By month’s end in June 1862 a Confederate general loathed for having lost what soon became West Virginia was being lauded as the “Savior of Richmond.” Indeed, General Robert E. Lee had accomplished the seemingly impossible by repeatedly defeating Union Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s invading Army of the Potomac in battle on the Virginia Peninsula and repelling it from the gates of the Confederate capital—all within six days. On the seventh day, however, Lee’s counteroffensive ground to a halt at Malvern Hill, overlooking the James River.

The overcautious McClellan, under the delusion Lee’s forces far outnumbered his own, beseeched Washington in vain for reinforcements. Instead, he was ordered to withdraw by ship to northern Virginia. The Peninsula campaign was over. With Lee in pursuit, McClellan needed to set up a defensive line while his army retreated to Harrison’s Landing on the James. He chose to make his stand on Malvern Hill with 54,000 men against Lee’s 55,000.

He’d selected a strong defensive position. To assault the Union lines, the Rebels would have to cross open ground and attack uphill, as creeks on either side made flanking maneuvers impracticable. Lee decided his best option was to subject Union forces to an artillery crossfire while his infantry launched a head-on assault.

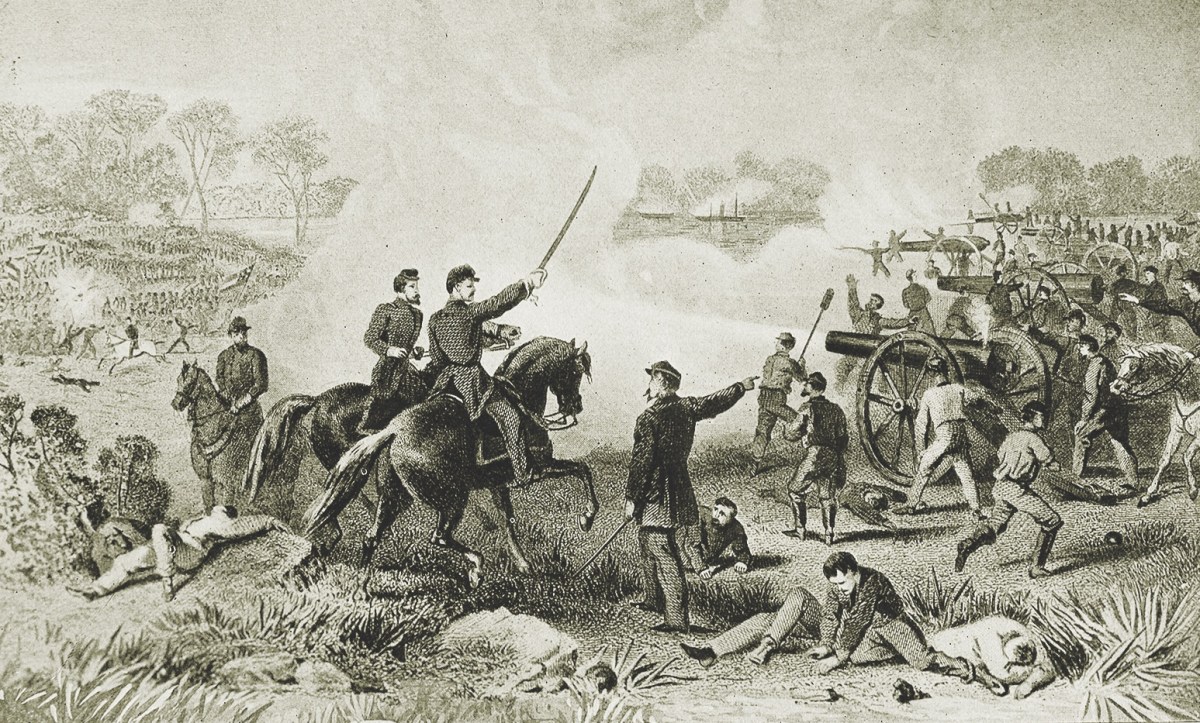

Around 1 p.m. on July 1, as Confederate forces moved into position, Union artillery opened fire. The Rebels responded with crossfire from batteries on either side of Malvern Hill. But their bombardment was poorly coordinated, and for most of the battle only one Confederate battery was active at a time. Concentrated Union fire reduced several of those in turn.

Unfortunately for Lee, his infantry was as poorly coordinated as his artillery. As many Confederate units arrived late in the day, their orders did not reflect current conditions. That led to several separate attacks instead of a single decisive assault.

After an abortive charge on the Rebel right directed by Brig. Gen. Lewis Armistead, Maj. Gen. John Magruder launched the first concerted Confederate charge, which Union gunners also met with withering fire. His men fell back.

Earlier in the day Lee’s chief of staff, Col. Robert H. Chilton, had ordered a general charge, to be signaled by a yell from Armistead’s brigade. But Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill, at the Confederate center, had heard no such yell when Armistead’s men attacked. Hill held his position. Around 6 p.m. he heard a commotion on his flank. Thinking that was Armistead’s signal, he launched his assault. Unfortunately, dense woods and fences on the line of attack split his division into five smaller waves. Like Magruder’s men before them, Hill’s isolated units ran smack into a wall of Union canister shot and fell back.

Lee ordered more assaults late in the day, but none achieved notable success. By the time night fell, so had 5,650 Southerners. Northern casualties numbered around 3,000. Lee might have logged another victory at Malvern Hill, but poor planning and disastrous communication doomed his Army of Northern Virginia. McClellan wasn’t present to celebrate, having ridden out the battle aboard a gunboat on the James.

Choose your ground carefully. A withdrawing force is usually able to choose where to stand. Exploiting that advantage, McClellan selected an excellent defensive position.

Support your infantry assaults. Lee’s frontal assaults went largely unsupported by artillery fire, allowing Union gunners to rain down canister shot on advancing Rebels.

Command can be thankless. While McClellan prevailed at Malvern Hill, and the subsequent Union withdrawal went well, his reputation was forever tarnished by the Peninsula campaign’s overall failure.

This feature originally appeared in the May 2020 issue of Military History magazine. To subscribe, click here.