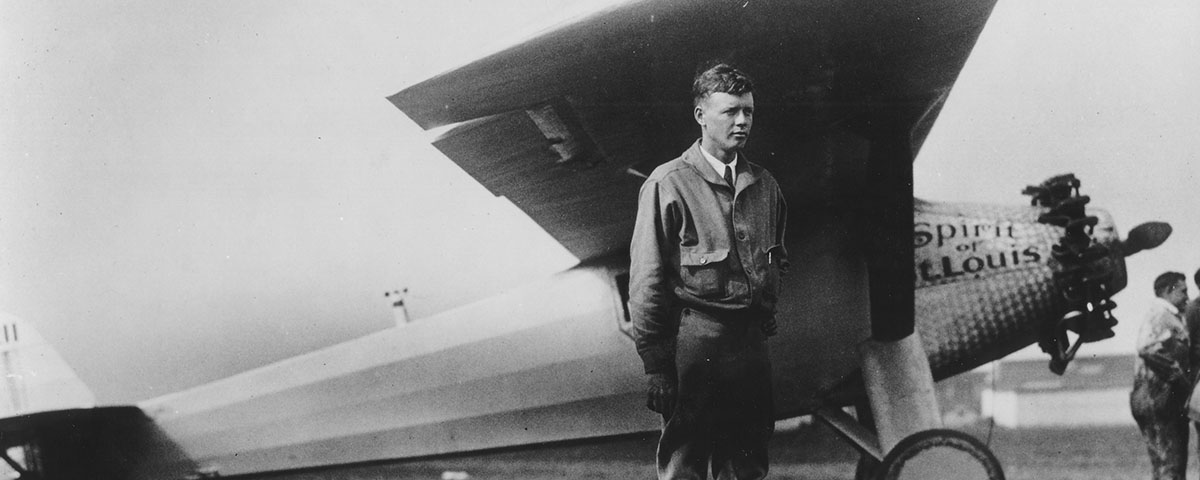

Before he gained a worldwide reputation as “Lucky Lindy,” Charles A. Lindbergh developed a solid repertoire of aviation skills.

When Charles Lindbergh set out on his solo transatlantic flight in May 1927, it signaled the beginning of one of aviation’s most exciting episodes. But the 25-year-old pilot who would be called “the prophet of a new era” had already gained a wealth of experience as a wing-walker, barnstormer and airmail pilot before he set off from New York’s Roosevelt Field to Paris on that misty May morning.

He was born on February 4, 1902, in Detroit, Mich., and his last name would have been Mansson—if his grandfather Ola had not changed his name to August Lindbergh after emigrating to America from his native Sweden in 1859. One of August’s sons was named Charles August Lindbergh. He married Evangeline Land in March 1901, and a son was born to them 11 months later. Instead of being named after his father, the baby was given a middle name that was created by adding a single syllable. And so it was the Charles Augustus Lindbergh represented the third generation of Lindberghs in America.

Young Charles’ early years were spent on a farm near Little Falls, Minn. His father was a lawyer who later represented his district as a U.S. congressman. The family moved numerous times, and Charles attended schools in a dozen different locations between Washington, D.C., and California. His travels included a trip to Panama with his mother in 1913 to see the Panama Canal under construction. Campaign trips with his father gave him the opportunity to drive an automobile and learn about its inner workings. His major interests developed along mechanical and scientific lines.

After high school, Charles entered the College of Engineering at the University of Wisconsin. But, as he later admitted, “The long hours of study at college were very trying for me. I had spent most of my life outdoors and had never before found in necessary to spend more than a part of my time in study.” His recreations were pistol and rifle shooting, as well as riding a motorcycle.

After finishing the first half of his sophomore year at Wisconsin in 1922, he motorcycled to Lincoln, Neb., and enrolled as a student at the Nebraska Aircraft Co., where he had his first flight in a Lincoln Standard. There was no ground school so he learned what he could about planes from the workers. His flying instructor was about to let him fly solo after eight hours, but the company required a student to furnish a bond to cover any damage, and Lindbergh could not afford it.

Erold G. Bahl, one of the instructors, was planning a barnstorming trip through Nebraska, and Lindbergh asked if he could go along. To help attract customers for Bahl, he began wing-walking, and he made his first jump in June 1922. For the next few months, he also wing-walked and parachuted for H.J. Lynch and barnstormed until mid-October in Kansas, Colorado, Wyoming and Montana. Lynch frequently allowed him to take the controls, and the experience made him determined to buy a plane of his own.

