In March 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson, intent on preventing North Vietnam from putting its full military might into an invasion of South Vietnam, authorized Operation Rolling Thunder, a sustained bombing campaign targeting the North’s military infrastructure. The White House established a 10-mile radius around the North Vietnamese capital of Hanoi as off limits to American air power. In addition, a 30-mile radius was put under White House control, so that only President Johnson had the authority to order air operations within that area.

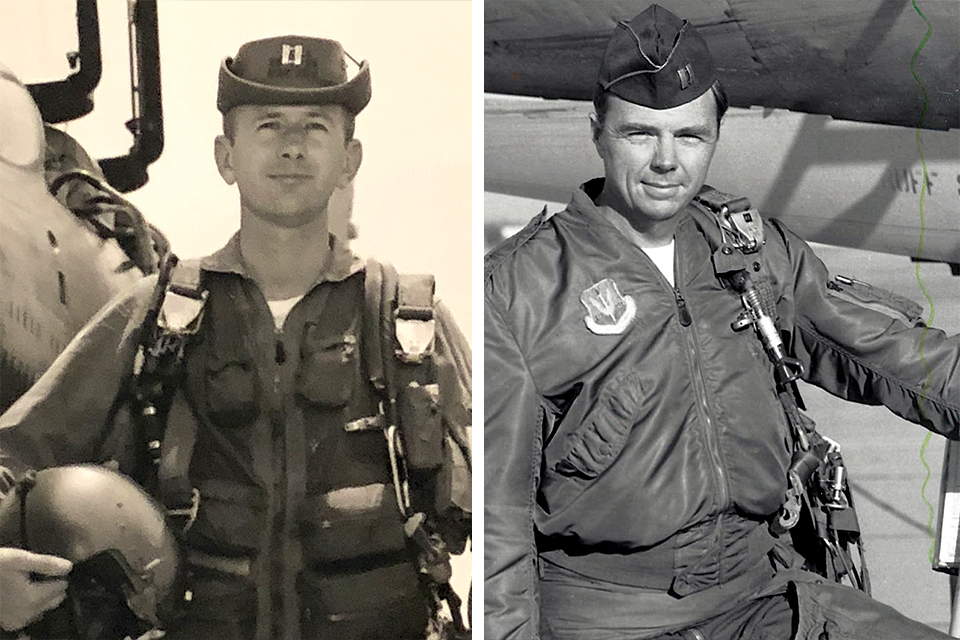

On July 24, 1965, four U.S. Air Force McDonnell F-4C Phantoms took part in an airstrike against the Dien Ben Phu munitions storage depot and the Lang Chi munitions factory west of Hanoi. The Phantoms dropped their ordnance and withdrew to provide MiG suppression for the Republic F-105D Thunderchief fighter-bombers that followed. One of those F-105s was piloted by Captain Victor Vizcarra of the 80th Tactical Fighter Squadron. “As we started climbing out of the area after our single pass at the target, our mission commander informed the Phantoms that we were departing,” Vizcarra recalled. “We all remained on the same frequency as we climbed and headed south. Suddenly we heard a call from the F-4s. ‘What the hell was that?’ one of them said.”

Leopard Lead called for his Phantom flight to check in. Leopards Three and Four responded, but Two was never heard from, having been blotted out of the sky by a surface-to-air missile (SAM). The blast had also damaged the other three Phantoms in the flight. They were the first victims in Vietnam of the soon-to-be-infamous SA-2.

Known to its Soviet builders as the S-75 Dvina, the SA-2 had come as a rude shock to NATO in the early 1960s. Although the United States was aware the Soviet Union had developed an anti-aircraft missile, the SA-2 exploded onto the world stage by shooting down Francis Gary Powers’ Lockheed U-2 spyplane at an altitude of 70,000 feet.

Thirty-five feet long and carrying a 440-pound warhead, the SA-2—launched by a solid-fuel booster and featuring a liquid-fueled second stage—streaked to its target at 2,500 mph. The warhead’s lethal radius was more than 220 feet wide at low altitude and much wider at high altitude, rendering it extremely dangerous to any American plane.

Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara was anxious to avoid escalating the war by provoking Soviet and Chinese involvement. He convinced Johnson that caution was key to keeping the war under control. However, McNamara’s forte was strategy, not tactics, and his advice ignored the grim realities of modern warfare.

