An 84-year-old man looks back at life inside Minidoka War Relocation Center.

I used to have a recurring nightmare until I was about 11 or 12 years old. The dream was so vivid that I often woke up covered with sweat. Images included a dark but featureless street, the haunting hum of war machinery, and a woman whom I took to be my mother. An underlying feeling of fear dominated. The dream was real and frightening.

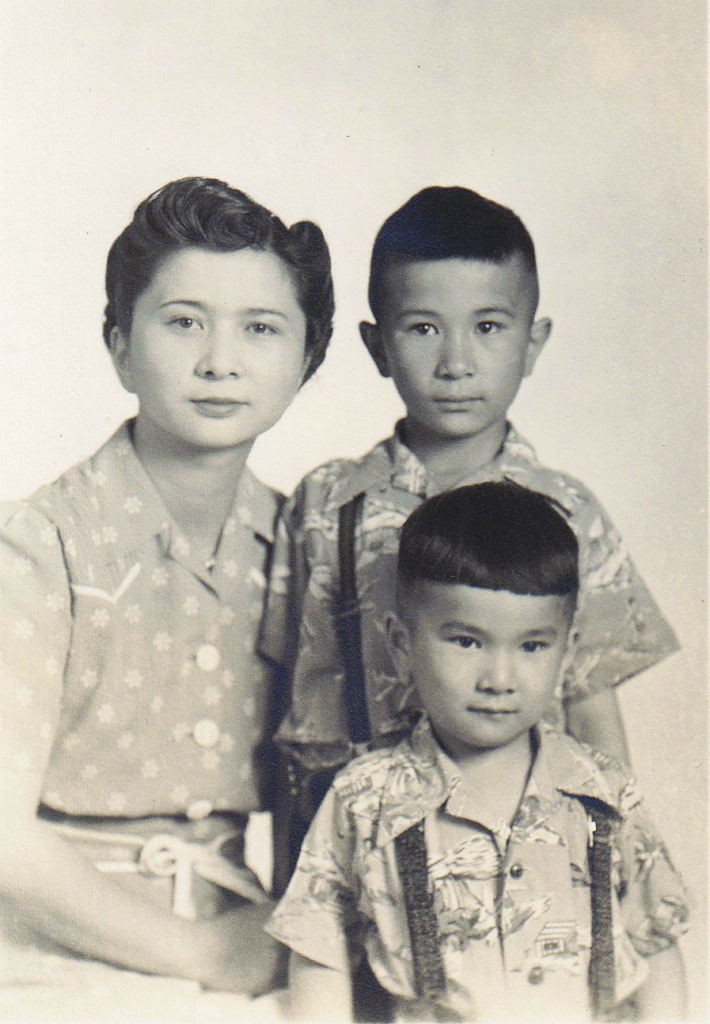

I am 82 years old today. In March 1942, I was four when my family boarded a bus at the beginning of our journey from Seattle, Washington, to Minidoka War Relocation Center, a fenced-in, 600-building compound in southern Idaho that would become our new home for the next three years.

I felt my mother’s anxiety on that bus, facing an uncertain future without clear answers to her questions: Where will we ultimately be sent? Japan? Will we still be Americans? Will we be harmed? Can we ever return home? Looking back, I feel a strong connection between my nightmare and my mother’s anxiety on that bus.

And what do I remember about camp? How much of it is colored by my later experiences, maturation, and my adult understanding of the fundamental violations of our civil rights? I search my memory for experiences of Minidoka as a kid aged four to seven, trying not to impose my adult perspective, keeping in mind that I’m seeing these events through my reconstructed childhood eyes.

I have only a few memories from before the war, such as enjoying a fried egg sandwich in Seattle’s old Oregon Hotel, and tripping over a man’s leg in front of the court house that left me with a scar on my face—but the majority of my life at that early age is a blank.

I remember camp years better. My first memory is the departure on that Greyhound bus from Seattle. I was sitting on my mother’s lap—the mood was gloomy, enhanced by Seattle’s gray sky and a light rain. Puyallup, Washington, our first stop, was the site of a temporary camp built on the grounds of the state fair. People on the bus were talking quietly and weren’t lively or excited, as they would have been if they were going for a day out to the fairgrounds.

