Republic’s P-47 wasn’t a sexy or groundbreaking fighter but it possessed one essential quality prized by pilots: It got the job done and returned them safely home.

World War II saw three U.S. Army Air Forces fighters of consequence: everybody’s favorite, the North American P-51; the remarkable Lockheed P-38; and the absurdly large Republic P-47. Curtiss P-40s made meaningful contributions as well, but the big three owned the skies—the Lightning over the Pacific, the Mustang and Thunderbolt sharing the European theater. The P-40 bore the brunt of North African combat but turned out to be overmatched by Messerschmitt Me-109s and their experienced Luftwaffe pilots.

The P-47 Thunderbolt was the AAF’s most conventional WWII fighter. Other than the fact that it had a turbocharger, it was an evolutionary design like the P-40, with its antecedents in the 1930s. Yet it was built in greater quantities—15,683 units—than any other U.S. fighter.

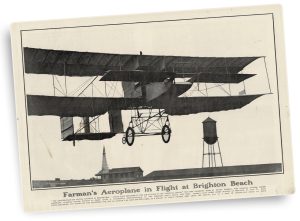

In some respects, the P-47 dated back to 1931 and the earliest days of Alexander de Seversky’s struggling Seversky Aircraft Company—a firm that in 1939 would be renamed Republic. Was the Thunderbolt a Republic design, or did it owe much to the 1930s airplanes created by Russian émigré, air power advocate and entrepreneur de Seversky? The popular position is that Republic engineer Alexander Kartveli designed the P-47 on the back of the proverbial envelope during an overnight train trip to Wright Field in Dayton, Ohio. The most convincing proponent of de Seversky’s crucial role in the design was the late engineer and aviation historian Warren M. Bodie, whose book Republic’s P-47 Thunderbolt: From Seversky to Victory claims that de Seversky never got the credit he deserved.

Bodie argued that de Seversky was marginalized because of his difficult personality and lack of business acumen. Politics were said to have played a major role in the Air Corps’ focus on the Allison V12 engine, and well-connected Curtiss and its fighter proposals had more War Department juice than did de Seversky’s radial-engine contributions.

Nobody will ever resolve that dispute, since the principals are long gone and company records of the time have been lost. So we will climb right up onto the fence and say that the Thunderbolt was the creation of not one architect but of several, the most important of them being de Seversky and Kartveli.

The P-47’s remotely mounted turbocharger lived in the aft fuselage, with a thicket of ductwork that fed engine exhaust and intake air to the turbo. Some of the air scooped up by the P-47’s big horse-collar cowling also passed through an intercooler that removed heat from the air compressed by the blower. The turbocharger and its unusual location was a de Seversky concept.

So was the P-47’s thin, semi-elliptical, high-speed wing and airfoil, which first appeared on de Seversky’s 1931 SEV-3 amphibian. Most sources say the wing was designed by de Seversky and his chief engineer at the time, Michael Gregor. Kartveli claimed that he designed the wing when he was Gregor’s assistant.

De Seversky and Kartveli, who had become the Seversky Company’s chief engineer, turned their all-purpose, radial-engine airframe into a basic trainer, the BT-8. Then it became a fighter, the Seversky P-35, which would become the XP-41 and ultimately the Republic P-43 Lancer.

Air Corps leaders had seen that the British and Europeans were focusing on liquid-cooled V12 engines for fighters. They became proponents of the Allison V-1710 V12, though de Seversky called it a “junk engine.” Most of the Army’s Allison-engine fighters—the P-39, P-40 and the original Mustang, the P-51A—were obsolescent by the time they went into service. Allisons, all with single-stage superchargers, were only successful in the P-38 Lightning, and only because they were turbocharged. In fact, Allison had intended all along that the V-1710 be turbo-blown. But this was a job traditionally left to the airframe manufacturers. None but Lockheed and Republic could find space in their fighters for a big exhaust-driven blower.

De Seversky and Kartveli had modified the original SEV-3 amphibian airframe in a variety of ways—subtracting seats, changing canopies, modifying the fuselage and trying more-powerful engines—but one characteristic that remained was the deep cabin with room for a third passenger in what was otherwise used as a baggage compartment. When de Seversky created the P-43, this gave him the space, aft of the wing trailing edge, to fit a General Electric turbocharger originally developed for the B-17. It was the first radial-engine fighter in the world to have a turbo.

