Facts, information and articles about Lyndon B. Johnson, the 36th U.S. President

Lyndon B. Johnson Facts

Born

8/27/1908

Died

1/22/1973

Spouse

Claudia Alta "Lady Bird" Taylor

Years Of Military Service

1941-1942

Rank

Lieutenant Commander

Accomplishments

Silver Star

Presidential Medal of Freedom

36th President of the United States

Lyndon B. Johnson Articles

Explore articles from the History Net archives about Lyndon B. Johnson

» See all Lyndon B. Johnson Articles

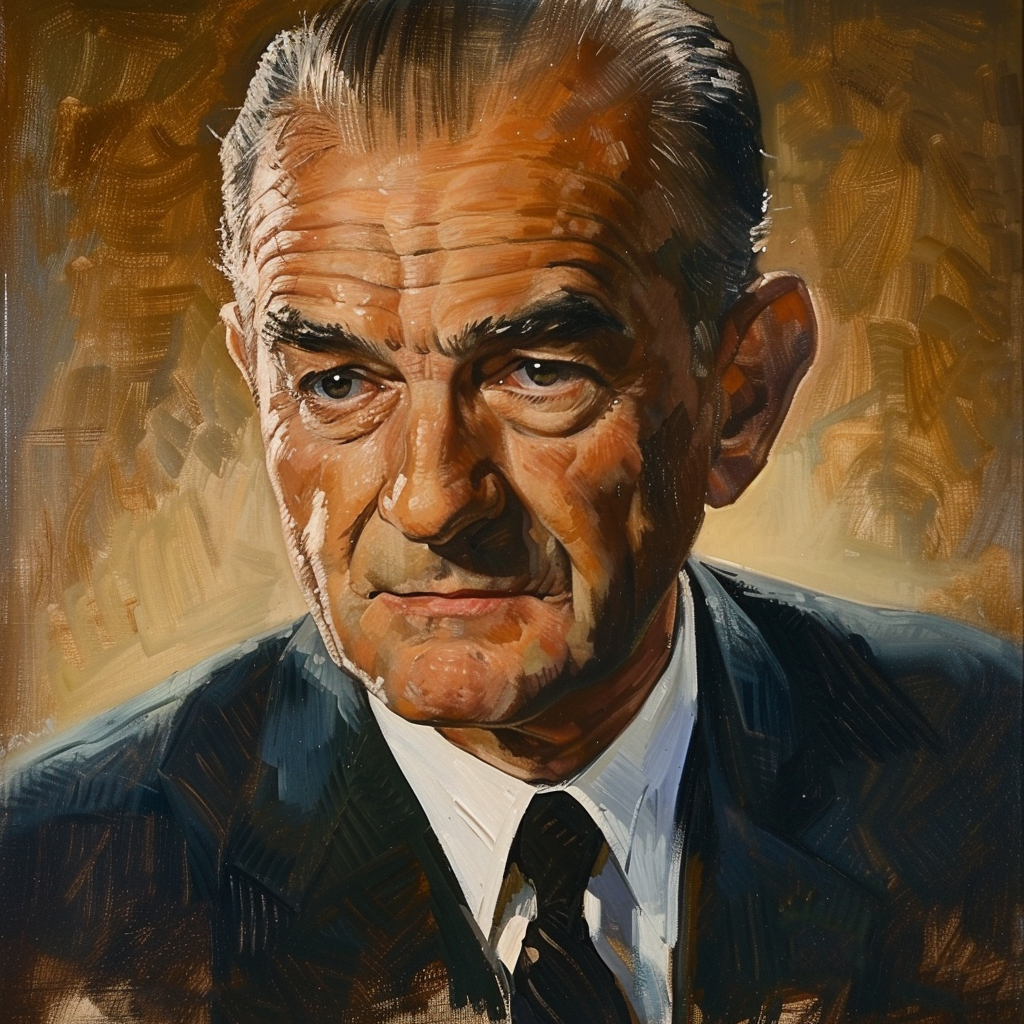

![By Arnold Newman, White House Press Office (WHPO) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons Lyndon Baines Johnson, 36th President of the United States](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c3/37_Lyndon_Johnson_3x4.jpg/256px-37_Lyndon_Johnson_3x4.jpg) Lyndon B. Johnson summary: Lyndon Johnson, also often referred to as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States of America. He was born in Texas in 1908. After attending what is now Texas State University, Johnson taught school for a short period of time. He was more interested in politics than teaching, and in 1931, he became a legislative secretary under a Texas congressman. He was elected by a special election into Congress in 1937, and then he served several terms through 1948. He was elected into the senate in 1948 and became minority leader in 1953—the youngest in the history of the US Senate. The following year, when the Democrats took control of the senate, he became the majority leader.

Lyndon B. Johnson summary: Lyndon Johnson, also often referred to as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States of America. He was born in Texas in 1908. After attending what is now Texas State University, Johnson taught school for a short period of time. He was more interested in politics than teaching, and in 1931, he became a legislative secretary under a Texas congressman. He was elected by a special election into Congress in 1937, and then he served several terms through 1948. He was elected into the senate in 1948 and became minority leader in 1953—the youngest in the history of the US Senate. The following year, when the Democrats took control of the senate, he became the majority leader.

In 1960, he was chosen by John F. Kennedy to be Kennedy’s vice-president on the Democratic ticket. Kennedy defeated Richard Nixon, who was vice-president under Republican incumbent Dwight Eisenhower, by a small margin. In 1963, Kennedy was assassinated, and Johnson became the 36th U.S. president. This marked his serving in all four of the federal offices that were held by election. Johnson defeated Barry Goldwater in the 1964 presidential election by 61 percent of the popular vote.

