The Western Confederate Army never recovered from Albert Sidney Johnston’s April 1862 death at Shiloh

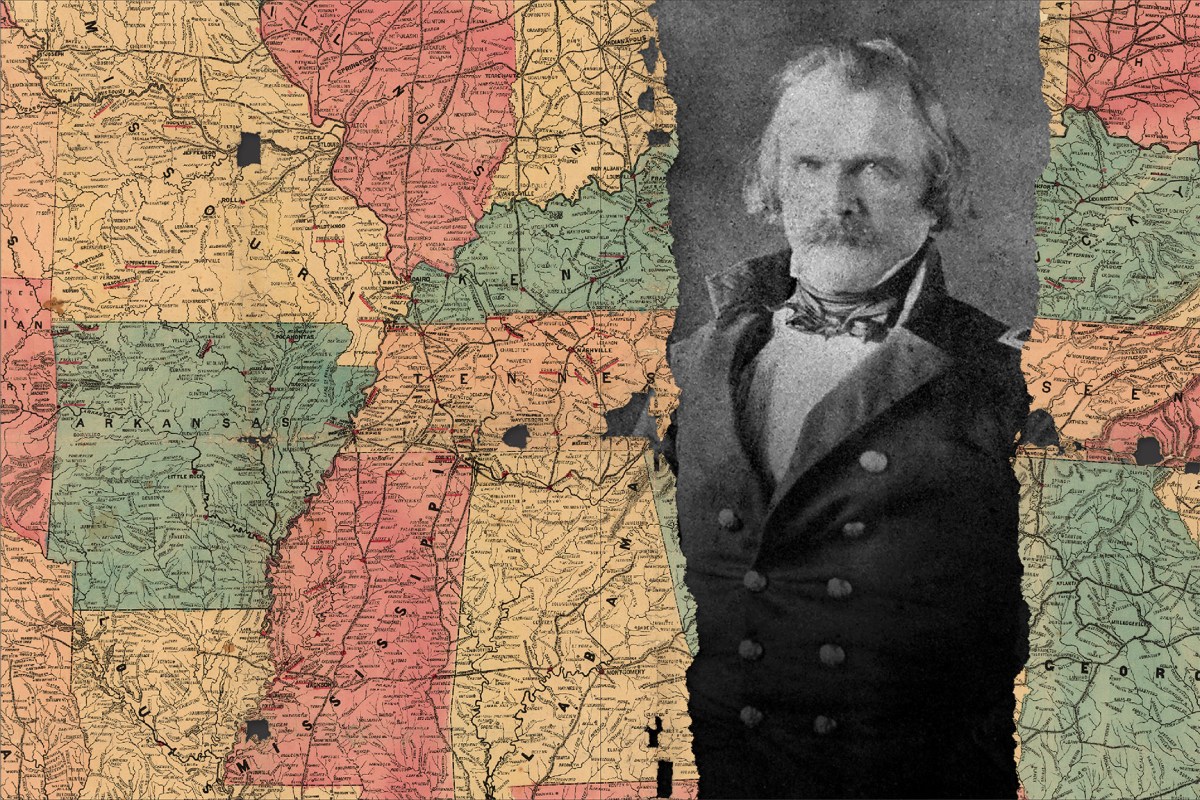

General, are you wounded,” Isham G. Harris frantically asked as Albert Sidney Johnston slumped in his saddle about midday April 6, 1862. At dawn, Johnston’s Army of the Mississippi had launched a surprise attack on the Union Army of the Tennessee near Pittsburg Landing, Tenn., but seemingly little had gone right since. The Confederates took about six hours to completely break through the initial line of Union camps, defended by less than half of Ulysses S. Grant’s army, before slamming into the bulk of the Federal force—comprising veterans who put up a stiff fight across the battlefield. As Johnston’s army tried to turn the Union left, the storied commander realized the attack had stalled and rode east to give the effort his personal attention. He succeeded in getting the assault moving again, but his aggressiveness would cost him his life. Shot in his right leg, his popliteal artery severed by a Minié ball, Johnston bled to death within an hour.

