CAMEO

Before plotting murder, the actor tried his hand at oil

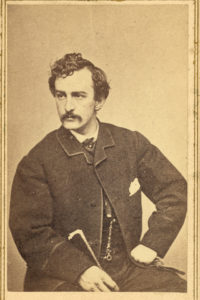

JOHN WILKES BOOTH at 24 had the charisma of a young Johnny Depp. Graceful, daring, and handsome, with flashing dark eyes, he was the youngest son of a prominent theatrical family. Father Junius Brutus Booth had emigrated from England to make his name as a Shakespearean and succeeded. Older brothers Edwin and Junius Jr. already were established thespians in 1845 when John, 17, first trod the boards. Physical vitality alone made the youngest Booth memorable, and by 1858 he was a star and a celebrity. However, in January 1864, John Wilkes Booth quit theater to seek his fortune in Franklin, Pennsylvania. In that boomtown, he strutted his hour as an oil well speculator before coming to a different notoriety for assassinating President Abraham Lincoln. Long after Booth’s death by gunshot after being cornered in a burning barn in Port Royal, Virginia, rumors swirled that Lincoln’s killer had made a fortune as a wildcatter. The truth is far different.

Raised in rural Bel Air, Maryland, John Wilkes Booth so ardently embraced the white supremacist cause that he attended the 1859 hanging of abolitionist insurrectionary John Brown at Charles Town, Virginia.

In 1863, Booth was performing in theaters up and down the Eastern Seaboard when a mysterious hoarseness took over his throat and threatened his livelihood. Whether caused by poor vocal technique or bronchitis, the condition caused Booth to book fewer appearances. After starring as Richard III in St. Louis in January 1864, he shucked theater hoping to strike it rich in oil.

(Library of Congress)

In seeking another career, Booth also was joining a wave of Americans looking to prosper on the new frontier of energy. To light their lamps, American households needed liquid fuel. To lubricate machinery, American factories needed oil. Oil came mainly from sperm whales, killed and rendered at sea. Whaling had so depleted that species that sperm oil had become costly. An alternative was a flammable glop oozing to the surface around western Pennsylvania in patches called oil seeps. Native Americans had long burned the stuff, sopping it up in blankets wrung into containers. Speculators were eyeing coal gas, camphine, a byproduct of turpentine distillation, and other fuels. However, “rock oil” not only burned well—emitting “a dainty light; the brightest and yet the cheapest in the world,” a booster said—but also was a swell lubricant.

Oil, which often seeped near salt deposits, went unexploited for lack of a practicable way to extract it until 1859, when the tenacious Edwin Drake, 59, drilled the first commercial oil well. Investors had brought the former railroad worker in on a well at Titusville, Pennsylvania. His first hole, drilled with a bare shaft, caved in, trapping the mechanism. Drake encased the shaft in a protective metal sheath. His design succeeded, proving deep drilling could work. Within a year of Drake’s strike, 500 drilling rigs were lining the 16 miles of Oil Creek between Titusville and Oil City.

“The whole population are crazy almost,” investor George Bissell wrote. “I never saw such excitement. The whole western country are thronging here and fabulous prices are offered for lands in the vicinity where there was a prospect of getting oil.”

Booth joined the oil rush, convincing two theatrical pals from Cleveland to come in as well. Their Dramatic Oil Company leased 3.5 acres outside Franklin. The wildcatters called their would-be gusher “Wilhelmina” after one partner’s wife. After a brief sojourn onstage, Booth returned to Franklin in May 1864 with banker Joseph Simonds, an acquaintance from Boston. Workers, speculators, and teamsters hired to haul oil so crowded Franklin that the two had to room with others.

Booth swanned around town, Confederate zealotry on full display; in a barbershop he upbraided a black man for wearing a hat. The man retorted that he bared his head for ladies, so outraging Booth that a companion said he was sure that if the actor had had a weapon he would have killed the fellow.

The Wilhelmina scarcely delivered, though Booth spent another couple of thousand dollars trying to improve extraction. The preferred method, a precursor to fracking, involved detonating explosives in a laggard well in hopes of dislodging oil. At Wilhelmina the tactic failed and ruined the well. In September, Booth gave his stakes to family and to Simonds. Booth headed to Baltimore, then to Montreal, where he mingled with fellow Confederate sympathizers before relocating to a frequent stop, Washington, DC.

