Slavery was the foundation of the antebellum South. More than any other characteristic, it defined Southern social, political, and cultural life. It also unified the South as a section distinct from the rest of the nation.

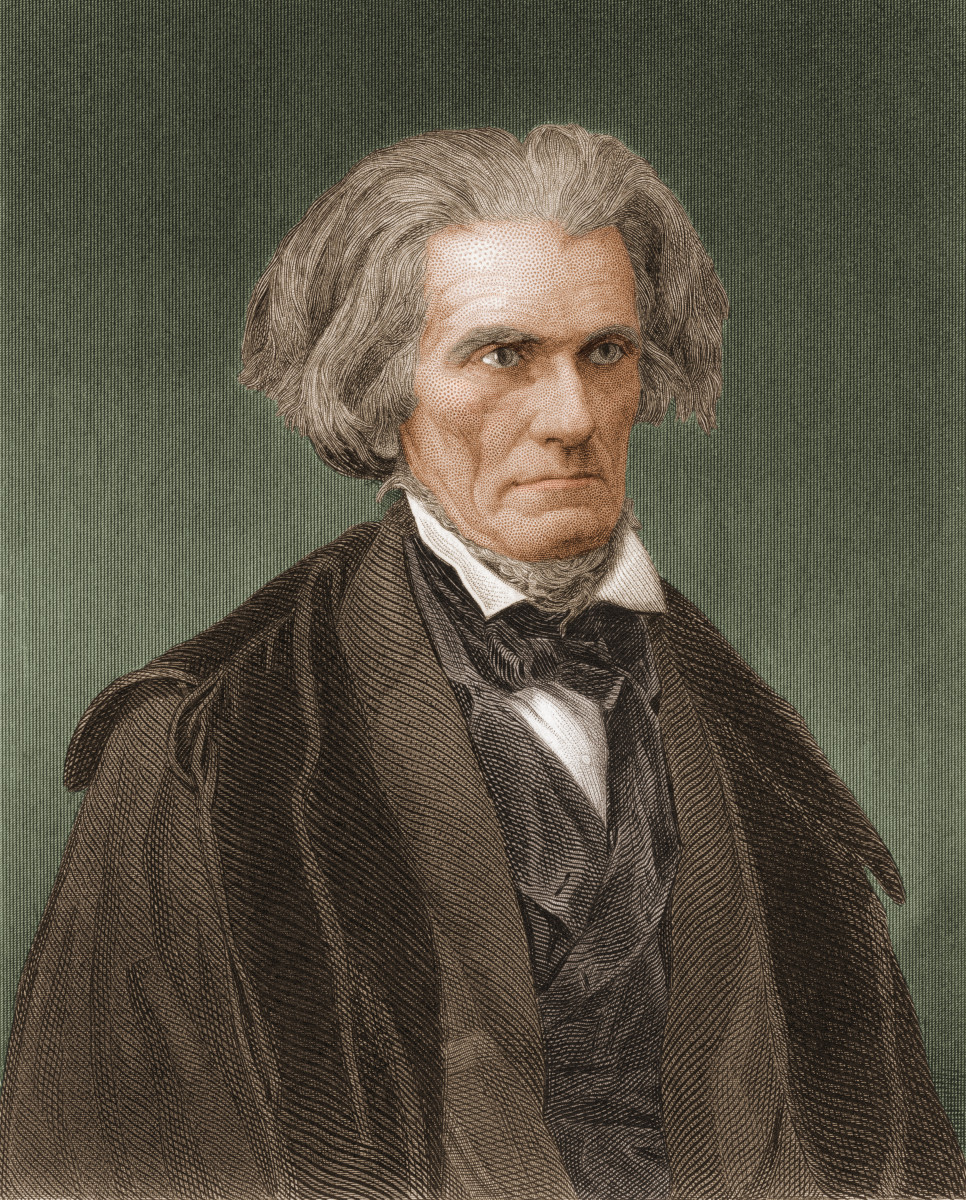

John C. Calhoun, the South’s recognized intellectual and political leader from the 1820s until his death in 1850, devoted much of his remarkable intellectual energy to defending slavery. He developed a two-point defense. One was a political theory that the rights of a minority section—in particular, the South—needed special protecting in the federal union. The second was an argument that presented slavery as an institution that benefited all involved.

