The year 1870 was a time of war on the northwest Texas frontier. Kiowa and Comanche raiders striking out of the vast southern Plains punished the line of Anglo settlement as it inexorably pushed its way north and west. The Indians felt compelled to lash out, given renewed postwar encroachment into their lands, unfair or broken treaty agreements, the impending specter of forced reservation life and their own intertribal politics. The U.S. Army was likewise compelled to maintain peace and safety for its citizens on the Texas frontier.

For 15 years one of the hottest spots in this unrelenting contest was sparsely populated Jack County, up near the Red River in north-central Texas. Settlers there were usually the first to suffer with the coming of each full moon, and their protests and cries for protection had resulted in 1868 in the establishment of a military post, Fort Richardson, on the outskirts of the county seat, Jacksboro. If the settlers thought their problems were solved, however, they were soon bitterly disappointed.

Fort Richardson became the headquarters of the 6th U.S. Cavalry, a regiment that boasted a far thicker record of desertions than of Indian fights. Over its 39-month tenure at the fort the regiment sent out 26 full-scale scouting parties, but only five intercepted Indian raiders, resulting in the deaths of three troopers and unknown casualties to the warriors. During that same period Indian raiders killed or captured more than 200 settlers and drove off thousands of head of livestock. The 6th seemed powerless to prevent such depredations. The carnage reached a crescendo in June 1870 when raiders killed another 15 settlers. Letters, protests and petitions flew from the pens of the settlers to both the officers at Fort Richardson and the government in Washington, D.C. How could the vanquishers of the Confederacy be so ineffective against a few hundred poorly armed Indians?

Aggravating the situation was the fact that in the wake of the Civil War, Washington had forbidden the re-formation of the Texas Rangers, the one group that had had some success against the southern Plains Indians. Stung by the continual criticism and charges that soldiers trained only for the parade ground were no match for veteran warriors adept at guerrilla warfare, the officers of the 6th waited and watched for any opportunity to restore their honor and morale in the ranks.

Whether they were ready or not, opportunity came knocking.

“A Galling Fire from All Sides”

