The common image of the U.S. Marine Corps in Vietnam is a scene with Leathernecks on the ground, holding off—and beating back—a larger enemy force. But Marines in Southeast Asia who fought their country’s battles did so, as the Corps’ hymn states, not only “on land and sea” but also “in the air.”

Marine aviators in Vietnam continued a legacy that stretches back to the birth of aerial combat. During World War I, Marine 2nd Lt. Ralph Talbot and Gunnery Sgt. Robert G. Robinson, returning from a bombing mission over Flanders in a Liberty D.H. 4 biplane, fought their way through a dozen German Fokker D.VII fighters on Oct. 14, 1918, and were both rewarded with the Medal of Honor. Less successful was 2nd Lt. Charles F. Nash, who flew Spad XIII fighters while on detached duty with the U.S. Army Air Service’s 93rd Aero Squadron until he was shot down and taken prisoner by Leutnant Fritz Gewert of Jagdstaffel 19 on Sept. 13, 1918.

The next world war was the one where Marine fighter pilots really showed their stuff and set an example for those aviators who would follow. From their heroic defense of Wake Island through the Solomon Islands campaign and their participation in the Battle of Okinawa from both land bases and aircraft carriers, Marine dogfighters in World War II distinguished themselves against Japanese forces.

Joseph J. Foss, the Marine ace-of-aces with 26 victories, received the Medal of Honor, as did aces (with shootdowns ranging from nine to 25) Robert M. Hanson, Gregory Boyington, Kenneth A. Walsh, John Lucian Smith, James E. Swett, Harold W. Bauer, Robert E. Galer and Jefferson J. DeBlanc. Another World War II Medal of Honor went to Marine Capt. Henry T. Elrod, credited with destroying two Japanese bombers and sinking the destroyer Kisaragi. When his F4F-3 Wildcat and all other U.S. aircraft on Wake Island were disabled, Elrod fought on the ground until he was killed on Dec. 23, 1941.

In subsequent wars, Marine aviation missions were focused on airstrikes against enemy ground forces or fire support for U.S. ground forces rather than on aerial combat against enemy planes. Marine aviators who were fighter pilots generally flew with other services, typically the Air Force.

During the Korean War, Maj. John F. Bolt, already a six-victory World War II ace, flew F-86F Sabre jets with the Air Force’s 51st Fighter Interceptor Wing in mid-1953 and added six Chinese MiG-15s to his score. Another Marine exchange pilot in the same Air Force unit, Maj. John Glenn, was credited with three victories—and went on to greater fame in 1962 as the first American astronaut to orbit the Earth.

In the Vietnam War, as in Korea, most Marine pilots were engaged in attacks on ground targets, even those aviators who flew in the versatile F-4 Phantom II fighter-bomber. Nevertheless, a few Marines got the chance to match wits and trade missiles with MiG pilots.

Their first encounter with the enemy occurred on Dec. 17, 1967, at the height of Operation Rolling Thunder, President Lyndon B. Johnson’s March 1965-October 1968 bombing campaign against North Vietnam. That day 32 Air Force F-105D Thunderchief fighter-bombers and their Phantom escorts were en route to bomb the Lang Lao railroad bridge west of Hanoi when they were attacked by three MiG-21s of the North Vietnamese air force’s 921st Fighter Regiment, which scattered the bombers and claimed three shot down.

The Americans actually lost only one, an F-4D of the 497th Tactical Fighter Squadron, 8th Tactical Fighter Wing. Its Air Force crewmen, Maj. Kenneth R. Fleenor and 1st Lt. Terry Lee Boyer, ejected and were taken prisoner. They were not released until March 14, 1973, after the war had ended for American forces.

Meanwhile, four MiG-17s of the 923rd Regiment took off from Hanoi’s Gia Lam airfield with orders to hit American aircraft reported west of Hanoi. Ten minutes later, at an altitude of 11,500 feet, pilot Luu Huy Chao spotted four Phantoms approaching Yen Bai airfield in the north-central part of North Vietnam. Pushing his MiG to maximum speed, he got onto the tail of one Phantom, fired three bursts of 37 mm and 23 mm cannon fire and saw the fighter go down.

The other three MiG-17s swept through the American formation. Bui Van Suu fired three bursts at his target and reported that he saw that Phantom going down to a crash. Le Hai also fired three bursts, striking the fuselage and right wing of his quarry, although failing to kill it. But the fourth MiG, flown by Nguyen Hong Thai, was missing, Chao reported.

What happened to Thai? He had been shot down and killed by an F-4D Phantom II of the Air Force’s 13th Tactical Fighter Squadron, 432nd Tactical Reconnaissance Wing. The F-4D’s pilot was Marine Capt. Doyle D. Baker, on exchange duty with the squadron. The other crewman was Air Force 1st Lt. John D. Ryan Jr., a qualified pilot riding this time in the Phantom’s back seat as the weapons systems operator.

