IN EARLY 1944 I was 17 years old, in my senior year at Eastern District High School in Brooklyn, New York, and, after several summers spent working as a comic at Catskills resorts, knew that I wanted to go into show business. But Hitler had started a war.

One day a U.S. Army recruiting officer came around and said that if anybody in the class scored high enough on an aptitude test, they could join the Army Specialized Training Reserve Program, the ASTP Reserve. If you were accepted, you would graduate early from high school and be sent to a college paid for by the government. Then when you turned 18 and joined the army, you would be in a better position to choose your field of service. This sounded great to me. I knew I was destined to be drafted anyway. So I took the test. I think they really wanted everybody they could get. Some of the questions were not too difficult, like “2 + 2 = what?” Needless to say, I passed. I was sent to college at VMI, the Virginia Military Institute in Lexington, Virginia, for special training.

Life there was wonderful and terrible. The terrible part was getting up at 6 a.m. to shave, shower, and have breakfast. And having to make my own bed with hospital corners. The wonderful part was that the VMI cadets were so welcoming to us ASTP Reserve trainees. They never resented our sharing the school with them. VMI was not just an academic college. Founded in 1839, it was known as “the West Point of the South.” In addition to my academic studies of electrical engineering and learning all about cosines, tangents, slide rules, and such, they also trained you to be a cavalry officer. So I learned to ride a horse and wield a saber—something I had never seen any kid from Brooklyn do.

When I turned 18, I was officially in the army. They sent me to Fort Dix in New Jersey, which was an induction center. And even though I had spent a semester studying electrical engineering at VMI, the army in its great wisdom decided that I should be in the field artillery. They shipped me out to Fort Sill, Oklahoma, the Field Artillery Replacement Training Center. When reduced to its initials, it spells FARTC. (Which somehow lingered in my subconscious and later made its way into a comedy scene in my film Blazing Saddles. Waste not, want not.)

Fort Sill is in the southwest corner of Oklahoma. It’s cold, it’s flat, and it’s windy. If you ever have a chance, don’t go there.