In response to Harris’ inquiry, Johnston could only mumble, “Yes, and I fear seriously,” before beginning to lose consciousness. Harris, the governor of Tennessee who was serving as Johnston’s aide, and another staff officer led the general’s horse down the hill and out of the line of fire in an attempt to save him. The two laid Johnston at the foot of a tree and began searching for a wound in his torso before discovering the gash on Johnston’s leg. Soon Johnston was unable even to swallow the whiskey administered to him, as it merely gurgled in his throat. At 2:30 p.m., he was gone, the highest-ranking American military officer ever killed in action in U.S. history.

Johnston had considered the Battle of Shiloh the moment at which he and his army must “conquer or perish.” The consequences of his death have been debated ever since, and, correctly, most of the debate has centered on its effects on the battle’s outcome. Had Johnston lived, many continue to argue today, Shiloh would have been a Confederate triumph. When he perished, the Confederate cause figuratively perished, too.

Leading that argument was Johnston’s son, William Preston Johnston, who maintained that his father would have continued strikes on Grant’s rattled army and would not have called off the attacks, as did his replacement, General P.G.T. Beauregard. William Johnston was adamant that, in doing so, Beauregard had thrown away his father’s victory and thus allowed Grant to grab the initiative overnight and win the battle on April 7.

Historian Charles P. Roland echoed that argument in his highly regarded biography, Albert Sidney Johnston: Soldier of Three Republics. The majestic United Daughters of the Confederacy monument at the Shiloh National Military Park, which was placed near the famed Hornet’s Nest in 1917, also leans heavily on Lost Cause dogma that Johnston’s death, along with the loss of daylight that first day of the battle, were at the crux of the Confederates’ catastrophic defeat.

More recently, historians have split on whether Johnston’s death made any real difference in the battle’s outcome, some emphasizing that a “lull” in the battle occurred at the time of the general’s death and others arguing that because Johnston’s army had simply wasted far too much time as darkness approached on April 6, there was little hope it would be able to regain the edge.

While it is debatable how much of a difference Johnston’s death made on the field of Shiloh itself, it was actually in the future command of the Western Confederacy that Johnston’s absence would ultimately prove most significant. Since the war, there has been extensive debate over how great a commander Johnston would have become had he not been mortally wounded—perhaps even another Robert E. Lee, who conveniently had the luxury of learning from his initial stumbles during the war before he assumed command of the Army of Northern Virginia in June 1862 and, as a result, established his place as one of this country’s greatest military leaders.

Such arguments are, of course, based in “what-if” thinking, but we do know for sure what happened in the Western Theater after Johnston was gone. Perhaps Confederate President Jefferson Davis, a Johnston admirer, said it best when he observed: “[W]hen Sidney Johnston fell, it was the turning-point of our fate; for we had no other hand to take up his work in the West.”

Davis’ statement was bold but true—at least in part. Eastern Theater supporters might take umbrage that Johnston’s death sealed the Confederacy’s fate; arguments on the respective importance of the war’s two principal theaters have raged for decades and will undoubtedly continue to do so in the future. There should be no dispute, however, that Davis was correct in his assertion that there was no other general capable of taking Johnston’s place.

Who, though, could fill Johnston’s position in the West? First considered had to be the four remaining full generals in Confederate service at the time, one of whom was Beauregard, Johnston’s second in command. After defeat at Shiloh, the Army of the Mississippi pulled back to its base at the critical railroad town of Corinth, Miss., to await the Federal command’s next move. Facing the likelihood that the Federals would follow its victory by moving on Corinth, it seemed prudent to keep Beauregard in charge of the army, at least until operations around Corinth had been decided one way or the other.