I must have felt my mother’s anxiety. I do not remember her talking about the war or camp with me during the trip, or even during our years there. These were matters for adults; the child’s world revolved around more immediate everyday concerns, such as finding the latrine, standing in line at mess halls, and not embarrassing our parents.

My memories of Puyallup center on two main topics: ordinary matters of getting through the day, and the war. Certain events stand out, like the companionship of many children shouting and playing, and buying popsicles at the camp fence across from a grocery store, where outsiders would stand by the fence, take orders and money, and return with the popsicles—the thrill of getting treats was palpable. The place felt exciting, with many children to play with and a freedom to wander the fairgrounds. I especially delighted in making parachutes from handkerchiefs, standing on an elevated platform, throwing them up in the air, and watching them float down. I used these memories to tell post-war friends that camp was fun, ignoring the negative consequences for adults who had lost jobs, businesses, and homes.

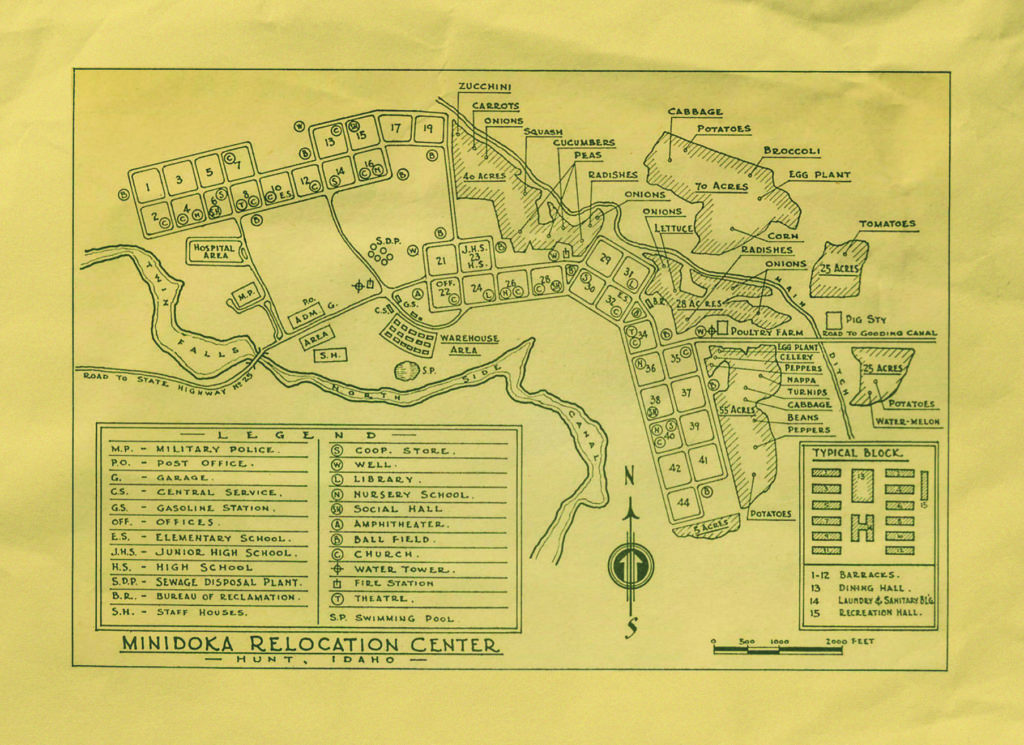

My focus on playing with other children continued on to our final destination—Minidoka, an internment camp surrounded by barbed wire and guard towers located in Hunt, Idaho, in a flat desert covered with sagebrush. (Note that while the term “internment camp” is commonly used, I and many others prefer different, more accurate terms, such as “incarceration camp.”) The soil was a fine dust that seemed to be unavoidable whether outside or indoors. About 8,000 Japanese Americans lived here, making it one of Idaho’s largest population centers. We were divided into blocks, which were organized in a military fashion with each block consisting of 12 barracks surrounding a latrine/bathhouse and a mess hall. Each barrack had 6 rooms; my family of four shared a room of approximately 15 by 20 feet.

