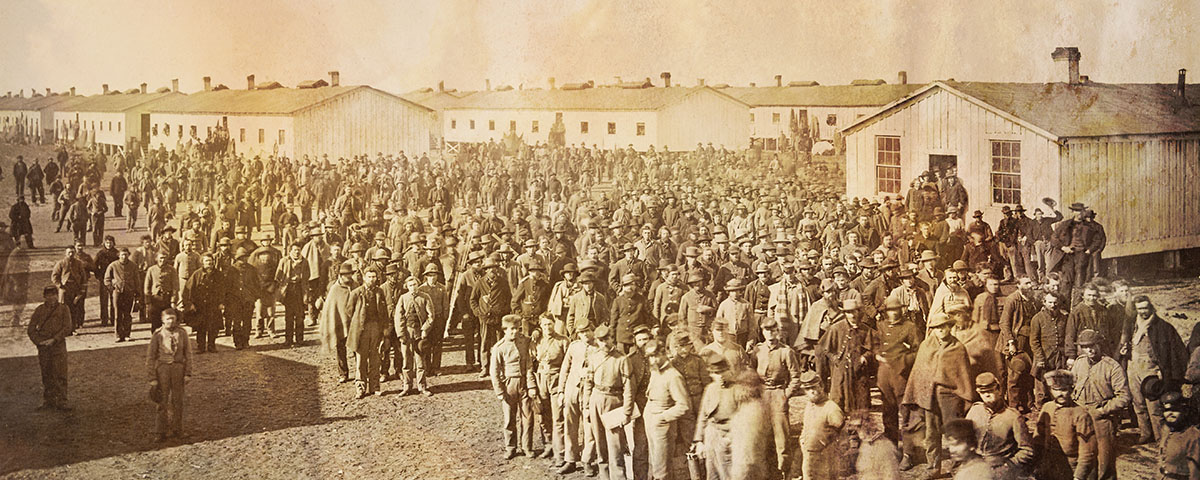

During the Civil War, more Confederate soldiers died at Chicago’s Camp Douglas than on any battlefield.

IT WAS FEBRUARY 1862, AND ON THE OUTSKIRTS OF CHICAGO, A SMALL CROWD GATHERED and watched anxiously as several thousand Confederate prisoners of war climbed out of a long string of boxcars. Under the guard of Union soldiers, augmented by local police officers and volunteer constables, the captives—“traitors,” the Chicago Tribune branded them—marched some 400 yards to the gates of Camp Douglas, a Union army camp that had been hastily repurposed as a military prison to accommodate them.

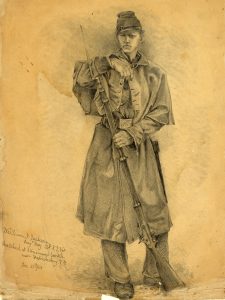

The arrival of the Confederate POWs, who vastly outnumbered their guards, had been a source of worry for some in Chicago who feared that the camp couldn’t contain them. What if they broke free and attacked? But once Chicagoans got a look at the defeated soldiers, the fears surely dissipated. The prisoners, who had no winter coats or blankets, had endured several days of travel on unheated boats up the Mississippi River to Cairo, Illinois, and then more exposure to frigid temperatures during the 300-mile train trip to Chicago.

“A more motley looking crowd was never seen in Chicago,” Mary A. Livermore, a Union army nurse, would recall years later. “They were mostly un-uniformed, and shivering with cold, wrapped in tattered bed quilts, pieces of old carpets, hearth rugs, horse blankets, ragged shawls—anything that would serve to keep out the cold and hide their tatterdemalion condition.”

Another onlooker observed that the prisoners’ toes stuck out of their worn-out boots as they trudged through the snow. They were weak from diarrhea and bronchitis, and many of the bedraggled captives’ faces showed evidence of measles and mumps.

But somehow the Confederate POWs struggled on, just a few more yards, until they were inside the walls of Camp Douglas. Within a week more than 200 of them were in the hospital, with several hundred more being treated outside. Before long even more of their comrades would join them. For many, the camp would be their final destination.

ANDERSONVILLE, THE CONFEDERATE PRISON CAMP IN GEORGIA WHERE NEARLY 13,000 UNION soldiers died from disease, malnutrition, and brutal mistreatment in 1864 and 1865, became forever infamous after its commandant, Henry Wirz, was tried and executed as a war criminal after the war. The Union’s most notorious POW camp, though largely forgotten today, was on Chicago’s South Side, just four miles from the city’s downtown. Camp Douglas, which from February 1862 until July 1865 housed some 30,000 Confederate prisoners (as many as 12,082 of them at a time), was one of the longest operating prison camps during the war. No one knows exactly how many prisoners died at Camp Douglas, but Union records indicate that at least 4,000 Confederates perished there, mostly from smallpox, dysentery, and other diseases, and some estimates put the number as high as 6,000.

Southerners came to revile Camp Douglas. But in the tragic scheme of things, the camp wasn’t so much an aberration as an example of the deprivations many prisoners of war endured in a conflict that no one expected to last as long as it did, in an era before the rules of how combatants should treat prisoners were clearly established. (The Civil War, in fact, would cause such rules to be written.)