Calhoun’s commitment to those two points and his efforts to develop them to the fullest would assign him a unique role in American history as the moral, political, and spiritual voice of Southern separatism. Despite the fact that he never wanted the South to break away from the United States as it would a decade after his death, his words and life’s work made him the father of secession. In a very real way, he started the American Civil War.

Born in 1782 in upcountry South Carolina, Calhoun grew up during the boom in the area’s cotton economy. The son of a successful farmer who served in public office, Calhoun went to New Haven, Connecticut, in 1801 to attend Yale College. After graduating, he attended the Litchfield Law School, also in Connecticut, and studied under Tapping Reeve, an outspoken supporter of a strong federal government. Seven years after Calhoun’s initial departure from South Carolina, he returned home, where he soon inherited his father’s substantial land and slave holdings and won election to the U.S. Congress in 1810.

Ironically, when Calhoun, the future champion of states’ rights and secession, arrived in Washington, he was an ardent federalist like his former law professor. He aligned himself with the federalist faction of the Republican party led by Speaker of the House Henry Clay of Kentucky. He also became a prominent member of the party’s War Hawk faction, which pushed President James Madison‘s administration to fight the War of 1812, the nation’s second war with Great Britain. When the fighting ended in 1815, Calhoun championed a protective national tariff on imports, a measure he hoped would foster both Southern and Northern industrial development. After the War of 1812, Congress began to consider improving the young republic’s infrastructure. Calhoun enthusiastically supported plans to spend federal money, urging Congress to “bind the Republic together with a perfect system of roads and canals… Let us conquer space… We are under the most imperious obligation to counteract every tendency to disunion.”

Calhoun left the legislature in 1817 to become President James Monroe‘s secretary of war and dedicated himself to strengthening the nation’s military. He succeeded, spurring revitalization of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point under the leadership of Superintendent Sylvanus Thayer and improving the army’s administrative structure with reforms that endured into the 20th century. ‘If ever there was perfection carried into any branch of the public service,” one federal official wrote, “it was that which Mr. Calhoun carried into the War Department.”

Calhoun’s success in improving the country’s war-making capabilities came at the price of a stronger, less frugal federal government. Not everyone was pleased. “His schemes are too grand and magnificent…,” a detractor in Congress wrote. “If we had a revenue of a hundred million, he would be at no loss how to spend it.”

Calhoun hoped to use his accomplishments as war secretary as a springboard to the presidency. When that dream fell through, however, Calhoun had no problem accepting the vice presidency under staunch federalist John Quincy Adams in 1824. Adams was glad to have Calhoun in his administration, having held him in high esteem since their days together in Monroe’s cabinet. Adams was particularly impressed by Calhoun’s “ardent patriotism,” believing Calhoun was “above all sectional and factious prejudices more than any other statesman of the Union with whom I have ever acted.” This was an image Calhoun cultivated during the 1824 election campaign.

It turned out that Calhoun was late in publicly promoting his commitment to federalism. By this time, Southerners were increasingly taking an anti-federal-government stance. In the North, industry and the economy it created grew in influence and power every day. Meanwhile, the rapidly expanding cultivation of cotton and other cash crops was committing the South to an agrarian economy and culture, which depended on slavery. The country was dividing into two increasingly self-conscious sections with different priorities. And as the issue of slavery came to the fore in American politics, the South found itself on the defensive. Because of the South’s investment in large-scale agriculture, any attack on slavery was an attack on the Southern economy itself.

The issue came to a head in 1819 with the debate over whether to allow the Missouri Territory to become a state. The result was the historic Missouri Compromise of 1820, which permitted the territory to enter the Union as a slave state while Maine entered as a free state, maintaining the balance between free and slave states at 12 each. The compromise also prohibited slavery in the remainder of the Louisiana Purchase north of Missouri’s southern border.

