Hard-working immigrant mama built a business empire buying and selling stolen goods

Fredericka Mandelbaum came to America in 1850 with little more than the clothes she was wearing. She moved into a Manhattan slum, worked hard, invested shrewdly, and, earning the nickname “Mother,” built a million-dollar business. Mother Mandelbaum’s rags-to-riches story would be truly inspirational except for the fact that she made her millions buying and selling stolen goods.

Mother Mandelbaum was, in underworld parlance, a fence—“the smartest fence in America,” according to the Brooklyn Eagle. The New York Times went further, in 1884 labeling Mandelbaum “the nucleus and center of the whole organization of crime in New York.”

Mandelbaum was big, standing nearly six feet and weighing well over 250 pounds. She dressed conservatively, in dark clothing of the finest silk or wool, black hair pulled into a bun and topped with her trademark hat—a black bonnet festooned with feathers. Mother wanted to look like a lady because, as she frequently said, “it takes brains to be a real lady.”

Born in Hanover, Germany, in 1827, Fredericka Wiesener married peddler Wolf Mandelbaum in 1848. In 1850 Wolf and then Fredericka emigrated to New York City, settling on the Lower East Side in a dingy one-room apartment in Klein Deutschland—”Little Germany.” They raised four children while peddling rags and used clothing in the street.

A shrewd businesswoman, Fredericka quickly realized that she could acquire better goods at lower prices if she bought from thieves. Soon, she was enlisting neighborhood urchins to do the thieving, and setting up an informal academy on Grand Street that taught pocket-picking, burglary, and safecracking.

She exhibited maternal concern for young female crooks, especially Sophie Lyons, a neighborhood teenager whose parents had been sent to prison. Mandelbaum took the girl in and trained her in the criminal arts. Lyons matured into a world-famous con artist before going straight. Decades later, she remembered Mother in a memoir. “I was very happy because I was petted and rewarded,” Lyons wrote in Why Crime Does Not Pay. “My wretched stepmother patted my curly head, gave me a bag of candy and said I was a good girl.”

Business boomed. In 1866, Fredericka and the bedridden Wolf rented a three-story building at the corner of Rivington and Clinton streets. The Mandelbaums, who eventually bought the property, lived upstairs and ran a semi-legitimate street-level dry goods emporium while out back Fredericka went about her felonious fencing trade.

Wolf Mandelbaum died in 1875. His widow thrived. She developed a stable of skilled thieves who agreed to sell their loot exclusively to her. In return, she suggested targets for burglaries, bailed out busted second-story artists, and paid notorious shyster lawyer William Howe a $5,000 annual retainer to defend her operatives in court. Mother’s inventory of hot goods grew so fast that she was driven to buy warehouses. Her preferred commodities were diamonds, gold, silk, and fancy sterling silverware. She sold the gems and gold to jewelers, the silk to dressmakers and shopkeepers, and the silverware to hoteliers and restaurateurs as far away as Cincinnati.

Mother shared the wealth, donating to cops and pols, asking only to be left alone, unburdened by intrusive government oversight—like the enforcement of statutes against selling stolen property. Palms sufficiently greased, the authorities cooperated, and everybody was happy, except the people whose stuff got swiped.