“Neither side was prepared to handle POWs and neither figured out how to successfully remedy the situation once it presented itself,” Jennifer Caci and Joanne M. Cline wrote in an article on prisoner of war camps published in 2009 in the U.S. Army Medical Department Journal. “Repeating the same mistakes as others, from the atrocious depravities to establishing inadequate facilities, Americans had failed miserably at their first test as guardians of POWs.”

Why did so many die at Camp Douglas? Part of the problem was the unfortunate choice of location: a parcel of land only a few hundred yards from Lake Michigan, built on sand over a clay base that made it a quagmire during even a moderate rainfall. It was bitterly cold and windy during the winter.

The site, made up of two tracts bordering the fairgrounds used for the U.S. Agricultural Society Exhibition in 1859, was selected in 1861 by Judge Allen C. Fuller, who would soon become Illinois’s Adjutant General. Originally, the camp was envisioned as a reception center for Union recruits, and during the war some 40,000 Union soldiers were processed there. In that sense the location was a logical one. It was conveniently close to the Illinois Central Railroad, which built a station nearby and provided a way to transport troops to Cairo, the port from which Brigadier General Ulysses S. Grant staged his attacks on the Confederacy.

In early 1862 Camp Douglas’s mission abruptly shifted after Grant’s forces captured an entire Confederate army at Fort Donelson in Tennessee. The battle was one of the Union’s first major victories, but it also created a major problem: what to do with the thousands of Confederate soldiers who had been captured. Grant gave Major General Henry W. Halleck, who commanded the Department of Missouri, the job of finding a solution. “It is a much less job to take them than to keep them,” Grant said. And then, predicting that the prisoners “will prove an elephant,” Grant put them on a flotilla of rickety transport steamers with two days of rations and sent them up the Mississippi River to Cairo, Illinois, where they would be Halleck’s problem.

Halleck quickly searched for a prison site that fit certain basic criteria. It had to be far enough away from the battle lines that the Confederates wouldn’t attempt to raid it and free the prisoners. It also had to be close to a city with railroad connections, so that large numbers of captives could be efficiently transported there.

Camp Douglas met those criteria, even though its flimsy barracks and crude sewers weren’t designed to handle large numbers of occupants for extended periods. Who, after all, could have contemplated that the war would last as long as it did or that so many men would be captured and held?

NOT EVERYONE THOUGHT THAT WAREHOUSING CONFEDERATE POWs AT CAMP DOUGLAS was a good idea. “This is decidedly the joke of the season,” the Chicago Tribune sneered, when it broke the news of the prisoners’ impending arrival in mid-February. “The idea of keeping five thousand prisoners in a camp, where the strongest guard couldn’t keep in a drunken corporal, is rich. The whole population would have to mount guard and Chicago would find itself in possession of an elephant of the largest description. If authorities will give Chicago permission to hang the whole batch as soon as they arrive, let them come.”

Chicago mayor Julian Sidney Rumsey agreed. He saw thousands of Confederate prisoners as a menace that the camp’s small permanent garrison—just 469 men and 40 officers—wouldn’t be able to contain. He warned Halleck that “our best citizens are in great alarm for fear that the prisoners will break through and burn the city.” But when Halleck said that the Union didn’t have any more troops to spare as prison guards, Rumsey temporarily assigned Chicago police officers and volunteer constables to help keep watch over the enemy.

The fears of insurrection or escape turned out to be unwarranted, as most of the Confederate POWs who arrived at Camp Douglas were in too wretched a condition to resist. In time, the prisoners at the camp became a local attraction. Curious locals gathered at a hotel across the street with an observation tower that charged five cents for a peek into the camp.

Meanwhile, the thousands of prisoners streaming into Camp Douglas by the trainload adjusted to life inside a makeshift prison that was surrounded by a 12-foot-high stockade fence, with guard stations every 50 feet. Inside, it was lighted by large arc lamps. Ten feet inside the fence was a smaller wooden barrier that marked the “dead line.” Prisoners would be shot if they crossed it. Inside, prisoners lived in long, narrow wood barracks, each with a kitchen at the back that also functioned as a mess hall. At first there were two infirmaries, one for Union soldiers and the other for Confederates; a third was later added to isolate smallpox patients.

ASIDE FROM BEING TOO SMALL FOR THE NUMBER OF MEN CONFINED THERE, Camp Douglas had one particularly glaring—and fatal—flaw. When it was built in 1861, the state government had not approved funding for a sewer. As the camp filled up with prisoners, its soggy, crowded environment became a breeding ground for disease. “The lack of a sewer and proper sanitation accounted for a tremendous amount of sickness and death,” Joseph L. Eisendrath Jr. concluded in an article published in 1960 in the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society.

By June 1862 the prison population at Camp Douglas had swelled to 8,900 men, more than it had been designed to house, and the barracks had taken on a dilapidated look. Many of the inmates were sick, and 500 already had died.