While the U.S. proceeded cautiously, the North Vietnamese were determined to use whatever means they had at their disposal to achieve victory. The North recognized and exploited the sanctuary provided by the White House’s overly restrictive rules of engagement. McNamara had convinced Johnson to list certain North Vietnamese targets as off limits, including Soviet ships off-loading cargo in Haiphong Harbor, so the entire seaport could not be attacked.

Incredibly, the list also included SAM batteries.

In April five SAM sites had been discovered under construction within the restricted zone. This was just a month after the initiation of Rolling Thunder, and came as a great shock to the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) in the Pentagon. They were adamant that the sites be destroyed before they could be completed, but McNamara convinced the president to keep them off limits. Three times between May and July, the JCS asked the White House to allow the Air Force and Navy to bomb the sites, but each time they were turned down.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

After the loss of the F-4C on July 24, the Joint Chiefs again urged Johnson to authorize a strike against all known SA-2 positions, which had also been discovered outside the 30-mile exclusion zone. This was no small matter to the pilots flying missions over North Vietnam. Up to that point, F-4 and F-105 fighter-bombers had been able to avoid anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) by flying at altitudes above the range of the Soviet-made ZPU-23 and 37mm guns.

At last the Pentagon prevailed. President Johnson gave the order: “Take them out.” The mission was assigned to tactical fighter squadrons based in Thailand flying the F-105 “Thud,” the fastest nuclear-capable fighter-bomber in the world, able to carry 7 tons of ordnance.

But even as the planning for the mission, code-named Operation Spring High, progressed, the voice of doom in Washington was still trying to prevent escalating the conflict. McNamara’s view was that only the two SAM sites that had actually fired on the Phantoms should be targeted. He contended that the other sites had Russian advisers working with the North Vietnamese Army (NVA), and if they were killed it might incur the wrath of the Soviet Union. Again Johnson gave in.

On the morning of July 27, the pilots of four tactical fighter squadrons awoke to find their mission objectives changed. They would only attack SAM Sites 6 and 7. This required last-minute planning and delayed the mission into the afternoon. “So the prior night’s flight planning went up in smoke, and we were left scrambling at the last-minute requirements,” said Vizcarra.

The 12th and 357th Tactical Fighter squadrons, flying out of Korat Royal Thai Air Force Base, would attack SAM Site 6, while the 80th and 563rd squadrons, out of Takhli, would hit Site 7. Each squadron’s F-105s would be organized in three four-plane flights. The Korat flights were named for trees: Pepper, Willow, Redwood, Cedar, Chestnut and Dogwood. The Takhli flights bore auto names: Healy, Austin, Hudson, Valiant, Rambler and Corvette. In all, 48 F-105s were to participate in the strike, with some targeting the missiles, launchers and command radar vans while others bombed support facilities and barracks. But even this bifurcated mission was limited in scope: None of the Thuds were assigned to attack the anti-aircraft guns protecting the missile sites.

Recommended for you

Moreover, higher headquarters had the F-105s approaching the target in a “fingertip formation,” arranged in a manner that resembled the left hand’s extended fingertips. Lead was the middle finger, while 2 was the index. Planes 3 and 4 were the ring and little fingers. The formation was completely ill-suited for a low-level, high-speed attack on a fixed site protected by AAA.

“When we read it [the mission plan], we couldn’t believe it,” recalled Vizcarra. “What were those guys at headquarters smoking? They had each flight attacking the targets in fingertip formation. What did they think this was, an airshow? One hit could wipe out the whole flight. Four big F-105s flying close together—nothing like making oneself a bigger target.”

The SAM sites were about 450 miles away from the Thailand bases. Both forces would refuel from orbiting KC-135 tankers and head into North Vietnam. The Korat force would approach SAM Site 6 from the south, while the Takhli force would fly southeast down the Red River valley.

Their weapons loads varied. For the Takhli force, each F-105 in the first flight carried two SUU-7/A CBU-2 anti-personnel bomblet dispensers for “soft” targets, while the second and third flights were loaded with four BLU-27 napalm canisters. Timing was critical. Each flight was to be about 150 seconds, or about 20 miles, behind the one preceding it. This would keep the following planes from being hit by exploding ordnance from the previous attack.