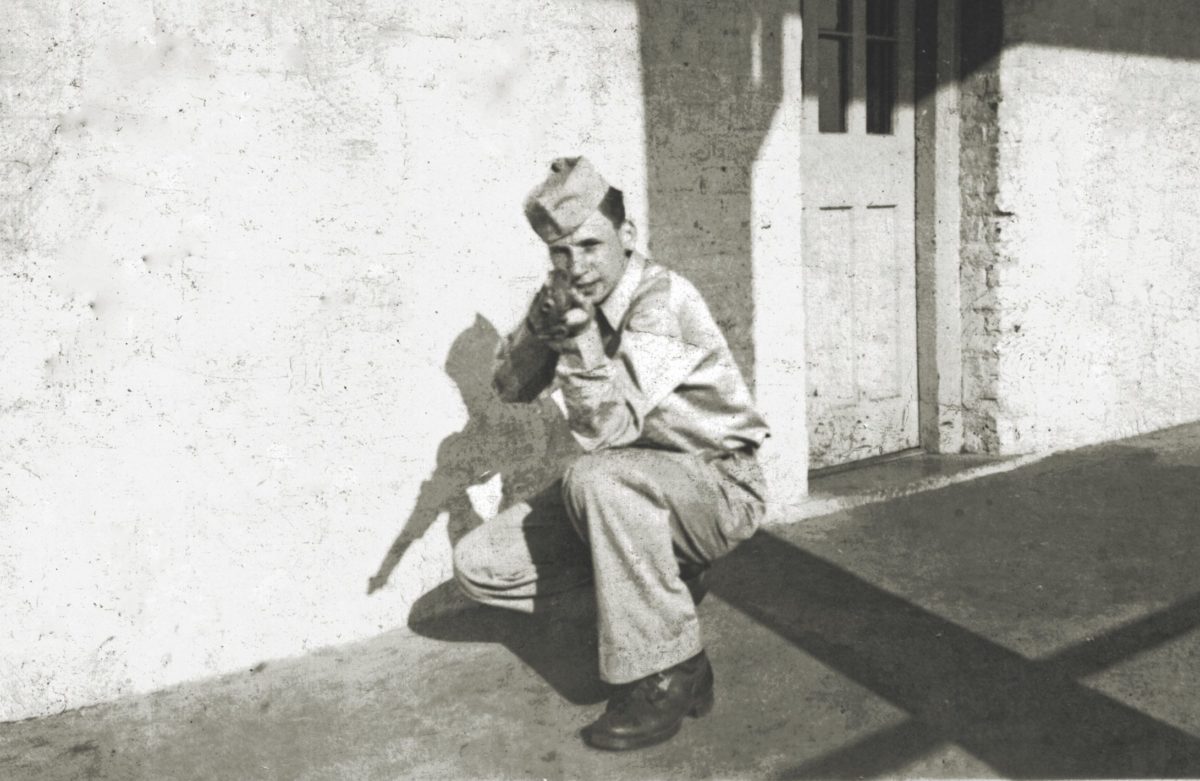

Having gone to VMI, basic training at Fort Sill wasn’t that difficult. You learn how to carry a rifle, how to drill with a rifle, and how to shoot a rifle. And we’d go on long marches—5, 10, occasionally 20 miles—with only 10-minute breaks. That was tough. Then there’d be the infiltration course, where they tested your skills and used live ammunition while you kept your head down and crawled on your elbows and your knees. That was scary.

The more reassuring part was that I was trained to be a radio operator. That was going to be my job when I went overseas with a field artillery unit.

No ‘Shortcutting’ the jam

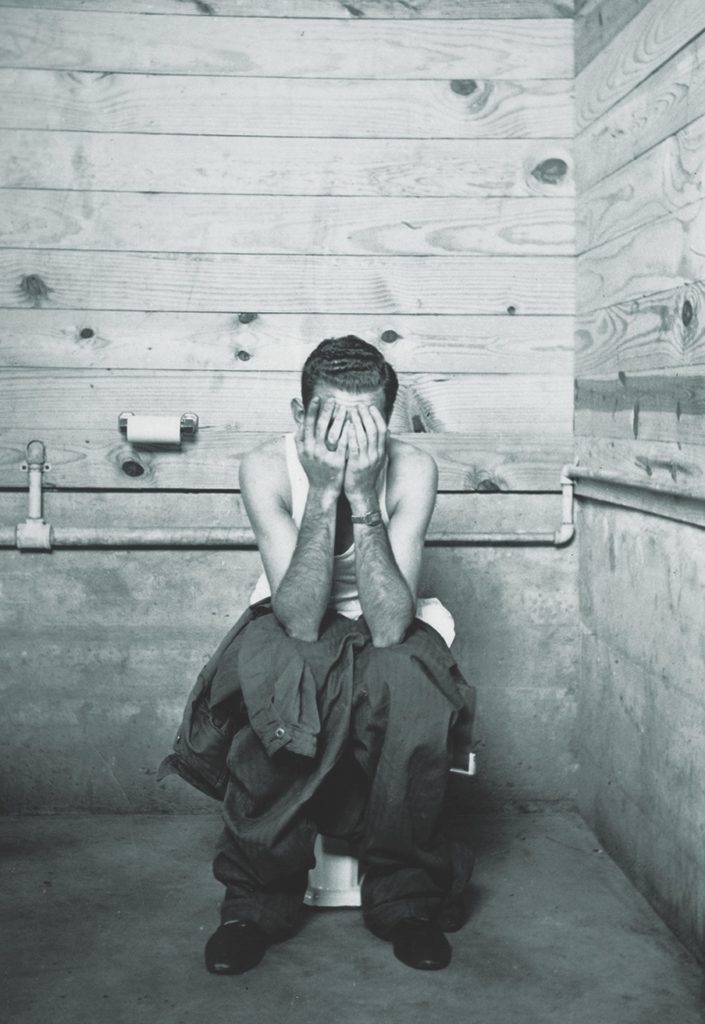

THE REGULAR ARMY was an education. A really rough education. I’d never gone to the toilet before with 16 other guys sitting next to me. I would go crazy waiting for the latrine to be free of people so I could rush in, do my stuff, and rush out. It took a lot of getting used to.

