J.E.B. (Jeb) Stuart of the 1st U.S. Cavalry, who had carried Floyd’s message to Arlington to summon Lee. The two Army officers, riding a special train ordered for them by B&O president John W. Garrett, caught up with the Marines at Sandy Hook, about a mile and a half east of Harpers Ferry.

Upon reaching Harpers Ferry, Lee determined that many of the local militia soldiers in the town were drunk. He promptly ordered all saloons closed.

On the morning of the 18th, Lee sent a summons to the insurgents ordering them to lay down their arms and surrender. When, as he expected, they rejected his demands, he sent Lt. Green, clad in his dress uniform, and 12 of the Marines to storm the fire engine house; Major Russell accompanied them, armed with nothing but a rattan stick. Three of them were furnished sledge hammers for breaking in the door. Once inside, they were to attack with bayonets, lest stray bullets hit some of the hostages. Lee explained to the Marines how they could distinguish the insurgents from the captives and ordered the storming party "not to injure the blacks detained in custody unless they resisted." Several slaves had been taken along with their owners and armed when Brown’s men rounded up hostages.

In his report to the Secretary of War the following day, Lee described the action of the storming party:

"At the concerted signal the storming party moved quickly to the door and commenced the attack. The fire-engines within the house had been placed by the besieged close to the doors. The doors were fastened by ropes, the spring of which prevented their being broken by the blows of the hammers. The men were therefore ordered to drop the hammers, and, with a portion of the reserve, to use as a battering-ram a heavy ladder, with which they dashed in a part of the door and gave admittance to the storming party. The fire of the insurgents up to this time had been harmless. At the threshold one marine fell mortally wounded. The rest, led by Lieutenant Green and Major Russell, quickly ended the contest. The insurgents that resisted were bayoneted. Their leader, John Brown, was cut down by the sword of Lieutenant Green, and our citizens were protected by both officers and men. The whole was over in a few minutes."

Casualties in John Brown’s Raid

The Marine killed was Private Luke Quinn, the third man through the door, shot through the abdomen. The man behind him, Pvt. Mathew Ruppert, suffered a slight facial wound. Lieutenant Green inflicted a deep cut on the back of John Brown’s neck, but the fanatical abolitionist was still alive. No captives were harmed, and there were no further deaths among the townspeople.

Among the raiders, two were bayoneted to death in the fire house. In all, 10 raiders died of wounds received during the raid on Harpers Ferry; the first to die was Dangerfield Newby, who had hoped to win his wife’s freedom. Six more were hanged, and five escaped, several of them later serving in Union regiments during the Civil War.

Stuart, with a few Marines, was sent to the farm Brown had rented. They found Sharp’s carbines, revolvers, "a number of sword pikes, blankets, shoes, tents, and all the necessaries for a campaign," as Lee described it.

Robert E. Lee on John Brown’s Motives

Of Brown, Lee wrote, "He avows that his object was the liberation of the slaves of Virginia, and of the whole South; and acknowledges that he has been disappointed in his expectations of aid from the black as well as white population, both in the Southern and Northern States. The blacks, whom he forced from their homes in this neighborhood, as far as I could learn, gave him no voluntary assistance. The servants of Messrs. Washington and Allstadt, retained at the armory, took no part in the conflict, and those carried to Maryland returned to their homes as soon as released. The result proves that the plan was the attempt of a fanatic or madman, who could only end in failure; and its temporary success, was owing to the panic and confusion he succeeded in creating by magnifying his numbers."

That evening, a false rumor that a band of men had attacked a home in Pleasant Valley, Maryland, sent a number of families scurrying to Harpers Ferry for protection.

In The Aftermath Of John Brown’s Raid On Harpers Ferry

Brown was convicted of murder, insurrection and treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia. He was hanged at Charles Town, the seat of Jefferson County, near Harpers Ferry on December 2, 1859. His attempts to capture the federal arsenal and free "all the slaves in the South" had failed, but abolitionists quickly made him into a martyr for freedom. It is often said he accomplished with his death what he could not have accomplished while living.

Robert E. Lee would leave the U.S. Army in the spring of 1861 and win eternal fame as the commander of the largest Confederate army. His chief of cavalry with that army would be Jeb Stuart. Israel Green would also resign his commission to join the Confederacy, though he was offered a colonelcy in the militia of his native Wisconsin. He also rejected an offer to be a lieutenant colonel in Virginia’s Confederate infantry, choosing instead to accept the rank of captain in the Confederate States Marine Corps. He rose to the rank of major and became adjutant and inspector.

Of the principal U.S. military officers at Harpers Ferry, only Maj. Russell did not go to the Confederacy. He was still Paymaster of the United States Marine Corps when he died in October 1862, three years after John Brown’s Harpers Ferry raid. Learn more about John Brown