My home was 36-6-D or block 36, barrack 6, apartment D. On cold days we heated a potbelly stove with coal. I remember distinctly sitting near the stove, melting glass marbles on the edge. Since I did not remember our life in Seattle, I had no reference to know that we were living in very spartan quarters. I accepted having to urinate into a tin can at night, since going outside to the bathhouse during wintertime was a real challenge. But, nevertheless, on cold days I delighted in jumping on thin layers of ice between chunks of frozen earth, feeling the crunch of broken ice beneath my feet. Since we were limited to bringing to camp only the things we could carry, we had very few toys and for fun we made do with whatever materials we could find, such as wood scraps from construction projects—and certainly crunching ice was fun, like popping plastic bubble wrap.

Every block became a small village, and Block 36 was like all the others. We were in constant contact with each other, whether sharing showers, eating in the mess hall, or just hanging out with friends. When we met people we didn’t know, the first question asked was often what block we lived on. When blocks competed in baseball games, we would root for our “home team.” The central focus was always the mess hall, where we had three daily meals and time to talk and gossip. Like any village, Block 36 was a community where everyone knew all the goings-on.

I don’t remember much about meals except that I especially loved sauerkraut and Vienna sausages. My mother in her later years mentioned she hated Columbia River smelt, a common food in the mess hall that I do not recall eating. The milk glasses were large, round, and thick, and the plates were heavy white commercial ware. As a small boy, it was awkward for me to use these heavy glasses and dishes. I don’t specifically recall eating with other children or my parents, but I do remember a constant cluster of people who were familiar with each other. The mess hall was also a social gathering place for special events such as Christmas, with a live Santa who gave out simple gifts. Everyone celebrated Christmas, whether your family was Christian or Buddhist. My family was Christian all the way back to my grandmother from Bainbridge Island near Seattle. Block members decorated the hall and competed with other mess halls for the best holiday decorations. I looked forward to these events because they made these days special.

As a child, I was naturally drawn to other children. There were plenty of kids to play with, and subsequently groups of children who teased each other. So it was not a paradise of constant fun and games, but instead a setting for regular interactions that resulted in normal friendships and frictions. In other words, this was like any neighborhood where playing and conflicts were everyday matters.

I recall being teased, especially by older children, probably because I appeared younger than my age. Two older girls from three barracks away bullied me, calling me “sissy” and other names. The older boys constantly made comments about me being a crybaby. In retrospect, I recognize that they were socializing me and the other younger children on the value Japanese Americans placed on being tough, putting up with troubles, and not crying or complaining, especially when others caused us harm. Adults reminded us about being honorable by emphasizing that our actions reflected on our parents, and that we should never lose face. Older youth reinforced these and other adult mores by showing us how we should behave.

I remember one embarrassing event when the older boys encouraged a boy younger than me to have a snowball fight with me. As they shouted support for the other kid, who was getting the best of me, I felt angry and put a piece of coal in a snowball and threw it at him, hitting and injuring him. I felt bad that I hurt him, and the older kids scolded me while they sought help for his wound. Afterward, the older boys talked sternly to me while I sat and remained silent. I worried that my mother would hear about this incident. She worked in the camp hospital emergency room and treated the boy, but she never said a word about it. I felt so embarrassed that I tried to forget and not mention the incident, but I could not forget it, and in retrospect it reinforced the power of older boys over me.