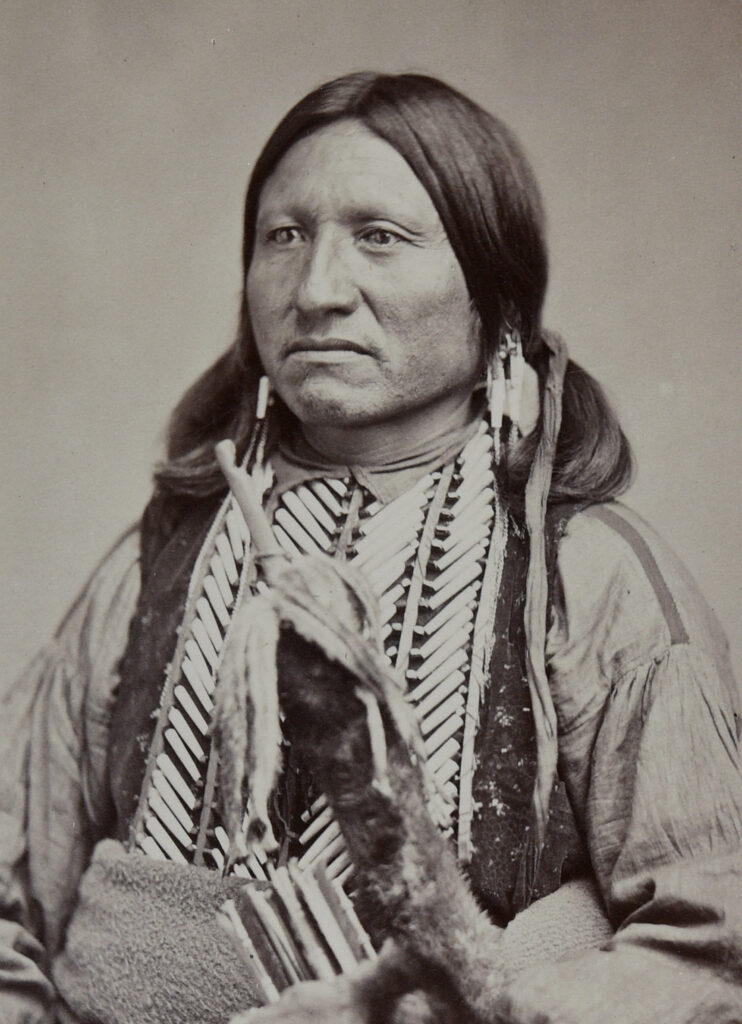

In early July a party of more than 100 Kiowa warriors crossed the Red River into Texas from Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). It was led by Kicking Bird (or Eagle Striking With Talons, as his name has been translated more recently), among the best-known war leaders on the southern Plains. Long distinguished among the Kiowa for his courage and military prowess, he was also a signatory of both the 1865 Little Arkansas Treaty and the 1867 Medicine Lodge Treaty. He even had admirers among the Anglos. “Though a wild, untutored savage,” one Indian agent wrote of the chief, “he was a man of fine native sense, and thoroughly educated in the habits of his people, and determined to make a reputation for himself, not in bad acts, but in elevating his people.” Kicking Bird was perhaps second in influence only to the acknowledged principal chief, Lone Wolf.

In more recent years, however, Kicking Bird had spoken once too often of seeking peaceful accord with the whites, prompting the more radical elements among the Kiowa to question his abilities and fitness to lead. Some warriors went so far as to claim that his consorting with white men had made him a coward and a traitor. To restore his honor, Kicking Bird agreed to lead a major war party against the white soldiers, and the men of Fort Richardson were selected as the target, mainly because they were the only force in north Texas opposing the southern Plains Indians.

According to Indian participants interviewed in the 1920s at Fort Sill, Okla., by Colonel Wilbur Sturtevant Nye, no warrior was supposed to leave the war party to steal. Yet, on July 5 a handful of Kiowas attacked a mail wagon at Rock Station, 16 miles west of Fort Richardson. A challenge to the Army thus delivered, the 6th Cavalry quickly responded. At the head of two officers, one surgeon and 53 enlisted men culled from six companies of the 6th, Captain Curwen B. McLellan led out his men on July 6 with orders to “pursue and severely chastise the Indians.”

Born in Scotland, McLellan (no relation to Union commander Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan) was a veteran of the Civil War. Commended for his bravery and tactical skill at Gettysburg, he’d received a brevet promotion to major, only to revert in rank to captain amid the general postwar reduction of the Army. It would seem fate had chosen a worthy opponent for Kicking Bird.

At Rock Creek Station scouts picked up the trail of eight to 10 Kiowa warriors. Slowed by heavy rains and rough terrain, the column followed the trail northwest, McLellan assuming the raiders intended to slip across the Red River into Indian Territory, where, by federal edict, the troopers were forbidden to follow. Only, this band of Indians had no intention of fleeing. On the contrary, the captain and his men were being drawn into an ambush on ground of Kicking Bird’s choosing.

McLellan’s error is understandable. Like most Civil War officers, he’d been trained and disciplined to fight 19th century set-piece battles. But such an approach could only end in frustration on the frontier, as Plains Indians were seldom willing to engage in straight-up fights. Instead, they relied on their advantages of surprise and mobility, employing mostly hit-and-run tactics before withdrawing to their Oklahoma reservations as an untouchable home base. Thus, many Army officers had come to regard patrols sent in pursuit of Indian raiders as mere exercises in herding the hostiles back across the Red River, dismissing warnings of the Indians’ skill in preparing ambushes. McLellan would pay dearly for such a miscalculation.