Sitting with 12 other guys having breakfast was another new experience. Everything was “Pass the butter! Pass the milk! Pass the sugar! Pass the jam!” There was a strict code. When somebody said, “Pass the jam,” you weren’t allowed to stop the jam and put any on your own plate. That was called “shortcutting” and was not allowed. You had to pass the jam to the person who said “Pass the jam,” even though the jam looked good, and you wanted to take a little on the way. It was forbidden.

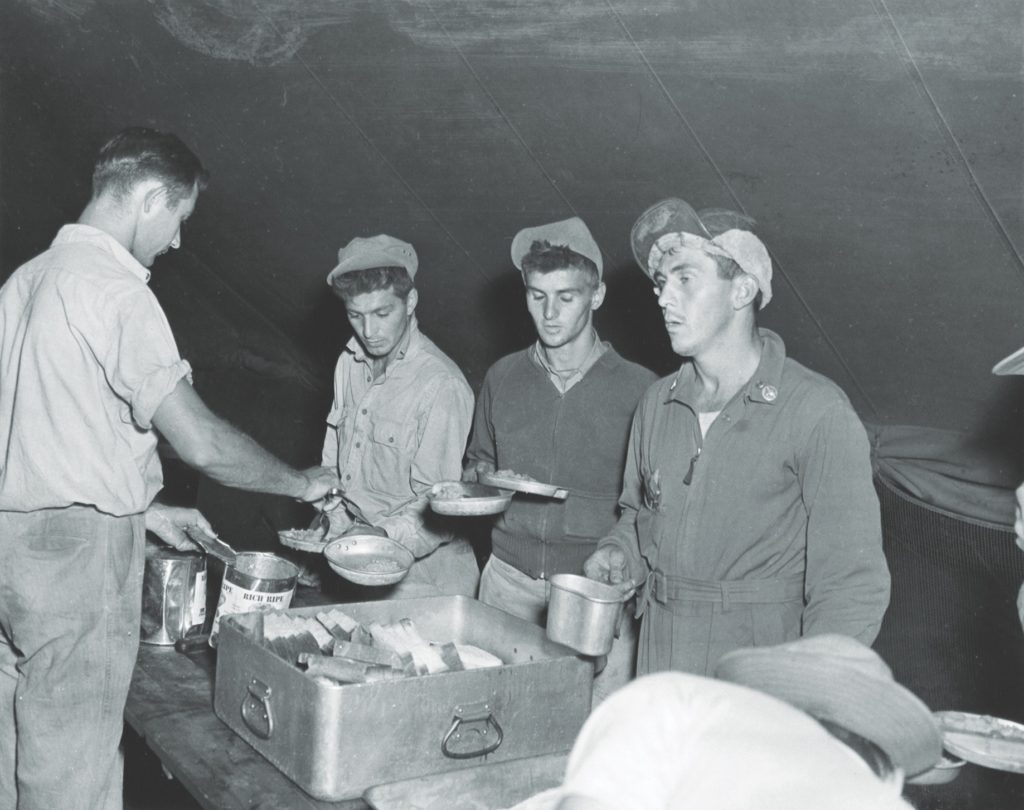

When we were on bivouac—a temporary campsite away from the barracks—we’d stand in the chow line with our mess kits. Mess kits were two small oval aluminum trays with indentations for food and an aluminum knife, fork, and spoon attached. You waited with your mess kit, and they’d throw some beef stew in one of the indentations. Then came the mashed potatoes, and even though there were other indentations for the mashed potatoes they always threw it right on top of the stew. Then—you won’t believe this—for dessert there were usually sliced peaches. Which of course, you expected they would put into one of the remaining empty places in the mess kit. But what did they do? They hurled it right on top of your potatoes and beef stew. They simply didn’t care. And we were starving so we gobbled it down. (For some reason, to this day I’m vaguely nostalgic for some sliced peaches on top of my beef bourguignon.)

