After a 10-year reign as heavyweight champion and—at one time—the most popular and most reviled athlete in America, John L. Sullivan had legitimized organized prizefighting, moving it from the outlawed bare-knuckle era to the more ‘humane’ gloved sport.

Blood poured from John L. Sullivan’s nose as he plopped heavily onto his stool in the corner of the ring. It was September 7, 1892. Having reigned for 10 years as the heavyweight champion of the world, and with 45 straight victories under his belt, Sullivan was now feeling every bit his 33 years of age. The stale atmosphere inside the smoky arena, crammed with 10,000 screaming spectators, exacerbated conditions as New Orleans September heat took its toll on fighters and audience, drenching every face and body in a steady sweat. Sullivan’s labored breathing this early meant it would be a long, hard night.

Challenger Jim Corbett had given him all he could handle during the first five rounds. Lighter by some 25 pounds, and eight years younger, Corbett was hard to hit—he kept slipping and dancing just out of reach. Even more troubling was the younger man’s ability to land stinging blows over the champ’s guard. One had broken Sullivan’s nose. The champ’s handlers crowded around, working feverishly to staunch the flow of blood with gel and gauze. Sullivan knew he was in the fight of his life.

Fortified with drink and caught up in the drama, the crowd roared in nervous excitement. If they were solidly behind the champion at the outset, doubt of the outcome now threatened to sweep the arena. Incredibly, an upset seemed in the offing.

Sullivan looked surprisingly vulnerable—far off his peak form of three years earlier, when he had demolished feisty Jake Kilrain in Richburg, Miss. in 1889, administering a terrific beating in 100-degree-plus heat. In what was the last bare-knuckle heavyweight championship bout in the United States, that contest had lasted a grueling two hours and 16 minutes, through an astonishing 75 rounds.

