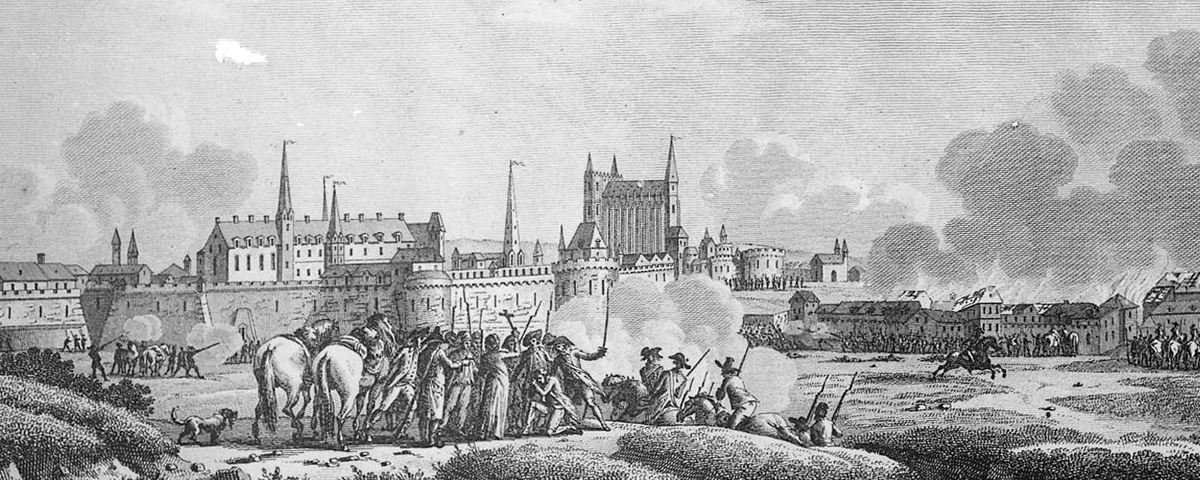

EARLY ON THE MORNING of March 11, 1793, the citizens of the small market town of Machecoul in west-central France woke to discover some 3,000 peasants moving toward them across the town’s surrounding fields. The peasants were armed with pikes, sickles, pitchforks, axes, a few ancient harquebuses, knives, hunting guns, and whatever else might serve as a weapon. Machecoul had no more than a couple of hundred national guard soldiers to defend it against the mob, and after almost four years of revolution, they were hardly the cream of the army. M The French nation was under siege from all quarters. The Jacobin revolutionaries had beheaded Louis XVI two months before, horrifying the rest of Europe, and their army had fought off the Prussians in the Battle of Valmy the previous September. Now the French army was advancing into the Austrian Netherlands. With conflict on all sides, few local guardsmen were left in the interior of the country to maintain order or to enforce the conscription of an additional 300,000 men to fight the Austrians—a conscription just getting underway in Machecoul and the region along the Atlantic known as the Vendée. Those few remaining guardsmen were either old or very young, not fit for battling the professional armies at the borders of France. On that morning in March, when they were faced with thousands of angry, shouting peasants, most of them fled.

A national guard officer named Maupassant, who had come to town to conduct the conscription lottery, confronted the crowd and tried to reason with them. A thrust of a pike to the heart killed him instantly. Then a priest was pulled from the Catholic church and stabbed repeatedly in the face with a bayonet until he was dead. The houses of anyone who served in an administrative capacity or acted for the revolutionary government in Paris were broken into; those found inside were dragged out and beaten. On the street, more than 40 men were killed. Prisoners in the local jail, imprisoned by the peasants, were taken to the fields, forced to dig their own graves, and murdered. By the time it was over, several hundred citizens of Machecoul were dead, and civil war had erupted in France.

TO THE PEASANTS, THE ANGER WAS JUSTIFIED. The French Revolution did not exactly have unanimous support. After it exploded in Paris in 1789, it spread slowly to the provinces, but it always faced opposition. In Paris, as faction replaced faction, the tone and actions of the government became steadily more radical, and in some places in France, resistance, in the form of riots, became more violent; Paris itself was often consumed in strife. By 1793 the Vendée, traditional and conservative and, like many rural areas, resistant to change, had had enough.

