If you’re an American who has ever indulged in a hot, delectable, creamy, comforting side of macaroni and cheese, you can thank the slave of a Founding Father for bringing the dish to America.

While historians cite the 13th century Italian cookbook “Liber de Coquina” as the first written and recognized macaroni and cheese recipe — a dish called de lasanis — the classic American side item arrived by way of France — courtesy of James Hemings.

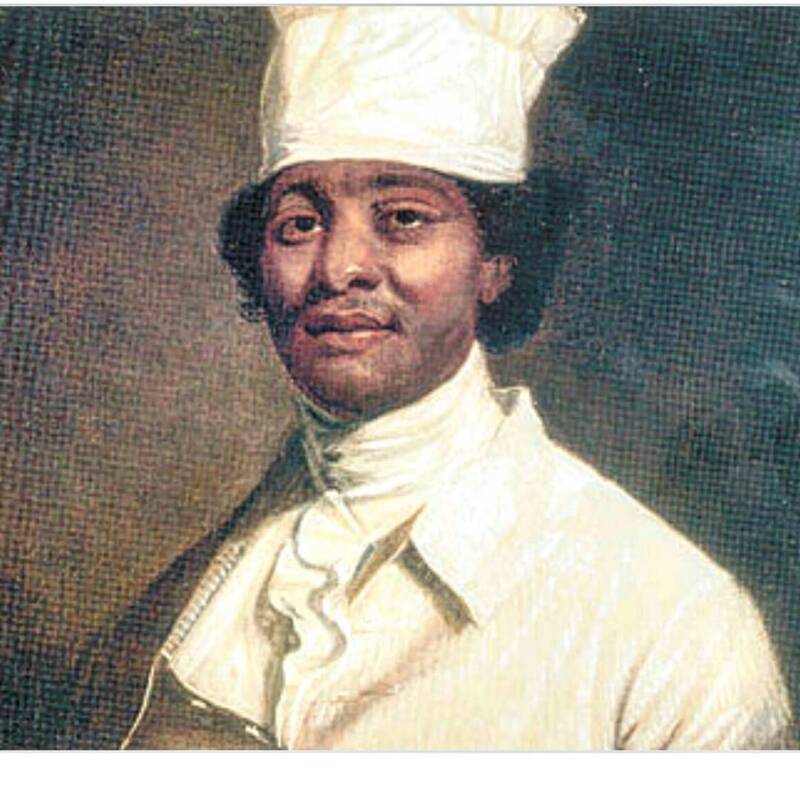

Born in 1765, Hemings was the sixth child born to Elizabeth Hemings, an enslaved woman, and owner John Wayles. Wayles, the father-in-law of Thomas Jefferson, fathered six of Hemings’ children — making them half brothers and sisters of Jefferson’s wife, Martha, according to Monticello Magazine.

Upon Jefferson’s marriage to Martha, Hemings and his siblings —including Sally Hemings — became property of the Founding Father to be.

Not only could Hemings read and write — a rarity for the times — he was also an accomplished chef.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

So, when Jefferson was appointed Minister to France from 1784 to 1789, the notorious Francophile and “foodie” brought along the 19-year-old Hemings with the intention of having him train among the Parisian elite.

According to the White House Historical Association, “French chefs were very expensive to employ, and Jefferson’s costs regularly outpaced his income. While Jefferson may have been short on cash, he did have an abundant supply of readily available enslaved labor, bound to serve him for life. To save money, Jefferson employed French chefs to train several enslaved members of the Monticello community in the delicate art of French cookery.”

This included, of course, what we now consider mac and cheese.

From Italy to the rest of Western Europe, the widespread culinary exchange happening in courts throughout Europe at the time morphed the Italian dish into an altered version that made its way to England, called macrows, and France. It’s disputed whether Jefferson first discovered the creamy pasta dish in Italy or France, but what isn’t under dispute is his love for it.

In 1807, Jefferson purchased 80 pounds of parmesan cheese and 60 pounds of Naples-based macaroni. His last grocery order, placed five months before his death in 1826, included “Maccaroni 112 ¾ lb,” according to EatingWell. (Despite such large quantities of simple carbohydrates and dairy, Jefferson did not, in fact, die of a heart attack. He did, however, contract a nasty infection on his buttocks which most likely developed into septicemia, causing his death.)

As Jefferson’s primary chef, Hemings is certain to have mastered the perfect balance of butter, cheese and macaroni.

During his time in France, Hemings apprenticed with a caterer, a pastry chef and even as a chef for the prince de Conde.

“For an American to go and learn that … was pretty incredible,” food historian Paula Marcoux — who has recreated classic French dishes of the era at Monticello, using the same types of cooking tools Hemings would have used — told NPR.

In 1787, Hemings was appointed chef de cuisine at Jefferson’s home in Paris, supervising white servants in the kitchen among other duties. And, in 1789, despite finding out that under French law, he was a free man, Hemings elected to return to Virginia with Jefferson, enslaved.

“Family,” historian Annette Gordon-Reed told NPR. “There was a real dilemma for many enslaved people: Do you take your freedom and separate yourself from your family?”

Hemings continued in his position as an enslaved chef under Jefferson, moving to New York and Philadelphia with the latter as he served as the secretary of state under President George Washington.

In 1793, however, Hemings successfully bargained for his freedom — with a caveat.

“Hemings would return to Monticello to train another enslaved person in French cooking to serve as a replacement chef. Once the replacement chef was properly trained, Jefferson agreed that Hemings ‘shall be thereupon made free, and I will thereupon execute all proper instruments to make him free,’” according to the White House Historical Association.

Hemings began training his brother, Peter Hemings, but it would be three long years until Jefferson assented to James’ freedom.

In the 1796 deed of manumission, Jefferson wrote, “I Thomas Jefferson of Monticello aforesaid do emancipate, manumit and make free James Hemings, son of Betty Hemings, which said James is now of the age of thirty years so that in the future he shall be free and of free condition, and discharged of all duties and claims of servitude whatsoever, and shall have all the rights and privileges of a freedman.”

Of the 607 men and women Jefferson owned during his lifetime, according to Susan Stein, senior curator at Monticello, only two had ever negotiated for their freedom. James Hemings was one of them.

Only several years after finding his freedom, Hemings tragically died by suicide in 1801.

While he left no memoirs, he did leave his recipes. And America — although not our cholesterol levels — is better for them.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.