The celebrations surrounding the end of World War II had barely ended when the Cold War commenced between the Western Allies and their Soviet former partner. The war’s end also signaled the onset of the atomic age and a corresponding desire among the victorious nations to secure supplies of uranium and other natural resources. With its vast mineral deposits amid largely unexplored territory, Antarctica was considered a promising potential repository of those vital resources. As such, the United States sought to establish a presence in Antarctica and explore the frigid continent using naval and air assets.

On August 26, 1946, chief of U.S. naval operations Admiral Chester Nimitz announced that a massive combined military expedition dubbed Operation Highjump would be launched into Antarctica in December during summer in the Southern Hemisphere. The operation involved 13 ships, more than 4,700 personnel and a variety of aircraft, including newly purchased helicopters. The naval contingent, known as Task Force 68, was commanded by Rear Adm. Richard H. Cruzen and Rear Adm. Richard E. Byrd commanded the scientific and research elements, with six Douglas R4D-5L aircraft (Navy C-47As) at his disposal.

After Admiral Byrd and his team established the Little America IV base near where three previous bases had been situated, aircraft would photograph as much of Antarctica’s land surface as possible during the three-month operation. Six Martin PBM-5 Mariner flying boats were to operate from the seaplane tenders Pine Island and Currituck, photographing the east and west coasts, while the R4Ds surveyed the interior.

On November 12 Admiral Byrd stated at a press conference that Operation Highjump “was primarily a military mission to train naval personnel, test ships, planes and the new helicopters under frigid zone conditions. Develop techniques for establishing and maintaining air bases in Antarctic. A secondary objective was to increase knowledge of hydrographic, geographic, meteorological, geological and electromagnetic conditions of the area. The PBMs and R4Ds would play a major role in the objectives.” A second, unstated objective was to prove Navy capabilities to President Harry Truman, who sought reductions in America’s postwar military budget.

The Soviets eyed the Operation Highjump announcement warily. One of their naval journals stated, “U.S. measures in Antarctica testify that American military circles are seeking to subject the polar regions to their control and create military bases.”

The operation involved significant planning and equipment, from gloves, coats and provisions to tiny snow boots to protect sled dogs’ paws, and even a Christmas tree and Santa Claus suit since the ships would be at sea on December 25. Thousands of pieces of bamboo were carved and had orange flags attached to be used as route and landing zone markers.

Task Force 68 consisted of three separate naval groups, each with a specific mission. Captain George J. Dufek commanded the Eastern Group, with Pine Island carrying three PBM Mariners. The Western Group, commanded by Captain Charles A. Bond, included Currituck with the other three Mariners. Admiral Cruzen’s Central Group and the aircraft carrier Philippine Sea, with Byrd as officer in charge, filled out the task force.

The PBM flight crews were all inexperienced volunteers, having only had a month to train for the mission. One crew member characterized the flying as “no weather stations, inhuman landscape, traditional navigation aids useless, maps limited, knowing that the flying would not be safe. You were trapped in an aircraft for five hours, in zones where the weather changed minute by minute.”

Recommended for you

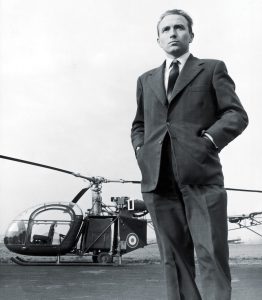

The operation also involved several Sikorsky HO3S-1 helicopters, capable of a carrying a pilot, three passengers and cargo, with a 360-mile range. The smaller Sikorsky HNS-1 accommodated a pilot and one passenger and had a range of 130 miles. One key aspect of the preparations was the construction of special platforms on the ships for the helicopters and hours upon hours spent practicing takeoffs and landings.

Flying out ahead of the icebreakers to search for clear passages through the ice, the helicopters served as the eyes of the fleet. One helicopter was allotted to each of the icebreakers and one to the carrier Philippine Sea. Besides conducting reconnaissance, each was large enough to undertake rescue operations. Two helicopters would be lost during Operation Highjump.

The Central Group was the command center for the operation. Its ships broke through the ice with the help of the Coast Guard cutter Northwind and the new Navy cutter Burton Island, which joined the operation later. Northwind was critical to the mission since the thick ice could crack open a thin-skinned ship like a can opener. Norwegian trawlers in the area reported the ice to be the heaviest in more than 40 years.

