On a hot day in September 1806, with flags flying, Lieutenant Facundo Melgares led some 300 Spanish army troopers and New Mexico militiamen into a large Pawnee camp on the Platte River in what is now Nebraska. Melgares, whose force had set out three months before from the provincial capital, Santa Fe, had orders to intercept and arrest certain Americans known to be traveling unlawfully in Spanish territory and said by an American informer to be descending the Missouri River. The American trespassers’ names were William Clark and Meriwether Lewis.

Melgares had departed Santa Fe on June 15 with 105 Spanish regulars, 400 New Mexican militiamen, and 100 American Indians. At the Arkansas River near present-day Larned, Kansas, Melgares left 240 men with instructions to build a fort; he led the rest of his contingent north on the king’s business. He had to tread lightly. His orders were to keep the peace with the Pawnee at all costs.

Unbeknownst to Melgares, at that moment Lewis and Clark were 140 miles east, sailing down the Missouri River toward the frontier town of St. Louis. At his village, Pawnee Chief White Wolf refused to let the Spanish continue, seemingly ready, Melgares thought, to fight if pressed. Melgares could only persuade the Pawnee to fly Spain’s flag exclusively and keep Americans off their lands. He arrested two French trappers found in the village for trespassing. Around September 11, captives in tow, he made for Santa Fe. Unaware they were targets, Lewis and Clark proceeded to St. Louis, there ending a 29-month round-trip odyssey to the Pacific.

Melgares and his men made up the last of four Spanish forces sent to arrest Lewis and Clark. Each contingent just missed its assigned troop of Americans, whether it was traveling up the Missouri or bound back to St. Louis. The Spanish considered these ventures evidence of espionage and meant to stop all four.

The American troops were following President Thomas Jefferson’s orders to map the acreage acquired when the United States bought the Louisiana Territory in 1803 from France. Spain, however, viewed that deal as illegal because in 1863, at the end of the Seven Year’s War between France and Britain, France had signed the land over to the Spanish crown to ensure that Britain didn’t grab the prize.

The Spanish pursuit of Jefferson’s expeditions is a chapter in the emergence of the young United States as a continental nation, pushing at its borders and testing Spain’s claim on the Louisiana Territory, itself a vestige of the sprawling Seven Years’ War.

Lands west of Appalachia were filling with enterprising settlers open to gain wherever it might arise. Jefferson’s drive collided with the perfidy of two of his peers—one an effective army commander later called a “mammoth of iniquity” during a trial for corruption; another a political rival with his own land-grabbing ambition—and courted war with Spain.

In its efforts to thwart the Americans, Spain had a mole in the Jefferson administration who was on its side. Secretly working for the Spanish, General James Wilkinson leaked details on each westward lunge. Wilkinson was addicted to scheming. As a Revolutionary War officer, he had joined in the plot to remove Commander-in-Chief George Washington. As second in command of the Legion of the United States for the reinvasion of the Old Northwest, Wilkinson maligned his boss, legion commander Anthony Wayne, hoping to replace Wayne. In 1787 Wilkinson offered Spain his services as a spy helping to get the western states to secede. He began reporting to Spanish handlers in New Orleans in 1794 but hadn’t had much involvement in the leadup to Jefferson’s westward expedition. When Jefferson took office as president in 1801, Wilkinson was senior Brigadier General. Soon after buying Louisiana, Jefferson placed frontier forces under Wilkinson’s command. Wilkinson hastened to get back on Spain’s payroll, demanding pay for his inactive years and a retainer for services to be rendered. Fearful of Americans flooding their provinces, Spain settled 12,000 gold pesos on Wilkinson as back pay and agreed to a $4,000 annual stipend.

In gaining nominal title to Louisiana, Jefferson had acquired the land adjoining New Orleans and St. Louis—plus the preemptive right to obtain Native American lands in Louisiana by treaty or force to the exclusion of other colonial powers. Spain administered the west bank of the Mississippi south from St. Louis but had no problem with the Americans assuming control of that side of the river, which seemed inevitable. Since 1799 Daniel Boone and Henry Dodge had been leading American settlers to St. Louis, becoming such presences that Spanish authorities made Boone and other Americans judges there. Spain did object to American claims on lands further west. Spain had bled for these expanses, a gateway to gold and silver deposits in what is now Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and California. The United States had practical reasons for buying Louisiana: the port of New Orleans, and control of the Mississippi. But American revolutionaries like Washington and Jefferson envisioned the new nation stretching to the Pacific. Louisiana offered an overland route to the western ocean.