More or less spontaneously, peasants rose against the central government and its representatives all over the Vendée. In the northern part of the region, above the extensive marshlands fronting the Atlantic, the small town of Saint-Florent fell to the same kind of mob on the same day as Machecoul. Insurgents seized the town’s cannons from the overwhelmed national guard, then marched to nearby Chemillé and did the same thing.

More or less spontaneously, peasants rose against the central government and its representatives all over the Vendée. In the northern part of the region, above the extensive marshlands fronting the Atlantic, the small town of Saint-Florent fell to the same kind of mob on the same day as Machecoul. Insurgents seized the town’s cannons from the overwhelmed national guard, then marched to nearby Chemillé and did the same thing.

By March 14 the mob had reached the outskirts of Cholet, the most important town in the area. As they approached, a barefoot man wearing rags and carrying a large cross entered Cholet and walked the streets, advising its population to surrender and avoid bloodshed. Instead, the commander of the national guard contingent decided to resist. By then the mob had swelled to 15,000 or 20,000; it had three cannons and a man named Six-Sous who knew how to fire them. On his second shot, he killed the commander. The national guard panicked. The town was won. The mob tore into the public buildings, burned papers, and drove out the national guard. Fifteen to twenty thousand men, angry, determined, fearless, was more than a local mob. It was a force to be reckoned with.

The year 1793 was not a good time to be French. The nation was in a state of near chaos, with unrest growing internally, and murderous and deeply paranoid Jacobin fanatics in control of the government in Paris. This was the year the Terror began, the year that citizens suspected of moderation were guillotined by the thousands. It soon became obvious even to ardent supporters of the revolution that one tyranny had been exchanged for another.

Though the government bureaucracy had mostly continued to function throughout the earlier years of revolutionary chaos, in that spring a rebellion in Lyon had thrown out the representatives of the central government, and there were similar rebellions in Marseilles and a few other cities. But the revolt in the Vendée was different. It was all-out civil war, and it engaged the entire region.

Rural, isolated, politically indifferent, and deeply Catholic, the Vendée had hardly been touched by the revolution up to that point. Occupying the region south of the Loire and facing the Atlantic, the Vendée was an area of less than 1,000 square miles and a population of about 800,000, with towns and villages but no large cities. Most people lived on farms, and the farms were relatively prosperous. The northern Vendée was heavily forested, a land of steep gullies, rolling hills, and very few roads; in the south lay marshland.

Socially, the area was not divided in the same ways as the rest of France, where the nobility had long maintained homes in Paris and spent much of the year there. In the Vendée the local nobility were truly local. They lived on their estates and identified with the area and its people, who regarded them for the most part with respect and affection. As the revolution progressed, some nobles emigrated but most did not. When they could, the peasants chose the remaining nobles as military leaders in their counterrevolution against the new republican government. Anticipating what would happen in the end, when they inevitably lost, the nobles tried to talk the peasants out of revolting against the republic, but they accepted their leadership roles nonetheless. Among the noblemen leaders were the Prince de Talmont and the very young Comte de la Rochejacquelein, along with his father-in-law, Marquis de Lescure. In the marshes of the southern Vendée, the chevalier Charette de la Contrie led. A headstrong womanizer from an old, impoverished Breton family, he was a royalist and a devout Catholic.

Devout Catholicism was part of what drove the counterrevolutionaries. One of the first things the revolution had done was disestablish the Roman Catholic Church, nationalizing church property, abolishing monasteries, and forcing priests to swear allegiance to the republican government. Priests who refused were called non-jurors, ejected from their parishes, and forced to emigrate or otherwise punished for their loyalty to the church. In the Vendée priests had always been locally born and bred. They knew their people and were of them. They were trusted. The priest in Machecoul who was killed, however, was not local—he had been forced on the parish by the revolutionary government in Paris.

The Vendeans’ deep attachment to religion was matched by their love of home. In the Middle Ages most Vendeans never traveled more than 15 miles from their place of birth, and that remained generally true at the time of the revolution. Paris was remote and few of them had ever seen it; even fewer had seen the king. They considered themselves first and foremost Vendeans, not French, and had developed little or no loyalty to an abstraction called “the nation.” Though the rebels adopted the white cockade of the royalists and their war cry ran “Vive le roi; vive la reine et la religion,” it was not the royalist cause but religion and home that truly mattered to them. As for the “nation,” they were not inclined to fight its wars far from home. Quite the contrary: If they had to fight, it would be against the new nation, not for it.