During his presidency, his agenda for Congress was to pass his "Great Society" programs, wide-ranging initiatives on health and health care, education, conservation, urban renewal, etc. The Medicare and Medicaid programs were initiated. He was known for supporting civil rights and public broadcasting. The Voting Rights act was passed during his presidency, as was the Civil Rights Act of 1968. Under his administration the U.S. space program continued its pursuit of the challenge President Kennedy had laid down to place an American on the moon before the end of the 1960s, a goal that was realized on July 20, 1969, a few months after Johnson left office. However, his inability to end the conflict in Vietnam cast a pallor on his term and led to widespread anti-war demonstrations, and he chose not to run for re-election in 1968. Lyndon Johnson died in 1973.

Articles Featuring Lyndon B. Johnson From History Net Magazines

Featured Article

President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Vietnam War Disengagement Strategy

More than thirty-five years past the 1968 Tet Offensive provides an excellent vantage point from which to re-examine the alleged truths about the Vietnam War. One such ‘truth’ is that President Lyndon Baines Johnson, in sending U.S. Marines ashore in March 1965, followed shortly thereafter by U.S. Army ground combat units, broke the strategic continuity of American involvement in Vietnam and, in so doing, paved the way for the U.S. forces’ ultimate defeat.

But that theory cannot withstand dispassionate analysis. The American commitment to Vietnam was very much part of the overall U.S. Cold War strategy. As President Harry S. Truman said on June 27, 1950, at the beginning of the Korean War, the attack on Korea made it ‘plain beyond all doubt that communism has passed beyond the use of subversion to conquer independent nations and will now use armed invasion and war.’ Containment of such Communist expansion in Southeast Asia would remain the bedrock of U.S. national and military policy for the next 25 years.

The Eisenhower administration approached nation building in South Vietnam in the classic terms of Cold War confrontation. An international alliance — the South East Asia Treaty Organization in the case of South Vietnam — was supposed to deter Communist forces from conventional aggression by threatening belligerent Communist regimes with conventional warfare, backed by a possible nuclear strike by the United States if the fighting got out of hand. Then American money would prime the pump of economic development and ameliorate dire social conditions in the nations under Communist attack. American advisers would work with local governments and military units. In theory, successful nation building would defeat the Communists and forestall any American involvement in a conventional ground war.