The first American attempt at traversing the continent came the year that America won independence. Learning in 1783 of British intent to send a party across the continent, Jefferson asked General George Rogers Clark about trying to beat the British west with a large force. Clark argued that a martial display would anger Native tribes. Send three to four men, he said. In 1790, Secretary of War Henry Knox sent Lieutenant John Armstrong to see what was beyond the Mississippi; underfunded, he stopped at the big river. In 1793, the American Philosophical Society took a run at the Pacific, funded partly by President George Washington, financier Robert Morris, and Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton. Jefferson named French botanist André Michaux its leader. To avoid nettling the Spanish, the government told Michaux to cross the Mississippi north of St. Louis. He and his men set out in June, but when Michaux was revealed to be a French agent assigned to attack Spanish positions along the Mississippi, Jefferson scrapped the project and sent Michaux back to France. American dreams of the Pacific lapsed until Alexander Mackenzie, a Scot working for the North West Company of Canada, reignited that ardor in 1793. Mackenzie became the first European to cross the continent north of Mexico and reach the Pacific, painting his name in red on a rock along the Canadian coast.

In 1802, thanks to social connections, outdoorsman and former soldier Meriwether Lewis was President Jefferson’s secretary when his boss obtained a copy of Voyages from Montreal, Mackenzie’s account of his feat. In the 1801 volume, the explorer urged Britain to develop a land passage across North America. That incitement and the image of a rock daubed in red transfixed Jefferson. He said he would soon be sending Lewis on just such a quest. Jefferson sounded out Spain’s ambassador on whether a Pacific-bound expedition crossing Spanish holdings would sit well with the king. Ambassador Carlos Martinez de Yrugo said Spain would view such efforts as a hostile act, even if the ostensible point was only to map unknown territory.

The mysterious expanse fired Jefferson’s curiosity. Lewis’s instructions from Jefferson for the journey included looking for Welsh descendants from Prince Madoc’s 1170 expedition to the New World, hunting for mammoths, and collecting evidence that Native Americans were human beings. Jefferson did know that the Rocky Mountains were the source of most of the rivers feeding the Mississippi from the west. Working with Captain Robert Gray’s 1792 discovery and precise mapping by longitude and latitude of the mouth of the Columbia River along North America’s Pacific Coast, Jefferson acquired a rough idea of the distance between the east coast and the west coast as a crow flew. Spanish fur traders had been trapping and bargaining for skins on the upper reaches of the Missouri River for decades. In 1795 Spanish merchants in St. Louis sent an expedition up the Missouri seeking a route to the Pacific. Two years later the exploratory party returned with detailed maps of the Missouri. By 1802, Spain had installed 11 trading posts on the Upper Missouri.

When French officials offered American negotiators all of Louisiana in 1803, Jefferson grabbed it. The deal dovetailed perfectly with his aspirations for an overland route to the Pacific Ocean. Jefferson ignored a festering decades-old border dispute over whether the Sabine River marked the border between French and Spanish holdings. The French said it did, while the Spanish claimed the border was further east within the Mississippi drainage.

Jefferson hurriedly assigned four expeditions to explore particular aspects of Louisiana. Lewis, with George Rogers Clark’s younger brother William and a few men, would go up the Missouri and head west for the Pacific.

A second party would explore the length of the Red River, previously the northern boundary separating the Spanish province of Texas from Louisiana and now the new southern border separating the United States and New Spain. Jefferson wanted to know if the Red River ran west to Santa Fe in New Mexico. The third expedition would travel up the Kansas River and onto the Great Plains, hunting the Red River’s source. A fourth expedition would travel up the Arkansas River mapping that waterway.

Learning of Jefferson’s expeditionary plans, Wilkinson, Spanish secret agent and commander of American forces on the frontier, alerted his Spanish handlers. Ever the conspirator, Wilkinson also had signed onto former Vice President Aaron Burr’s scheme to grab part of lower Louisiana, merge it with a few northern provinces of New Spain, and form a new nation.

Jefferson explicitly ordered Lewis to avoid Spanish settlements. When intelligence suggested the Arkansas River expedition, set for 1804, would encounter Spanish troops, Jefferson canceled it. By this time Lewis and Clark were two months into their trip up the Missouri. That was when Wilkinson squealed to the Spanish, suggesting they intercept the men of the Corps of Discovery and repel or arrest them.