On the surface, the Missouri Compromise seemed to heal the sectional breach that slavery had created. But the fact that the debate had divided along sectional lines awakened the South to the reality that it was a distinct section—a section that was apparently inevitably destined to be a minority in the Union, while the Northern states enjoyed increasing political representation and power born of rapid population growth.

In the 1820s, Southerners grew increasingly anxious about the North controlling the federal government and about how that situation threatened the South and its distinctive institutions. They looked to leaders who would limit federal power. Calhoun unexpectedly found himself the target of sharp criticism from leading South Carolina figures, including Thomas Cooper, the president of the state college. In 1824, Cooper published a widely circulated pamphlet attacking Calhoun. “He spends the money of the South to buy up influence in the North,” Cooper grumbled.

If Calhoun wanted to maintain his status as a Southern leader and reach his political goals, he could not ignore the changing political landscape. He recognized it would be a mistake to maintain his association with Adams, whose ideas to expand the use of federal power to promote national economic, intellectual, and cultural development drew a cold reception in South Carolina. So when Andrew Jackson began preparing to challenge Adams in the 1828 presidential election, Calhoun switched sides. The Democrats rewarded Calhoun by making him their candidate for vice president, and the ticket won.

That same year, Congress passed a highly protective tariff that Southerners bitterly opposed, viewing the measure as sacrificing Southern agrarian interests to benefit Northern industry. The protest against the so-called Tariff of Abominations grew particularly strong in South Carolina, and in response to a request from the state legislature, Calhoun secretly wrote an essay titled “South Carolina Exposition and Protest.” In it, he asserted that states had a constitutional right to nullify any federal government actions they considered unconstitutional. Calhoun had become the chosen mouthpiece for Southern rights. Confirmation of his new status came when Congress adopted another high tariff in 1832 and South Carolina legislators used the principles Calhoun had voiced in his “Exposition and Protest” to declare the tariff “null and void.”

To no one’s surprise, Jackson refused to accept South Carolina’s defiant stance, and the Nullification Crisis of 1832 was born. By now, relations between Jackson and Calhoun were crumbling fast. Problems had been brewing well beforehand, but now, personal conflicts and Jackson’s commitment to the supremacy of the national government made it impossible for the two men to work together. When it became clear that Calhoun’s chief cabinet rival, Martin Van Buren, was Jackson’s choice to succeed him as president, Calhoun quit the administration.

Back in South Carolina, the state legislature chose Calhoun to fill the U.S. Senate seat recently vacated by Robert Y. Hayne. Now, Calhoun had a new and even more influential bully pulpit for his pro-Southern arguments. As a senator, he openly led the fight against the tariff, which he viewed as a zealous attempt by Congress to dictate economic policy. This, Calhoun protested—in repudiation of his earlier views—was an overextension of federal power.

Jackson was no fan of the high tariff, either. But he was furious with Calhoun and considered his behavior treasonous. He loudly threatened to march down to South Carolina and personally hang Calhoun and his fellow nullifiers.

Congress responded to the nullification by drafting the Force Bill, which authorized the president to use military power to compel South Carolina to comply with the tariff. The bill became the target of Calhoun’s first speech upon returning to the Senate. He expressed outrage at the thought of “this government, the creature of the States, making war against the power to which it owes its existence.”

A major crisis seemed imminent until Senator Henry Clay fashioned the Compromise Tariff of 1833. The act gradually lowered the offending tariff, but it confirmed Congress’s authority to enact such protective tariffs. South Carolina responded by repealing its nullification of the tariff, but in a final act of defiance, it nullified the Force Bill.

For Calhoun the tariff controversy had two important results. The first was his emergence as the leading political and intellectual defender of the South. The second was his development of a political philosophy to limit the federal government’s power and thus protect the minority agrarian South and its institution of slavery.

Though it was the tariff controversy that brought Calhoun to the forefront as the leading spokesman for Southern interests, slavery was the most important issue to the South. “I consider the tariff act as the occasion rather than the real cause of the present unhappy state of things,” he confided to an associate early in the Nullification Crisis. “The truth can no longer be disguised, that the peculiar domestick institution of the Southern States and the consequent direction which that and her soil and climate have given her industry, has placed them…in opposite relation to the majority of the Union….”