After chow, you waited in line once again to clean your mess kit. First you swirled it around in a garbage can bubbling with hot soapy water. Then you moved it to the next garbage can of rinse water, still filled with the remnants of soap. And then the last garbage can with clear hot water. That did the job. It never occurred to me to ask my sergeants and officers: Why do we have to do all this stuff? Isn’t there a better way? Couldn’t we have a little more time for reading a book we liked, or maybe taking a nap once in a while? And then I realized: That’s why the army likes 18-year-olds. No questions asked. You do what you’re told.

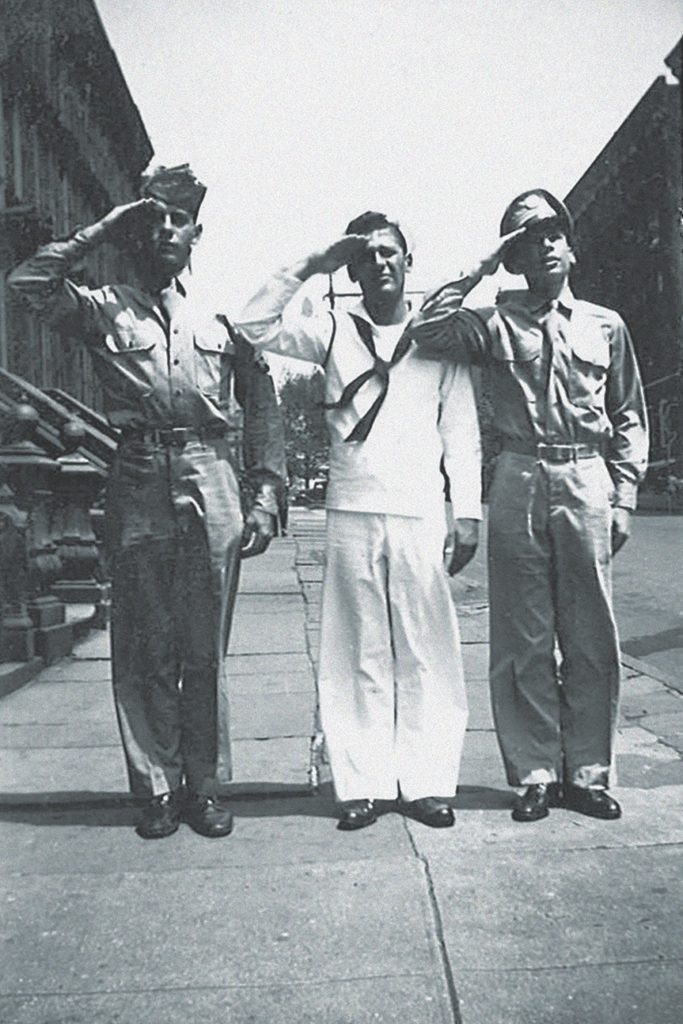

When I finished basic training at Fort Sill, I was shipped back to Fort Dix for overseas assignment. I was lucky to get a weekend in New York so I could see my mom, my grandma, my aunts and uncles, and the few friends who were also in the service but hadn’t shipped out yet. I stuffed as much of my mom’s delicious food as possible down my gullet. She made me things I loved like matzo ball soup, potato pancakes, and stuffed cabbage—things I knew were hardly ever served on an army chow line.

Recommended for you

Seasick and sleepless

AND THEN ONE NIGHT—I think it was around February 15 or 16, 1945—together with three or four hundred other guys, I boarded a troop transport at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, the SS Sea Owl. I remember going down below to the third or fourth deck, and I was greeted with the sight of rows and rows of stacked metal bunks. Each row was six beds high. It looked like hundreds of bunks. Unfortunately, in my row I got the third one, which was right square in the middle of the stack with what looked like a 200-pound G.I. above me.