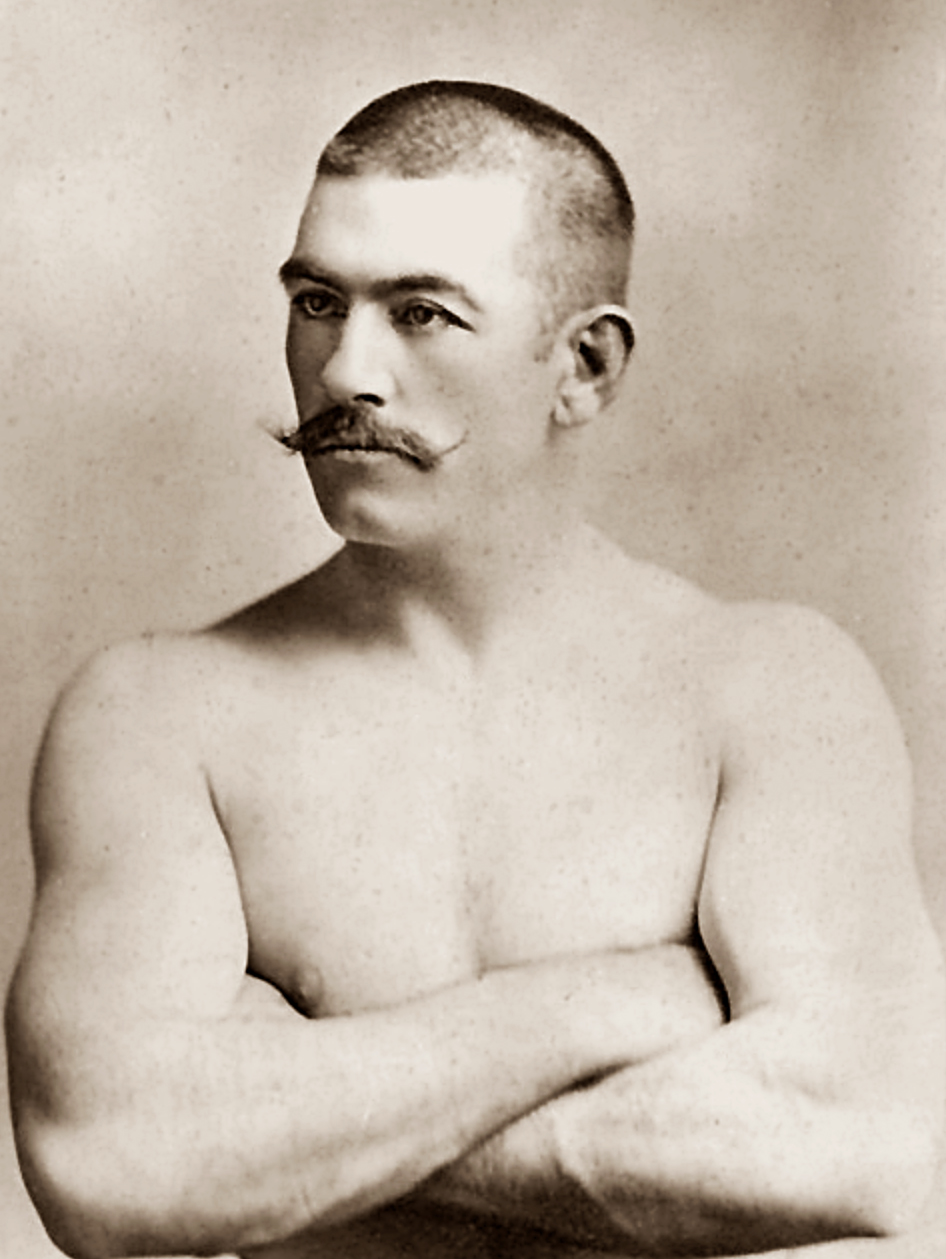

But Sullivan hadn’t fought since. As recently as two months before his contest with Corbett, Sullivan’s weight had hovered above 250 pounds—far too much to carry on his 5-foot-10 frame. Thanks to rigorous training, he had dropped to 212, but he wasn’t nearly as firm as during his last title defense. Corbett, in contrast, had been active. It showed. His physique was impressive. Three inches taller than Sullivan, Corbett was all muscle and sinew.

The bell for round six sent the two fighters to midring. In customary fashion, Sullivan charged like a bull. Corbett ducked a wild right and countered with a hook into Sullivan’s face, then danced out of range. Sullivan shook it off and advanced. “That’s a good one, Jim,” he said. Corbett grinned in response, buoyed by confidence.

Earlier, feigning indifference, he had ignored the champ during referee John Duffy’s prefight instructions. More insulting, instead of touching gloves at the break, Corbett had wheeled on his heels to show Sullivan his back. “Let it go!” he called over his shoulder. That was too much. The champ wasn’t used to such insolence. He’d teach the pup a lesson. So far, however, it wasn’t going well.

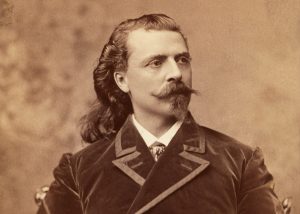

At the close of the 19th century the very name John L. Sullivan conjured up intense emotion across America. Known as the “Great John L.” and the “Boston Strong Boy,” Sullivan was either revered or loathed depending on a person’s feeling toward boxing, an admittedly violent and ugly sport. In any case, Sullivan, largely self-taught on the street, held the public enthralled with his ability to knock opponents senseless. Influencing the people’s reaction to him was his bigger-than-life personality, with a prodigious talent in the ring exceeded by a tremendous capacity to spend money and hoist too many intoxicating drinks. During the course of his professional career, Sullivan earned more than $1 million—an immense sum of money at the time. In later years he admitted that he had squandered most of it on whiskey.

As a struggling newcomer in the late 1870s, Sullivan embodied the American spirit—proud, cocky and tough as nails. He traveled the country looking to build a reputation; characteristically entering a popular saloon in town, he would march up to the bar and loudly proclaim that he could lick any sonofabitch in the place. With fists to back up the boast, especially a thunderous right, his rise was meteoric. Soon Sullivan was flaunting his prowess by offering bets of $500 or $1,000 to any man able to last four rounds in the ring with him, and he didn’t stop climbing until he reached the top, securing the heavyweight crown in 1882. Still, fighting was hard. After the Kilrain bare-knuckle triumph in 1889, he guessed that he was done with the sport.

Sullivan deserved a rest. At 31 he had accomplished more than any man could expect, rising from a working-class Boston Irish upbringing to become the nation’s first sports hero. “I’m getting too old,” he said at the time. Like most fighters, he hated to train, finding it increasingly grueling to drop weight as he got older—self-denial was never among the man’s natural attributes.

Besides, America was changing. It had moved beyond its frontier beginnings and begun to exhibit a more mature, genteel character, something more befitting a civilized society. By the late 1800s, most states, including Mississippi, site of the Kilrain bout, had outlawed bareknuckle fighting, considering it too barbaric. Sullivan and Kilrain had broken the law. With the prize money in hand, the champ had fled to New York just ahead of the authorities, but was later extradited to stand trial. Indicted for prizefighting and assault and battery, he ultimately managed to squelch the charges, but only after having spent more in legal fees than he had earned from the fight. He vowed never to fight under the old prizefighting rules again. Boxing with gloves was legal.