The P-43 was the end of de Seversky’s contributions to development of the P-47. A palace revolution in 1939 saw him booted out of his own company. Alexander Kartveli would become the vice president of engineering at renamed Republic.

Kartveli’s original XP-47 proposal was no Thunderbolt. Following the lead of General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, Air Corps planners were relying on the concept of a swarm of lightweight, Allison-powered interceptors to counter the threat of bombers attacking America’s shores. That no such threat existed didn’t seem to concern them, so Kartveli and his staff were tasked with designing the smallest and lightest airframe that could be wrapped around a V12. Had it been built, the XP-47 would have been a 4,600-pound midget with two .50-caliber guns and a shrunken version of the Seversky-Gregor SEV-3 wing but no turbocharger.

We can thank the Navy that the XP-47 was replaced by the vastly more significant XP-47B. While the Air Corps worshipped at the Allison altar, the BuAer was pushing Pratt & Whitney to develop an air-cooled super-radial. That engine became the 2,000-hp R-2800, along with the Merlin one of the two most important Allied engines of the war. Though Kartveli was initially opposed to the idea of a remote-mounted turbo, Republic set out to design an airplane around the R-2800 plus the P-43’s turbocharger and its associated ducting. The result was the XP-47B, a six-ton monster with six and then eight .50-caliber guns.

Finally, there was a Thunderbolt. It got the nickname “Jug.” Some say it is short for juggernaut, but a far more likely explanation is that it is a reference to the Thunderbolt’s portly fuselage, back in the days when milk came in glass jugs.

The Army still viewed the Thunderbolt as a defensive weapon, an interceptor, so it wasn’t concerned that there was no room in its wings for fuel. Eight big .50s and their substantial ammunition boxes plus the retracted main gear meant the gas tanks all had to go into the fuselage. Three hundred and five gallons to feed a 100-gallon-per-hour R-2800 gave the Thunderbolt a combat radius of just 165 miles. (Combat radius is how far an airplane can fly and then fight for 20 minutes, before returning to base with enough fuel left to land with a 30-minute reserve.)

The first operational Thunderbolts—P-47Bs of the 56th Pursuit Group, eventually to become the 56th Fighter Group, “Hub” Zemke’s notorious Wolfpack—were assigned the job of protecting the Republic and Grumman factories on Long Island and other aviation facilities in the Northeast. They were based at fields in New York and Connecticut, so at least the domestic Thunderbolts didn’t have far to fly.

The 56th was responsible for an early P-47 myth. In November 1942, two of its pilots were doing high-speed runs at 30,000 feet and put their noses down to descend to 20,000 before repeating the exercise. Thanks to the T-bolt’s massive bulk and clean aerodynamic lines, they dove like dropped safes, and the two lieutenants were the first P-47 pilots to experience compressibility. (Lockheed had encountered it with P-38s a year and a half earlier.) Their airplanes tucked under as shock waves moved the center of lift aft, and the controls froze. The pilots both swore that they saw indicated airspeeds of 725 mph, equivalent to Mach 1.2, before they were able to pull out. They had broken the sound barrier, and Republic’s PR department trumpeted the news.

They needn’t have bothered, since the fighters never exceeded Mach .83. Years ago, Curtiss-Wright test pilot Herb Fisher explained to me why the lieutenants’ story was true as far as it went but had nothing to do with breaking the sound barrier. Fisher had done plenty of P-47 dives while testing its huge Curtiss Electric prop, so he knew that propellers have a built-in speed limit no matter how much power you feed into them. At about 560 mph true airspeed, or Mach .83, a propeller can’t be pushed any faster through the air, for at that point there is a monumental rise in drag.

So why did those pilots see an indicated 725 mph? Because the ambient air that filled their airplanes’ pitot-static systems at 30,000 feet couldn’t vent fast enough during an extreme dive to produce accurate airspeed readings.