Vizcarra was Rambler 2, with Major Art Mearn as Rambler Lead. The time over target for the two SAM sites was identical. “With us approaching from the northwest down the Red River to hit Site 7 and the Korat group’s simultaneous attack on Site 6, less than three miles to the south, the danger of midair collisions was very real,” said Vizcarra. As Rambler 2, he was off Mearn’s right wing, while Captains Jim Hayes (Rambler 3) and Giles Gainer (Rambler 4) were on the left. “Art told me that as soon as we released our bombs he would call that I had the lead and make a hard right turn to avoid the Korat force coming off Site 6,” he recalled.

The prescribed fingertip formation was still a serious concern, so the flight leaders chose to make the target run in a loose, flexible fingertip formation. This spread the F-105s out to minimize the chance of a single hit damaging more than one plane, and gave them some room to maneuver.

What the Thud pilots didn’t know was that the NVA had moved all available anti-aircraft guns close to the SAM sites. The Americans would be flying into one of the most heavily defended targets in North Vietnam.

It was after noon by the time Operation Spring High began. Two aborts from the Korat squadrons reduced the strike force to 46 planes. After refueling they crossed Laos at 17,000 feet, then entered enemy territory and descended to 100 feet. The rolling North Vietnamese countryside echoed with the sound of heavily laden Thunderchiefs roaring overhead at 500 mph.

Approaching the Red River, the Americans saw heavy AAA crisscrossing the valley ahead. They descended below 50 feet to avoid the deadly web of fire, their F-105s churning up rooster tails of mud and spray over the rice paddies. An RB-66 reconnaissance plane monitored the SAM radar emissions, calling “Bluebells are singing” when enemy radar was activated and “Bluebells are silent” when it was temporarily turned off. As the F-105s streaked deeper into enemy territory, NVA early-warning radars tracked them until they were lost in the ground clutter. With the fast-moving Thuds skimming the ground, the NVA gunners were hampered by the high berms surrounding their emplacements. Nonetheless, they unleashed a hail of AAA fire as the Americans bore in, filling the air with a deadly curtain of hot steel.

Captain Marty Case, in Hudson 4, was part of the third flight assigned to Site 7. “We took triple-A fire about 14 miles out,” he said. “We were so low that the gunners couldn’t depress their guns low enough to hit us, so most of it went over us. As we got closer to the SAM site it was just flames and smoke and triple-A going across—it looked like the end of the world to me. I didn’t think any of us could make it through that alive.”

Captain Kile Berg, Hudson 2, was hit during the approach. “The gunners were trying to hit the lead but we were going so fast they hit the number 2,” Case recalled. “Kile made it to the target, but as we were on the escape route, I looked ahead and his entire airplane from the intakes back was a mass of flames. It looked like a meteor with a needle sticking out.”

Berg managed to safely eject but was captured by the NVA. He spent seven years as a POW.

Captain Jack Redmond, in Valiant 4, remembered a close call as they approached the target:“I was on the left, outboard of Valiant 3, watching to my right when all of a sudden these other planes zipped past us at our altitude. We were only about 50 feet up. They were the Korat planes coming off Site 6.” With a combined speed of almost 1,000 knots, the eight planes blew past one another in the blink of an eye.

While the Korat force hammered Site 6, the Takhli force moved in. The first three flights dropped canister bombs and napalm on the site. There was a lull of two minutes before the next flight of four F-105s came in to drop their ordnance. Valiant Lead Major Phil Call, fourth in the attack stream, misjudged his approach and saw that they were aimed not at their target—the enemy support base north of the missile battery—but at the SAM site itself.

The entire area was burning fiercely from the first three attacks. Major Call radioed his flight that they were off target, to which Valiant 2, Captain John Atkinson, responded, “Well don’t make another pass!”

The four pilots released their cluster munitions a few seconds before passing over Site 7. The SUU-7/As dispensed scores of CBU-2 bomblets, each with the explosive force of a large hand grenade. The bomblets dispersed over a wide area, tearing swaths among enemy troops and vehicles. But as Valiant flight passed over the site, Redmond was stunned and angered to see that the SA-2 missiles they had come to destroy were dummies. “They knew we were coming and set up all those triple-A batteries at the site,” he said. “It was a trap.”