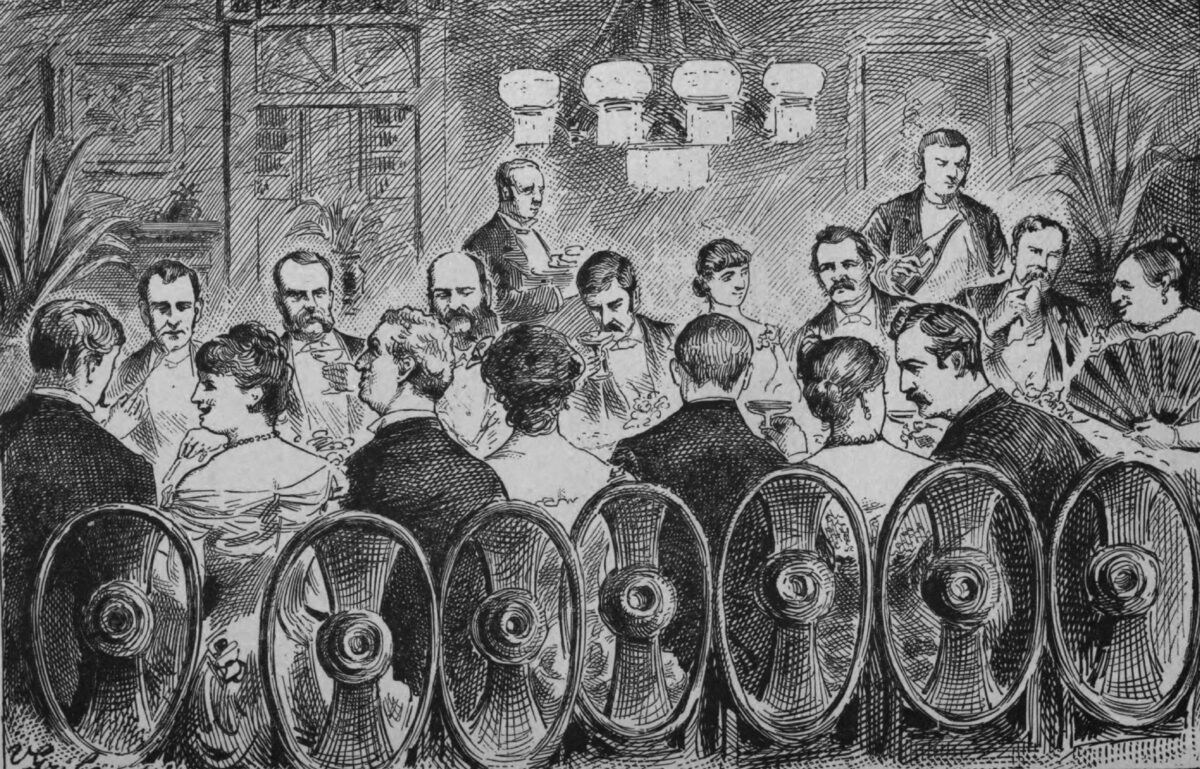

Mandelbaum threw elaborate dinners in her pad, decorated with elegant chandeliers and furniture, mostly stolen. At her parties, thieves and grifters mingled with bent cops and pols like Tammany Hall sachem William M. “Boss” Tweed. Guests washed down lamb and steaks with fine wines and listened as expert safecracker “Piano Charlie” Bullard played Beethoven sonatas. Mandelbaum was so fond of Bullard’s playing that when police in Yonkers arrested him for robbery in 1869, she hired a gang of thieves to bust him out of jail.

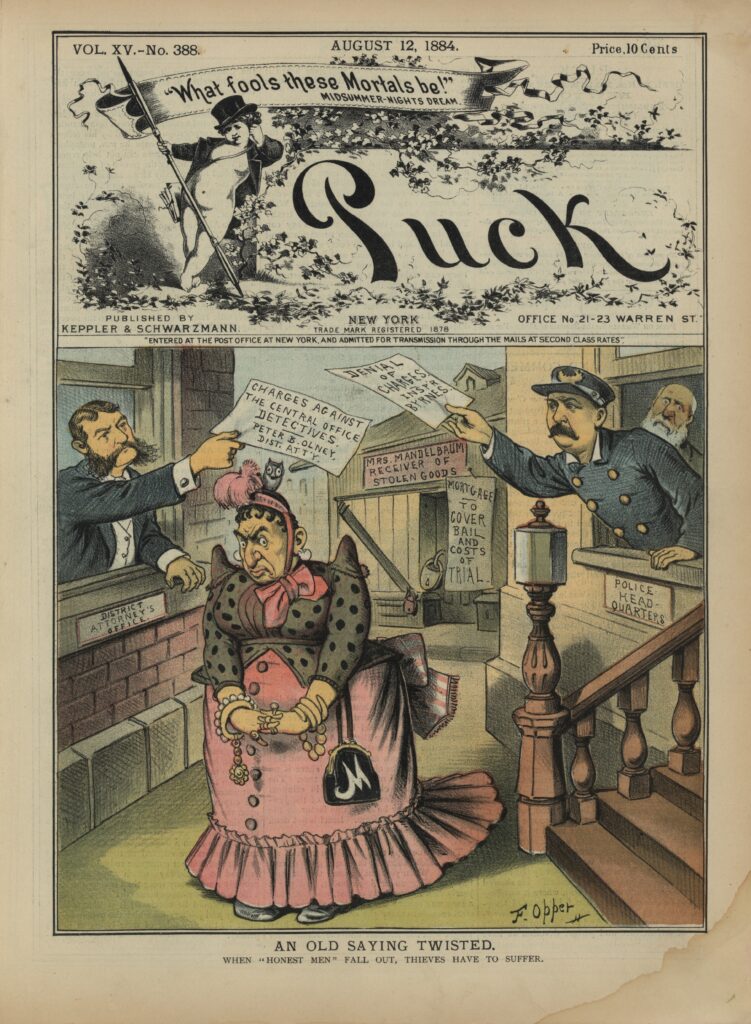

For 20 years, Mother’s dinners dazzled guests—until 1884, when she found herself targeted by a rarity in Gilded Age Manhattan: a straight-arrow lawman. Appointed district attorney the year before and wanting to prove he was honest, Peter Olney decided arresting the notorious Mother Mandelbaum would seal his reputation. Knowing she had the police force in her pocket, he kept his project secret. To infiltrate Mother’s fencing operation, Olney hired Gustave Frank, a Pinkerton detective. Posing as Stein, a crooked silk dealer, Frank gained Mother’s trust. During a five-month period, she sold the impostor 12,000 yards of stolen fabric. On July 22, 1884, “Stein” served Mandelbaum a warrant in her carriage outside her store.