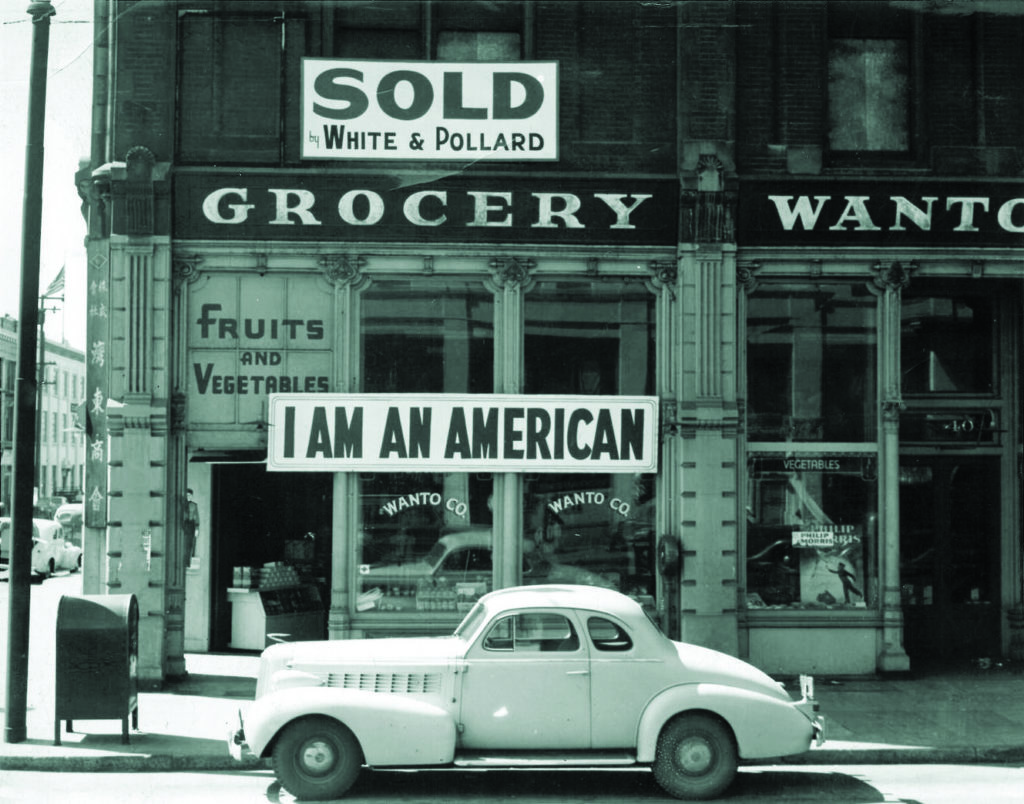

The war. I knew there was a war going on because of a parade for Ben Kuroki, a Nebraska-bred, Japanese American U.S. Army Air Forces war hero who visited camps and encouraged young men to volunteer for military service. I was stirred by the military sounds of the Boy Scout Drum and Bugle Corps preceding the car carrying Kuroki through camp. In Minidoka, there was a special pride in having sons join the U.S. Army, and talk about being American was openly heralded—but with the underlying sense that we were still Japanese.

People on Block 36 talked about the young men who went to war, most joining the 442nd Regiment, the all-Japanese American unit that went on to become the most decorated American army unit of World War II. Stories circulated of Japanese Americans fighting in Europe who showed exemplary heroism in battle, supporting the notion that we were something special—brave, tough, non-complaining, and loyal. Parents in some barracks hung flags with blue stars on their windows, signifying that their sons were in the army.

I can recall seeing pictures of the war in Life magazine and hearing older boys talk about what was happening. I distinctly remember admiring some B-17 bomber graffiti on a bathroom wall, and when I later made my own stick airplane, I drew a Japanese rising sun on the wings. I wasn’t sure it was such a good idea and didn’t show it to many of my friends. This simple toy reflected the contradiction of being caught between our two worlds—we were Americans and yet also somehow Japanese.

Older men conveyed to younger ones that Japanese were braver than others, reflecting their pride in being Japanese regardless of whether they were fighting for Japan or America. My grandmother was born in Japan, spoke little English, read Japanese papers, and worried about her family in Japan. She said little about her feelings on the war, except for playing patriotic Japanese records, which I found very moving. I can remember the lyrics and music to this day. My Japanese was a fragmented, child’s version of Japanese—kudomo nihongo—so I had few direct conversations with her except for mundane matters such as going to the bathroom. Nevertheless, she was an important link to my Japanese heritage.

My parents did not openly speak about the war, but they did worry about what would happen when we left Minidoka. The military’s policy regarding our freedom of movement evolved during our years there. At first, we faced barbed wire and guard towers but soon we saw lesser restrictions, and eventually a more relaxed policy even permitted travel outside of camp. My father was given permission to visit Chicago in 1944 to see if we should move there. I remember this distinctly because he brought back ping-pong balls. Other than this, I had no real sense of a post-camp future until the day we packed to go back to Seattle.

The change in the camp authorities’ attitudes was also evident in my own experiences exploring the fence surrounding Minidoka and the guard tower near our barrack. Toward the end of our stay, I delighted in climbing the empty guard tower, a stark contrast to the early days where I feared getting close to it. By the very end, the barbed-wire fence was simply a barrier that kids could crawl under without due alarm.