Perhaps an even greater influence on Sullivan’s decision to take a break was a new, safer interest—the theater. Acting would be a far easier way to make a living, keep him in the limelight and allow him to earn enough to maintain his lavish lifestyle.

Not surprisingly, abandoning the ring was easier said than done. Sullivan tried to transfer his ring persona to the stage, playing a blacksmith in the production Honest Hearts and Willing Hands. Of his New York debut one critic wrote: “[Sullivan is] little more than an amateur. He is too apt to miss his punctuation marks, and to neglect to put the emphasis in the proper place.” And theater audiences found his acting a poor substitute for his earlier career as the world’s most feared pugilist. While polite, they saved their greatest applause for the boxing exhibitions the reigning champ conducted after each stage performance. Besieged with constant calls to defend his title, Sullivan felt his popularity waning as he continued to remain idle.

Ironically, an Australian champion—a man Sullivan refused to fight because he was black—indirectly helped draw Sullivan back to the ring. For years Sullivan had denied the Aussie Peter Jackson a bout, preferring to restrict his fights to white opponents. Though he did so not out of fear but from the cultural prejudice of the day, it lessened the champ’s credibility— at least outside his own country. A clever and ambitious young fighter from California, Jim Corbett, held no such misgivings. Moreover, Corbett possessed great potential and the youthful trait of fearlessness. He set his sights on Sullivan, and saw an opportunity to lure the world champ out of retirement through Jackson.

With an in-your-face move, Corbett displayed bold promotional savvy, taking on the Australian champion in San Francisco on May 21, 1891. Though the fight had ended in a “no-contest” after 60 rounds, Corbett gained increased legitimacy and notoriety in boxing circles. Jackson was considered a formidable opponent. The fact that Sullivan had long ducked the black man gave Corbett fuel to bait the absent world champion.

Later that year, on June 26, Corbett had the good fortune to spar with Sullivan at a West Coast benefit. Though not a serious contest—the fighters wore tuxedos—the event gave Corbett firsthand insight into the champ’s fighting style.The knowledge was to come in handy. When Sullivan embarked from the West Coast in July on a theatrical tour of Australia, Corbett ratcheted up the heat by sending the aspiring actor a box of Havana cigars as a parting gift. He arrogantly signed the card: “Bon voyage! James J. Corbett. That California dude!” Sullivan reportedly tossed the package overboard in disgust.

The Australia trip proved disappointing. Native crowds continually taunted Sullivan over his refusal to fight their favorite son, Jackson, and theater critics scoffed at his acting. In November the Strong Boy returned to Boston in a foul mood, irritated with what he considered an ungrateful public and fed up with barbs and challenges from boxing wannabes. He issued a public challenge to “bluffers” to fight him for a purse of $25,000 and a bet of $10,000—winner take all. The letter appeared in newspapers throughout the United States and abroad as an open invitation, but Sullivan listed three particularly irksome prospective challengers by name:

First come. First served. I give preference in this challenge to Frank P. Slavin of Australia, as he and his backers have done the greatest amount of blowing. My second preference is that bombastic sprinter, Charles Mitchell of England, whom I would rather whip than any man in the world. My third preference is James J. Corbett, who has uttered his share of bombast.

Sullivan, stung by the Kilrain experience and likely eager to avoid the greater punishment that came with bare-knuckle fighting, stipulated that the contest would be fought under the Marquess of Queensberry rules. Five-ounce gloves were to be used instead of bare knuckles, and rounds were to be a standard three minutes. Under the old London Prizefighting Rules, instituted in 1838, bare-knuckle rounds were of unspecified length, ending only when one of the contestants touched ground with a knee. Each fighter then had to “come to scratch” within one minute—meet at a line drawn in the dirt by the referee. Sullivan wanted a fight, not a foot race.

Corbett’s gambit had worked. Upon seeing the invitation of challenge, Corbett immediately entrained to New York to raise the $10,000 ante. Sullivan dismissed the threat. “He wants to fight me, eh?” he scoffed. “Well, all the training I need is a hair cut and a shave to beat his head off in one round.”

Most gamblers shared that confidence—after all, the Great John L. was invincible. After the contract was signed on March 10, 1892, early betting heavily favored the reigning champ 4-to- 1, despite concern over his lack of conditioning. In an exhibition in Brooklyn just days before the fight, The New York Times noted the layer of fat on the champ’s belly and a shortness of breath after six minutes of easy sparring.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper was particularly critical of the champion in an article that ran the week of the fight. The author, Philip Poindexter, was no fan of boxing, calling it a “carnival of brutality.” Of Sullivan he wrote: “The truth is that he is as ignorant a man as ever broke rock for a living, or thrashed his wife for diversion. He is a bully and a blackguard.” And even though his training regimen had eliminated much of Sullivan’s extra weight, Poindexter noted the athlete’s paunch. “He is still fat, to my thinking—objectionably fat for the work he has before him. From the waist down he is in no sense a fine man.” Still, the author felt the outcome certain. “It seems to me incredible,” Poindexter wrote, “that Corbett will be able to withstand the wonderful blows of the present champion.” Photographs of the two combatants training seemed to bolster that prediction—the champion depicted seminude to showcase his upper body, and the challenger shown sparring in tie and suspenders.

