Late on the wintry afternoon of Dec. 5, 1797, a 28-year-old Frenchman stepped from a carriage at 6 rue Chantereine in Paris. “At first sight he seemed to me to have a charming face,” noted newly acquainted French Minister of Foreign Affairs Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, “so much do the halo of victory, fine eyes, a pale and almost consumptive look become a young hero.”

The young hero was Napoléon Bonaparte. Two years earlier the French Directory—the five-member post-revolutionary committee then ruling from Paris—had given Bonaparte command of the Army of Italy, France’s primary force along the border with that country. After resolving the army’s systemic supply and discipline problems, the ambitious general led the revitalized force to victory over five Austrian armies, the army of the kingdom of Sardinia and the forces of Pope Pius VI. He also recaptured Corsica from the British, partitioned the ancient Republic of Venice and forced peace on continental Europe. By the end of the War of the First Coalition in 1797 only Britain remained at war with the French Republic.

As word spread of the hero’s return, Paris exploded in celebration, and publishers, composers and poets praised Napo-léon in print, music and verse. In his honor government officials renamed rue Chantereine (Singing Frogs) rue de la Victoire.

But on the south side of the Seine at Luxembourg Palace the five members of the Directory—Paul Barras, Jean-François Reubell, Louis-Marie de La Révellière-Lépeaux, François de Neufchâteau and Merlin de Douai—were far less enthusiastic about Bonaparte’s return to Paris. The men suspected the young general had returned to the capital specifically to overthrow the Directory and seize control of France.

Bonaparte was no fool, however. He likely understood his public support was founded not only on his victories but also on the perception he remained loyal to the republic. If he failed to sustain that illusion, his popularity would fade as quickly as it had flowered. The surest way to maintain the support of the people, he reasoned, was to personally engineer the defeat of his nation’s sole remaining foes—the hated British.

The French Directory’s plan to force Britain to its knees centered on a cross-channel invasion, and it had assembled an army and fleet for such a campaign. Bonaparte argued, however, that France must first weaken the enemy’s commerce. Toward that end he proposed to lead an army to occupy Egypt. A successful campaign, he reasoned, would shift Continental Europe’s primary trade route to India from a long sea voyage around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope to a short, French-controlled land route across Egypt to the Red Sea. The Egyptian city of Alexandria would become a trading hub, and with French naval bases at Marseille, Toulon, Malta and Corfu, the Mediterranean would become a vast French lake.

While Bonaparte’s success would undoubtedly benefit France, it would also benefit the general personally. A fruitful campaign in the exotic “land of the pharaohs” would enhance his martial reputation even as the increasingly unpopular directors squandered what remained of their authority and public support.

The directors, for their part, relished the opportunity to send the upstart young general back abroad and out of the public eye. With luck Bonaparte would be away for years. He might even die in battle or succumb to a fatal disease.

With the blessings of the directors Napoléon formed the 35,000-man Army of the Orient, using troops largely drawn from his battle-tested Army of Italy. The force comprised five infantry divisions under generals Louis Desaix, Jean-Louis-Ébénézer Reynier, Jean-Baptiste Kléber, Jacques-François Menou and Louis-André Bon and a cavalry division under Thomas-Alexandre Dumas. In mid-March 1898 the Directory established the Commission of Sciences and Arts, a 167-member institute of engineers, mathematicians, architects, artists, writers and interpreters, most of whom would join the expedition. While their presence would lend a scholarly tone to the expedition, it would also have the unintended effect of aligning Bonaparte with France’s intellectuals.

On May 19 some 300 ships carrying the troops and equipment of the Egyptian expedition set sail concurrently from Toulon, Ajaccio, Genoa, Bastia and Civitavecchia. Once at sea they assembled under the overall command of Vice Admiral François-Paul Brueys d’Aigalliers and set a course for Malta. The fleet reached the island on June 9 and in just three days seized it from its rulers, the Order of the Knights Hospitallers of Saint John of Jerusalem—a military remnant of the First Crusade. On June 19 Napoléon left 4,000 soldiers to garrison Malta, and the fleet continued east toward Alexandria.