It would be almost five years before Marines mixed it up again with the North Vietnamese air force—under much different circumstances. In April 1972, the North Vietnamese Army launched an invasion of South Vietnam, and President Richard Nixon responded with the second major U.S. bombing campaign of the war, Operation Linebacker I, May-October 1972.

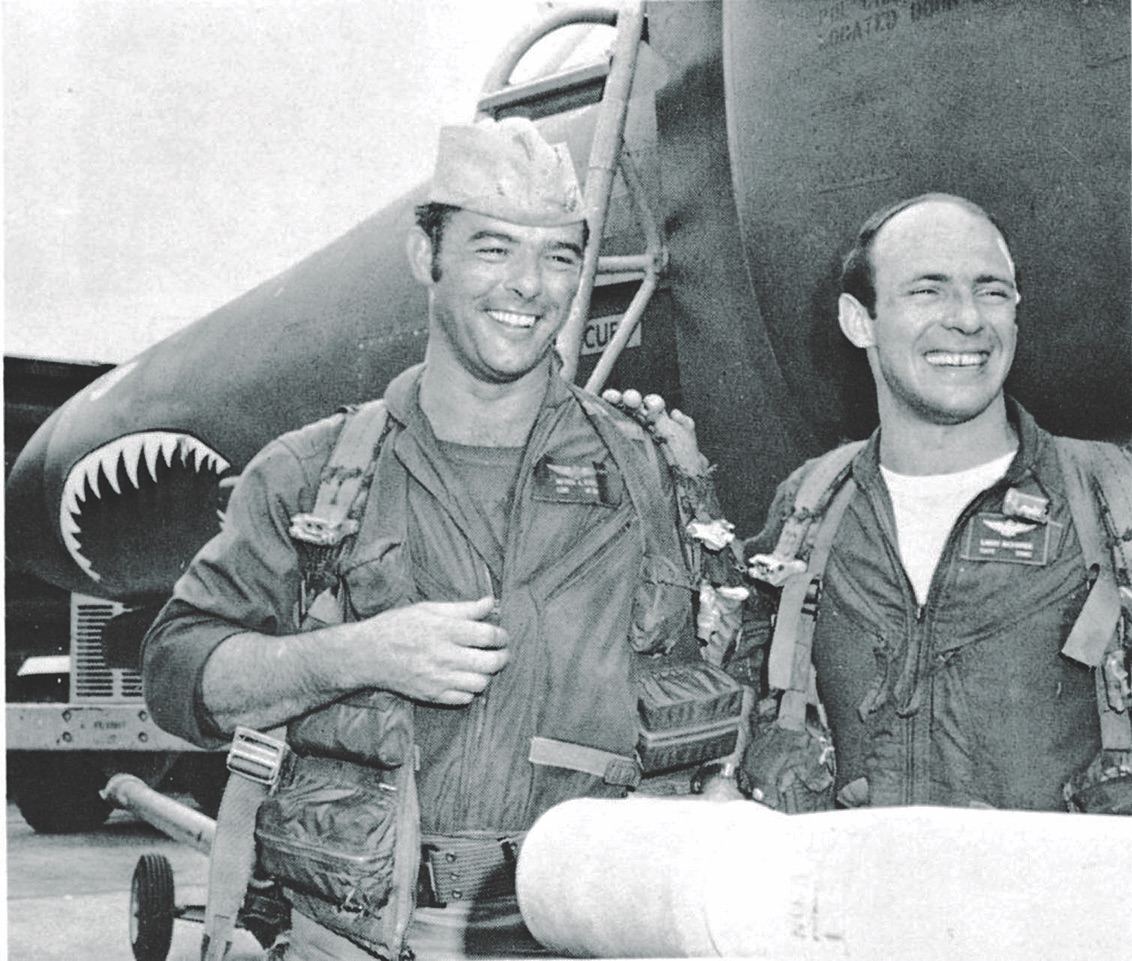

On Aug. 12, 1972, five Phantoms of the 58th Tactical Fighter Squadron, 432nd Tactical Reconnaissance Wing, took off from Udorn Royal Thai Air Base on a flight to determine if weather conditions were right for a bombing strike in North Vietnam. Leading the flight in an F-4E, whose armament included the first 20 mm cannon built into the Phantom, was Marine Capt. Lawrence G. Richard. At his right wing was an RF-4C Phantom reconnaissance plane. The other three aircraft were F-4Es.

Richard was on exchange duty with the Air Force. “We deployed to Udorn for six months under what was termed the ‘Summer Help Program,’ when the forces of Thailand were bolstered up in the summer of 1972,” he said.