The fight was held in New Orleans amid a carnival atmosphere. Prefight publicity was extravagant, helped immensely by the contrasting styles of the combatants—Sullivan the picture of an undisciplined barroom brawler, and Corbett the college boy who practiced the science of boxing. Most enticing, after a three-year hiatus, the boxing public would again get to see the legendary John L. in action. Anticipation was so great that the contest drove the upcoming presidential election, Lizzie Borden and the “Big Easy’s” cholera outbreak off the front page of many newspapers.

Fight fans arrived by special train from across the nation. “The most intense excitement prevailed throughout the city,” reported the New Orleans Times Democrat. “The streets were thronged with visitors of all classes, from the millionaire to the baker to the fakir. Politicians, lawyers, merchants and gamblers elbowed each other in all public places on comparatively equal terms.” Tickets went from $15 to $20. The city’s new boxing venue, the impressive Olympic Club, hosted the event. Noted as one of the finest arenas of its kind in the world, the stage was set for a momentous battle.

Part of Corbett’s strategy was to irritate the champ and distract Sullivan from the task at hand. Before the fight, Corbett contested everything: who would enter the ring first, who got which corner, even the champ’s stomach wrap. While Sullivan grew angrier, Corbett smiled and waved to the crowd. “I was trying to convince him that he was the last person or thing in the world I was thinking about, ” Corbett later admitted in his autobiography. In a fight with a man as dangerous as Sullivan, any advantage would help.

As the fight wore on, Corbett continued to bob and weave, eluding Sullivan’s big swings. The defensive tactics frustrated the champ, who continued to chase the younger man haplessly about the ring. Losing composure, Sullivan at one point stood at center ring. “Come on and fight!” he hollered. Corbett, too smart to be baited, followed his handlers’ instructions and kept his distance, waiting for the more experienced man to tire.

The crowd grew anxious, wanting some toe-to-toe action. By the eighth round, Corbett had become the aggressor, forcing Sullivan time and again against the ropes. Sullivan, his face and chest now bathed in blood, looked tired as the bell sent the two fighters to their corners at the end of the round. It was much the same for the rest of the fight. With every punch the champ landed, three or four came whistling back in return. Corbett hammered at the man’s stomach and face, all the while staying clear of his opponent’s treacherous right. In the 19th, the challenger laughed sarcastically. Sullivan was his for the taking.

The end was near. “Sullivan looked tired for the twentieth round,” reported The New York Times, adding:

His left was very short; he was blowing hard and seemed very cautious, but he was the same resolute, ferocious man of yore. Both exchanged rights, and Sullivan was beaten to the ropes with a right and left. The champion was nearly knocked down with the left on the stomach and right to the head. Corbett was dead game and unhurt so far. Sullivan tried a right, and received five clips on the head and stomach. The champion’s knees were shaking, and he seemed unable to defend himself. Sullivan was fought to the ropes with heavy rights and lefts, and the gong seemed his only safety.

By the 21st round, the old champion was battered and spent. It was amazing that it had lasted that long, a testament to Sullivan’s grit. Corbett moved in for the kill. A feint followed by another left hook to the jaw staggered the Great John L. against the ropes. Corbett pounced, throwing uncontested shots with both hands. Sullivan’s reign as champion was seconds from over. After taking a straight right to the jaw he collapsed face down with a thump. He tried to rise. The crowd grew hushed. Somehow the old warrior managed to prop himself up on one elbow. That was it. He’d later say that his muscles were still there, but the machinery was played out. Referee Duffy’s arm swung downward in cadence with his count. Six. Seven. Eight. Before he reached 10, gravity pulled the exhausted Sullivan flat to the floor. There was a new champion. Two minutes later Duffy and Sullivan’s manager were helping the defeated man to his corner.

Corbett later attributed his victory to speed, superior training and psychology. “It is easier to become the champion than to be one,” he said, wise beyond his years. However, the new champion’s mood to celebrate was tempered by the fickleness of the crowd, which he found disgusting. “It made a lasting impression on me,” Corbett later wrote, saddened at how quickly the crowd’s allegiance shifted. “I realized that some day, too, they would turn from me when I should be in Sullivan’s shoes lying there on the floor.” Every champion knows deep down that it’s just a matter of time before he runs into someone with more fire in the belly.

