Pesident Abraham Lincoln’s grand review of the Army of the Potomac on April 9, 1863, would be remembered fondly by both awed onlookers and the regiments that paraded before him at Belle Plaine, Va. In many ways, the occasion marked the end of what had been a very troubled winter following the Battle of Fredericksburg—what one Union soldier had called his army’s “Valley Forge.”

The men’s morale was on the upswing, and new commander Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, who in just nine weeks had done much to refit and prepare the Union’s principal army, was happy to show them off. As the third summer of the war approached, December’s Fredericksburg disaster and the woeful Mud March of January seemed like distant memories.

Although the entire review was impressive, it was the crisply massed lines and steady step of the 1st Corps’ “Iron Brigade of the West” that brought the loudest murmur of approval and applause from the crowd, with some ladies reportedly fluttering their handkerchiefs as those regiments passed by.

The unit, adorned in their splendid black hats, was the army’s only all-Western infantry brigade, made up of the veteran 2nd, 6th, and 7th Wisconsin, the 19th Indiana, and the recently added 24th Michigan.

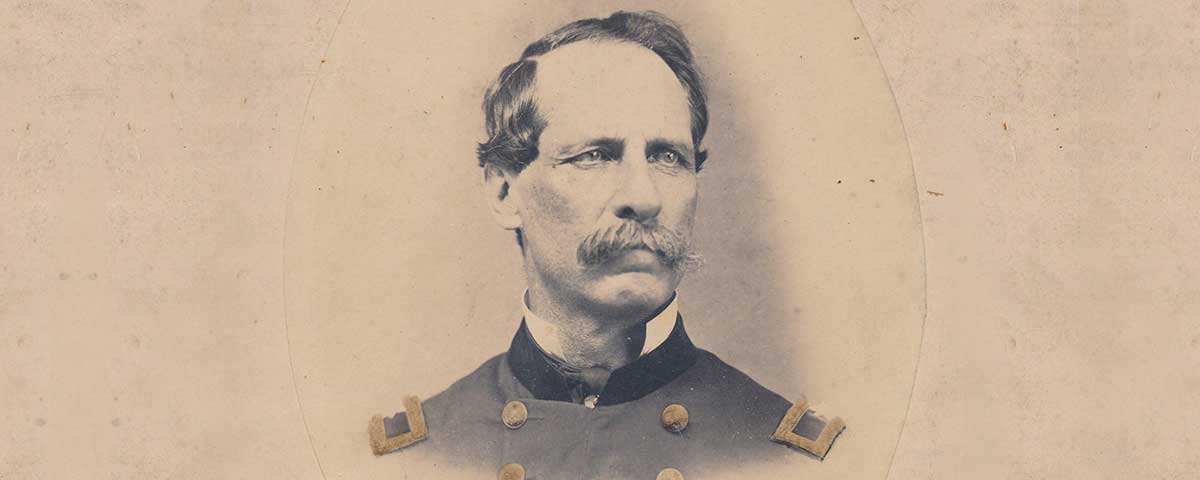

“This,” Hooker said, leaning close to the president, “is the famous fourth brigade.” Lincoln smiled and, as was his habit, quipped: “Yes. It is commanded by the only Quaker General I have in the army.” He nodded in the direction of Brig. Gen. Solomon Meredith of Indiana, impossible to miss at 6-foot-7, 250 pounds.

Recently promoted, Meredith had entered the war as the 19th Indiana’s colonel and had quickly become a great favorite of the men, who dubbed him “Long Sol” in deference to his imposing height. They enjoyed telling stories of his rustic mannerisms.[/quote]

Meredith was raised a Quaker in his native North Carolina. As a young man, he walked to Indiana to start a new life. He married well there, and prospered as a farmer and in politics. He was Wayne County clerk at the time of Fort Sumter in 1861 and was well known as a Republican political crony of powerful Indiana Governor Oliver P. Morton.

Always a man who caught eyes because of his height, Meredith had the loud and forceful voice of a stump speaker and was singled out for his colorful use of the English language. He was, a “specimen of the genuine Hoosier,” one of his soldiers wrote home, “who put on no airs and frequently talks to the private soldiers and is therefore very popular with the men but is not much of a military man.”