Nemesio Salcedo, commandant general of the Internal Provinces of New Spain, headquartered in Chihuahua, worried that “Captain Merry” intended to “penetrate the Missouri River in order to fulfill the commission which he has of making discoveries and observations.” Salcedo feared “Merry’s” discoveries would include pinpointing Spain’s gold and silver mines in the mountainous West. Salcedo sent Pedro Vial north after the American explorers three times. Vial was too early to the Pawnee village and had been gone a month when, slowed by a slow spring melt on the frozen Missouri, Lewis and Clark reached the mouth of the Platte on July 21. Vial left Santa Fe on his second foray on October 5, 1805, with 100 men, but they clashed with Native warriors while crossing the Arkansas River in today’s eastern Colorado and turned back. In his third attempt, Vial left in April 1806, again turning back owing to desertions in the ranks. Now Salcedo sent Melgares, who chose to maintain peace with the Pawnee rather than chase Lewis and Clark.

Five months after Lewis and Clark left St. Louis for the west, Jefferson approved a smaller expedition up the Ouachita River by way of the Red River. That undertaking was headed by Dr. William Dunbar, a friend of Jefferson’s who had been set to lead the aborted Arkansas expedition. Dunbar, keen to find a medicinal hot spring said to be in the unexplored region, pitched his idea to Jefferson rather than going through Wilkinson. Jefferson approved the plan through a personal letter to Dunbar with the promise of funding, again leaving Wilkinson out of the loop.

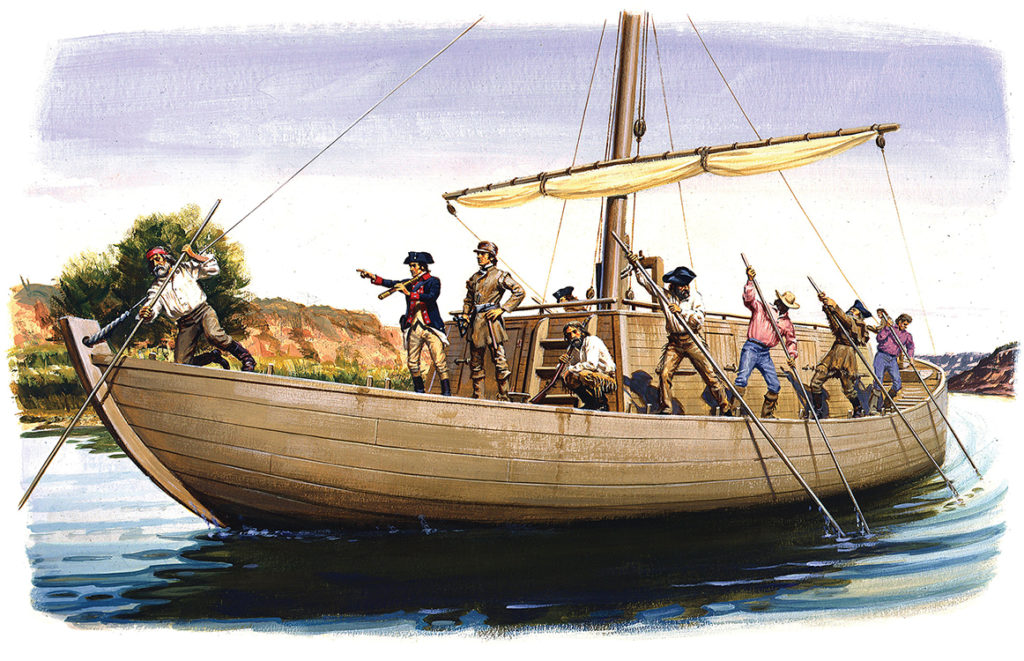

Along with chemist George Hunter, the Dunbar party consisted of 13 soldiers, Hunter’s teenage son, Dunbar’s two slaves, and Dunbar’s servant. The expedition left St. Catherine’s Landing on the east shore of the Mississippi on October 16, 1804. The men were aboard a boat designed by Hunter and built in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, months earlier. The team quickly realized the craft, a “Chinese-style vessel,” drew too much water for the shallow rivers they were traveling, but they bumped upstream on the Red River, onto the Black River, and finally the Ouachita, which brought them to the storied medicinal waters—today’s Hot Springs, Arkansas. Hunter made studies on water quality while Dunbar calculated the rate of discharge of the springs. The degree to which the supposedly empty area had been settled amazed Dunbar. Cabins harboring American, French, Spanish, and Native trappers surrounded the springs.