In February 1865 the actor sent Simonds a note the banker found disturbing. “I hardly know what to make of you this winter—so different from your usual self,” Simonds replied. “Have you lost all your ambition or what is the matter. Don’t get offended with me John but I cannot but think you are wasting your time spending the entire season in Washington doing nothing where it must be expensive to live and all for no other purpose beyond pleasure. If you had taken 5 or 10,000 dollars and come out here and spent the season living here with us, traveling off over the country hunting up property I believe we both could have made considerable money by it. It is not too late yet for I believe the great rush for property is to be this Spring ….”

Simonds was right. Lack of efficient transport was bottlenecking the oil flow. In less than a year the industry began building pipelines, dramatically widening markets but also stirring unrest as sidelined teamsters fought the new technology. Thanks to pipelines many entrepreneurs in what came to be called Petrolia did very well. One was Franklin Tarbell, closely connected to the Drake Well, who sold tanks and storage. His daughter, Ida, became a muckraking journalist. She wrote The History of the Standard Oil Company, a 1904 book cited in the Supreme Court’s 1911 antitrust ruling that ended Standard’s monopoly.

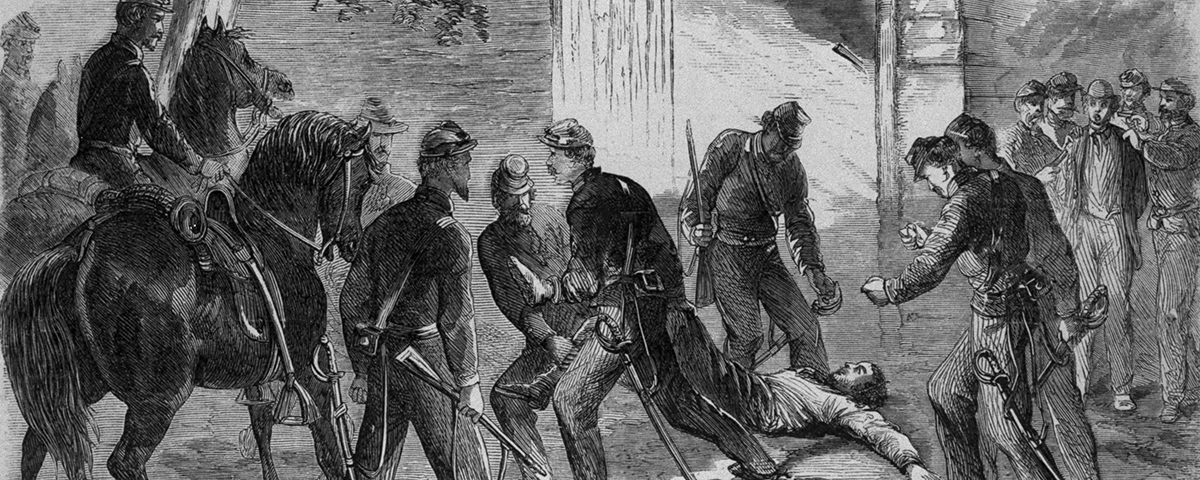

However, Booth quit wildcatting. In the capital he and co-conspirators hatched the plan that ended Abraham Lincoln’s life on April 14, 1865. Two weeks later, pursuers confirmed Booth’s demise by noting the JWB tattoo on his dead wrist. Soldiers buried him in Washington at what is now Fort Lesley J. McNair.

In 1869, his family re-interred the remains, unmarked, in a family plot in Baltimore’s Green Mount Cemetery. For decades, newspapers claimed Booth made a bundle in oil. In truth, Booth the wildcatter lost $6,000—today, nearly $98,000—that Booth the actor, perhaps about to lose his voice and therefore his career, badly needed. In an irony, John Booth gave sister Rosalie a $1,000 stake in the Homestead Well, 17 miles from Franklin. In February 1865, the Homestead came in and for a brief while was outproducing anything in the vicinity, yielding some 28,000 barrels.

The Booths never pursued revenue from the shortlived gusher. “The stock must have been in Rosalie’s hands following the assassination, but it was never sold or transferred, “ Ernest Miller wrote in a 1912 study of Booth’s turn as a wildcatter. “Following the disaster, the Booth family washed their hands of everything and anything John Wilkes had touched.”