Richard’s weapons systems operator, Navy Lt. Cmdr. Michael J. Ettel, had worked in the Air Force’s 10th Weather Squadron, which had closed down. “He was left without a job,” Richard explained, “so he went around to the various squadrons hoping to get assigned. Our squadron agreed to fly him in the back seat until he got current in the airplane, and he flew with me most of the time until he qualified as aircraft commander. That worked out real well, since we were both on exchange duty with the Air Force.”

Richard and his flight were over North Vietnam’s Red River, 60 or 70 miles west of Hanoi, when their headquarters radioed that enemy fighters were “at your six o’clock [rear], 30 miles, and attacking!” Richard led his flight south until he spotted the MiGs 4 miles away, traveling at supersonic speed. “The lead MiG-21 was silver, and his wingman was a mottled green camouflage…a really pretty airplane,” Richard recalled. “I called tallyho, and we blew off our wing tanks, as my element began a slice turn down into their inside.”

With two F-4Es climbing to guard his tail, Richard followed the MiGs into a slow left turn until he got a radar lock on the leader and fired a radar-guided AIM-7E-2 Sparrow missile about 1½ miles from the MiG. The missile was halfway to its target when the North Vietnamese flight leader apparently spotted it and suddenly turned toward his attacker. The AIM-7 went over the enemy fighter’s cockpit without exploding. “He passed me, canopy to canopy, no more than a couple hundred feet away,” Richard said, “rolled around my six and dove out of sight.”

Turning his attention to the second MiG, Richard fired another Sparrow. It struck just ahead of his target’s tail, which broke off and sent the MiG falling in a vertical spin. “One of the funny aspects of the mission was that the recce [reconnaissance] pilot on my wing had no idea that we were going to engage the MiGs,” Richard said. “When we turned around, he thought we were just smoking for home…. Until he saw the Sparrows come off my airplane, he didn’t know we were in a fight.”

August was not a good month for the North Vietnamese air force, which lost four MiG-21s and two pilots. The only communist success came on Aug. 26 when Nguyen Duc Soat and Le Van Kien of 3rd Company, 927th Fighter Regiment, spotted two Phantoms about 9 miles from the Laotian border. Soat fired an R-3S missile that went up the right engine of one Phantom and blew it out of the sky. Soat was one of North Vietnam’s rare undisputed aces: All six of his shootdowns can be traced to corresponding American losses.

Soat’s victims on Aug. 26 were 1st Lts. Sam Gary Cordova and Darrell L. Borders of Marine Fighter Attack Squadron VMFA-232, Marine Aircraft Group 15, the only Marines shot down over Indochina in air-to-air combat. Their plane, one of two that took off from Nam Phong, Thailand, exploded in flames over eastern Laos.

Both men ejected, and Borders was quickly rescued. Cordova, using his survival radio, said he was coming down in a ravine and enemy pursuers were approaching. Heavy groundfire from the nearby Viet Cong-controlled Laotian village of Ban Na Ca Tay prevented the rescue helicopters from reaching the Marine. Cordova’s fate was unknown for decades until Vietnam found his remains and returned them to the United States on Dec. 15, 1988. Their identity was confirmed in March 1989.

On Sept. 11, 1972, the Marines got even with a counterblow to the North Vietnamese fighter force. And this time the Leathernecks flew a mission run entirely with Marine aircraft and crews. Four F-4J Phantoms of VMFA-333, which had been operating from the carrier USS America since July 14, were on a combat air patrol looking for potential enemy activity northeast of the major North Vietnamese port facilities at Haiphong Harbor.

Leading the Marine aviators was the squadron’s executive officer, Lt. Col. Lee T. “Bear” Lasseter, who had helped establish the Marine Aviation Weapons and Tactics Squadron at Yuma, Arizona, which taught air combat maneuvering tactics much like those developed for the Navy’s Topgun program at Miramar Naval Air Station, California. His crews flying toward Haiphong had received similar training.

Lasseter also made sure the technology of his F-4s was ready for the fight. The squadron’s AWG-10 search and track radars, which guided AIM-7 and AIM-9 missiles, were among the most reliable in the combat zone, thanks to the efforts of Capt. John D. “Li’l John” Cummings, who rode in Lasseter’s plane as radar intercept officer, responsible for the aircraft’s weapons systems.

Prospects for action looked good. Earlier in the day on Sept. 11, an Air Force bombing strike on Hanoi brought two MiG-21s of the 927th Fighter Regiment scrambling from Hanoi’s Noi Bai airfield to intercept four Phantoms that were dropping radar-confusing metal chaff near Kep airfield, northeast of the city. Le Thanh Dao shot down the F-4E of Air Force Capts. Brian M. Ratzlaff and Jerome D. Heeren of the 335th Tactical Fighter Squadron, 4th Tactical Fighter Wing. Both ejected and were taken prisoner. They were released on March 29, 1973.

