For more than 50 years the town of Nicodemus, Kansas, beat the odds and its harsh surroundings to provide opportunity for former slaves and their descendants

By the late 1870s, the black population of the South was dismayed. The Civil War and the formal abolition of slavery with passage of the 13th Amendment in 1865 had not brought the equality or improved living conditions for which they had long hoped. Certainly, their freedom under the law was immensely significant yet blacks remained oppressed and impoverished. Land was available for lease or purchase, but at inflated prices, and the withdrawal of Union forces left blacks unprotected from Southerners who had violently opposed emancipation. Furthermore, as most former slaves possessed few skills other than farming, the sharecropping system that arose virtually re-enslaved them as tenant farmers.

After the dozen years of Reconstruction (1865–77), a means of escaping economic bondage presented itself to Southern blacks. The new opportunity came in the form of a budding all-black community in the Midwest, where they would be able to own land under the Homestead Act of 1862, prosper and put their past behind them. The promised land was in Kansas, the prewar free state, vital link in the Underground Railroad and adopted home of abolitionist John Brown. More important to would-be settlers, it was readily accessible by train and boat via the Missouri and Mississippi rivers. The utopian townsite was the brainchild of an unlikely duo.

In 1877, white land speculator W.R. Hill traveled to black churches in the backwoods of Kentucky to speak of a haven in Kansas for black families. Hill told of a sparsely settled territory with abundant wild game, wild horses that could be tamed and, of course, the opportunity to own land through the homesteading process. Adding credibility to the endeavor was Hill’s partner, black Tennessean homesteader W.H. Smith, who would become president of the Nicodemus Town Co. Among the other founders was Nashvillian Benjamin “Pap” Singleton, the colony’s most active promoter. While the colony was ostensibly named for the biblical figure Nicodemus—a Pharisee who sought out Jesus and later provided the embalming fluids for his burial—it is probable the name also commemorated an eponymous black folk legend who came to America as a slave and later purchased his freedom.

Posted in 1877, the earliest promotional handbill portrayed the nascent colony as a place for blacks to establish a community of self-government complete with its own militia to keep the peace. Nicodemus, it proclaimed, would be “The Largest Colored Colony in America.”

Another recruitment poster extended a further enticement:

All Colored People

that want to

go to Kansas,

On September 5, 1877,

Can do so for $5.00

The $5 covered transportation, while $1 bought one membership in the colony. On arrival, one could purchase a Nicodemus Town Co. membership certificate and a lot within Hill’s 160-acre townsite for an additional $5 or arrange to settle on homestead land for a nominal fee. For many black Southerners, the offer was too good to refuse.

The first wave of settlers to reach Nicodemus, on Sept. 17, 1877, totaled 350 men, women and children from the vicinity of Lexington, Ky. Disappointment lay in store. First, the transportation for which they’d paid had not delivered as expected. A train had dropped the settlers at the closest rail stop, Ellis, 35 miles south of the townsite, leaving them to walk and drive their livestock to Nicodemus.

“Instead of jubilation, many blacks were immediately disillusioned, and rightfully so,” says Angela Bates, founder and past president of the Nicodemus Historical Society and a descendant of those original settlers. “The contrast of the parched Kansas plain was stark compared to the green hills and rich farmland of the South. There was nothing there, just a barren, stark landscape. You could see 10 miles in any direction.”

“When we got in sight of Nicodemus,” recalled follow-on settler Willina Hickman in the spring of 1878, “the men shouted, ‘There is Nicodemus!’ Being very sick, I hailed this news with gladness. I looked with all the eyes I had. I said, ‘Where is Nicodemus? I don’t see it.’ My husband pointed out various smokes coming out of the ground and said, ‘That is Nicodemus.’ The families lived in dugouts… The scenery was not at all inviting, and I began to cry.”

Several dozen would-be pioneers returned to dim prospects in the green hills of Kentucky rather than live in such sod-roofed dugouts, constructed either by digging straight down into the bare earth or by hollowing out bluffs along the Solomon River. “Living as prairie dogs,” recalled one early settler. Many more toughed it out, despite lacking appropriate tools, clothing, food, seed and money. Some survived by selling buffalo bones found on the prairie to the fertilizer industry for $6 a ton, while others worked for the railroad in Ellis. Still others managed only with the assistance of empathetic Osages, who provided food, firewood and staples.

Bates’ maternal and paternal grandparents were among those who remained, and her family has since maintained a presence in Nicodemus. At least 65 of her family members are buried in the town cemetery, and she moved back in 1989 to organize the historical society.