On July 9 the captain resumed his march northwest to the headwaters of the South Fork of the Little Wichita River, where his scouts found the mail wagon driver’s whip and an indistinct trail leading west. Continuing northwest past the headwaters of the Middle Fork, McLellan and his men soon reached a bluff on the south bank of the North Fork. As the heavy rains had obscured all signs of the raiders’ ponies and rendered the North Fork impassable, McLellan ordered his men into camp, where they remained until July 12.

Around 11 that morning, an hour after decamping, the advance guard encountered what appeared to be a Kiowa scouting party. Anticipating that the main body of Indians was nearby, McLellan had his troopers form ranks, unfurl their banners, unsling their weapons and advance at a quick trot, soon outstripping the column’s packtrain, loaded with ammunition and supplies. After covering about a half mile, the troopers spotted a large band of Kiowas some 1,000 yards distant. McLellan had found Kicking Bird—or, rather, Kicking Bird had allowed himself to be found. The captain had closed within 500 yards of the Kiowas when two other bands, together equaling the first in strength, popped up on his flanks, threatening to cut off his packtrain and rear guard, which had fallen some 400 yards behind. Realizing he could no longer safely move forward, McLellan ordered his troopers to open fire.

At that point Kicking Bird ordered a full-scale charge on three sides. The Kiowas attacked with a ferocity for which the troopers of the 6th were unprepared. Years later warriors who participated in the battle reported that Kicking Bird rode at the head of his men and counted first coup by impaling a soldier on his lance. Surely McLellan would have reported such a dramatic action, yet there is no mention of it in his after-action report. Embarrassment is one possible explanation. That an Indian could ride into the face of more than 50 professional soldiers, kill one with a lance and slip away unscathed would be a distressing event. Whether it happened or not, the Kiowas clearly had the upper hand. For a half hour the troopers endured what McLellan called “a galling fire from all sides,” at which point it became apparent the command was in danger of being overrun. It must have dawned on the captain how far he had ventured from any defensible position or any possible help—in other words, how perfect the battlefield was for Kicking Bird.

The pursuer had become the pursued. McLellan realized that the only way to preserve his command from “total annihilation” was to retreat.

Desperate Retreat

McLellan dismounted his men, every fourth trooper holding the reins of the mounts while the other three fired between the horses. They formed a box around the packtrain, with roughly 10 men to a side and a 10-man reserve in the middle, and began to effect what McLellan described in reports as “an orderly withdrawal,” but which in truth was a desperate fight for survival. Many of the Indians were armed with Spencer repeating rifles, which complemented their mounted tactics perfectly. The men of the 6th were using the single-shot breech-loading Springfield trapdoor carbine, a weapon with a comparatively slow rate of fire, though it could send a bullet up to 400 yards downrange with accuracy and power. As a result, the Kiowas kept their distance, swarming first around one flank and then another, several times forming up to block the troopers’ line of retreat. McLellan frantically redeployed his men to meet each threat that arose, but his casualties were mounting and his ammunition waning. For some four and a half hours under a hot July sun Kicking Bird mercilessly drove the 6th Cavalry over the plains and back down across the North and Middle forks of the Little Wichita, pouring a constant and devastating fire on the bluecoats from all sides.

Kicking Bird maintained a strong, steady pursuit by keeping three-fourths of his men engaged while holding the others in reserve, then steadily replacing tired warriors with fresh ones from the reserve. The unrelenting stream of strikes by seemingly tireless Indians surprised McLellan and his officers, who found it all they could do to hold their own while retreating.

Around 4 p.m. the captain and his exhausted troopers forded the South Fork of the Little Wichita, at which point Kicking Bird called for his warriors to abandon the pursuit, confident his honor had been restored. The Kiowas had killed or wounded nearly a quarter of McLellan’s command and nearly half his horses.

Though no longer under fire, McLellan felt his position remained untenable, so he ordered his men to continue the southeasterly retreat toward Fort Richardson. Ultimately, however, sheer mental and physical fatigue forced the 6th Cavalry into camp within sight of Flat Top Mountain.