In April 1923 Lindbergh bought a war surplus Curtiss JN-4 “Jenny” in Americus, Ga., for $500. He received 30 minutes of dual instruction, then soloed without telling anyone. A few days later he made his first solo cross-country flight. He decided to barnstorm alone en route to Texas and sold his first passenger ride in Mississippi. He had his first accident when he nosed up in a farmer’s field near Maben, Miss., after which he replaced the prop and worked as a lone barnstormer for several months.

Lindbergh learned that the Army Air Service was accepting applications for pilot training, and decided to apply because, as he said, “I always wanted to fly modem and powerful planes.” After passing the exams, he was ordered to report to Brooks Field, at San Antonio, Texas, on March 15, 1924.

He sold his Jenny and joined Leon Klink, an automobile dealer, who had bought a Canuck (a slightly modified Canadian-built Curtiss JN-4C) and was learning to fly. The two barnstormed their way to San Antonio, Texas, via Mississippi and Florida, arriving in February. Since it was too early for Lindbergh to report for training, they decided to continue westward, but they had an accident at Maxon, Texas. By the time the Canuck was repaired, Lindbergh had to return to San Antonio, and Klink continued on to California alone. At that point, Lindbergh had logged 325 hours of pilot time.

Lindbergh was enlisted as a flying cadet and completed the rigorous year off flying and ground school training at Brooks and Kelly fields. Training at the latter included cross-country and formation flying and gunnery in World War I de Havillands, then transition flights in more advanced aircraft. During a formation flight on March 6, 1925, Lindbergh made his first emergency parachute jump after his plane collided with another student’s. Both bailed out and were back flying again within an hour.

Out of a class of 104, only Lindbergh and 17 others received their wings in the spring of 1925. They were commissioned second lieutenants in the Air Service Reserve Corps and relieved from active duty to return to civilian life. Lindbergh promptly returned to barnstorming and carnival flying in a rented OX-5 Standard in St. Louis. He instructed students and flew on several circus and passenger-carrying engagements while waiting for a permanent job with the Robertson Aircraft Co. in St. Louis, hoping to fly the mail if the company was awarded a contract by the post office.

On June 2, 1925, he was forced to make a second emergency jump while testing a new four-passenger plane for Robertson called a Plywood Special. Having put the plane in a spin to test its recovery capabilities, he could not pull it out. He finally jumped when only about 350 feet from the ground. “A strong wind was drifting me towards a row of high tension poles,” he recalled, “and it was necessary to partially collapse the chute in order to reduce the descent and land before striking the wires. I landed rather solidly in a potato patch and was dragged over a road before several men arrived and collapsed the chute.”

Meanwhile, Lindbergh joined the 110th Observation Squadron of the Missouri National Guard and was commissioned a first lieutenant. A mail contract was awarded to Robertson on April 15, 1925, and Lindbergh began flying the St. Louis-Chicago route.

“Our route was not lighted at first and the intermediate airports were small and often in poor condition,” he recalled. “Our weather reports were unreliable and we developed the policy of taking off with the mail whenever local conditions permitted. We went as far as we could and if the visibility became too bad we landed and entrained the mail.”

Flying in fog and at night resulted in many accidents for airmail pilots. Those hazardous conditions caused Lindbergh’s next two emergency parachute jumps. One was on the night of September 16, 1926, after takeoff from Peoria under clear skies. He ran into fog but managed to fly under it and headed on a compass course for Chicago’s Maywood Field. Lindbergh churned around for about two hours until his gas ran out and he had no choice; he jumped and landed in a cornfield.

Six weeks later, on November 3, Lindbergh had to make another jump while en route at night from Springfield to Peoria. He was headed for Chicago when he encountered fog over Peoria and climbed to 13,000 feet, searching for cloud breaks. When he could not find any, and his gas was gone, he bailed out and landed near Covell, Ill., on a barbed-wire fence. Fortunately, the barbs did not penetrate his flying suit. He could not find the wreck in the fog, so he got a ride to Chicago, flew another plane to the area next morning, and located the remains of his original plane only 500 feet from where he had landed the night before. At that point he was the first pilot in history to have made four successful emergency parachute jumps.

Shortly after that episode, Lindbergh began thinking about New York-to-Paris flight, motivated by the offer of French-born Raymond Orteig, who owned hotels in both cities. Orteig’s Hotel Brevoort in New York City became headquarters for French and American aviators who had visited the city during World War I. Proud to be their host, Orteig joined the Aero Club of America.