Things were fine until the ship got to the open sea. Nobody told me about the North Atlantic in February. Huge waves slammed us from side to side and then, like a corkscrew, moved us way up and plunged us way down. And I realized there was no way to stop it.

Soon the throwing up began. It quickly became a cacophony of puking that never stopped. I was strong and brave for about eight days, but then I could no longer take sleeping down in the incredible stench that permeated the lower deck. Not only were we weathering a stormy North Atlantic in late February, we were also zigzagging every few miles to avoid German U-boats.

It occurred to me that even though the sinkings of Allied ships were getting dramatically lower in early 1945, there was still the bad-luck chance of a U-boat deciding to sink our troopship. So I decided to take my chances sleeping on the top deck. With $20, I bribed a merchant marine sailor to let me put my sleeping bag under a lifeboat, and he was nice enough to give me some all-weather tarps to cover me against the sea spray. It was rough up on deck, but so much better, both smell-wise and torpedo-wise, than sleeping down below.

Reassigned again

Fortunately I only had to do it for two nights, for on the third night, there it was—the rugged coast of France. Soon we were moored at the port of Le Havre. But even though I was sent overseas as a radio operator in the field artillery, the army once again decided that I should be something else. This time it was a combat engineer. The army moved men to various units as needed; I was transferred with some of my shipmates to the 1104th Engineer Combat Battalion. We were put on long troop transport trucks and sent further inland in Normandy for combat engineer training. Small groups of men were deposited at different villages.

Eight men, including me, got off at a little farmhouse with a sign on the entrance that said “Mon Repos.” It occurred to me that Mon Repos—“My Repose”—was a rather grandiose name for, maybe, the summer home of a retired nobleman. But it turned out to be just a country farmhouse. It was in the village of Saint-Aubin-sur-Scie. The village was near a larger town called Offranville, not far from the fairly big and busy port of Dieppe on the English Channel.

We were taught to safely unearth land mines. Some of them were big, and some of them were smaller. The big ones were called Teller mines. They carried a lot of explosives in them. You would have to probe the earth lightly with your bayonet and if you heard Tink! Tink! Tink! you knew there was something dangerous underneath. You had to be very careful. So you would clear away the dirt and then ask the help of the one guy in your platoon who was an expert at defusing mines—who really knew what and where all the wires were. He would take out a whisk broom and lightly dust away the earth surrounding the mine and proceed to disengage the fuse. I couldn’t really see exactly what he was doing, because we were a good 20 yards away hunkered down beneath our steel helmets. Lucky for me, our expert always defused them without a mistake.

Other land mines were trickier. They were set up with tripwires. Soldiers could be walking, hit the tripwire near them, and then you’d hear a click and an S-mine—a canister filled with all kinds of shrapnel nicknamed a “Bouncing Betty”—bounced up about chest high and, for a radius of 20 feet, destroyed anything around it. If you heard that click, you knew that the mine was in the air, and you hit the ground as quickly as you could and buried your face in the earth because it exploded in a conical manner. The closer you could get to the ground, the safer you were. Running was not an option.

We were also taught to search and clear unoccupied houses of booby traps. What’s a booby trap? Well, for instance, if you were sitting on the john and pulled the chain behind you, sometimes instead of the flushing sound you might hear a loud explosion and find yourself flying through the air. Which would mean that a booby trap had been positioned in the water closet above the toilet. So before troops could occupy a domicile, we had to be sure it was cleared of booby traps.

To this day, even though I’m not a soldier and I’m not in Germany and I’m not in a war, if I enter a toilet with a pull chain behind the commode, I have a tendency to stand on the bathroom seat and peer into the tank above to see if there is a booby trap—which hardly makes any sense in a restaurant in New York. Needless to say, I never saw any, but I still breathe a sigh of relief every time I look in and just see water.

In addition to clearing mines, combat engineers were taught to build makeshift structures to span small rivers or creeks. They were called Bailey bridges. It’s like a giant erector set: the bridge is constructed on one side of a river or a creek, and then swung over the water and dropped down on the other side. They were light, practical, and strong enough to support the weight of 6×6 trucks or even a Grant or a Sherman tank.