Vizcarra’s Rambler flight was the first to hit the support facilities half a mile north of the main site. “I had my eye on Rambler Lead’s starboard wing as we moved into the target area,” he said. “I hardly ever looked ahead, but when I did, I saw two columns of black smoke rising from numerous fires. All across the valley were the triple-A gun positions. The 37mm shells looked like orange golf balls when they came at me. They exploded into black puffs and I saw the black shrapnel spreading out. Art said, ‘Rambler Lead, 3, 2, 1, pickle!’ Then we all released.”

Rambler and Corvette’s F-105s each carried four BLU-27 napalm canisters filled with jellied gasoline. Their effect on the enemy was horrific as huge fireballs erupted into the sky and tons of burning napalm immolated men, vehicles and fuel. In seconds Rambler was clear of the AAA guns but not out of danger. The Korat force, which had a longer lag time between flights, was still coming off their target.

Vizcarra, as ordered by his lead, pulled up into a hard right bank to get out of the area. The others followed.

The NVA’s 23mm and 37mm guns, not targeted by the strike, were lethal at close range. They shot down four F-105s in the target area, and more than half of the remaining Thuds suffered damage from groundfire. Pepper 2, Captain Bill Barthelmas, was hit over Site 6. He managed to reach Thailand, but his controls failed on approach to an emergency field. He collided with Pepper Lead, Major Jack Farr, and both pilots were killed.

On later reflection, Vizcarra considered himself lucky to have survived the mission. Of the 12 flights, five planes in the number 2 position were lost.

“Valiant Lead and 2 were ordered to tank off and return to the target area to cover the search-and-rescue forces,” Redmond said. “I know others were sent back, but Valiant 3 and I were ordered back to base.” One of the downed pilots, Captain Frank Tullo, Dogwood 2, was found and rescued.

After the 40 remaining F-105s landed, the pilots were debriefed. Slowly a hard and cruel truth emerged: Both SAM sites were devoid of missiles and equipment. The NVA had substituted white-painted bundles of bamboo for the SA-2s. More than 130 AAA guns had been assembled in anticipation of an airstrike. Spring High had destroyed two worthless targets for the loss of six planes and five men.

Vizcarra, who wrote of his experiences in his book Thud Pilot, said: “Spring High was a historic mission. It was the first time in history of an attack against a SAM site. If we had known the site was a trap, we would never have sent the force out. We attacked at low level, which was based on exaggerated assumptions of the SAM’s capabilities. I’m not sure we would have done much better even if we had been able to plan the mission without higher headquarters intervention. We had a lot to learn, and you sometimes have to do the wrong thing to know it was wrong.”

Despite the losses suffered by the F-105 squadrons during the operation, the hard-won lessons of Spring High were the genesis of a highly successful campaign against the SAMs in North Vietnam. Brigadier General Kenneth “K.C.” Dempster headed up an Air Staff anti-SAM task force involving the Air Force, Navy and defense contractors to develop countermeasures against the deadly missiles. Radar homing and warning receivers were installed in F-105s in December 1965, alerting pilots to the presence and location of any radar emissions. The Navy’s Shrike missile, which homed in on a SAM site’s radar emissions, was given the highest priority.

In all, 46 recommendations made by the task force were accepted by the Air Force and put into production, resulting in the famous “Wild Weasel” SAM killers. The Weasels were designed from the outset to hunt down and destroy SAM missile batteries, opening the way for airstrikes into enemy territory. The first modified two-seat North American F-100F Super Sabres arrived in Thailand in November 1965, and successfully destroyed a SAM site on December 22.

QRC-160 jamming pods began arriving in theater in September 1966. For the first time, American fighters could self-jam SAM radars and render them ineffective. By then the number of known SA-2 sites had risen to 18, with another 18 suspected sites.

As the Weasels took a toll on the SAM sites, the life expectancy of U.S. airmen rose dramatically. But the hard truth is it took a defeat to make that victory possible.

Frequent contributor Mark Carlson is the author of The Marines’ Lost Squadron: The Odyssey of VMF-422. Recommended reading: Vizcarra’s Thud Pilot; and Thud Ridge, by Jack Broughton.

This feature originally appeared in the November 2018 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here!