On their return traversing the New Orleans Territory to Fort Miro (now Monroe, Louisiana), Dunbar himself hurried overland to Washington, DC, bringing along with him flora and fauna samples and maps that he delivered to his pal, the president, the first substantial information from one of Jefferson’s expeditions. The remainder of the expedition returned by boat in January 1805. The Spanish had not interfered.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

Jefferson now wanted the seasoned Dunbar to lead the Red River expedition. He told Dunbar to obtain passports from Spanish officials since the expedition would be traveling near Spanish Texas. In New Orleans, the Marquis de Casa Calvo, former Spanish governor of Louisiana, issued passports but told the Americans he could not override Spanish authorities in Texas if the Tejanos chose not to honor the passports. Dunbar decided not to go. Command went to Thomas Freeman, who had helped survey the line between the United States and Spanish Florida. Peter Custis, a trained naturalist with a medical background, signed on as second in command. When intelligence reports warned of possible encounters with Spanish troops, U.S. Army Captain Richard Sparks, two junior officers, and 17 enlisted men were assigned to the venture. The Freeman party left Natchez, Mississippi, on April 19, 1806, traveling up the Red River in two barges and a native canoe. Because a border dispute with Spain along Louisiana’s Sabine River was heating up, the expedition took on more soldiers until Spark had 45 men.

Owing to snags and logjams, the expedition needed a month to reach Natchitoches, Louisiana, and two months more to clear the Red River Raft, a massive natural logjam, and the Great Bend of the Red River. The crawl up the Red gave Wilkinson and Calvo time to alert Spanish territorial officials of the expedition, just as Jefferson was praising the project to Congress. To stop Freeman and company, Spain sent Captain Francisco Viana, newly appointed commander of the Nacogdoches garrison in east Texas. Viana and his men rode hard north. On July 28, some 615 miles upriver, the American explorers began hearing Spanish guns. Freeman asked to parley. Viana said he had orders to fire upon any foreign troops in Spanish territory. Freeman demanded Spanish objections be put in writing and the name of the official who had sent Viana to stop him. Viana refused. Three days passed. Freeman gave in, claiming he wanted to avoid an international incident. The Red River Expedition headed downriver, embarrassing Jefferson and tickling Burr and followers.

As a result of the Sabine River dispute with Spain, war clouds gathered. Wilkinson began assembling an expedition to find the Red River’s source. Lieutenant Zebulon Pike, 27, had returned to St. Louis on April 30, 1806, from a separate quest, having spent nine months searching for the source of the Mississippi River and informing British traders in what would become Minnesota that they were trespassing. Pike had identified the wrong lake as the mighty river’s source, but no one would know that for decades. The President praised young Pike in his December 1806 message to Congress.

On his own, Wilkinson promoted Pike to captain and assigned him a new challenge. Starting in mid-July, Pike was to cut across the Great Plains to the Rockies to find the Red River’s source.

It occurred to Pike that Melgares knew where he was going, and Pike did not. Pike decided to follow him.

Locals in St. Louis, where it was held that the Red rose on the plains, scoffed, noting that Pike’s schedule would put him in the Rockies during winter. Jefferson told Pike to avoid New Mexico, but Wilkinson had ordered him to get as close to the Spanish settlements as he could with Dr. Robinson, a confidant of Aaron Burr. Wilkinson made his son James Biddle Wilkinson second in command. The 23-man Pike expedition left on July 15 with 59 Osage hostages Pike was to drop off at the nearest Osage village in what is now Kansas.

Wilkinson did not see Pike off; the Sabine River crisis had pulled him to New Orleans. But earlier the general had written Pike that if caught by the Spanish near Santa Fe he should claim to have gotten lost. Within weeks of Pike’s casting off, Governor Salcedo in Chihuahua City learned from his agents in St. Louis and from Wilkinson of the Pike expedition’s departure.

Pike reached an Osage village in eastern Kansas a month later, delivering the hostages as a goodwill gesture from the U.S. government. He then marched for the Pawnee village on the Platte River in central Nebraska. He and his force arrived September 29, missing the hapless Melgares and his troops by several weeks. Seeing the Spanish flag over Chief White Wolf’s teepee, Pike asked for a tribal council. Pike told the Pawnee they were now under the protection of the United States and were to lower the Spanish flag.