A June letter from Dr. Brock McVicker, a surgeon who served as the camp’s chief medical officer, to Colonel Joseph H. Tucker, the camp’s commander, described the dire health hazard. “The surface of the ground is becoming saturated with the filth and slop from the privies, kitchens, and quarters, and must produce serious results as soon as the hot weather sets in,” McVicker warned.

When Henry W. Bellows, the president of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, a civilian watchdog organization, visited Camp Douglas that month, he similarly noted “standing water, unpoliced grounds, of foul sinks, of unventilated and crowded barracks, of general disorder, or soil reeking miasmatic accretions, of rotten bones and emptying of camp kettles.” The camp was in such bad shape, he warned, that “absolute abandonment of the spot seems the only judicious course.”

Unfortunately, that didn’t happen, and when Colonel William Hoffman, the Union army’s commissary general for prisoners (and a paroled POW himself), sought funds to improve the drainage, Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs refused the request. The prisoners, as Meigs saw it, should be made to defray the cost of their confinement to the extent possible—and thus conserve funds for the government’s chief goal of defeating the Confederacy. The 10,000 prisoners at Camp Douglas, he decided, could provide the manpower needed to keep the place clean.

It wasn’t until October 1863, with Meigs’s reluctant accession, that the much-needed sewers finally were built. (The sewers were wood-lined troughs that ran along two sides of the camp and emptied into Lake Michigan.) By then many more prisoners had died.

Bad sanitation wasn’t the only problem at Camp Douglas. The camp had 12 changes in command from 1862 to 1865, and the frequent turnover made planning and continuity impossible. Worse yet, guards were frequently selected from the new Union army recruits being mustered in at another section of the camp, and they weren’t given any training on how to handle prisoners. Eventually, in December 1863, the Union switched to relying on officers and men in the Invalid Corps (renamed the Veteran Reserve Corps in 1864), who were better prepared for the responsibility. But while the prisoners regarded many of the guards as competent and compassionate, there were also brutal ones who got away with abusing prisoners, often supported by officers who turned their backs on the wrongdoing.

In their book American Prisons: Their Past, Present, and Future, David Musick and Kristine Gunsaulus-Musick describe some of the cruelties to which Confederate prisoners were subjected. Guards sometimes forced them to pull down their pants and sit in the snow or on frozen ground for hours at a time. Others were stretched over a barrel and whipped with a belt buckle or forced to ride “the mule,” a 15-foot-high structure with a sharp saddle, with buckets of sand tied to their ankles—a punishment that left some unable to walk for hours. Solitary confinement in an underground dungeon and captivity in a small room jammed with other captives were other harsh punishments.

And while Confederate prisoners weren’t starved as their Union counterparts were at Andersonville, the diet was decidedly substandard. Each prisoner got an eight-ounce serving of beef on weekdays and a five-ounce serving of bacon on Sundays. The menu also included bread and a thin soup made from water drained from the beef or bacon with some beans or a potato mixed in. (Prisoners whose families sent them money could buy extra food from the camp’s commissaries). In June 1864, in retaliation for the mistreatment of Union prisoners by the Confederacy, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton reduced rations for prisoners even further and refused to allow vegetables to be sold to prisoners. A year earlier, Stanton had vetoed the replacement of burned barracks at Camp Douglas, saying that he was “not disposed at this time, in view of the treatment our prisoners of war are receiving at the hands of the enemy, to erect fine establishments for their prisoners in our hands.”

WHEN THE CIVIL WAR ENDED IN 1865, THE SURVIVING PRISONERS AT CAMP DOUGLAS were given new clothes and a one-way train ticket out of Chicago. But thousands of their comrades, most of them victims of disease or pneumonia, would never return home. Some of the dead prisoners were buried in the two small cemeteries on the grounds of Camp Douglas, but most were buried in Chicago’s old City Cemetery along the shores of Lake Michigan, in what is now Lincoln Park. After the Civil War the federal government was forced to find a permanent burial ground for the Confederate prisoners, and the remains of approximately 4,200 of them were reinterred in a mass grave at Oak Woods Cemetery, in Chicago’s Woodlawn neighborhood, between 1865 and 1867. (A 30-foot granite monument was installed in the cemetery in 1895 to mark the spot.) More Confederate soldiers are buried in Chicago than anywhere else north of the Mason-Dixon Line.

In December 1865, Camp Douglas itself was torn down. Eventually the camp’s old parade ground was converted into fields where returning Union veterans played a new sport, baseball, which they had learned during their wartime service. Memories of Camp Douglas gradually faded, a part of local history that few Chicagoans cared to remember. In 2014 a historical marker was erected on the site, and today an effort is underway to have Camp Douglas added to the National Register of Historic Places.

That’s only fitting, for the prison camp that was Chicago’s biggest connection to the Civil War still serves as a reminder of the terrible conditions endured by combatants who were unlucky enough to be captured. MHQ

David L. Keller is the founder of the Camp Douglas Restoration Foundation and the author of The Story of Camp Douglas: Chicago’s Forgotten Civil War Prison (History Press, 2015).

[hr]

This article appears in the Winter 2019 issue (Vol. 31, No. 2) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: The North’s Last POW Camp