The crushing victory by Japan’s battleships over their Russian adversaries at the May 27–28, 1905, Battle of Tsushima had a profound effect on Japanese maritime strategy. Tokyo’s senior naval planners believed that any future sea war would culminate in one grand battle involving the respective opponents’ largest and most heavily armed and armored battleships—a belief that persisted despite the proliferation of the aircraft carrier in the 1920s and ’30s.

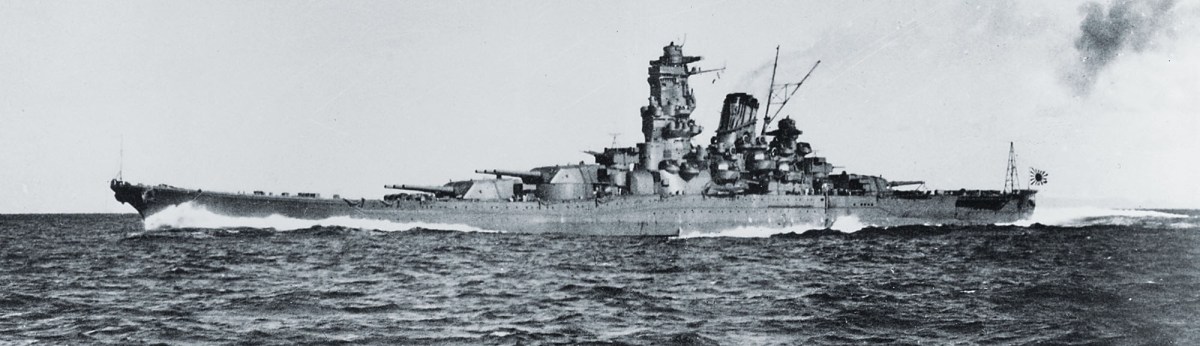

The nation’s quest for bigger and better warships led to the commissioning of Yamato and Musashi in 1941 and 1942, respectively. With a full-load displacement of 72,000 tons—nearly one-third of which was armor—and nine 18.1-inch main guns, the massive Japanese vessels were the largest battleships ever constructed.

Despite the ships’ fearsome potential, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) was reluctant to send Yamato or Musashi into harm’s way. The former was Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto’s flagship during the battle of Midway but saw no action, and Musashi returned the admiral’s ashes to Japan after U.S. P-38 fighters shot down his aircraft over Bougainville on April 18, 1943. American submarines damaged both battleships with torpedoes, but neither ship fired its guns in anger until the October 1944 Battle of Leyte Gulf.

By then the Allies had largely neutralized Japanese naval airpower, and on October 24 multiple waves of U.S. carrier-based aircraft targeted Musashi. Poor coordination by the attackers allowed the battleship to survive longer than it might have, but hits by 19 torpedoes and 17 bombs ultimately sent Musashi and 1,023 of its 2,399-man crew to the bottom. Yamato survived Leyte and outlived its sister ship by more than five months, though it finally succumbed to better-orchestrated U.S. air attacks on April 7, 1945, while engaged in Operation Ten-Go, an attempt to counter the American landings on Okinawa. Some 3,000 of Yamato’s 3,332-man crew died with their ship.

Flawed strategy sinks ships. The IJN’s persistent belief the air- craft carrier would be an auxiliary vessel to big-gun vessels—in spite of their own carrier successes—led to the loss of both super battleships.

Even the most powerful obsolete weapon remains obsolete. Though Yamato and Musashi were the most powerful battleships ever built, advances in naval airpower had negated their significance.

Practice makes perfect. It took 36 hits to sink Musashi but fewer than 20 to send Yamato to the bottom.

If you have it, use it. Yamato and Musashi saw virtually no action until the final year of the war. Used earlier, they might have tipped the naval balance in the IJN’s favor, possibly altering the outcome of the Pacific war.

Look to the sky. The IJN never developed adequate anti-aircraft protection for its ships. What guns they did have were often inaccurate and lacked the range and stopping power to shoot down late-war American strike aircraft like the Helldiver and Avenger.

Use resources wisely. The Yamato- class battleships consumed more than 140,000 tons of steel and other materials that were hard to come by even in prewar Japan. The metal used on both ships could easily have supplied the Japanese with a half-dozen more carriers and the aircraft to operate from them.