The French got their first view of Egypt at daybreak on July 1 and were underwhelmed. “To the west I saw the coast,” wrote artist and expedition member Vivant Denon, “which stretched like a white ribbon over the bluish horizon of the sea. Not a tree, not a dwelling; it was not just nature in her saddest array, but the desolation of nature—silence and death.” That night the troops put ashore at Marabout, 8 miles west of Alexandria. The sea was rough, and 20 soldiers drowned when their small boats capsized. Everyone, including the commander in chief, slept on the beach, wet, hungry and thirsty. At 6 a.m. on July 2 Napoléon ordered his men to their feet.

Two hours later, tired and almost mad with thirst, the French reached Alexandria, and Bonaparte ordered an immediate assault. Menou stormed the outlying Triangular Fort, while Kléber and Bon attacked the city gates. Fortunately for the French, the Egyptians had neglected the city’s once-powerful defensive wall, which in places had crumbled to the ground. “As for the weapons,” noted contemporary Egyptian chronicler Abd al-Rahman al-Jabarti, “nothing remained except some broken-down cannons, which were useless.”

Alexandria surrendered after three hours of fighting. The French suffered 300 soldiers killed or wounded—the latter including both Kléber and Menou—while the defenders lost between 700 and 800 troops. The capture of Egypt’s second city burnished Bonaparte’s martial reputation and raised the morale of his hot and thirsty army. But neither the general nor his men realized they had yet to confront Egypt’s rulers and principal defenders—the Mamluks.

Unlike the local conscripts comprising the majority of Alexandria’s defenders, the Mamluks were members of a highly trained, highly motivated male military caste. The Egyptian Mamluk ruling class had traditionally boosted its troop strength by procuring child slaves from peasant families in southern Russia and the Balkans, converting them to Islam and training them as warriors. By the late 18th century the Mamluks numbered from 8,000 to 10,000, a fraction of Egypt’s population of some 4 million people, the majority of whom were fellaheen, or peasants. A third group, the Bedouin, roamed Egypt’s vast desert tracts in the tens of thousands.

Despite their minority status, the Mamluks had ruled Egypt for 500 years. Though they were ostensibly subservient to the Ottoman sultan, two Mamluk beys (chieftains), Ibrahim and Murad, exercised the real power. After Alexandria fell, Murad met in Cairo with Ibrahim and the other Mamluk leaders, who resolved to seek help from Ottoman Sultan Selim III. In the meantime, Murad lead an Egyptian army against the French. “What do we have to fear from the French?” he reportedly scoffed. “If they land 100,000, it will suffice to meet them with untrained young Mamluks, who will cut off their heads with one slice of their scimitars.”

When word of the gathering enemy force reached Napoléon in Alexandria, some 130 miles northwest of Cairo, he immediately ordered the bulk of his Army of the Orient to march on the capital. One column under General Charles Dugua (replacing the wounded Kléber, whom Napoléon had assigned to garrison Alexandria) would march east along the Mediterranean coast to Rosetta, at the mouth of the Nile. There Dugua’s troops would rendezvous with a flotilla of riverboats under naval Captain Jean-Baptiste Perrée. Shadowed by the flotilla, the infantrymen would march upriver (south) to link up with the second French column at el Rahmaniya. The latter column comprised the bulk of the French army—some 25,000 men—and included the divisions of Desaix, Reynier, Bon and Honoré Vial (replacing the wounded Menou, who garrisoned Rosetta). To reach el Rahmaniya on schedule, Napoléon ordered his divisions on a 60-mile march due east across the merciless desert.

The column set out on July 7. By the end of the first day men suffering from blistered feet, sore eyes and exhaustion lagged behind the column. To straggle was to die, for Bedouin marauders harassed the march, robbing and killing all who couldn’t keep up. The French cavalry was unable to protect the column, for the number of riders was relatively small, and their horses were weak from the voyage. Parched soldiers soon exhausted the column’s water supply. When one division paused en route at a well, desperate soldiers trampled 30 of their fellows to death in the rush for water, while others, finding the well dry, killed themselves.