Would Beauregard, who famously led the Confederate victories at Fort Sumter and First Manassas in 1861, be a permanent solution, however? Given the 44-year-old Louisianan’s failing health at the time and the stark differences he had with both Davis and many in Davis’ administration, the answer seemed no.

In the war’s first year, there were five full generals in the Confederate Army, and in the spring of 1862, two could easily be taken out of consideration for command of the Western Army. Although Samuel Cooper was the ranking Confederate general, at nearly 64 years of age he was not a true consideration for field command, likely never to leave his desk assignment at the War Department in Richmond. Because the Confederacy’s second-ranking general had been Albert Sidney Johnston, that left Robert E. Lee, Joseph E. Johnston, and Beauregard.

The fates of Lee and Joe Johnston were intertwined in the Eastern Theater. As events transpired around Corinth in April–May 1862, Johnston and Union Maj. Gen. George McClellan had locked horns on the Virginia Peninsula. When Johnston, commanding what became known as the Army of Northern Virginia, was seriously wounded by artillery shrapnel at Seven Pines (Fair Oaks) on May 31, Lee assumed command the next day, and in the Seven Days Campaign from June 25 to July 1, he notably chased McClellan away from Richmond, saving the Confederate capital.

Earlier in the war, Lee had been underwhelming while holding commands in western Virginia and South Carolina, and during the Peninsula Campaign he was serving as Davis’ adviser. Even before Johnston’s wounding, it was unlikely Davis would assign Lee, a devoted Virginian, to command of the Western Army.

That became a moot point on June 1. Johnston would need a long time to recover from his dreadful Seven Pines wound and was, in fact, still not yet at full strength when Davis finally handed him a command in the Western Theater in December 1862. The wound would continue to bother Johnston during the ensuing Vicksburg Campaign.

It is telling that Davis did not make Johnston an army commander, and Johnston was not allowed an opportunity to be Albert Sidney Johnston’s replacement until much later in the war. Even then, because of his differences with Davis, he would command the Western army for only two brief periods—mere months—during the 1864 Atlanta Campaign and at the end of the war when his presence had no tangible impact on Confederate fortunes.

From June 1, 1862, Robert E. Lee would not relinquish command of the Confederacy’s foremost army, making it one of the country’s finest fighting forces ever. Until the surrender at Appomattox in April 1865, Lee would leave Virginia only twice, on his two ill-fated invasions of the North in September 1862 and the summer of 1863.

With Albert Sidney Johnston dead, Joe Johnston incapacitated, Lee committed elsewhere, and Cooper relegated to desk duty, a reluctant Davis had to count on Beauregard to defend Corinth in the face of a Federal threat after the loss at Shiloh. Beauregard messaged Richmond that “if defeated here, we lose the Mississippi Valley and probably our cause.” On May 30, however, the Louisianan evacuated Corinth without a fight.

That decision was unquestionably the right one. Although the Federals had moved cautiously against the Corinth defenses and “siege” operations didn’t begin until May 27, the odds were clearly on their side. Having lost hundreds of soldiers to illness, Beauregard’s army was significantly outnumbered.

Nevertheless, losing Corinth in that manner only magnified Davis’ suspicions about Beauregard’s abilities. It did not help Beauregard’s case either when he opted to leave the army without authorization in order to tend to his weak health. On the authority of his surgeon, Beauregard traveled to a springs resort in Alabama, and when Davis learned of the commander’s whereabouts, he exploded in anger, immediately removing him from command. Beauregard would not tactically command another major army the rest of the war.

To find a suitable replacement for the vacancy, Davis now had to resort to the next tier of generals. That created more chaos. The crux of the problem was the needed elevation of one of many equals to the command of former colleagues. In the West, that category included Leonidas Polk, Braxton Bragg, William J. Hardee, and John Breckinridge, all Army of the Mississippi corps commanders at Shiloh. Undoubtedly, these generals inwardly believed they would do better than the others. Johnston and Beauregard had been full generals, and Polk, Bragg, Hardee, and Breckinridge accepted serving under both, choosing not to buck the army’s traditional chain of command and giving them the necessary respect.