Upon reaching the Ross Ice Shelf, the Central Group ships would disgorge the small aircraft, ice vehicles, supplies, tents and sled dogs. Then the men would move inland to establish Little America IV, headquarters for Byrd and his six R4Ds.

Getting the big Douglas birds to Antarctica presented a formidable challenge as, lacking the range to fly from a land base, they had to be launched from Philippine Sea. Each was outfitted with aluminum skis attached to the landing gear struts, with the tires providing a two-inch clearance between the skis and the carrier deck. In order to get airborne, each R4D was outfitted with four JATO (jet-assisted takeoff) bottles. It was a one-way trip to Little America IV since they could not land on the carrier and would be left behind when the operation was completed. The tail, wings and midsection of each aircraft were painted with bright orange stripes for enhanced visibility in case they went down on the ice.

The Eastern, Western and Central group ships departed at different intervals and ports on both coasts. Northwind left Norfolk, Va., on December 2, headed to Antarctica via the Panama Canal. The ships stationed in the Pacific left San Diego, Calif., the same day. The Central Group and Philippine Sea did not depart Norfolk until January 2, 1947. The carrier was the last to arrive due to the construction of the base and airfield.

Grumman J2F-6 Duck amphibians with the group performed reconnaissance, supply and, if needed, rescue and medical missions. Once the expedition ships reached heavy ice, the HNS-1 helicopter was employed to fly at 600 feet and act as a scout to radio where clear openings were. Safe passage involved ships operating at low speed, wending their way through the ice.

The low temperatures made the air denser and increased the helicopters’ efficiency. Even so, 60 minutes of prep time was required to heat the fuel, oil, engine and remove any ice from the rotor blades prior to a mission. Operating from Pine Island, an HO3S-1 carrying Captain Dufek flew to Scott Island on a reconnaissance mission. During its return flight the rotor blades became so coated with ice that the helicopter crashed several feet short of the ship’s landing pad. The HO3S-1 was lost but Dufek and the pilot were saved before freezing to death in the frigid water.

The first Central Group ships arrived at the Ross Ice Shelf on January 17. The next two days were spent searching for a site for Little America IV. Then the tractors, jeeps, M29 Weasels, bulldozers and other snow-track vehicles were unloaded. The base comprised large tents, weather equipment, Quonset huts, three packed-snow runways and one short runway made of steel matting. Lieutenant Jim Cornish had the honor of flying the first helicopter in and out of Little America IV. By the time Operation Highjump was completed on March 1, a dozen helo flights had been made to the base.

On January 22, Philippine Sea lost an HO3S-1 helicopter when it was caught in strong winds on takeoff and crashed into the sea. The pilot was rescued but the accident was indicative of the hard lessons learned by pilots and crew in the early days of helicopters.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

The carrier was within 600 miles of Little America IV on January 29, close enough for the six R4Ds to prepare for takeoff. The flight deck was only 300 feet long, but with the JATO assist the first aircraft, with Byrd aboard, was airborne in 100 feet. A second aircraft took off and both made it to Little America IV safely. As the weather closed in the next day, the remaining four R4Ds followed and reached the base with only an hour to spare before conditions deteriorated. Upon landing it was judged advisable to remove the aircraft tires and only employ the skis.

During Highjump the six R4Ds completed 28 photographic flights and captured more than 21,000 images. The helicopters and PBMs also flew photo missions along the coasts. At the completion of the operation, more than 70,000 photos had been taken and over 1.5 million square miles of territory had been surveyed. “Our hope is that now we have the entire material to make a detailed map of all of Antarctica,” said Byrd.

Flying in subzero conditions meant that the oil in each aircraft had to be heated, special fuel was used and the engines were warmed up for a long time prior to takeoff. Ensuring that all the ice was removed from the propellers, wings and tail surfaces was also critical.

Besides photo equipment, each aircraft carried various instruments to search for mineral deposits and other geological features. On one of Byrd’s flights magnetic instrument pods detected a massive coal deposit. When a lake was discovered in a large ice-free patch of land, a PBM landed to scoop up water samples.

The experiences of the PBM-5 Mariner George 1 were indicative of the difficulties airmen faced during Operation Highjump. The aircraft’s launch had been delayed for days by fog, snow squalls and heavy seas. Finally, on December 26, the weather cleared and allowed for aerial mapping of the east coast. George 1 was lowered over the side of Pine Island and almost immediately one of the launch boats crashed into a wing and damaged a pontoon. The Mariner had to be lifted back onto the ship for repairs.