When the French finally reached el Rahmaniya, Captain Jacques Miot recalled, “The whole army, as if by one impulse, rushed by thousands into the Nile. It was not enough to drink of its water. They did not stop to take off their clothes, but ran in as fast as they arrived, that every limb might partake of the refreshment, and that they might drink at every pore. No sound of drums, no command of their officers could restrain them.”

Mamluk riders appeared even as the French joyously refreshed themselves in the Nile. Murad had marched north from Cairo along the river, shadowed by a flotilla of armed feluccas (lateen-rigged sailboats). With 800 cavalrymen he trotted forward along the riverbank and watched as French officers frantically herded their soldiers back into the ranks. Bonaparte formed squares six men deep, the first rank kneeling with bayonets pointing outward as the others prepared to fire over their heads. The French cavalry and transport sheltered in the center, and sweating artillerymen dragged their cannons to the corners of the squares.

Unfamiliar with the European square formation and the dangers it presented, Murad ordered a probing charge. His horsemen rode into a withering hail of cannon and musket fire. Those few Mamluk riders who managed to make it to the edge of the squares fell to the bayonets of the French infantry. Survivors wheeled into the desert, leaving behind some 40 dead and wounded. Murad wisely ordered a general withdrawal. The next day Dugua’s southbound column arrived in el Rahmaniya, followed by Perrée’s flotilla. The Army of the Orient was reunited, and Bonaparte had gained a week on Murad at the cost of only a few hundred French lives—most to the desert and scavenging Bedouin.

At dawn on July 13 Bonaparte learned Murad was deploying his newly reinforced army a few miles upriver around the village of Shubra Khit. The Egyptian commander had assembled some 4,000 Mamluk cavalry supported by 10,000 fellaheen infantry, while on the Nile nine or 10 feluccas stood ready to attack the French flotilla.

Napoléon marched upriver to meet Murad. To protect his left flank from the Egyptian gunboats, the French commander ordered Perrée upriver with his flotilla. Unfortunately, a strong tailwind propelled the French gunboats into contact with the enemy well ahead of the infantry. The Egyptians opened up on Perrée’s flotilla with land-based artillery, then followed up with a naval assault, soon claiming three of the French vessels. To relieve the embattled flotilla, Bonaparte hurried his soldiers forward and formed them into squares. Ignoring the lessons from el Rahmaniya, the Mamluk horsemen again charged directly into the French guns, most toppling from their horses, dead or wounded, before they could strike a blow. Even as Murad’s riders faltered, French naval gunners scored a lucky hit on the magazine of the Mamluk flagship, blowing it from the water. Murad again ordered a retreat.

Keeping the Egyptian army on its heels, Bonaparte ordered his exhausted men to march on Cairo, some 80 miles to the south. “Our sufferings,” Miot recalled, “now greatly increased. All the villages were deserted, and the soldiers had not bread to eat, though we actually lay upon heaps of corn. We were totally without animal food, though there were fruits in abundance. The Arabs, always hanging on our flanks, cut off all stragglers.”

As the march dragged on, one irate grenadier reportedly hollered out to Bonaparte, “Are you taking us to India?”

“Not with such soldiers,” the indefatigable general shot back for all to hear.

Resignations poured in from the French officers. Bonaparte disregarded them. “The officers complained more loudly than the soldiers,” he later reflected, “because the comparison was proportionately more disadvantageous to them. In Egypt they found neither the quarters, the good table nor the luxuries of Italy.”

But while the soldiers might complain, and the officers give notice, all knew only one course remained open to them—to follow Napoléon.