Another veteran said that Meredith took double the risk in battle, as he was twice as big as most men: “Stray scraps of iron running at large over the heads of a regiment are apt to pick out the tall ones.”

When Long Sol and his Indiana boys were added to the Midwestern brigade in October 1861, Meredith’s military abilities were questionable, but it was recognized that he had rock solid political connections. Wisconsin men said in solemn tones that Meredith and his regiment were “the pets” of Indiana Governor Morton. The volunteer Badger officers—many of them sharply attuned to the direction of the political winds—made note of the fact. A story circulated about how a political rival quipped that Long Sol was so tall that he should be cut in half and his lower, and better, half be made lieutenant colonel of the 19th.

The 19th Indiana left its home state for the front on two trains on August 5, 1861. The new colonel rode in the smaller second train and took along two of his favorite horses. At Harrisburg, Pa., the train halted so that 10 rounds of ammunition could be issued to each soldier in case of trouble at Baltimore where a Union regiment had earlier been fired upon while passing through the city.

No violence occurred, however, as they marched through the city to a connecting rail line. Back in the cars and bored, the ammunition in their cartridge boxes tempted the young Hoosiers to try out their muskets on “Rebel” ducks and chickens along the tracks. Soon the cars were ablaze with shooting and filled with smoke. At least one horse was shot dead.

Meredith, still much the farmer, was outraged at the slaughter of valuable livestock. He stormed through the cars demanding to know who was shooting. No one, of course, admitted to the deed.

At Washington, days wore into weeks, and weeks into months without action. The new volunteers—officers and privates alike—were learning to be soldiers. There was constant drill and some heavy labor constructing fortifications in Virginia beyond the Chain Bridge over the Potomac River.

Some excitement finally transpired on September 11 when five companies of the 19th Indiana, along with other detachments, tramped five miles into the countryside. Confederate cavalry soon attacked the reconnaissance force. The shooting lasted about two hours, and Meredith was proud to report that his Indiana companies “behaved with the utmost coolness and gallantry.”

In spring 1862, Army of the Potomac commander Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan devised a plan to move his force by water to Fort Monroe, from where it would advance on the Confederate capital of Richmond. The Western brigade soldiers were crestfallen to learn that they and the rest of Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell’s 1st Corps would not be part of the main campaign. They would be ordered only to occupy Fredericksburg, where they could be in a position to threaten Richmond and yet still protect Washington.

McDowell’s brigades moved from Washington by foot on April 4 in a march hampered by rain and snow. The columns reached Falmouth above Fredericksburg on April 23 and settled into a routine of work details, patrols, and drill.

Brigadier General Rufus King, the brigade’s first commander, had been promoted to a division post in late 1861, but it was not until May 8, 1862, that Captain John Gibbon of Battery B, 4th U.S. Artillery, which had been assigned to the brigade, was promoted to brigadier general of volunteers and given command of the Western regiments.

The change caused only a minor stir as the battery had been associated with the brigade for several months and some infantry volunteers had even been filling the depleted ranks in the battery. Gibbon’s tightening of discipline, however, was not greeted with enthusiasm. The new general was a Regular, after all, and the volunteers distrusted the Old Army manner.

No one was more upset than Colonel Sol Meredith, who had long made known his own ambition to win a star. He told anyone who would listen that volunteers should be commanded by volunteer officers, and then began writing letters to his powerful friends in Indiana and Washington to see what might be done.

Some of the Western regiments had marched off to war wearing gray militia uniforms, and even after the issue of the standard blue Union togs, some men still wore their old gray issues. Gibbon disliked the uneven appearance of his regiments, and required that the dark blue wool frock coats and black hats often issued to the Regulars be issued to all his men, along with white linen leggings and white cotton gloves.

The Midwesterners grumbled when it was discovered each soldier would pay for the gloves and leggings out of their clothing allowances. Gibbon’s order also called for extra underwear, stockings, and shoes. In making the requisition of his regiment, Meredith, aware of the displeasure in his ranks, slyly asked for four extra mule teams to transport the extra luggage. The request, of course, was denied, but Gibbon and Meredith were now at odds. Tensions escalated when the Indianans threw them away on the first long march and Gibbon sharply ordered they be reissued at additional cost.