FIGHT THEY DID, savagely and well. The Vendean counterrevolutionaries swept the region, overwhelming the garrisons of national guardsmen in one small town after another, taking cannons and whatever other weapons they could find. It took weeks for Paris to realize the seriousness of the situation, and when officials there finally sent “Blues” (as the republican government’s troops were called) to the Vendée, they were at a serious disadvantage: There were not enough of them to overcome the Vendeans, and they didn’t know the terrain. In the north the few roads were surrounded by forests and wound through gullies and ravines. To exacerbate the situation, the Vendeans fought like Native Americans, ambushing government columns from the forests and then moving through familiar woods to ambush again. In the fields they fought from behind hedgerows and struck with barrages of simultaneous fire that took the Blues completely by surprise. It was guerrilla warfare before there was a name for it.

This was a distinct shock to the regular French troops who opposed them. Eighteenth-century professional armies were accustomed to fighting in the open, facing each other in tightly organized units. But the Vendeans were an enemy the Blues could not even see. To fight this way struck the regulars as dishonorable, if not downright illegal. But it worked very well for the men of the Vendée, and they were winning.

From March through May they took town after town, calling themselves at the end of that first spring La Grande Armée. Their leaders by then were drawn not only from the local nobility but from among themselves. One particularly reliable commander was a man named Cathelineau, a wool spinner and sometime mason, a married man with five children who proved not only brave but calm and cool headed in combat. Another capable leader was a gamekeeper named Stofflet, who had once been a soldier.

None of the men, or the women who sometimes fought alongside them, were professional soldiers, but they made up in valor and in numbers what they lacked in discipline. Their devotion to their religion was ardent. If they were advancing in combat along a road and came across a roadside calvary—a small shrine with a crucifix—they would kneel in prayer at it for a moment before continuing their advance, even if they were under fire. Their devotion to their homes was equally strong. During the Easter season in 1793 they deserted en masse to be with their families, returning early in April.

In May, as they were approaching Fontenay-le-Comte, the district capital of Lower Poitiers, they melted away again to tend to their planting, reducing their force to a mere 10,000. Cathelineau had to go out personally, almost house to house, to get them back. Within days he had collected 35,000, who—without cannons and some even without any weapon at all—overran the Blues defending Fontenay. In a letter written at the time, a government representative named Goupilleau tells a friend, “[Paris has] persisted, in spite of all we can say, in treating this war as a simple insurrection. I tell you that it is a volcano which will terrify the whole Republic if it is not extinguished.”

One feels for the government officers. They knew that, as one historian put it, “the Committee of Public Safety [the Jacobin rulers in Paris] recognized one proof alone of fidelity—success.” But they had few seasoned soldiers in their battalions, and none who knew anything about the tactics being used by the Vendeans. Many of the troops were raw recruits. Many had also been infected by the virus of the revolution’s egalité motto and openly questioned or criticized their commanders, as if an army were a town meeting.

That May, Pierre Quétineau, the brevet lieutenant colonel in charge of the Blues defending the sizable town of Thouars, desperately wrote the Council of Defense at Tours that three columns of Vendeans were approaching, each of 10,000 to 12,000 men, “as ardent and brave as mine are lukewarm and indifferent.” Quétineau had only 3,000 such indifferent troops, and after 11 hours of fighting, the town surrendered. Quétineau lost his head to the Jacobin guillotine for his failure. In the paranoid minds of the republican leadership, the colonel’s failure could only mean that he was secretly in league with the rebels and part of some vast conspiracy to bring them, the only true avatars of liberté, down.

BY JUNE 1793 THE INSURGENTS of the Vendée controlled most of their own territory. But what then? They could not conquer all of France, nor did they aspire to. They could not restore the monarchy, nor was there any way to make a separate peace with the central government or to exempt themselves from the law of the land, especially from conscription into the army. Secession was out of reach. Their war was defensive from the beginning; they mostly just wanted to be left alone, to live their lives as they had always lived them. But in a revolution like the one that had swept France, being left alone wasn’t possible. In a revolution, it isn’t just your body that is required, it is your soul.