When our training in Normandy was over, we boarded more 6×6 trucks and made our way through Belgium down to France’s Alsace-Lorraine region, on the German border. I was lucky to get through Belgium on my way to Germany a couple of months after the Battle of the Bulge. Had I been born six months earlier, I probably would have been fighting in that and who knows what would have happened? Anyway, luck was with me, the Germans were finally in retreat, and life got a little better and a little safer.

fortune favors the brave

We were stationed in the German city of Saarbrücken, right on the border with France. The 1104th Combat Battalion was attached to the Seventh Army. Our job was to use our combat engineer training in land mine and booby trap detection to clear the dwellings in newly captured territories. It was hard work, not to mention scary work, but we went over everything with a fine-toothed comb.

One day I was out on patrol with my platoon and we found a case of German Mauser rifles near an old railway siding. They were beautiful sharpshooting rifles with bolt action. Sure enough, there was a box of ammunition right next to them. So we had a contest. There were these white ceramic insulation things up on the telephone poles, and any man who shot one down won a dollar from each of the others. I was pretty good at that, and I’d made about $21 when suddenly we got a strange call on our command car radio: “Get back to the base immediately!”

When we arrived back to our base there was a lot going on. Platoons of men were moving rapidly all over the place. My company commander told us that army communications had been severed. It seems that some telephone and telegraph wires had been destroyed. Uh-oh!

I quickly realized that we were the destroyers. Those white ceramic insulators were the wrong things to make a target-practice game of. So knowing that we were really not in danger, I gallantly offered to take my men out again and search for the enemy snipers that had sabotaged the phone lines. My company commander gave me permission and sent us off with a salute that connoted something like, “You men are a brave bunch.” We never let on.

‘Is there anybody who can tell a joke?’

IT WAS THE BEGINNING of May 1945, and it looked like the war in Europe was rapidly coming to a close. My unit was then stationed in a German town called Baumholder, in the southwest part of Germany. We occupied a small German schoolhouse. There was a fellow soldier with me named Richard Goldman, who later became a well-known tax lawyer. He had been with me on the boat coming over, with me when we were transferred from the artillery to the combat engineers, and generally slogged through the mud by my side as we tried to stay alive during the war. Richard was very smart. A lot smarter than I was. Because on V-E Day, that glorious day that the war ended in Europe, he marched me down to the cellar of the schoolhouse and showed me some K rations and a bottle of wine that he had procured for us.

I said, “Dick, what’s this all about?”

He said, “Even though the shooting ended today, tomorrow is the official announcement of V-E Day. Everyone will go crazy. They will be joyously firing their weapons into the air. No one in that state of euphoria will realize that what goes up must come down, and the bullets will surely come raining down on what’s below. So that’s why we are going to spend the next 24 hours in this cellar, trading the joy of victory for the tired cliché of just staying alive.”

So thanks to the savvy thinking of Richard Goldman, I’m still here.

The war was over, but I didn’t go back to America immediately. We became part of the Army of Occupation. It was much safer, but kind of dull.