One morning Gibbon emerged from his tent to find his horse equipped with four leggings. The breach of discipline upset the by-the-book Regular, who looked to the Indiana ranks to find the culprit without success.

A more troubling exchange erupted when Gibbon reviewed his brigade and issued a general order that singled out the “marked contrast” in appearance between the Wisconsin units and the 19th Indiana. The general also made a sour reference to the clothing discarded on recent marches, and stated that every soldier found without his issued clothing “will be charged the cost of such clothing…and have the amount deducted from his pay.”

The order set off a storm, especially in the 19th Indiana, where the leggings and the general were especially hated. Meredith was fed up with Gibbon’s strict rules, and he secured leave to meet with his Indiana political friends in Washington to see about replacing the general or having his regiment transferred to another brigade.

Despite the efforts of Meredith and his political cronies, the Indiana regiment was not transferred and Gibbon was not removed. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton told Meredith and his friends that the matter was in the hands of 1st Corps commander McDowell, who, despite pressure from Hoosier political forces, refused the request to move the 19th Indiana from Gibbon’s brigade.

Meredith and his soldiers soon had more serious matters on their minds. The real war finally caught up to their brigade when the regiments were ordered on a series of marches in early August 1862 to find Confederate Maj. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s forces. With McClellan stalled outside Richmond, Jackson had slipped out of the defensive lines and headed for central Virginia to cause trouble for the Union.

Near dusk on August 28, the 1,900-member Western brigade finally found the combat for which they had longed. The column was marching along the Warrenton Turnpike, not far from the old First Bull Run battlefield, when it came under artillery fire.

Gibbon ordered the 2nd Wisconsin forward to capture what he thought was just a Confederate battery positioned near the Brawner Farm. Then, out of the woods on a far ridge line, Jackson’s massed lines of infantry swept down on the lone Wisconsin regiment.

Surprised, Gibbon quickly ordered the 7th Wisconsin and 19th Indiana forward. The 2nd Wisconsin was no sooner engaged when the 19th Indiana came up on the left. Meredith brought his men in at the double-quick. “Boys,” he called as they advanced, “don’t forget that you are Hoosiers, and above all, remember the glorious flag of our country!”

Bent Iron

The Iron Brigade was devastated at Gettysburg on July 1, 1863,

Suffering more than 60% casualties.

The casualty breakdown was as follows:

| Regiment | # Of Men in Ranks | Casualties |

|---|---|---|

| 19th Indiana | 308 | 210 |

| 24th Michigan | 496 | 363 |

| 2nd Wisconsin | 302 | 233 |

| 7th Wisconsin | 364 | 175 |

| 6th Wisconsin | 344 | 168 |

| Total | 1,814 | 1,152 |

The Iron Brigade never regained the strength it had before Gettysburg. The 2nd Wisconsin and the 19th Indiana mustered out in 1864, and the 7th Indiana and a New York sharpshooter regiment were patched into the brigade at various times. The brigade was finally dissolved in February 1865. –D.B.S.

For 90 minutes, until it was too dark to see, both sides fired at each other at murderously close range during what would evolve into the three-day Second Battle of Bull Run. Gibbon, who’d see much fighting during the coming months, said later that “the most terrific musketry fire I have ever listened to rolled along those two lines of battle. It was a regular stand up fight during which neither side yielded a foot.”

As a result of his injury, Meredith missed the remainder of the battle, but was back in command when the brigade saw action at South Mountain, Md., on September 14, 1862. When his regiment stalled in the face of steep terrain and heavy opposition along the National Road, he sent his son, Samuel, to Battery B to request that two guns be brought up to bombard a Confederate strong point.

Lieutenant James Stewart was battery commander, and he later said that he looked up to see approaching “the youngest and tallest, as well as the thinnest man I ever saw.” The young officer saluted and said, “Father wants you to put a shot into that house; it is full of rebel sharpshooters.”

A native of Scotland, Stewart was a long-serving Regular and in his trademark blunt manner asked, “Who in thunder is your father?” “Colonel Sol Meredith of the 19th Indiana,” was the reply.