In the spring of 1878, Nicodemus welcomed another 150 settlers, part of an 1878–79 mass exodus of Southern blacks. Referred to as “Exodusters,” most settled in Missouri, Illinois and Kansas. In 1870 the black population in Kansas stood at around 16,000. By 1880 it exceeded 43,000.

Despite the challenging living conditions, Willina and husband the Rev. Daniel Hickman remained, soon organizing the Mount Olive Baptist Church. Another early settler, Zachary Fletcher, became the first entrepreneur in Nicodemus, establishing a general store in 1877 and, later, the St. Francis Hotel and a livery stable. He was the town’s first postmaster, while wife Jenny served as its first postmistress and schoolteacher.

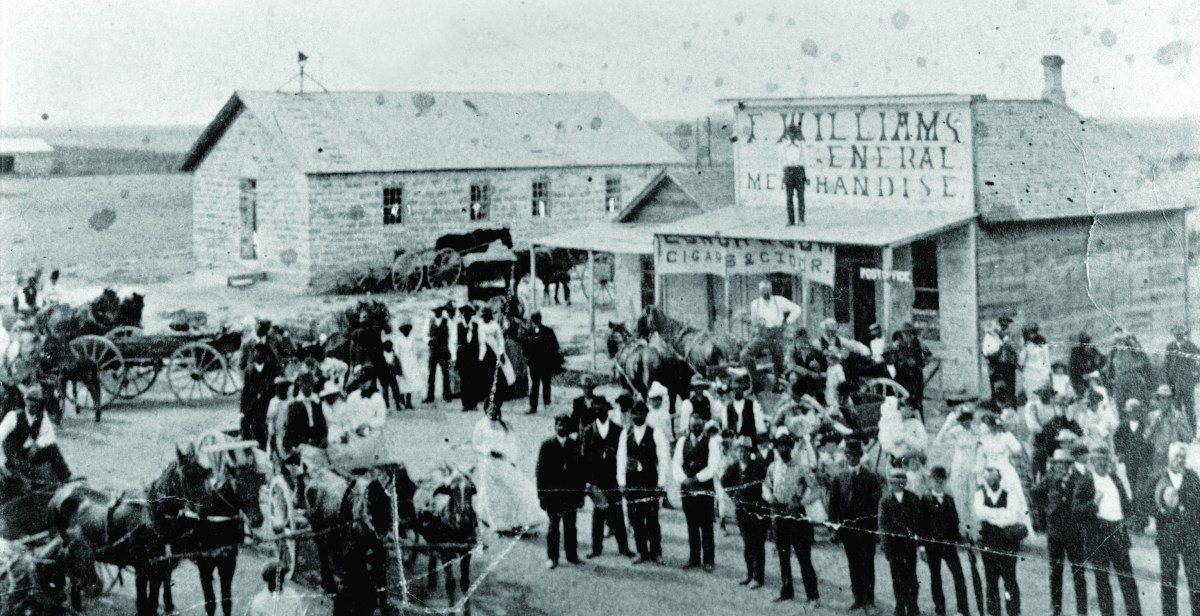

By 1880 Nicodemus had grown into a proper town, with a bank, two hotels, three churches, a drug store and three general stores ringed by a dozen square miles of cultivated land. Within a few years, residents had their choice of two newspapers, the Western Cyclone or the Nicodemus Enterprise. At the time published statistics for Nicodemus Township listed 275 black citizens, 83 whites, 31 horses, and 10 mules. The average homestead had 12 acres in cultivation. Livestock numbered 43 head of cattle and 75 hogs, while crops included 997 acres of corn, 98 acres of millet, 50 acres of sorghum and 50 acres of rice corn.

Townspeople were justly proud of the settlement they had built quite literally from the ground up. In 1887, hoping to ensure Nicodemus’ continued growth and economic viability, voters had approved the issuance of $16,000 in bonds to lure the Missouri Pacific Railroad to town. A Missouri Pacific representative had asked the township to pay for a section of line through Nicodemus, a standard arrangement between railroad companies and frontier towns.

The Cyclone was ecstatic. Boom! Boom!! Boom!!! Boom!!!! Boom!!!!! read its headline that March 24. “Last Tuesday was a day long to be remembered in Nicodemus,” the editorial read, “for that day the people decided by an overwhelming majority that we would be a crossroads post office no longer, but that ere another year should pass, that we should develop into a town…. The boom is on. Not a mere blow, but a boom that will roll on indefinitely.” In anticipation of the coming railroad line and depot, land sales boomed and many new businesses opened in Nicodemus.