On May 22, 1919, Orteig had offered $25,000 “to the first aviator who shall cross the Atlantic in land or water aircraft (heavier-than-air) from Paris or the shores of France to New York, or from New York to Paris or the shores of France, Without stop.” The prize went unclaimed for seven years, but by 1926 several European and American pilots were planning to compete for it. The first to try flying eastbound from America was World War I French ace Rene Fonck with a crew of three in a Sikorsky S-35 trimotor, but they crashed on takeoff from Roosevelt Field, Long Island, on September 21, 1926, and two of the crew members were killed.

Next, Noel Davis and Stanton H. Wooster became the first Americans to announce publicly their intention to fly from New York to Paris. Their plane was a modified Huff-Daland Keystone trimotor bomber. Then Richard E. Byrd, fresh from his acclaimed but unsubstantiated claim that he had reached the North Pole, declared he was going to make the flight in a Fokker trimotor. Clarence Chamberlain announced he was going to fly a single-engine Bellanca in the competition.

French fliers planning to fly westbound included Charles Nungesser and one-eyed Francois Coli, who intended to fly a Levasseur-designed trimotor. Their competitors, Paul Tarascon and Dieudonne Coste, were obtaining a Breguet for their projected flight. British pilots Frank T. Courtney, F.W.M. Downer and R.A. Little planned to make their attempt in a Dornier Wal seaplane. German fliers were considering flights in Junkers-built planes.

Recommended for you

Custer was from the first 13 German immigrant families. They arrived in North America about 1693 from Krefeld and The Rhineland area in Germany. He had older-half siblings, a younger sister and unhealthy brother as well as two healthy younger brothers who served and died with him at Little Bighorn. He had a wide range of nicknames: Autie, Armstrong, Boy General, Iron Butt, Hard Ass, Ringlets.

Lorem Ipsum is simply dummy text of the printing and typesetting industry. Lorem Ipsum has been the industry’s standard dummy text ever since the 1500s, when an unknown printer took a galley of type and scrambled it to make a type specimen book. It has survived not only five centuries, but also the leap into electronic typesetting, remaining essentially unchanged. It was popularised in the 1960s with the release of Letraset sheets containing Lorem Ipsum passages, and more recently with desktop publishing software like Aldus PageMaker including versions of Lorem Ipsum.

It is a long established fact that a reader will be distracted by the readable content of a page when looking at its layout. The point of using Lorem Ipsum is that it has a more-or-less normal distribution of letters, as opposed to using ‘Content here, content here’, making it look like readable English. Many desktop publishing packages and web page editors now use Lorem Ipsum as their default model text, and a search for will uncover many web sites still in their infancy. Various versions have evolved over the years, sometimes by accident, sometimes on purpose (injected humour and the like).

The more Lindbergh thought about how aircraft had improved since World War I, the more possible the flight seemed to him. “Several facts soon became outstanding,” he later recalled in his book We. “‘The foremost was that with the modem radial air-cooled motor, high lift airfoils, and lightened construction, it would not only be possible to reach Paris but, under normal conditions, to land with a large reserve of fuel and have a high factor of safety throughout the entire trip as well.”

Lindbergh asked William B. Robertson, owner of Robertson Aircraft, and several St. Louis businessmen if they would finance such a project. They were cautiously encouraging, so he went to New York to obtain information about available planes, engines and equipment. He rationalized that a single-engine monoplane would be better than a trimotor biplane, saying: “A single motored plane, while it is more liable to forced landings than one with three motors, has much less head resistance and consequently a greater cruising range. Also there is three times the chance of motor failure with a tri-motored ship, for the failure of one motor during the first part of the flight, although it would not cause a forced landing, would at least necessitate dropping part of the fuel and returning for another start.”

He first considered buying a single-engine Bellanca, but the price was too high and delivery would take too long. He also checked on a Fokker but Tony Fokker would not consider turning out a single-engine plane for such a flight. The Travel Air Co. of Wichita, then building a cabin plane, also turned him down.

Lindbergh had learned through other pilots about an excellent monoplane used by airmail fliers built by Ryan Aeronautical Co. in San Diego. The company’s founder, T. Claude Ryan, had dissolved his partnership with B. Franklin Mahoney but remained as manager, and the firm kept his name. Lindbergh wondered whether Mahoney and Ryan would consider selling one of their planes.

It was difficult to convince the businessmen in St. Louis to bankroll his flight at first, but Lindbergh’s enthusiasm was persuasive and a fund of $15,000 was developed, including $2,000 of Lindbergh’s own savings. On February 3, 1927, a telegram, prepared by Lindbergh but signed as if coming from Robertson Aircraft Co. to get their attention, arrived at the Ryan factory in San Diego: “Can you construct Whirlwind engine plane capable flying nonstop between New York and Paris stop If so please state cost and delivery date.” Ryan called in Donald A Hall, a young engineer he had recently hired, to discuss the proposed flight. They agreed that the flight could be accomplished in a single-engine monoplane with a great overload of fuel. Ryan responded to Lindbergh: “Can build plane similar M one but larger wings capable of making flight cost about six thousand without motor and instruments delivery about three months.”