For the Vendeans, the beginning of the end of their uprising came when they turned their eyes north, across the Loire into southern Brittany. They had been promised the arrival of a British fleet and émigré French nobility leading an army that would join them and mount a campaign to take back France for the monarchy. Accordingly, the bulk of the Vendean force—25,000 led by the young nobleman la Rochejaquelein, barely in his 20s—crossed the Loire in October 1793, headed toward the port city of Granville. But Granville was well defended, they found, and the promised fleet never arrived, so the rebel army was unable to take the city. Strung out in southern Brittany, in retreat and pursued by the Blues, the Vendeans lost their cohesion and their luck. On the wrong side of the Loire, they could not melt away into their homes as they had in the past. They died by the thousands before they reached the Vendée, mostly from hunger and disease. The rest of their army, still in their home territory, lost a key battle for Cholet that October. Together, the two failures delivered a devastating blow. The Vendeans would never be strong again.

That winter the Committee of Public Safety decided to “pacify” the region permanently. They called it Vendée-Vengé, the Vendée Avenged, and the general put in charge of it, Louis-Marie Turreau, was ordered to “eliminate the brigands to the last man.”

What ensued has been argued over by French historians of the left and right for generations. Even now, it is still a hot issue in French historiography. To those on the right, it was the first modern genocide, an attempt to destroy without mercy an entire region and its population, and to the Catholic Church it remains a vivid example of persecution and martyrdom. But defenders of the revolution’s policies claim that the numbers of Vendeans killed have been grossly exaggerated. The records are not so reliable as to make those arguments moot, but there can be no question of the brutality involved.

Turreau—supplied with adequate troops, many of whom were more seasoned than the earlier Blues fighting in the region—formed 12 columns. These colonnes infernales, columns from hell as they were nicknamed, drove on the region with strength. They still met resistance, and Turreau wrote about it in his memoirs, complaining in particular about the countryside they had to fight in:

How can a line of battle be instantly formed, the distances measured with the eye, the advantages and disadvantages of a forced position hastily taken be calculated, that of an enemy known, their projects foreseen, their position understood by a quick perception, like that occupied by your army, when frequent undulations of land, hedges, trees, and bushes, which obstruct the surface, will not admit of your seeing fifty paces around you?

As to the soldiers he was fighting, they used “a peculiar tactic, which they know perfectly how to apply to their position and local circumstances….Their attack is a dreadful, sudden, and almost unforeseen irruption, because it is very difficult in the Vendée to reconnoiter well, to get good information, and, consequently, to ward against a surprise.”

Yet Turreau had the manpower to overcome the guerrilla warfare, and the result in the end was monstrous. His 12 infernal columns not only penetrated what remained of the Vendée’s defenses but destroyed everything in their path. They burned farms, crops, and forests, and killed every man, woman, and child they came across, along with livestock. Paris had told Turreau to eliminate all Vendeans, and he tried hard to meet that goal. In the north priests and residents of the area were stripped—clothes were booty of war to the soldiers—then tied to rafts in the Loire that were designed to sink. Thousands drowned on those rafts. In the towns thousands more died, some by the guillotine; in Saint-Florent alone 2,000 Vendeans were massacred. One of the most extreme of the Jacobins, Louis Antoine de Saint-Just, had said that “the republic consists in the extermination of everything that opposes it.” In the Vendée-Vengé that sentiment prevailed. One republican general, François-Joseph Westermann, reported back to the Committee of Public Safety, “Following the orders that you gave me I have crushed children under the feet of horses, massacred women who at least…will engender no more brigands. I have no prisoners with which to reproach myself.”

Estimates of the numbers killed in the Vendée vary greatly, from as few as 40,000 to as many as 600,000. What is important is that the campaign was systematic, genocidal: One Jacobin suggested to a chemist that they use gas; another proposed poisoning all the wells.

Sporadic rebellions continued in the Vendée among survivors of the genocide for years thereafter, until the Jacobins themselves, having seen many of their own compatriots go to the guillotine, made a deal with the Vendeans: They would be granted liberty of worship and their property rights would be guaranteed if they would stop rebelling. But wounds like those sustained in the Vendée uprising are remembered for centuries. In one current Internet guide to the region, the author notes that anyone who moves into the area from Paris can expect to have his house burgled in the first week. To Vendeans, he says, this is “a matter of duty.” The duty never to forget.

Anthony Brandt has written for many national magazines and is the editor of the National Geographic Society’s edition of the journals of Lewis and Clark. His most recent book is The Man Who Ate His Boots: The Tragic History of the Search for the Northwest Passage.