When the weather cleared again on December 29, George 1 was once more lowered over the side and took off with a crew of nine, including Pine Island’s skipper Captain Henry H. Caldwell, who was along as an observer. The other two Mariners were launched shortly afterward. Each PBM carried survival equipment consisting of 100 days’ worth of rations, skis, sleds, medicine, warm clothes and sleeping bags.

After they had been flying for three hours, the weather took a turn for the worse. George 1 climbed to 1,000 feet to get above the snow and ice. Instead it became involved in what is known as an “ice blink,” with streams of snow reflecting the sunshine and making it difficult to see—similar to the reflections experienced while driving a car at night through a snowstorm.

Unable to see the ground, pilot Ralph LeBlanc struck an object and tried to pull up, but the fuel tank ripped open and the aircraft crashed in a fireball. Two crewmen were killed instantly when they were thrown through the propeller blades.

For 13 days weather conditions prevented any attempt to search for the downed PBM. Finally a search plane spotted burned wreckage and men on the ground. Their signal, painted on the wrecked Mariner’s wing, indicated that three of the crewmen were dead. Since it was impossible to land in the area, messages were dropped directing the survivors to make their way to the open water about 10 miles to the north. An aircraft marked the route with orange flags and then proceeded to parachute drop food, medicine and other supplies.

The men successfully made the trek—a feat in itself—and were brought back to Pine Island by the rescue aircraft. George 1’s radioman Wendell Henderson, flight engineer Frederick Williams and navigator Maxwell Lopez had been killed. Pilot LeBlanc would lose both of his badly burned and frozen legs.

In another dramatic incident, during a four-plane flight to map as far as the South Pole an R4D carrying Admiral Byrd almost met a similar fate. After dropping a United Nations flag over the South Pole, Byrd’s crew continued their photo mission. Suddenly one of the engines seized and they began to lose altitude. Facing the prospect of an emergency landing and difficult rescue, Byrd ordered any item that was not bolted down thrown out of the aircraft, save for the photographic material. The R4D slowly began to gain altitude and in the tradition of the tough Douglas aircraft arrived back at Little America IV and made a safe landing.

As winter approached the weather deteriorated—only five days were favorable for flying in February. Soon the process began to shut down the operation and leave before the full force of winter set in.

The R4Ds’ fuel, oil and other fluids were drained. Tail sections were dismantled and stored in the hope that a future expedition could reassemble the transports and use them again. Sadly, this was not to be. By 1958 the ice shelf on which Little America IV was sited had broken away and drifted into open water. The six aircraft disappeared.

Among other losses, a PBM had been blown overboard off Currituck in a massive ocean storm prior to reaching the objective and disappeared in the high waves. A second Mariner suffered damage to its nose.

The stars of Operation Highjump appeared to be the helicopters employed by the fleet. In his report, Northwind’s commander, Captain Charles W. Thomas, emphasized, “Helicopter best piece of equipment ever carried on ice vessels.” He further noted that “In a well organized ice convoy, the commander needs to know what his ships will encounter within the next day….Hence helicopter reconnaissance within a radius of twenty five miles was essential….Battering a track through 650 miles of ice in eighteen days would not have been possible without helicopter reconnaissance. Had the Task Group penetrated the pack without ‘eyes’ it would have arrived too late in the season to establish a base; then conduct an aerophotographic exploration of a hidden continent. In other words, the Central Group would have been obliged to turn about and get out of the pack before being able to erect Little America No. 4.”

Operation Highjump was chronicled in a film shot by military photographers and narrated by Hollywood actors Robert Taylor, Robert Montgomery and Van Heflin, all of whom had served in the Navy during WWII. Released in movie theaters as The Secret Land, it won the 1948 Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.

Other operations would follow, including the U.S. Navy’s Operation Windmill in 1947-48, and eventually treaties were signed by all involved nations to ensure that Antarctica remained a nonmilitary zone.

Jim Trautman is the author of Pan American Clippers: The Golden Age of Flying Boats and is currently working on a book about airship history, due next year from Firefly Books. Additional reading: Report of Operation Highjump: U.S. Navy Antarctic Development Program 1947, produced by the U.S. Navy; and Operation Highjump: Diary of a Young Sailor, by Richard J. Miller.

This feature originally appeared in the September 2021 issue of Aviation History. Don’t miss an issue, subscribe!