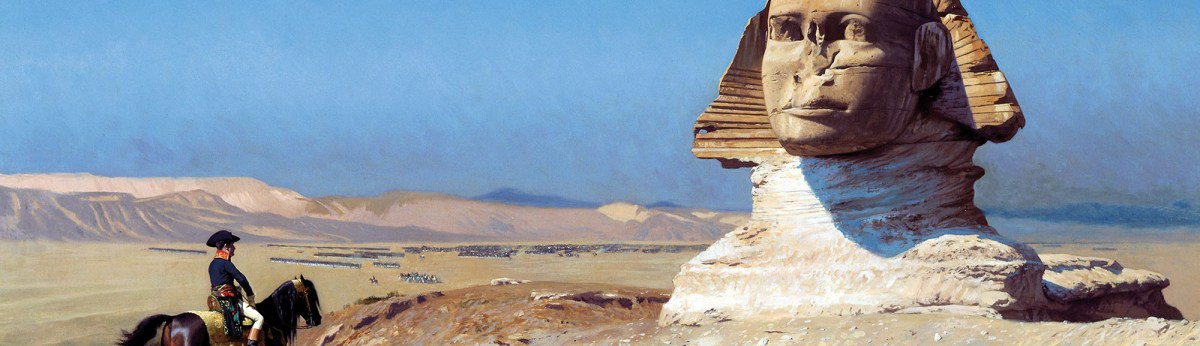

On July 21 the French army finally neared Cairo. Bonaparte had some 22,000 infantrymen, a few thousand cavalrymen and 40-odd cannons. “The Mamluks were extended before us in a long and splendid line,” Miot recalled. “The novelty and splendor of their appearance, their glittering colors and standards, excited a general admiration among us. Never was displayed a more impressive scene. On the left was the Nile, and Cairo beyond it, with all its hundred minarets and domes; on the right were the Pyramids, the highest, the oldest, the most durable of the works of men. Bonaparte pointed to them when he gave the word and exclaimed, ‘Remember that from the summit of yonder monuments 40 ages are beholding us!’”

Murad anchored the right of his line on the Nile at the village of Embabeh, where he stationed 40 guns and 15,000 infantrymen. On his left he positioned his 6,000 Mamluks. For reasons that remain unclear, his fellow commander, Ibrahim, had massed his 18,000 infantrymen and all his artillery across the river, where they would have little effect on the battle.

Despite their weak positions—and poor recent performance—the Mamluks were supremely confident. “[The Mamluks were] contemptuous of their enemy, unbalanced in their reasoning and judgment,” conceded Egyptian chronicler al-Jabarti. “[They] saw themselves as fighters in a holy war. They never considered the number of their enemy too high, nor did they care who among them was killed.”

About 2 p.m. Bonaparte ordered Desaix and Reynier to take up position on the French right and prepare to seal off the enemy’s only viable route of retreat. Noting the movement, Murad sent an elite Mamluk cavalry corps in a sweeping charge against the flanking enemy divisions.

Captain Jean-Baptiste Vertray was in Reynier’s division. “[We] had the honor of being the first attacked,” he recalled. “General Reynier gave the command, ‘To your ranks!’ and in the twinkling of an eye we were formed in square six men deep, ready to sustain the shock.…Scarcely had the order to commence firing been given, when a cloud of cavalry surrounded us.”

Screaming “Allah! Allah!” Mamluk riders swarmed around the French squares, firing pistols, hurling lances and slashing with razor-sharp scimitars. In reply Napoléon’s disciplined riflemen drove thousands of well-aimed musket balls into the careening horsemen. “The rifles of the French were like a boiling pot on a fierce fire,” al-Jabarti wrote.

The Mamluk torrent swept around the unbreakable French squares of first Reynier’s division and then Desaix’s until finally ebbing to the south, leaving behind hundreds of dead and wounded. “I seized that moment,” Bonaparte recalled, “and ordered General Bon’s division, which was on the Nile, to go in to attack the fortifications [at Embabeh], and General Vial…to move between the force which had just charged and the emplacements.”

Vial’s and Bon’s soldiers poured over the entrenchments into the village. “Here, the Mamluks had 30 or 40 pieces of cannon,” Miot recalled, “which they knew so little how to use that they had not time to load them for a second discharge. They were routed at the point of the bayonet; some of them had their clothes set on fire by our muskets and were in this dreadful manner burnt as they lay mortally wounded.” Scores of panicked Egyptian soldiers drowned attempting to swim the Nile as Murad and other survivors fled south. Witnessing the slaughter from across the river, Ibrahim’s men also ran for their lives.