Dejected but magnanimous in defeat, Sullivan seemingly agreed. Having regained his senses after the knockout, the former champion raised an arm to silence the crowd. “Gentlemen,” he said, “it’s an old story. I fought once too often. But I’m glad it was an American that beat me and the championship stays in this country.” The sin of not knowing when to hang up the gloves was to be the bane of many future fighters. Simply put, the great John L.’s overconfidence blinded him to time. Fighting was a young man’s game, and he was not a young man. Afterward, in the privacy of his dressing room, he broke down and cried.

Sullivan supporters were shocked at the news of his defeat. In cities across the nation, fight fans had gathered around poolrooms and saloons, anxiously awaiting round-by-round accounts by wire. The champ’s admirers had little to cheer about. The Ohio State Journal reported one typical reaction:

In Columbus, an old Irishman asked a pedestrian after the fight, “Did John kill him?” “Not a bit of it, John was knocked out,” was the reply. The old man laughed in derision and when assured such was the case said, “Not a damn word of it do I believe. I will wait the mornin’ papers.”

The next day’s edition of the New Orleans Picayune described the action succinctly: “It was the old generation against the new. It was the gladiator against the boxer.” Many newspapers attributed the loss to Sullivan’s “easy living,” a veiled reference to his history of overindulging in drink.

Just 10 days after their championship bout, the two adversaries met again—this time in a benefit for the ex-champ at New York’s Madison Square Garden. Sullivan’s face wore the punishment of defeat, his upper lip swollen to twice its normal size. At least 5,000 fans paid as much as $6 for the privilege of paying homage to their beloved hero. Corbett contributed $1,000, and the two men treated the crowd to a friendly sparring match, this time with gloves as big as feather pillows.

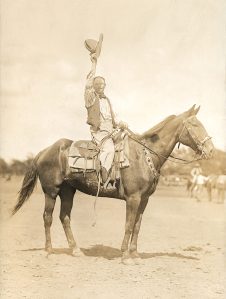

Except for feeble exhibitions to help make ends meet, Sullivan was apparently done with sport. He hung around boxing, being introduced to the crowd at important fights—always to a tremendous ovation—sometimes serving as another fighter’s second or acting as referee, even occasionally covering a bout as a correspondent. He seemed to have accepted the fact that his time was over. Yet in 1905, aged 46, at least 75 pounds over peak fighting condition and 13 years removed from the sport as a competitive fighter, he stepped into a ring one final time for a sanctioned bout. Grossly out of shape, he managed to land a wild haymaker, knocking his 25-year-old opponent out in the second round. It was his last hurrah. Most spectators considered the bout a farce. He lived another 13 years, managed to stay sober and toured the country giving temperance lectures.

Following his death on February 2, 1918, his New York Times obituary called him the world’s “most popular ring gladiator.” Not until Babe Ruth, Red Grange and Bobby Jones dominated the sports scene in the 1920s, did an athlete command the country’s attention as John L. Sullivan. And it was not until Joe Louis captured the heavyweight crown in 1937 that a fighter’s reign lasted longer. For a time, Sullivan was bigger than life. He had transcended sport, a symbol for the entire nation awakening to its status as a world power.

Sullivan is remembered as the man largely responsible for having legitimized organized boxing. He took it from its barbaric infancy, when unsavory men staged bouts in secrecy before “lowclass” spectators, and brought it to a much wider audience. By the time Corbett put Sullivan on the canvas, boxing had become an accepted sport, with contests conducted before both men and women, enjoyed by society’s leading citizens.

The New York Times ran an anecdote that captured Sullivan’s character. He was driving a sleigh when the harness broke and the horse bolted. Sullivan hung tight to the reins and was bounced over the rutted roadway until he lost his grip and landed hard in a snow bank. A spectator ran up and asked why he hadn’t let go sooner. “Oh, go to hell,” the fighter yelled. “I never let go.”

As for Jim Corbett, he never achieved the adulation enjoyed by the man he beat. By 1905 he was already out of boxing, having lost his title to Bob Fitzsimmons in 1897. Though he failed to match his predecessor’s longevity as champion, experts considered Corbett a revolutionary in the sport—a champion who possessed perhaps the fastest fists in history. He moved boxing from an era where brute strength ruled the day to one where finesse and science mattered. He served as pallbearer at Sullivan’s funeral in 1918 and died himself in 1933.

Originally published in the February 2006 issue of American History. To subscribe, click here.