The veteran looked the young man up and down. “You go back with my compliments to your father, Colonel Sol Meredith, of the 19th Indiana, and tell him I will require him to give me a written order to shell that house.”

Young Meredith rode off, and returned with his father a few minutes later. “I want you to shell that house,” Long Sol told the artilleryman. When Stewart reiterated he wanted a written order, the colonel responded with “By Jinks, I will give you a written order,” and acquiesced.

Stewart rolled two guns forward and threw what Meredith called “several splendid shoots…causing a general stampede.” The Rebels gone, the 19th Indiana again pressed up the hill. “It was a most magnificent sight to see the boys of the Nineteenth going forward, crowding the enemy, cheering all the time,” the colonel would write.

Meredith suffered an injury at South Mountain, and left the regiment to go to Washington to recuperate, and also to lobby for a general’s star. While he was away, the Iron Brigade fought at the Battle of Antietam and Lt. Col. Alois Bachman was killed while leading the 19th. Not long after that battle, Gibbon was promoted to division command. The news brightened hopes for a promotion for Long Sol, a wish granted in November when he was named a brigadier general.

Now he needed a command to go with his new star and none appealed to him more than the “Iron Brigade”—as the Midwestern regiments had been christened for their hard fighting at South Mountain. Meredith was quick to approach the new Army of the Potomac commander and soon had Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s recommendation. “I have been assigned to this glorious old ‘Iron Brigade’,” he wrote to his friend and patron Governor Morton. He said he considered it “a very high compliment.”

Gibbon was outraged that Meredith had been promoted instead of his choice, Colonel Lysander Cutler of the 6th Wisconsin. Gibbon disliked Meredith’s discipline methods, and also thought he should have been present at Antietam. He approached Burnside and tried to have the appointment blocked, but the army commander turned down Gibbon’s request, saying Meredith’s “many strong friends” made such a move impossible.

The new Brigadier General and his command escaped heavy fighting at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville, but by June 1863 they were on the march to Pennsylvania and chasing Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

On the morning of July 1, Meredith was slow getting his regiments out of camp at Marsh Creek south of Gettysburg. He and his men were unaware gunfire was already being exchanged northwest of town between Federal cavalry and Confederate infantry.

Infantry musket fire was flaring north of a fenced road—the Chambersburg Pike—as the Westerners moved through the swale by the Lutheran Seminary Building. The 6th Wisconsin was halted as a reserve, while the four leading regiments advanced up the slope of a ridge to the west.

Major General John Reynolds, commanding the advance of the Union army, followed the leading 2nd Wisconsin, shouting “Forward for God’s sake, and drive those fellows out of those woods!” Brigadier General James Archer’s Brigade fired “a most murderous volley,” but the Black Hats surged forward and the surprised Confederates, expecting only cavalry or militia, retreated. Behind them, Reynolds had been shot and was dying.

At the same time, the 6th Wisconsin rushed north of the Chambersburg Pike and caught an advancing Confederate brigade in an unfinished railroad cut, capturing scores of Johnnies and the flag of the 2nd Mississippi Infantry.

By noon, the field was quiet as arriving Confederates consolidated for a final push. The 2nd and 7th Wisconsin, 24th Michigan, and 19th Indiana were posted in a thin patch of trees known as Herbst Woods at the western base of McPherson’s Ridge. It was an awkward position, as the line had to curve down to a hollow to reach the 19th Indiana.

Colonel Henry Morrow of the 24th Michigan asked three times to better position his line, but Meredith refused. Major General Abner Doubleday, now in command of the field, had ordered Long Sol to hold the woods at all costs, and that was exactly what he was planning to do.

The Confederates came in heavier numbers in the early afternoon to clear the two ridges northwest of Gettysburg and capture the town. The outnumbered Black Hats were suddenly in a desperate fight to delay the Confederate advance so the Union army could concentrate south of Gettysburg. The lines were at times merely 90 feet apart as both sides fired furiously in the smoke-filled woods.