American policy toward an independent South Vietnam first took shape in the late summer and early fall of 1954, after the Geneva Conference armistice agreement between French Union forces and Ho Chi Minh’s government created two states, North and South Vietnam. In a letter to South Vietnam’s new leader, Ngo Dinh Diem, dated October 1, 1954, President Dwight D. Eisenhower explained the rationale for his support of South Vietnam: ‘The purpose of this offer is to assist the Government of Vietnam in developing and maintaining a strong, viable state, capable of resisting attempted subversion or aggression through military means … . Such a government would, I hope, be so responsive to the nationalist aspirations of its people, so enlightened in purpose and effective in performance, that it will be respected both at home and abroad and discourage any who might wish to impose a foreign ideology on your free people.’

The Kennedy administration sustained and even intensified this strategic approach to containment of Communist expansion in Vietnam. President John F. Kennedy responded belatedly to Hanoi’s 1959 decision to subvert South Vietnam by increasing the size and scope of American financial and advisory assistance to the South Vietnamese. But Kennedy and his advisers remained well within the conceptual limits of classic nation-building theory: America’s role was to provide South Vietnam with supplementary skills and resources to accelerate indigenous economic development, political mobilization by state structures and military self-reliance.

National Security Action Memorandum 52, issued on May 11, 1961, set forth the Kennedy administration’s policy for South Vietnam, essentially affirming the previous Eisenhower policy. It stated, ‘The U.S. objective and concept of operations stated in the report are approved: to prevent communist domination of South Vietnam; to create in that country a viable and increasingly democratic society, and to initiate, on an accelerated basis, a series of mutually supporting actions of a military, political, economic, psychological and covert character designed to achieve this objective.’

Later, President Richard M. Nixon’s program of ‘Vietnamization,’ under which American forces withdrew and the South Vietnamese increased their own war-fighting capacity, again invoked the theme of nation building, but only after many Americans had lost confidence in South Vietnam’s capacity to prevail in the long run against Hanoi.

In between the Eisenhower administration’s programs and Nixon’s Vietnamization effort, an apparent aberration in American strategy occurred. Beginning in March 1965 — at the request of General William C. Westmoreland, the MACV commander — President Johnson committed to South Vietnam an American field army of two Marine and seven Regular Army divisions with appropriate logistic, air and naval support. Many analysts have been misled by this 1965 escalation of military force into concluding that it represented a change of U.S. strategy in Vietnam. Controversy then grew around the wisdom of this imputed innovation in America’s Cold War policy. This new strategy was said to have resulted in South Vietnam’s defeat at Communist hands.

But LBJ’s 1965 decision to escalate the force deployed in Vietnam did not signal a discontinuity in strategy, nor did it represent an Americanization of the war so that an acceptable victory over Hanoi could be obtained unilaterally by American arms. LBJ’s escalation of direct American participation in the war was a response to a prior escalation by Hanoi in 1964, in which North Vietnamese regular forces had been committed to battle in South Vietnam. Faced with the potential defeat of South Vietnam’s volunteer armed forces, Johnson authorized General Westmoreland to fight a limited war with American and allied combat units. Westmoreland was instructed to prevent the fall of South Vietnam as an independent nation-state governed by its own people and to secure its borders against further North Vietnamese incursions.

In April 1965, when he acted on recommendations to use American air power against North Vietnam, President Johnson reiterated his reasons for that decision and for subsequent escalation of the war. In an address at Johns Hopkins University, he said: ‘Our objective is the independence of South Vietnam and its freedom from attack. We want nothing for ourselves — only that the people of South Vietnam be allowed to guide their own country in their own way. We will do everything necessary to reach that objective, and we will do only what is absolutely necessary.’

