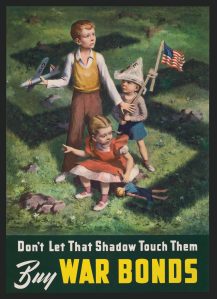

In answer to the Dec. 7, 1941, Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, the Doolittle Raid sought to bolster the morale of stunned Americans and warn the Japanese their country was now the target of a determined foe. Sixteen Army Air Forces’ B-25Bs launched from the carrier Hornet on April 18, 1942, to bomb the Japanese Home Islands. While relatively small in scale, the raid had lingering repercussions. Eight of the 80 crewmen were captured and tortured. Three were executed for “war crimes.” Last Mission to Tokyo: The Extraordinary Story of the Doolittle Raiders and Their Final Fight for Justice is equal parts courtroom drama, survival story and history lesson. Author and Defense Department attorney Michel Paradis has led cases at Guantanamo Bay and in war-torn regions. He is a lecturer at Columbia Law School and a frequent contributor to NPR, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal and other media.

Why did you write this book?

One of the things that made the story fascinating is that it’s a true-life legal thriller based on one of the most famous missions of World War II. It highlights the stakes like other war crimes cases couldn’t. I’ve been involved in a fair number of war crimes cases, on all sides and in different places, including Guantanamo and Central America. Anyone who has done these cases understands they are not normal. There is a political context that sometimes overwhelms the law. When I stumbled upon this case and saw that it involved the Doolittle Raid, it made it so much more true to life.

Much of Last Mission to Tokyo revolves around the postwar trial. Why?

Much of Last Mission to Tokyo revolves around the postwar trial. Why?

The book starts with the execution of three of the Doolittle Raiders—William Farrow, Dean Hallmark and Harold Spatz—then jumps a few months back in time to cover the actual mission. But the story is really about the trial and seeking justice. This is the first time this story has been told. It was highly publicized back then, but faded from memory.

What happened to the raiders?

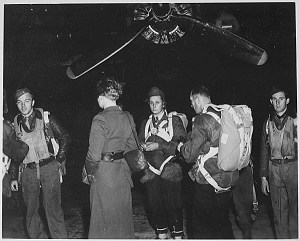

The miraculous thing is they not only succeeded in attacking Japan, but 69 of them, including James Doolittle, escaped capture and returned home as heroes. Eleven were not so lucky. Three died in the effort. Eight others were captured by the Japanese in China. They were taken into custody by the secret police, subjected to brutal torture and taken to secret prisons. Tojo, the prime minister, asked lawyers in the war ministry if there was a lawful way to condemn the Doolittle Raiders. They came up with a plan to try them under international law as war criminals before a military commission and execute them.

The eight Americans went before a show trial. The Japanese needed evidence to show they committed atrocities, so the military presented signed confessions. They were all sentenced to death, but only three were executed. The emperor commuted the sentence of five to life in solitary confinement. One died in captivity but the other four were rescued in August 1945 by members of the OSS who weren’t even looking for the Doolittle Raiders.

‘The eight Americans went before a show trial. The Japanese needed evidence to show they committed atrocities, so the military presented signed confessions. They were all sentenced to death, but only three were executed’

Tell us about the trial.

After the war the Army’s judge advocate—a colonel by the name of Edward “Ham” Young—implemented war trials in the Pacific. He was a real lawyer’s lawyer and one of the founders of modern military law. Young wanted justice for the raiders. He interviewed the survivors, who told this harrowing story, and handed it to Robert Dwyer to build a case. When the murders of the raiders were publicly announced in 1943, President Franklin Roosevelt promised those responsible would be held personally accountable.

Dwyer put the judge, prosecutor, general in charge and prison warden on trial. These were the people who perverted justice by doing the paperwork for murder. It was a radical innovation in the law and not certain to succeed. Dwyer was a bulldog of a prosecutor and was relentless in putting the case together.

On the other side was Edmund Bodine, a combat pilot who had been awarded the Silver Star. He became the defense lawyer for the Japanese, despite the fact he was not actually a lawyer. He understood he was there to look good failing. His involvement meant the Japanese got a fairer trial than they gave the raiders, but no one thought anything but the gallows awaited the four Japanese officers.

Bodine committed to the case in surprising ways. He got to know the defendants and understand them as human beings. By the time the trial started in 1946, Bodine was committed to ensuring they’d get a fair trial.

Why did the Allies want to hold war crimes trials?

Roosevelt insisted we have proper trials to demonstrate justice. He got a lot of resistance to that. Joseph Stalin came around—he loved a good show trial—but Winston Churchill remained opposed. He was totally consistent with history. The idea that you would lay waste to your defeated enemies was a given. It’s a credit to Roosevelt and then Harry Truman for insisting the Allies temper revenge with justice. This idea we were going to impose peace through fairness is important. As a historian of warfare, I see that moment as one of the great leaps forward in humanity. And it worked! Germany and Japan became some of our most reliable allies for the next 75 years.

Who are the book’s heroes?

Bodine and Dwyer are heroic figures, even though they are antagonistic. Young is an unsung historic figure.

Doolittle is an incredibly heroic figure. You can’t overestimate the significance of the Doolittle Raid in terms of both galvanizing American morale and causing the Japanese to make tactical and strategic decisions that turned out to be catastrophic.

‘Rather than sending the four men to the gallows, a military commission convicted them of some charges, acquitted them of others and gave them all sentences of five years, except for one, a lawyer. He received a nine-year sentence, because he should have known better’

Why is this trial so important?

What transpired is an inspiring debate between Dwyer and Bodine, two imperfect men of genuine good faith fighting for what is right. And the outcome shocked everybody. Rather than sending the four men to the gallows, a military commission convicted them of some charges, acquitted them of others and gave them all sentences of five years, except for one, a lawyer. He received a nine-year sentence, because he should have known better.

The outcome stunned the United States. It was such a politically controversial decision that Congress promised an investigation. There were letters to the president and Gen. Dwight Eisenhower demanding the trial be redone so “proper” sentences—of death—could be imposed.

Young, the judge advocate, wrote a 60-page report, ultimately concluding that justice was done. This is what makes American justice special. It established a precedent that became international law. The values of fair trials and equal justice became part of the Geneva Convention of 1949.

True justice is not the outcome-oriented response the Japanese pursued against the raiders. It is understanding the accused individual. You are holding people accountable for crimes while getting to know the person behind the act and then deciding what is just. That’s what justice is.

What’s your takeaway from this project?

The idea that humanity can get better. It takes standing up for what is right when it is not politically expedient or socially acceptable. If you follow your conscience, humanity can get better—but that is the only way it does.