“When the people saw that Ibrahim Bey and his followers had fled,” al-Jabarti recalled, “they took to their heels and ran like the waves of the sea in such a way that the cleverest among them became he who ran faster than his neighbor.”

The Battle of the Pyramids, as the fight became known, cost Murad perhaps as many as 3,000 Mamluk horsemen and untold infantrymen. Bonaparte, by contrast, lost just 40 killed and 260 wounded. The next day the French occupied Cairo and its citadel.

Once the euphoria of victory faded, however, the morale of Bonaparte’s soldiers again plummeted. “All goes very ill,” cavalry commander Dumas wrote to Kléber from Cairo six days after the battle. “The troops are neither paid nor fed, and you may easily guess what murmurs this occasions…loudest perhaps among the officers.”

Moreover, the Egyptian people viewed the French as heretics, not liberators. “They have intercourse with any woman who pleases them and vice versa,” al-Jabarti wrote. “They do not shave their heads nor their pubic hair. They mix their foods. Some might even put together in one dish coffee, sugar, arak [distilled spirits], raw eggs, limes and so on.”

The French mutually detested the Egyptians. “Once you enter Cairo, what do you find?” Major Jean-François Detroye reflected rhetorically. “Blind men, half-blind men, bearded men, people dressed in rags, pressed together in the streets or squatting, smoking their pipes, like monkeys at the entrance of their cave; a few women of the people, hideous, disgusting, hiding their fleshless faces under stinking rags and displaying their pendulous breasts through their torn gowns; yellow, skinny children covered with suppuration, devoured by flies.”

Morale within the Army of the Orient plunged even lower in early August when news arrived that a British fleet under Rear Adm. Sir Horatio Nelson had destroyed the French expeditionary fleet at anchor in Aboukir Bay near Alexandria. Bonaparte’s men were stranded. A month later Ottoman Turkey declared war on France, and Sultan Selim III amassed large armies to drive the French from Egypt. Coming months witnessed Bonaparte’s invasion of Syria, his repulse at Acre and his temporary reprieve with a 1799 victory ashore at Aboukir.

For the French the expedition to Egypt was a futile misadventure, its only lasting achievement an exhaustive tome on the region published by the Commission of Arts and Sciences. But the cost paid for the 23-volume Description de l’Égypte was dear: Of the 35,000 soldiers sent to Egypt, nearly 9,000 perished.

Despite his failure, however, Bonaparte experienced a decidedly different outcome. On Aug. 23, 1799, he abandoned his army, transferred command to Kléber and stole away to France, again receiving a hero’s welcome. A month after his return he overthrew the Directory in a bloodless coup and wrested control of the French government as first consul. As he had foreseen, the expedition to Egypt laid the foundation for the next step in his career.

Through his remaining days Bonaparte expressed fond memories of his time in Egypt. “I found myself freed from the obstacles of an irksome civilization,” he told one contemporary. “I was full of dreams.…I saw myself founding a religion, marching into Asia, riding an elephant, a turban on my head and in my hand a new Quran that I would have composed to suit my needs. In my undertakings I would have combined the experience of the two worlds, exploiting for my own profit the theater of all history, attacking the power of England in India.…The time I spent in Egypt was the most beautiful of my life because it was the most ideal.”

The long-suffering soldiers he had abandoned in Egypt held quite a different view, one expressed in the words of a song written by Antoine-Charles-Louis de Lasalle, who joined the expedition as a major and later became a celebrated general in his own right:

The water of the Nile is not champagne

Why make war where there are no cabarets?

James W. Shosenberg writes from Oshawa, Canada. For further reading he recommends Bonaparte in Egypt, by J. Christopher Herold; Napoléon’s Egypt, by Juan Cole; and Memoirs of the French Expedition to Egypt and Syria, by M. Jacques Miot.

First published in Military History Magazine’s May 2017 issue.