The ranking corps commander, and hence the general of the army’s first numbered corps, was Polk. He outranked the next ranking corps commander at Shiloh, Bragg, by 2½ months. Making the situation even more tense, Bragg outranked the next corps commander in line, Hardee, by a mere 3½ weeks.

Breckinridge, the fourth commander, was still a brigadier general at Shiloh, and despite serving as secretary of war later in the war, he was never really considered as a replacement for Johnston. Because he was also a former U.S. vice president—James Buchanan’s second—he still had plenty of clout.

Davis could also have considered the top two generals in the Trans-Mississippi Theater, Sterling Price and Earl Van Dorn, but the prospects for both were basically the same. Price did not become a major general until March 1862, a month before Shiloh; Van Dorn outranked Hardee, but was behind both Polk and Bragg in seniority. Significantly, and complicating the situation even more, both Van Dorn and Price had commanded armies in the Trans-Mississippi: Price at Wilson’s Creek, Mo., and Van Dorn at Pea Ridge, Ark.

Only Polk among the original Shiloh corps commanders had been an army commander earlier in the war. But the Army of the Mississippi was a much different animal now than those smaller Trans-Mississippi armies, which took Van Dorn and Price out of the picture.

By right of rank, the position as Johnston’s replacement should have gone to Polk. But he didn’t get the call. Neither did Hardee, who had served reputably in the antebellum U.S. Army and was the author of its famed Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics manual. It quickly became evident that the anointed one was Bragg, who actually had been promoted to full general immediately after Shiloh, although he remained under Beauregard’s command.

Polk and Hardee were both promoted to lieutenant general in October 1862—as were Stonewall Jackson and James Longstreet back East—but, considering themselves Bragg’s equal, continued to balk at his promotion above them. That sharp reaction continued to fester throughout Bragg’s tenure as commander of what was now the Army of Tennessee over the next 18 or so months.

This period is often seen as one of the most critical eras of the Western Confederacy’s existence. Some argue that the war in the West was lost by Shiloh; others argue it came with the fall of Atlanta in the charged geopolitical year of 1864. Still, one would be hard pressed to find a more critical period in the West than Bragg’s tenure from June 1862 to December 1863, which would encompass the Kentucky (Perryville), Stones River, Tullahoma, Chickamauga, and Chattanooga campaigns.

With the fate of the entire Confederacy arguably on the line, the new commander needed all the support he could get from his subordinates. The next 18 months, however, were a disaster for both Bragg and the Confederacy, largely because of the back-biting of Bragg’s former equals-turned-subordinates. Other anti-Bragg generals emerged—foremost James Longstreet, D.H. Hill, Simon Boliver Buckner, Frank Cheatham, and Nathan Bedford Forrest. Yet it would be difficult to find three more bitter Bragg enemies than Polk, Hardee, and Breckinridge.

Bragg would note that his efforts were “most distasteful to many of my senior generals, and they wince under the blows. Breckinridge, Polk & Hardee especially.” While none stooped to the dishonor of claiming publicly they would be a better choice than Bragg, each lapsed into acidic relations with the commander and by all historical accounts disobeyed, undermined, and conspired against him.

Initially, despite his political clout, Breckinridge was the one perhaps least concerning to Bragg. Nevertheless, rancor between the two began to develop as early as the Kentucky Campaign and remained a concern until both left the army after the fall of Chattanooga in November 1863. In fact, while defending himself and his beloved Kentuckians to the hilt, Breckinridge usually tried to diffuse the situation when he could and apparently never worked against Bragg. That said, his preference for defensive tactics were counter to his commander’s battle philosphies.