In the late afternoon, Lasseter’s flight was alerted that MiGs were circling Phuc Yen airfield near Hanoi. When Cummings picked them up on his radar, the MiGs were 19 miles away. At 6 miles distance Lasseter’s wingman, Capt. Andrew Scott Dudley, spotted a silver MiG-21 at low altitude. The chase was on.

The Marines’ target, identified after the war, was an unarmed MiG-21U trainer of the 921st Fighter Regiment with a Soviet adviser, Vasily Motlov, in the back seat. He and North Vietnamese pilot Dinh Ton were returning from a combat training flight when radar crews on the ground warned that four Phantoms were lurking about 5 miles from Noi Bai.

Soon afterward, Lasseter launched two AIM-7E-2 Sparrow missiles, but Motlov evaded them with fancy maneuvering. A wild dogfight ensued over Phuc Yen, while anti-aircraft artillery took potshots at the Americans. Lasseter got two more Sparrows off but missed again. He then fired two AIM-9D heat-seeking Sidewinder missiles, which the MiG likewise evaded.

At that point Dudley, his fuel low, disengaged. Coincidentally, Motlov noticed his MiG was down to 100 liters (22 gallons)—not enough to return to Phuc Yen. He ordered Ton to eject. To prepare for the ejection, Motlov reversed direction and put his MiG into a steep climb, only to feel his engine flame out at about 1,600 feet of altitude. Moments later Lasseter, with two AIM-9s still in his quiver, fired one at his frustratingly elusive adversary.

“The growl of the Sidewinder tone was loud enough to drive you from the cockpit,” Cummings said later in an interview, “and it really did a job on that MiG. Everything aft of the cockpit was gone.” But Ton and Motlov had escaped the blast. They ejected just before the missile struck and landed safely.

Lasseter then saw what appeared to be a black MiG-21 going for Dudley’s Phantom. Launching his last Sidewinder, he saw it guide into the MiG, which dived away trailing smoke—possibly hit, but not a confirmed shootdown. Even with no more MiG fighters around, Lasseter and Dudley still had to deal with the two other weapons in the triad of North Vietnam’s air defense system: surface-to-air missiles and anti-aircraft artillery.

As they made a beeline for their carrier and flew over Hanoi, an SA-2 SAM exploded near Lasseter’s right wing. Although he regained control, the best the squadron commander could do was get his stricken plane as far out to sea as possible before it died, at which point he and Cummings ejected. Minutes later anti-aircraft guns hit Dudley’s Phantom, causing the fuel to drain out. Like their colleagues, Dudley and his radio intercept officer, 1st Lt. James W. Brady, performed a “feet wet” ejection over the Gulf of Tonkin.

Though the two Phantoms ended up in the drink, at least they had cleared the enemy coast so that search and rescue units could retrieve all four crewmen floating in the sea. Safely aboard the America, they celebrated the first—and only—“all-Marine” aerial victory over Vietnam in the shootdown of Motlov’s MiG, as well as the probable damage inflicted on the “black” MiG-21. Lasseter was awarded the Silver Star for his actions that day.

Thus, the Marine fighters’ final tally for the war was three shootdowns—by Baker (with Ryan of the Air Force) on Dec. 17, 1967; Richard (with Navy man Ettel) on Aug. 12, 1972; and the Lasseter-Cummings team on Sept. 11, 1972. One Marine, Cordova, died sometime after being shot down on Aug. 26, 1972.

After Vietnam, the Marines reverted to their usual ground attack role—for the most part. One more exception arose during the 1991 Gulf War, when a Marine pilot was again on exchange duty in an Air Force squadron.

On Jan. 17, 1991, the first day of combat in the war against Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein’s forces, Americans launched an air offensive to clear the sky over Iraq. In that engagement Air Force Capt. John J.B. Kelk, flying an F-15C Eagle in the 58th Tactical Fighter Squadron, 33rd Tactical Fighter Wing, shot down a MiG-29 for the first aerial victory of the war.

Later in the mission, Marine F-15 pilot Capt. Charles Magill, a graduate of the Topgun program attached to the 58th TFS, led a squadron that spotted two MiG-29s west of Baghdad. After Air Force Capt. Rhory Draeger blasted one of them, Magill fired a Sparrow missile, followed by another. But the first one did the job, destroying the second MiG.

Back at the 58th’s temporary accommodations at King Faisal Air Base in Saudi Arabia, Magill proudly applied a green star under the cockpit of his Eagle. Given the paucity of aerial opposition during the decades since that unequal clash over Iraq, Magill’s action may well have marked the end of an era for Marine Air…pending further notice, of course…

Jon Guttman is research director of Vietnam magazine.

This article appeared in October 2019 issue of Vietnam magazine.