The Confederate pressure became too much, and the Union line was flanked on both ends and began a stubborn retreat. Before the Federals backed to the crest of Seminary Ridge, however, Meredith was already down, struck on the head by a piece of shell that fractured his skull. His horse had also been killed and had fallen on him, breaking his ribs and injuring his right leg.

The wounded general was taken from the field. A few days later he would return to Indiana to recover. In November, he rejoined the army, but active field service was too much for him. After a time he was appointed garrison commander at Cairo, Ill., and later at Paducah, Ky.

There was a happy reunion with his 19th Indiana in January 1864, when the three-year veterans returned to Indianapolis for a 30-day furlough. A special reception was organized at the Masonic Hall, and when Long Sol appeared, his old boys greeted him with cheer after cheer. These men, the tall general told the crowd, shared in all the honors won by the Army of the Potomac and the welcome received “at the hands of friends at home compensates all they have endured.”

It all turned sour the next day, however, when Meredith’s son, Samuel, still troubled by his Brawner Farm wound, fell ill and died. The general buried his son and was then confined to his room with fever and exhaustion. He was still spitting up blood from his Gettysburg injuries.

Politics called him again in mid-1864, when at Governor Morton’s urging he unsuccessfully ran for the House of Representatives against incumbent George Julian. Hard words were exchanged during a bitter campaign, which included false claims that Meredith was a Southern sympathizer.

When the tall general encountered Julian at the Richmond, Ind., railroad station, he beat the congressman almost unconscious with a livestock whip. Only Meredith’s political influence and the fact he was still in the Army enabled him to have the charges dropped.

When the war ended, Meredith returned home to Indiana to resume farming. From 1867 to 1869, he served an appointment as surveyor general of the Montana Territory, and then came home to raise prize-winning livestock. He died in 1875 and is buried in Riverside Cemetery in Cambridge City, Ind.

In the final tally, Meredith was one of those curious political officers tossed up by the Civil War, a man marked by both patriotism and ambition. His feud with Gibbon was carried out with a well-honed politician’s guile using carefully crafted letters and sly whispers to the powerful forces outside the army.

His military ability was always regarded as mixed. A soldier in his regiment had hoped for Meredith’s quick promotion to general so the regiment would be rid of his careless day-to-day handling of the command. At Fredericksburg, where his brigade was at the very left of the Union line, his lines became snarled and he was temporarily removed from command. On another occasion, the general was caught out of camp without the proper pass and asked a new colonel to intercede for him with the army commander.

But the soldiers always liked Long Sol’s rustic Western style. He was remembered in the ranks for his role in keeping a private found sleeping on guard duty from a firing squad, and for his recognition that another soldier charged with “disloyal language” probably used the words in hot anger and had already proved his loyalty in battle.

In some ways, whatever his military successes and failures, or what General Gibbon, Governor Morton, and even President Lincoln said about him, would not matter. He would go down in lore as Long Sol Meredith of Indiana on his big horse, marching the storied Iron Brigade into the hard fighting at Gettysburg.

Lance J. Herdegen is the author of several books on Civil War topics, including The Iron Brigade in Civil War and Memory. His latest book is Union Soldiers in the American Civil War. Herdegen presently does historical research for The Civil War Museum of the Upper Midwest at Kenosha, Wis. He lives in Walworth County, Wis.

Help Save Solomon

Shortly after Solomon Meredith died, his son Henry Clay Meredith hired local artist Lewis Cass Lutz to design a monument to his father. John H. Mahoney of Indianapolis was hired to do the sculpting, and when he finished the statue it was displayed at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. After the exposition ended, it returned to Cambridge City, Ind., where it was first placed at the original Meredith family gravesite until 1908, when it was relocated to Riverside Cemetery. The Iron Brigade commander’s monument, currently covered with moss that is deteriorating the statue, needs restoration. Cambridge City resident Phil Harris has organized a GoFundMe campaign to restore Meredith’s statue to glory. A professional cemetery restorer will undertake the work, and if the project comes in under estimate, any excess money will be used to clean or repair other 19th Indiana Infantry headstones and markers that need work. For more information, go to The Solomon Meredith Monument Restoration Project and Restoring Solomon Meredith Monument’s GoFundMe Page.