Johnson’s strategic objective in South Vietnam, as articulated at Johns Hopkins, was the same one set forth previously by Kennedy in National Security Action Memorandum 52. In his April 1965 speech, Johnson limited himself to a defensive strategy of containment in Indochina. His limited goal was to keep North Vietnam from destroying South Vietnam’s capacity for self-defense, preserving its ‘independence and freedom from attack.’ Johnson never meant for American forces to win the Vietnam War by taking offensive action in the traditional sense. American soldiers were merely intended to act as guardians at the gate until the South Vietnamese could reconstitute their armed forces consistent with their collective national resolve.

Two decisions made by Johnson in 1967 offer compelling evidence for interpreting his controversial escalation of the American role in the Vietnam War as a temporary expedient rather than as a new strategy for victory. First, he sent Ellsworth Bunker to South Vietnam as the new ambassador with private instructions to prepare for the disengagement of American forces. Second, that summer he denied Westmoreland’s request for substantial augmentation of American combat forces for tactical use against Communist base areas inside South Vietnam.

Johnson gave his instructions to Bunker in a private meeting between the two men. Both have since died, but Bunker once related to me his recollections of that meeting and told me how his subsequent decisions as the senior American official in South Vietnam had been shaped by Johnson’s directive to disengage American forces from Vietnam. After the war ended, I interviewed Bunker at his Vermont farmhouse about his experiences as American ambassador in South Vietnam from 1967 to 1973. I asked him, ‘By the way, why did Lyndon select you to go to Saigon?’

‘That’s easy,’ Bunker replied. ‘Because of the Dominican Republic. I had gotten him out of the Dominican Republic and still accomplished his political objectives there.’

In the spring of 1965, Johnson had sent 25,000 American troops to the Dominican Republic to prevent pro-Castro elements from coming to power in the civil war that was about to start between right- and left-wing armed Dominican units. Johnson had found it easy to send in American troops, but then his diplomats had had trouble arranging a political solution to the rivalries that had brought the country to the edge of chaos. Bunker found the negotiated solution Johnson desired, and the American troops came home.

The call for Bunker to go to Saigon had come suddenly and unexpectedly. En route home from a conference in Buenos Aires, he had received a message that Secretary of State Dean Rusk wanted to see him. Rusk told Bunker: ‘The president is in Texas and wants to see you Tuesday morning on his return. But I forewarn you that he wants you to go to Vietnam.’ As scheduled, Bunker saw President Johnson alone in the Oval Office. The president quickly came to the point — ‘I want you to go to Vietnam,’ he said. ‘It’s the most important problem facing the country today, and I need you there.’

LBJ avoided specifics and focused on the mission he wanted Bunker to accomplish in South Vietnam. Johnson wanted to begin withdrawing American forces. To de-escalate without losing the struggle demanded that the expansion and training of the South Vietnamese army be accelerated so that it could take over more and more combat responsibilities. As the South Vietnamese capability increased, Johnson believed the United States could withdraw units without risk of defeat. Simultaneously, LBJ wanted the South Vietnamese to accelerate the development of a participatory political structure, which would make the people completely responsible for their nation’s destiny.

Much has been written of Johnson’s decisions regarding the Vietnam War, much of it by commentators predisposed to criticize LBJ for one reason or another. Today it is generally believed that Johnson was bent on escalation and full-scale war, whereas Kennedy had been essentially a man of peace, seeking withdrawal from a military confrontation over the future of South Vietnam. According to this unflattering stereotype of LBJ, only in March of 1968 — after the Tet Offensive — was he finally dissuaded from a policy of escalation. It also has been said that, in a reassessment of the war precipitated by that Communist offensive, Secretary of Defense Clark Clifford and other ‘wise men’ prevailed on Johnson to abandon war for peace.