When White Wolf learned that Pike planned to proceed west, he forbade the American to take that direction, just has he had forbidden Melgares to go east. Pike was not worried about keeping the peace with the Pawnee. If anything, he was spoiling to project American power.

Pike told the chief his men were well armed and that if anything befell them, the United States would avenge their deaths. He then marched west for the Arkansas River, in two days finding a campsite the Melgares force had left. Pike counted 59 fires. The thought occurred to Pike that Melgares knew where he was going, while Pike did not. The American explorer decided to follow the Spanish soldiers’ trail.

As Pike and his men were following Melgares’s trail, Wilkinson’s troops were clashing with Spanish troops along the Sabine River. Without Jefferson’s permission, Wilkinson had signed an understanding with his Spanish counterpart, Lt. Colonel Simon de Herrera, for the withdrawal of U.S. and Spanish forces from the Sabine River to avoid war. But Jefferson accepted the understanding because it created neutral ground between the U.S. and Spain. From 1806 to 1821, the neutral strip along the Sabine was a de facto demilitarized zone that besides helping to avoid direct confrontations between Spain and the U.S. over the Jefferson-appointed incursions was a haven for outlaws and smugglers. Its creation also marked a change of direction for Wilkinson. He decided Aaron Burr and his grandiose plans for a new nation were a dangerous liability, but Wilkinson was not yet through scheming.

Two weeks of hard riding brought the Pike expedition to the banks of the Arkansas River. Near present-day Coolidge, Kansas, by the Colorado border, Pike split his force. Young Wilkinson would follow the Arkansas River downriver to civilization with five men while Pike’s group and Robinson would continue upriver.

On December 3, near present-day Pueblo, Colorado, Pike noted that Melgares’s trail suddenly had turned south, apparently taking him to Santa Fe. Instead of following, Pike continued up the Arkansas, roaming the Rockies through snow for a month before crossing the Sangre de Cristo Mountains into the San Luis Valley in what is now Colorado. Locating the upper reaches of the Rio Grande, Pike built a small fort on January 31, 1807, on the west bank of the Rio Grande, in territory undisputedly Spanish.

From there, Dr. Robinson proceeded south alone for Santa Fe. Spanish troops arrested him two weeks later as they rode north to confront Pike. Aaron Burr was arrested at approximately the same time in Alabama on charges of treason. Wilkinson had turned him in.

The night of February 26, Spanish troops stormed Pike’s Fort, arresting him and his men for spying. In Santa Fe, officials confiscated Pike’s notes and maps. After being questioned, the Americans were given travel money and allowed to keep their unloaded weapons.

Melgares and troops escorted them to Los Coabos, the capital of Chihuahua. After interrogating Pike and his men, Governor Salcedo had an armed escort take them to the Louisiana border.

As Spanish troops were taking Pike to the border, an American named Burling was making his way overland from Louisiana to Mexico City, telling Spanish authorities he had come to buy mules. He also carried a letter from Wilkinson to the Viceroy of New Spain. In the letter Wilkinson demanded $100,000 in cash. After all, he had prevented an invasion of Mexico by Burr and saved Spain from a costly war with the United States. The Viceroy gave Burling neither the money nor the mules.

Pike reached the United States on July 1, 1807. In 1813, during the War of 1812, he died at York, Upper Canada, when retreating British troops blew up an ammunition magazine. Meriwether Lewis had died of gunshot wounds in 1809, either by his own hand or murdered.

William Clark went on to serve as territorial governor of Missouri until 1822, when President James Monroe named him Superintendent of Indian Affairs, a post he held until his death in 1838. Jefferson’s protégé William Dunbar pioneered ways to make use of cottonseed oil and other improvements to plantation economies before dying on his plantation in 1810. Thomas Freeman, who had taken over Dunbar’s expedition, died in 1821 after forsaking his career as explorer and surveyor to become an astronomer.

General James Wilkinson was ordered court-martialed by President James Madison for his role in the Burr conspiracy; a military tribunal acquitted him. He was later appointed as the U.S. Envoy to Mexico in 1821. Wilkinson died in Mexico City in 1826, possibly from an overdose of laudanum. He was 68. Suspicion persisted that he was spying for Spain, but not until 1854 did correspondence discovered in that nation’s archives confirm Wilkinson’s skullduggery.

This article appeared in the Winter 2023 issue of American History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.