Despite the bond issue and subsequent arrival of Missouri Pacific surveyors, however, the railroad hedged its bets and ultimately withdrew its offer to extend a line to Nicodemus. Meanwhile, the Union Pacific Railroad laid down tracks 4 miles to the southwest through a construction camp that soon took root as the town of Bogue. Almost immediately, most of Nicodemus’ merchants moved their operations trackside, some taking their buildings with them.

While the loss of the railroad was a difficult blow for residents to absorb, Nicodemus soldiered on as a viable community until 1929 when the Great Depression brought economic hardship. As prices for crops plummeted, people fled town in droves.

Further devastation followed when the Dust Bowl struck the region in the mid-to-late 1930s. Overplowing of the virgin topsoil had eliminated the native prairie grasses that kept the earth moist and anchored down. Amid a recurring drought, strong prevailing winds churned up the resulting dust in huge clouds known as “black blizzards” or “black rollers.”

Centered on the panhandles of Texas and Oklahoma and adjacent sections of New Mexico, Colorado and Kansas, the Dust Bowl forced tens of thousands of poverty-stricken families, including those hanging on in Nicodemus, to abandon their farms, as they were unable to grow crops and pay bills. By 1935 the town that had held so much promise had shrunk to a population of just 76 clinging to a church, a community hall and a single store.

By 1950 Nicodemus had dwindled to just 16 residents. The post office closed in 1953, the lone school in 1960. In the intervening decades, most of the homestead land has been sold, and there is scant evidence this was the location freed blacks settled in 1877 with the idea of attaining true freedom and self-government. Still, of the more than half dozen black settlements that sprang up in Kansas after Reconstruction, Nicodemus is the only one to survive, with a present-day population hovering around 20.

The townsite was designated a national historic landmark in 1976. Twenty years later, on Nov. 12, 1996, Congress designated Nicodemus a national historic site. With help from the National Park Service, Bates and other community members have committed to the preservation of Nicodemus’ historic structures and interpretation of its history. Some 5,000 annual visitors tour the townsite, about an hour’s drive northwest of Hays. Descendants of the original settlers are often on hand at the visitor center to answer questions.

“Nicodemus is an iconic symbol for African Americans, in that it represents how blacks helped settle the American frontier long before most people realize,” Bates says. “Having an important role in American history, the townsite and remaining buildings symbolize the pioneering spirit of those ex-slaves who fled the war-torn South in search of ‘real’ freedom and a chance to restart their lives. It was also an important stepping-stone in African American migration farther west.”

Since 1878 Nicodemus residents have held an annual emancipation celebration known as “Homecoming.” “After more than 142 years, every summer the town is crowded with as many as 500 people who return and are very proud of their heritage,” Bates explains. Come what may, Nicodemus’ next “Homecoming” is scheduled for July 29–Aug. 1, 2021.

Nicodemus Today

The Nicodemus National Historic Site occupies a largely treeless Kansas plain. The only remaining structures at the old townsite are a scattering of homes, a BBQ café, a new Baptist sanctuary, a senior center and the following historic buildings:

• St. Francis Hotel/Switzer Residence: Dating from 1881, this modest story-and-a-half building served as a hotel, the town’s first post office, its first schoolhouse and a stagecoach station. It was also the home of Zach and Jenny Fletcher and family, listed among the earliest residents of Nicodemus in the 1880 federal census.

• Old First Baptist Church: This 1907 limestone church must have been a welcome addition for a congregation that had begun worship in a crude dugout in 1877 before “moving up” to a prairie sod church.

• African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Church: The congregation worshipped

at another site from 1878 until 1897, when it acquired the present building from the Mount Pleasant Baptist Church.

• School District No. 1: Dating from 1918, this one-room frame building (see photo above) replaced the first freestanding schoolhouse, built in 1887.

• Township Hall: Built in 1939 of locally quarried limestone, with the help of the Depression-era Works Progress Administration, the hall served as both a community center and the seat of local government. Today it houses the Nicodemus National Historic Site Visitor Center, featuring an interpretive film and local history exhibits.

—J.W.

Missouri-based freelancer Jim Winnerman is the author of more than 1,000 articles on history, art and architecture and is a frequent contributor to Wild West. For further reading he suggests Nicodemus: Post-Reconstruction Politics and Racial Justice in Western Kansas, by Charlotte Hinger; The Black Towns, by Norman I. Crockett; and “‘Pap’ Singleton, the Moses of the Colored Exodus,” by Walter L. Fleming, from the July 1901 issue of the American Journal of Sociology.

This article was published in the February 2021 issue of Wild West Magazine. To subscribe, click here.