An answer quickly followed, asking whether the plane could be built in less than three months because of the competition that was rapidly developing. Ryan replied that they could furnish a plane in two months and would require a 50 percent deposit. Lindbergh immediately went to San Diego and liked what he saw. He recommended the backers accept the deal, and an order was placed on February 28, 1927, for a plane equipped with a Wright Whirlwind engine, costing $4,000.

Lindbergh and Hall worked closely on construction details of a plane resembling the M-2. Hall was surprised that Lindbergh was going to fly alone, but it made the designing easier. There would be no radios or night-flying equipment. To provide a structure capable of handling the weight of the extra fuel on takeoff an extended wing and wide-wheel-tread landing gear were designed. Lindbergh wanted the cockpit placed in the aft position behind the main fuselage tank, not between the engine and the tank, where he could be crushed in an accident. That restricted forward visibility, but Lindbergh did not see any disadvantage, noting that “I will be flying by instruments and there will probably be no one I will run into out over the Atlantic Ocean.”

Workers at the plant, caught up in Lindbergh’s quiet enthusiasm, labored day and night on their new assignment. At one point during the assembly, a shy workman named A.C. Randolph, a former submariner, was concerned about the pilot’s restricted visibility. He approached Lindbergh with drawings for a simple periscope. Lindbergh approved the idea, and one was installed, although he preferred to poke his head out the window.

The name of the plane, Spirit of St. Louis, had been agreed upon by the eight businessmen who had contributed to the fund. Lindbergh stayed at the plant as construction continued seven days a week. Some workers voluntarily put in double shifts. Hall, on one occasion, worked 36 hours without resting.

Lindbergh had never made an overwater flight before or flown more than 500 miles nonstop. He gathered Rand McNally state maps for the flight to New York, but since he would be flying a great circle route over the ocean without landmarks, he spent hours plotting the track he would follow on a variety of charts.

“From New York to Paris; he said, “I worked out a great circle, changing course every hundred miles or approximately every hour. I had decided to replace the weight of a navigator with extra fuel, and this gave me about three hundred miles additional range. Although the total distance was 3,610 miles, the water gap between Newfoundland and Ireland was only about 1,850 miles, and under normal conditions I could have arrived on the coast of Europe over three hundred miles off my course and still have enough fuel remaining to reach Paris or I might have struck the coastline as far north as Northern Scandinavia, or as far south as Southern Spain and landed without danger to myself or the plane, even though I had not reached my destination. With these facts in view, I believed the additional reserve of fuel to be more important on this flight than the accuracy of celestial navigation.”

As the plane was taking shape, Lindbergh accumulated and carefully weighed the equipment he would carry, including a raft in case he had to ditch. In addition to food to eat during the flight, he included five cans of concentrated Army rations and a gallon of water, plus an Armburst cup, a device for condensing the moisture from human breath into drinking water. There would be no parachute. Meanwhile, the newspapers carried stories about others on their New York-to-Paris projects. Chamberlain had set an endurance record of more than 51 hours on April 14; Byrd’s plane had an accident on the 18th; and Nungesser stated that he would leave France on April 24. Two days later, Noel Davis and Stanton Wooster were killed on takeoff from Langley Field, Va. That left Byrd, whose plane was repaired, and Chamberlain still in the running, although Chamberlain had a takeoff accident on April 24.

On April 28, 1927, just over two months after the order had been placed, Lindbergh was ready to give the Spirit its first test flight. “Today, reality will check the claims of formula and theory on a scale which hope can’t stretch a single hair,” he said. “Today, the reputation of the company, of the designing engineer, of the mechanics, in fact every man who had hand in building the Spirit of St. Louis, is at stake. And I’m on trial too, for quick action on my part may counteract an error by someone else, or a faulty move may bring a washout crash.”

He was immediately pleased with the Spirit‘s performance. “The plane was off the ground in six and one-eighth seconds, or in 165 feet,” he said, “and was carrying over 400 lbs. in extra gas tanks and equipment.” He noted its top speed was 130 miles per hour and that it was very stable in banks and stalls.

Lindbergh’s greatest concern was weight. He made progressively heavier load tests away from prying newsmen at an abandoned Army post, and speed runs were flown on a three-kilometer course along Coronado Strand. When he was satisfied with its capabilities, he took the plane to nearby Rockwell Field and made more load tests with up to 300 gallons of fuel.