Republic had introduced the P-47 with the boast that it was the fastest fighter in the world, which was true (at altitude). The highest speed Republic ever recorded was 504 mph, with a P-47J at 34,450 feet. The best the AAF could do was 484, so they doubted Republic’s claim. But any such boast was met with bafflement, considering the airplane’s size. Photos of P-47s sitting on ramps with helmetless technicians or engineers in the cockpit look for all the world as though a 6-year-old has snuck into the seat at an airshow. Even Kartveli reportedly said, “Nice airplane, but it is too big.”

Claims about P-47 performance characteristics varied widely. A few fighter groups, notably Zemke’s Wolfpack, loved their Thunderbolts, but most preferred Mustangs. Some of the most extreme claims can be traced back to the book Thunderbolt!, by 56th Fighter Group 27-victory ace Robert S. Johnson and the late aviation author Martin Caidin. An experienced civilian pilot and hugely colorful writer, Caidin never let reality get in the way of hyperbole, and some of Johnson’s P-47 opinions in the book were almost certainly enlarged by Caidin’s lens.

Johnson claimed the Thunderbolt boasted a faster roll rate than any other U.S. fighter and had superb turning performance. It in fact possessed an average rate of roll and poor turning talent. “The P-47 was too heavy for some maneuvers,” said one Luftwaffe pilot. “We would see it coming from behind and pull up fast, and the P-47 couldn’t follow, and we came around and got on its tail.” And though the Thunderbolt went downhill like an express elevator, its climb rate was lousy. “It ought to be able to dive,” said P-51 fan and ace Don Blakeslee. “It certainly can’t climb.”

In 1944 Hamilton Standard paddle-blade propellers were fitted to P-47s, replacing the narrow-blade props that Thunderbolts had carried until then. Caidin’s book has Johnson saying that the new wide-blade props “added 1,000 horsepower” and provided spectacular climb performance. In truth, the new props increased the rate of climb from miserable to acceptable.

In October 1944, examples of all the military’s production fighters were gathered at the Navy’s test facility at Patuxent River, Md., and were flown and assessed by a number of experienced combat pilots during the Joint Fighter Conference. The results, and many other P-47 facts and numbers, appear in Francis H. Dean’s splendid doorstop of a book, America’s Hundred Thousand. A sampling:

The P-47 had a drag coefficient of .0217, second only to the P-51D’s and P-63A Kingcobra’s .0176.

The Thunderbolt’s guns threw 12.72 pounds of lead per second, while all other fighters delivered between 9.26 and 9.54 lbs./sec.

P-47 combat losses were exceptionally low: less than 0.7 percent of all the Thunderbolts made.

The Joint Fighter Conference pilots judged P-47 maneuverability to be from fair to poor, though it did fly best at high altitudes. Roll rate was middling—about 4.2 seconds for a full roll. The P-47D’s turning performance was worse than that of any fighter but the F4U Corsair.

The P-47D was a ground-lover, requiring a 2,450-foot takeoff roll—worse even than the 17,000-pounds-heavier, twin-engine P-61 Black Widow.

Despite its fabled diving ability, the P-47D finished behind the P-38G, P-51D and F4U-1D in the dive tests.

As with most aircraft installations, the P-47’s turbocharger didn’t act like the turbos on Porsches and Subarus, which greatly increase a sports or race car’s power. A P-47 turbo didn’t “make power,” it simply maintained the engine’s rated power regardless of altitude, which is called turbo-normalizing. At sea level, a Thunderbolt’s R-2800 engine put out 2,000 hp at full throttle (2,100 hp on later models). At 30,000 feet, it could still make 2,000 hp, thanks to the turbo converting thin atmospheric air into thick intake air.

The exception was a throttle setting called war emergency power, which lived within the last eighth inch of a P-47’s throttle travel. When this Pandora’s box was opened, 2,535 hp (2,800 hp on later engines with improved turbos) could be drawn from the engine. But only for five minutes and with water injection to tamp down the detonation that would otherwise quickly have melted the pistons.

The first P-47s began operating from England in March 1943, initiating the struggle to lengthen the Thunderbolt’s legs. Kartveli initially resisted demands that shackles and pylons for drop tanks be allowed to mar the clean lines of his airplane. He called them “ornaments.” The original range-extending tank was a 200-gallon conformal centerline belly bulge (eventually expanded to a 300-gallon monstrosity) that not surprisingly was called the Tumor.