Contrary to that prevailing wisdom, Bunker said that by early 1967 President Johnson was already seeking a formula for de-escalation and eventual disengagement of American forces from Vietnam. Why he did not make such plans part of his public discussion of the war, only he knew. Today, with both Bunker and LBJ gone, I can do no more to verify what Bunker told me about President Johnson’s decisions than report his recollections of their conversation and demonstrate that every subsequent action taken by both men was consistent with those 1967 instructions.

From the start of his service as ambassador in Saigon in 1967, Bunker set his mind on four goals. First, South Vietnam’s leadership had to be convinced that it was necessary to build a legitimate government reflecting the country’s political forces. Second, a successful pacification program should create a civil order of legal process in the rural areas, removing politically motivated armed violence from the lives of the ordinary people. Third, the South Vietnamese army must take over from American combat forces the task of keeping the large Communist fighting units at bay. And fourth, the South Vietnamese government had to promote economic development to improve living conditions for its people and finance the continued struggle against the North.

Bunker encountered no opposition to the policy of withdrawal from General Westmoreland. Westmoreland had accepted the new policies set in motion at the Guam conference in April 1967 regarding constitutional reform, presidential elections, rural pacification and upgrading South Vietnam’s armed forces.

Westmoreland’s strategic posture in 1967 incorporated his prior understanding of American objectives to defend South Vietnam from outside attack. His famous 44-battalion request of June 1965 had been made not strategically — to change the fundamental parameters of American policy — but tactically, to confront an immediate threat of North Vietnamese escalation. As his 1965 concept of operations made clear, American units would not be introduced into combat to assume responsibility for a strategic offensive against Hanoi. Rather, they would, in three phases, blunt the enemy’s conventional attack, then clean out major Communist base and staging areas within South Vietnam and finally push Communist units out to South Vietnam’s borders with Laos and Cambodia. Once those tasks were accomplished, as Westmoreland had implied in 1965, South Vietnamese forces would again carry the brunt of any continued combat with the Communists, and American combat units could disengage.

Westmoreland’s ‘Commander’s Estimate of the Situation,’ submitted on March 26, 1965, had defined the American objectives in South Vietnam as ‘A. Cause the DRV [Democratic Republic of Vietnam] to cease its political and military support of the VC in SVN [South Vietnam]’ and ‘B. Enable an anti-Communist GVN [government of Vietnam] to survive so that ultimately it may defeat the VC insurgency inside SVN.’ Westmoreland developed his assessment of the war’s future evolution into a three-phase concept of operations. Phase I would employ the initial reinforcements to prevent the loss of South Vietnam and halt the losing trend by the end of 1965. Phase II would employ additional U.S. and allied forces during the first half of 1966 to destroy enemy forces operating in high priority areas of South Vietnam. Phase III would require all allied forces to work in tandem to deny the enemy use of base areas within South Vietnam and to destroy all enemy forces capable of massing within the country. In mid-1965, Westmoreland expected Phase III to be completed by the end of 1967 — at which point American allied forces could begin to withdraw from South Vietnam as that country’s government became able to establish and maintain internal order and to defend its borders.

Bunker’s arrival in South Vietnam coincided with military operations leading up to Phase III of Westmoreland’s original war plan. Under those circumstances, it was not hard for Bunker to work with Westmoreland in planning for the next phase — as yet unannounced — when American troops would begin to withdraw. In his spring 1967 force augmentation requests to President Johnson, General Westmoreland indicated that American forces could be withdrawn when Hanoi’s aggressive capabilities inside South Vietnam had been permanently nullified.

Speaking at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., in November 1967, Westmoreland laid before the public his concept of withdrawal-as-victory. Few took notice of his prescription at the time. Westmoreland further predicted that American forces would begin to withdraw from South Vietnam in 1969, as in fact they did.

Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara had visited Saigon in July 1967. Seeking to improve South Vietnam’s military might, General Westmoreland presented a series of proposals to strengthen Saigon’s regular forces and improve South Vietnam’s less well-equipped provincial guards and village militia. Quarterly reviews would be instituted to measure progress against planned objectives and to ensure that course corrections were made as needed. Westmoreland would involve the South Vietnamese Joint General Staff in preparation of the combined campaign plan for 1968, which set forth specific goals for each military unit engaged in the war. The proposals were the first results of Bunker’s effort to turn the war over to the South Vietnamese.

Secretary of Defense McNamara stood behind those proposals. He told the South Vietnamese leaders that their future would be better secured over the long run by improvements in the performance of their forces in combat than by reliance on American fighting power.

McNamara delivered more significant news to Ambassador Bunker and General Westmoreland: American Reserve units would not be called into service to fight the Vietnam War. The limits of American involvement had clearly been reached, and President Johnson had decided to authorize only a modest increase in American forces deployed in South Vietnam. Westmoreland’s requests for significant force augmentation were denied. President Johnson wanted no further escalation. On August 3, 1967, the American force ceiling was officially raised to 525,000 men, less than General Westmoreland’s minimum request of the previous spring. This little-noticed presidential decision is perhaps the best evidence on record that Johnson had been quite serious about finding a way out of the war without using more American forces.

Johnson’s decision during the summer of 1967 to limit American participation in fighting against Hanoi effectively prevented the United States from achieving a conventional victory in the Vietnam War. The president’s decision not to give Westmoreland enough troops to more quickly grind up Hanoi’s regulars and clean out enemy base areas inside South Vietnam increased Americans’ frustration with the conflict. But both of those decisions were consistent with the strategic direction President Johnson had earlier given to Ambassador Bunker. America’s victory or defeat in the war would be determined by the South Vietnamese.

President Johnson’s unwillingness to commit additional troops to the war was welcomed by Hanoi’s senior strategist, Vo Nguyen Giap. He believed that Hanoi’s strategy of attrition was clearly beginning to achieve results. During the summer of 1967, Giap wrote an article published in English as ‘The Big Victory, the Great Task,’ wherein he presciently concluded: ‘At present, the United States does not have enough troops to meet Westmoreland’s requirements … . America’s economic and military resources, although great, are not boundless.’ Giap then set in motion preparations for the massive offensive scheduled to take place during the Tet holiday in early 1968.

Perhaps the most appropriate way for observers and historians to phrase the basic inquiry about Vietnam is not ‘Did America’s strategy work?’ but rather ‘Was American confidence in the South Vietnamese well-placed?’ The proper question stresses nation building more than conventional war-fighting techniques. If the second question is the more relevant, then responsibility for the war’s outcome rested with America’s civilian political leadership, which alone had to judge whether or not to lend support to an allied nation.

Even a cursory survey of the record indicates that American military operations were successful in achieving the limited nation-building goals established by policymakers. In 1972, an invasion force of 22 North Vietnamese divisions was defeated on South Vietnamese battlefields through the combined application of American air power and South Vietnamese ground operations. Guerrilla forces supporting the Communist effort within South Vietnam had by then collapsed, and the South Vietnamese population had been mobilized in every village, town and city to support an elected government in Saigon. American forces withdrew from South Vietnam when North Vietnam had yet to win the war. North Vietnam’s attack against South Vietnam did not succeed until some time after the withdrawal of U.S. troops.

As Johnson’s personal representative, Bunker went to Saigon in 1967 and began the process that led to a systematic phase-out and withdrawal of American combat forces. When Bunker left the country in May 1973, all American combat forces had long since been withdrawn. South Vietnam was defending itself and could boast an economy showing resilience in the midst of war. And the Vietnamese Communists had signed a peace treaty pledging to respect South Vietnam’s autonomy and independence. Where his predecessors as ambassador had encountered frustration and failure, Bunker had succeeded. He had been a superb choice.

The article was written by Stephen B. Young and originally published in the February 1998 issue of Vietnam Magazine.

For more great articles be sure to subscribe to Vietnam Magazine today!