On May 8, Nungesser and Coli left Paris, the first plane to take to the air en route to the other side 0f the Atlantic in the competition. Newspapers reported their expected progress, but they vanished and were never found. Now only Chamberlain in his Bellanca was left. as the most promising competitor, although Byrd was still hedging about his intended takeoff date and declared that he was not concerned about the prize.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Lindbergh left from Rockwell Field on the afternoon of May 10 for St. Louis, escorted briefly by two Army Air Corps observation planes and a Ryan monoplane. He flew a compass course and headed over Arizona’s wildest mountains as haze and darkness obscured checkpoints below. A lazy moon gave him some light, and all instruments were reportedly operating normally.

Suddenly, the engine began to sputter and shake, a familiar danger sign. He was over mountains and could not identify any possible landing spaces in the darkness. He tried various throttle and mixture control settings, and in spite of the ominous coughing and sputtering, the Whirlwind engine was still putting out some power. He asked himself, “Will some miracle keep my Whirlwind going while I circle between these mountain ridges through the night?…Each minute makes my fuel load a little lighter, reduces my landing speed some fraction of a mile. Each minute separates me that much farther from the earthly impact that’s almost certain to be crushing to my body and my plane.” He considered returning to San Diego, which was five hours behind him, but that would mean flying over high mountains again, so he continued eastward as the engine continued its uncertain rhythm. He thought briefly he might turn south toward Mexico, where the mountains were lower. “I have plenty of fuel in the tanks,” he wrote in The Spirit of St. Louis (1953), “but that would destroy the check on navigation which is the main object of the flight. It’s extremely important to see how far off route I am when the sun rises. If serious errors have crept [in,] I must learn about them before I start across the ocean.”

He was able to ease up to 13,000 feet over the Continental Divide, and when he had cleared the summits, he descended into warmer air and the engine ran more smoothly. He knew then the problem was carburetor icing. “I’ll have a carburetor heater put on in New York,” he told himself. “The warning I received tonight may save my life over the North Atlantic, flying in still colder air.” This incident was not revealed in We, his first book, published in 1927. No one knew for a long time how close he might have come to never realizing his dream.

Reaching St. Louis in early morning, he circled the business district as he had promised his backers, then landed at Lambert Field 14 hours, 25 minutes after takeoff. Next morning, he departed Lambert and arrived at Curtiss Field, Long Island, 7 hours and 20 minutes later. The total flying time of 21hours, 45 minutes was an unofficial record for a coast-to-coast flight. Lindbergh was immediately besieged by photographers, newsreel cameramen and reporters. The question most often asked was when he would leave for Paris. His standard answer was, “I’ll go when everything is right,” referring to the installation of a new compass, a thorough engine check and satisfactory weather.

The next few days were spent working with engine and instrument experts, and checking nearby Roosevelt Field, which seemed safer than Curtiss Field for the takeoff. When the plane was ready, it remained for Weather Bureau meteorologist James H. Kimball to indicate the best time to depart. On Thursday, May 19, the forecast was encouraging. The Spirit was moved to Roosevelt Field and the fuel tanks topped off. A barograph was installed by a representative of the National Aeronautic Association to ensure that the flight would be officially sanctioned.

It was misty and raining lightly on Friday morning when “Lindy,” as the press had dubbed him, climbed into the wicker seat. “Sitting in the cockpit, in seconds, minutes long,” he recalled, “the conviction surges through me that the wheels will leave the ground, that the wings will rise above the wires, that it is time to start the flight.” It was 7:54 a.m., May 20, 1927, as he slowly began the takeoff. The plane felt like “an overloaded truck” at first, without “the magic quality of flight.” But gradually the controls stiffened as the halfway point passed. It bounced twice, as if to protest leaving the ground, but finally rose in triumph and cleared by 20 feet the telephone wires at the end of the field. The Spirit was quickly lost in the mist as it made its way into history.

We know about the successful outcome of this flight and the unprecedented reception Lindbergh received. His flight had taken on a significance far beyond his imagination. “I had entered a new environment of life,” he said, “and found myself surrounded by unforeseen opportunities, responsibilities, and problems.”

But everlasting fame was not to be denied. Louis Bleriot, first to cross the English Channel by air, summed up the achievement most succinctly when he kissed an embarrassed Lindbergh on both cheeks and said, “You are the prophet of a new era.”

The late C.V. Glines was an award-winning author and a member of Aviation History’s Editorial Advisory Board. For additional reading: We, by Charles A. Lindbergh; The Spirit of St. Louis, by Charles A. Lindbergh; and Lindbergh, by A. Scott Berg.

Originally published in the May 2002 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.