A variety of drop-tank shapes and sizes found their way onto P-47s, but most typical was a pair of 108-gallon aluminum or paper tanks. Yes, paper. The British had developed tanks made of layers of molded and pressed paper, and they were quickly adopted by P-47 units. The tanks were good for just one mission before the fuel began to delaminate them, but they offered the added advantage of providing no scrap metal for an aluminum-hungry enemy when they were pickled.

Ultimately, Thunderbolts could be fitted with enough centerline and underwings tanks to escort bombers almost to their most distant targets—a vast improvement over P-47s that could barely make it 75 miles into France before turning back to England.

P-47s never figured prominently in the Pacific War. It was largely fought by Navy fighters and Army P-38s, which had the range that the Thunderbolt lacked. The exception was the China-Burma-India Theater, where the P-47’s rugged durability at the end of a long supply chain stood it in good stead. But much Pacific air combat was done at low and mid altitudes, against agile A6M Zeros and Ki-43 Oscars, and the lower a P-47 flew, the more its truck-like qualities became apparent.

The fact that Johnson, Zemke, Francis Gabreski and David Schilling—the highest-scoring aces in the European theater—all flew Thunderbolts has been offered as evidence of the airplane’s superiority. But it’s really just evidence that the P-47 got into the fight early, well before the Mustang did, and fought in a target-rich environment. Overall, the leading American ace producers were the F6F Hellcat, the P-51 and the P-38. And again, it’s a matter of context: Late in the war, Hellcats were attacking Japanese schoolboys flying worn-out Mitsubishis and Nakajimas.

When the AAF threatened to shut down P-47 production in 1944 because of the airplane’s limited range, Kartveli and his team created the long-winged P-47N, for use as a B-29 escort in the Pacific. An 18-inch extension of each wing at the root allowed tankage for another 93 gallons, raising total internal fuel to 556 gallons. With full internal and drop-tank fuel (1,266 gallons, for a maximum range of 2,350 miles), a P-47N took off weighing more than 10 tons, at the time a record for single-seat, piston-engine fighters. The P-47 remained in production until the end of December 1945—longer than any other WWII Army fighter.

Yet the P-47’s fame came not from escort duty, which was soon taken over by longer-ranging P-51Ds, but from the T-bolt’s utility as a ground-attack fighter-bomber. In March 1944, P-47s began flying low-level bombing and strafing missions. Their eight guns made for a potent broadside. Thunderbolts could also carry unguided rockets in underwing launch tubes. Though each rocket had the impact of a 105mm round, they were hard to aim accurately and were only effective against large targets.

D-Day planners quickly realized that Thunderbolts would be the perfect weapons with which to attack Wehrmacht relief columns, advancing armor, rail supply lines, bridges and other means to throw back the Allied invasion. The Normandy campaign, Operation Market-Garden and the Battle of the Bulge were the P-47’s major ground-pounding operations.

Strafing was more dangerous than aerial combat. A strafer was usually in danger from ground weapons ranging from Lugers to 88s throughout an attack run, and even a single rifle bullet could cripple a system or kill a pilot. P-47s were the least vulnerable of the Allied fighter-bombers, for they had no liquid-cooling plumbing or radiators that might be disastrously holed. In fact, the big Pratt radial was a 2,400-pound steel-and-aluminum shield against frontal fire.

Despite its faults, the P-47 excelled at the two extremes of its performance envelope—as a speed-merchant bomber escort at 30,000 feet and as a juggernaut fighter-bomber at 50 feet. Thunderbolts shot down more Luftwaffe aircraft—3,572—than any other Allied fighter, and they disposed of 170,000 locomotives, railcars, armored vehicles and trucks.

The P-51 got the glory, but the P-47 did the grunt work.

Contributing editor Stephan Wilkinson recommends for further reading: Republic’s P-47 Thunderbolt: From Seversky to Victory, by Warren M. Bodie, and Thunderbolt: A Documentary History of the Republic P-47, by Roger A. Freeman.

This feature originally appeared in the November 2020 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here and don’t miss an issue!