Outwardly, Hardee seemed the most agreeable of the trio toward Bragg, preferring to work clandestinely and on occasion conspiring with Polk and others to remove him. Like Breckinridge, Hardee’s troubles with Bragg began during the Kentucky Campaign. At one point, he wrote Polk: “I have been thinking seriously of the condition of affairs with this army….What shall we do? What is best to be done to save this army and its honor? I think we ought to counsel together.” And Bragg was certainly convinced Hardee wanted his spot, writing to a friend of his potential “retirement”: “I must say there is no man here to command an army. The one who aspires to it is a good drill master, but no more, except that he is gallant.”

Polk’s hostility toward Bragg could be traced back to Shiloh and had evolved into open antagonism by the time of the Kentucky Campaign, continuing to balloon from there. Until he left the army at Bragg’s insistence, Polk continually sought to undermine and conspire against the commander. Significantly, much of the conspiring came in letters about Bragg written directly to President Davis, who was Polk’s friend. Writing to a friend after he left the Army of Tennessee, Polk declared: “[T]he poor man who is the author of this trouble is I am informed as much to be pitied or more than the object of his ill-feeling. I certainly feel a lofty contempt for his puny effort to inflict injury upon a man who has dry nursed him for the whole period of his connection with him and has kept him from ruining the cause of the country by the sacrifice of its armies.”

On one occasion, Bragg provided a fairly accurate assessment of Polk, complaining to Davis: “Genl. Polk by education and habit is unfitted for executing the plans of others. He will convince himself his own are better and follow them without reflecting on the consequences.”

In examining these fights with his subordinates, it can’t be ignored that the majority of the issues usually came about because of Bragg’s disparaging personality and not so much because of instigation by these commanders (not that that didn’t occur regularly, as discussed above). Certainly, most of the bitterest quarrels, especially with Breckinridge, resulted from Bragg’s pushing rather than by his subordinates’ conspiring.

Bragg did not help himself either by continually seeking the approval of his subordinates, even going so far to ask whether the army still had confidence in Bragg’s leadership. All three answered with a resounding no. Each plainly let Bragg and others know that they felt Bragg was not capable of commanding the army. Hardee, for example, wrote a blistering response: “I feel that frankness compels me to say that the general officers, whose judgment you have invoked, are unanimous in the opinion that a change in the command of this army is necessary. In this opinion I concur.”

Of course, such criticism filtered down to subordinate commanders, many of whom also quickly lined up against Bragg. Others certainly defended Bragg, but the polarization of the Army of Tennessee’s high command was a huge impediment to its efficiency, and the doleful record of the army throughout Bragg’s important tenure (in casualties, missed opportunities, and lost territory) was a firm byproduct.

There is no way to know if Albert Sidney Johnston, had he lived, would have performed better than Bragg facing similar campaign scenarios, or if any of the other full generals would have either. Yet the reality is that, for Davis, none was a good option. Davis truly believed, “we had no other hand to take up his work in the West.” Johnston’s loss thus left the Western Confederacy’s primary army in the hands of a general tasked with leading former command equals, and, as discussed above, the situation deteriorated quickly. And it only became worse after Bragg’s tenure, with Davis having to settle out of necessity for Joe Johnston (whom he considered an unacceptable option) and then John Bell Hood (a truly untried and unproven army commander, who quickly showed how untried and unproven he was).

By that time, events in the Confederate West had degenerated too far to make a difference in the Southern Army’s prospects for winning the war. The snowball effect of that started rolling that mild day in April 1862 when Albert Sidney Johnston, and perhaps the Confederacy itself, perished rather than conquered at Shiloh.

Timothy B. Smith, Ph.D., a veteran of the National Park Service, teaches history at the University of Tennessee at Martin. He is the author, editor, or co-editor of 20 books, including award-winners Champion Hill: Decisive Battle for Vicksburg (2004); Shiloh: Conquer or Perish (2014); and The Real Horse Soldiers: Benjamin Grierson’s Epic 1863 Civil War Raid Through Mississippi (2018). A resident of Adamsville, Tenn., he is writing a book on the 1863 Siege of Vicksburg.