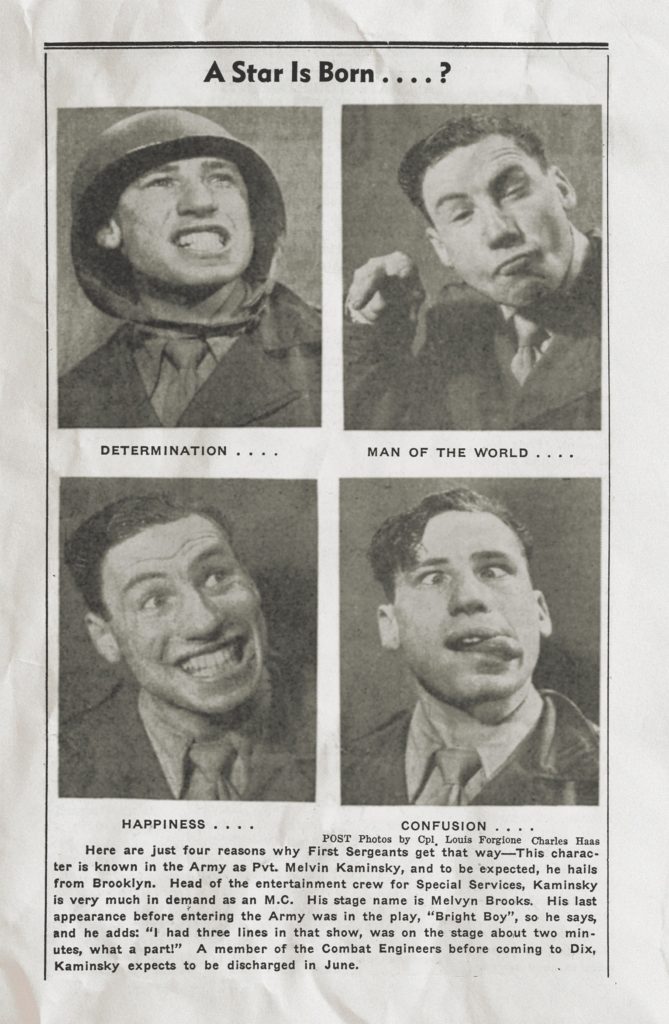

One day, a lieutenant from Special Services who was touring army installations in our area said, “Is there anybody in this unit who can sing? Dance? Tell a joke or play an instrument?”

I immediately raised my hand. He said, “What can you do?”

I said, “All of the above! I can sing, dance, tell jokes, and play the drums.” I told him all about what I had done from age 14 on in the Borscht Belt—an affectionate term for the area of the Catskill Mountains about 90 miles north of New York City replete with Jewish summer resorts—where I’d discovered I was a comedian. He asked my CO if he could borrow me for a few weeks. So I joined his Special Services unit and became one of the comics in a variety show touring different army camps. Needless to say, I was an exceptional addition to his staff. As a result, the lieutenant asked my CO if he could permanently transfer me to Special Services. Permission was granted, and I was an entertainer once again.

I reported to Special Services in Wiesbaden, Germany. I was made an acting corporal and put in charge of the entertainment at non-com and officers’ clubs. It was a great gig. I was busy putting together German civilian talent with American G.I.s who could sing, dance, and play instruments for variety shows that I would MC. I was almost disappointed when I was told my time in Europe was up and I would be going back to the USA.

The journey back to America in April 1946 was a lot faster and safer than the journey to Europe. We were on the Queen Elizabeth, a beautiful boat and a big step up from the Sea Owl. It was seven or eight in the morning when we entered New York Harbor. At the sight of the Statue of Liberty smiling down at us, many a G.I. broke into tears. I think I was one of them.

I was sent to Fort Dix for a month or two before processing my reentry into civilian life. I did some camp shows with Special Services while there. I exercised my songwriting skills by writing parodies. For instance, instead of Cole Porter’s “Begin the Beguine,” we’d sing, “When we begin to clean the latrine.” And for “The Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy of Company B” we rolled up our pants legs and became the Andrews Sisters.

I was discharged—honorably, I might add— in June 1946. Being a civilian once again was wonderful and terrible. I didn’t have to eat in a mess hall anymore; I could eat Chinese, Italian, or deli anytime I wanted to. But what to wear? In the army it was easy. You put on the same clothes every day. But I had actually grown about an inch and put on about 20 pounds while I was overseas, so I had to get a whole new wardrobe. My favorite wing-tipped black-and-white shoes were heartbreakingly too small to wear anymore. I had grown up.

The army didn’t rob me of my youth; it really gave me quite an education. If you don’t get killed in the army, you can learn a lot. You learn how to stand on your own two feet. ✯

From the book ALL ABOUT ME! My Remarkable Life in Show Business by Mel Brooks, published by Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2021 by Mel Brooks.