“You wretch, you!” Mother said. And she punched him in the face.

His nose bleeding, Frank arrested Mandelbaum, along with son Julius, 24. Suspicious of judges in lower Manhattan, Olney arranged to book the pair in Harlem, charging them with grand larceny and receiving stolen property.

Papers headlined the busts—“THE QUEEN OF FENCES HELD FOR TRIAL”—and Mother’s arraignment drew a packed courtroom. “My name is Fredericka Mandelbaum and I am 52 years old. I am a widow,” she said in a statement read by her lawyer. “I keep a dry goods store and have done so for 20 years. I have never knowingly bought stolen goods…”

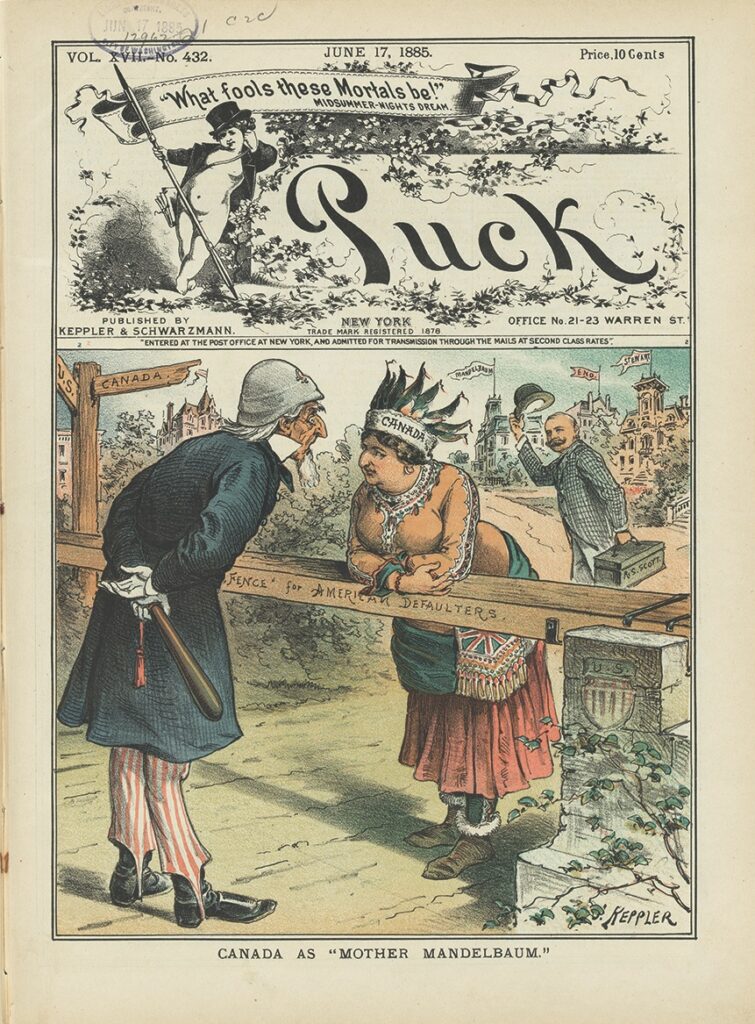

Released on $10,000 bail, Mother realized she and Julius couldn’t beat the rap. They gave their Pinkerton shadows the slip and skedaddled to Canada, which had no extradition treaty with the United States. Explaining his clients’ abrupt emigration in court, her attorney told the judge: “I believe Mrs. Mandelbaum acted upon Mark Twain’s theory that absence of body is often better than presence of mind.”

Mother went into exile rich. In Hamilton, Ontario, she bought a two-story house, joined Anshe Sholem Hebrew Congregation, and opened a dry goods store—“in every respect the equal of my late New York establishment,” she declared.

When daughter Annie, 18, died in 1885, Mandelbaum sneaked into the funeral. The police ignored her. Reporters asked how she liked Canada. “I’m tired of it,” Mother said before fleeing back north. “I’m sorry I ever left New York.” She was 66 when she died in 1894 in Hamilton, Ontario—where, the paper Hamilton Spectator wrote, residents regarded her as “a woman of kindly disposition, broad sympathies, and large intelligence.”

The clan laid its materfamilias to rest in the family plot at Union Fields Cemetery in Queens, attended by friends, neighbors, cops, pols, and many aging felons. Afterward, several mourners told police that their pockets had been picked at Mother’s grave.

This story appeared in April 2020 issue of American History.