Early the next morning, July 13, McLellan dispatched couriers to Fort Richardson, requesting ambulances for the wounded. But his intention to remain encamped until the ambulances arrived was thwarted when a band of several dozen Kiowas attacked and drove in the pickets. Fearing that Kicking Bird’s entire war party was close at hand, the captain ordered all supplies burned and his weary men to saddle up the remaining horses and begin another forced retreat. After resting a few hours at Rocky Station, the scene of the attack on the mail stage a week prior, the command continued southeast toward Fort Richardson. Meeting the ambulances en route, the battered column went into camp that night, arriving back at the garrison at noon on July 14.

Saving Face

In his after-action report McLellan listed two men killed and 11 wounded, and eight horses killed and 21 wounded. Though he had obviously suffered a humiliating rout, the captain estimated far higher enemy losses, claimed the expedition had been a “perfect success” and insisted he had “taught them a lesson they will not soon forget.” A far less rosy assessment was reported by his troopers, however, many of whom were incensed that McLellan had abandoned the two slain enlisted men’s bodies during his retreat.

In the aftermath Fort Richardson post surgeon Dr. Julius H. Patzki interviewed members of the command. One constant in his report was the emphatic bafflement of troopers to the overwhelming demonstration of military skill by Kicking Bird and his warriors. “The systematic strategy displayed by the savages, exhibiting an almost civilized mode of skirmish fighting, struck the officers and men engaged,” Patzki wrote. It was a compliment McLellan could never pay Kicking Bird.

The Army praised the captain for having kept his command from being wiped out, and 13 members of the 6th Cavalry later received the Medal of Honor for “gallantry in action at the North Fork of the Little Wichita River.” Thus, McLellan, like Kicking Bird, managed to save face.

The events along the Little Wichita served to demonstrate warriors were capable of far more cunning than their stereotypical “savage” reputation implied. Kicking Bird’s systematic and precise formations were those only the most adept tacticians are able to pull off in the heat of battle. He executed his ambush and flanking maneuvers with a striking ease that overwhelmed the rigid professional tactics of the 6th Cavalry and did so with minimal loss. Kiowa participants later insisted no warriors had been killed. That said, tribal society was highly stratified, and the loss of a low-ranking warrior might not have warranted mention in their oral history.

Kicking Bird had set out to restore his honor in action against the bluecoats, and he succeeded. Expressing regret that he’d resorted to violence, he never again rode into battle against the soldiers, instead preaching the road of peace. After the 1874–75 Red River War the Army gave him the onerous task of selecting the requisite Kiowa warriors and chiefs who would be sent to prison in Florida. Among the exiles was the powerful medicine man Maman-ti, who threatened Kicking Bird. “You remain free, a big man with the whites, but you will not live long,” he vowed. “I will see to that.” Kicking Bird had told an Anglo friend his heart was as a stone, broken in two. “I am grieved,” he said, “at the ruin of my people.” Two days later the chief died at his camp under mysterious circumstances. While some Kiowas claimed it was the curse of Maman-ti, Army doctors suspected poison.

McLellan never led another major expedition in Texas. Within nine months of its fiasco on the Little Wichita the 6th Cavalry was transferred to Kansas and replaced by a more vigorous unit, the 4th Cavalry, led by the legendary hard-charging Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie. With its arrival the people of north Texas would finally get their protection from the Indians.

Allen Lee Hamilton, a history professor at St. Philip’s College in San Antonio, is the author of six books, a novel and numerous magazine articles. His eldest son, Clinton Chase Hamilton, holds a master’s degree in history from Texas State University. For further reading they suggest Sentinel of the Southern Plains: Fort Richardson and the Northwest Texas Frontier, 1866–1878, by Allen Lee Hamilton; Carbine and Lance: The Story of Old Fort Sill, by Colonel W.S. Nye; and Forty Miles a Day on Beans and Hay: The Enlisted Soldier Fighting the Indian Wars, by Don Rickey Jr.