The irony of camp is that while we were Japanese and we were in the midst of a terrible war, the hakujin (white people) who worked there did not treat us offensively. I can’t ever recall being called “Jap.” My white teachers were kind and we looked forward to attending school. Outside volunteer hakujin who visited us were usually associated with Christian outreach programs—they treated us with respect and included us in Christian services. I remember Reverend Andy, a Baptist preacher, who visited frequently and made us feel a part of America.

Occasionally we were allowed a day pass to visit Twin Falls, the closest city, to go shopping, but I do not recall being mistreated there, either. My main memory of Twin Falls is stepping on worms that filled the sidewalk on rainy days, but I had no sense that I was the enemy.

My experiences in camp differed from those of my older cousins, who were angrier because they had different expectations. Fumi and Ozzie had their high school educations disrupted. Hiro believed that Japanese Americans—who were American citizens—should be protected by the Constitution. What about due process when we were incarcerated? I did not have those expectations but simply went with the flow of what I was experiencing, like playing games and just getting by with others in what was home to me.

In the spring of 1945, we left Minidoka. As the war was ending, the government made the decision to close the relocation camps, encouraging residents to move East to avoid any large concentration of Japanese Americans on the West Coast. Instead, my parents decided to return to Seattle, which they felt was their home. I was seven years old, leaving behind the only home I had ever really known. I asked my older brother, Paul, what Seattle was like. He described a place with fantastic imagery of lush green vegetation, unlike the camp’s desert of sagebrush, and wonderful tall buildings like in the movie The Wizard of Oz. In preparation for leaving, I filled my mother’s empty face-powder box with sand as a reminder of Minidoka. Unfortunately, on the train back to Seattle, my brother and I had an argument over the sand. In the process of fighting, the sand spilled out and I lost my keepsake of camp.

Arriving at the train station in Seattle, the view more than fulfilled my expectations, seeing Smith Tower, at the time the tallest building west of the Mississippi. And yes, the vegetation glowed green and Oz-like—the city’s nickname, the “Emerald City,” made perfect sense. What excitement and high expectations of my new home I had; I did not anticipate the anti-Japanese experiences that lay ahead for me.

Our new next-door neighbor, owner of the corner grocery store, had a sign in his store window: “No Japs allowed.” People referred to me as the “Jap kid.” I was beaten up by a schoolmate who called me “Jap.” Before the war, Japanese Americans did experience racism, but I did not. I was only a small child then. But I suffered these insults as a seven-year-old boy, about to turn eight. Of course these experiences redefined the meaning of camp as a traumatic event symbolizing that we were not true Americans. To this day, even though I am the third generation of my family in America, I am sometimes still seen as a “foreigner” or “stranger,” even if I’m no longer seen as a “Jap” or the enemy. No matter how benign my treatment at camp, Minidoka was a symbol of my stigma.

Ironically, Minidoka had insulated me from the racism thrown in my face after the war. The experiences of camp raised the question of my identity—Japanese or American. As a child, I did not have the means to compare myself and understand what it meant to be a “normal” citizen. Nevertheless, I experienced emotional trauma inadvertently through my mother, whose anxieties were transmitted to me by non-verbal means. The repeated nightmare was evidence of the feelings of uncertainty and fear we were all experiencing.

As I grow older, I see myself not as an outsider but as a citizen with responsibilities to stand for a more just country. I realize now that my childhood camp background is behind my desire to be a witness to stand up for modern-day “Japs”—all people who face similar prejudices as my family and I did. Ever since camp, I hear of others—Southeast Asians, Muslims, Central Americans, and others—who are still seen as strangers or as outsiders, whether they are first-generation Americans or if their families have been here for many generations.

While my childhood nightmares no longer plague me, Minidoka put a scar on my heart. I almost felt I had to apologize for having been there. But, to be a normal American, you had to not fuss about it, as that would somehow make you feel less patriotic or like a permanent second-class citizen. For the longest time, I had to apologize for my existence as an outsider. I cannot forget—and have come to realize that my experience has been repeated throughout history. The story of The Trojan Women by the Greek-era tragedian Euripides describes one such event. Watching a recent production of the play so reminded me of my past. At the end of the play, captured Trojan women and children are boarded on ships going to an unknown future. In the last scene, they are singing a mournful song lamenting their fate, their voices fading as they head farther away from home. I cried for myself—it was me on that journey. ✯

This article was published in the February 2020 issue of World War II.