There were some pockets in the South that supported a high tariff, but all the slave states were unified on the slavery issue. So it made political sense for Calhoun to devote himself to the cause of slavery. From 1833 to 1850— as a member of the U.S. Senate, a private citizen, and during a stint as President John Tyler’s secretary of state in 1844-1845— he worked to insulate the institution from any sort of attack, ranging from abolitionist rhetoric to perceived overextensions of federal power. At stake for him was nothing less than the survival of the South. “I have ever had but one opinion on the subject,” Calhoun wrote. “Our fate as a people is bound up in the question.”

Calhoun’s political thinking had taken a complete turnabout from the federalism of his early years. Now, his goal was to ensure the power of the local agrarian elite by limiting the power of the federal government. “My aim is fixed,” he proclaimed. “It is no less than to turn back the Government to where it commenced its operations in 1789…on the State Rights Republican tack.” He felt that keeping governmental power as decentralized as possible would allow the planters to maintain power and protect the labor system that made their great wealth and status possible. To do this, Calhoun developed two major ideas that are perhaps his greatest legacy: the concepts of state interposition and concurrent majority.

State interposition was first presented in the 1798 Virginia and Kentucky resolutions, written by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison to protest the anti-Republican Alien and Sedition Acts. In these documents, Jefferson and Madison applied the social contract theory formulated by 17-century English philosophers Thomas Hobbes and John Locke to the U.S. Constitution. They argued that because representatives of the states had written the Constitution, the power of constitutional interpretation rested with the states. So if a state believed the federal government was violating the terms of the national charter, it had the right to interpose itself between its people and the federal government to provide protection from tyranny. The Fort Hill Address of July 1831 was the first time Calhoun openly and unambiguously identified himself with the nullification cause. In that speech, he proclaimed that the right of state interposition was “the fundamental principle of our system” and that the federal government must accept that right in order to keep the Constitution and the Union secure. “The Constitution of the United States is, in fact, a compact, to which each State is a party,” he argued. Since, in his view, “the States…formed the compact, acting as Sovereign and independent communities…, the several States, or parties, have a right to judge of its infractions.”

By embracing state interposition, Calhoun dismissed the 1803 Supreme Court ruling in Marbury v. Madison, a ruling that claimed the power of constitutional interpretation exclusively for the judicial branch. He also contradicted his own earlier distaste for those who dabbled in constitutional interpretation. “The Constitution…was not intended as a thesis for the logician to exercise his ingenuity on,” he proclaimed in 1817. Now, in defending the South’s unique economy and society, Calhoun was exercising away.

Calhoun’s exercise went beyond mere theorizing. He helped develop a procedure for states to use their power of interposition. He suggested a state should first call a convention to consider any federal action in question. If the convention determined that the action violated its understanding of the Constitution, then it could declare the action null and void, denying the federal government the power to execute the law within that state. The federal government would then have to either amend the Constitution to legitimize its action or repeal the measure. And if the Constitution was amended in a way the state considered unacceptable, the state had the right to leave the Union.

In developing the concept of nullification, Calhoun did not intend to encourage states to secede. He sought only to give them a way to ensure a strict interpretation of the Constitution and lead the nation away from “the dangerous and despotic doctrine of consolidation” and back to “its true confederative character.” This was especially important for the minority South. “The major and dominant party will have no need of these restrictions for their protection,” Calhoun wrote. The minority, however, required “a construction [of the Constitution] which would confine these powers to the narrowest limits.”

The role of nullification in any future debate over slavery was clear: with the ability to define the terms of their membership in the Union, states would be able to deny the federal government any regulatory power over slavery.

Slavery was an essential condition of Calhoun’s second major contribution to American political thought—the concept of the concurrent majority. In a nutshell, requiring concurrent majority would safeguard slavery in a political climate that was increasingly anti-slavery and in which the slaveholding South enjoyed too little representation to defend its interest. From Calhoun’s viewpoint, the purpose of the concurrent majority concept was to prevent the North, with its population majority, from ruling the nation as a tyrant. “To govern by the numerical majority alone is to confuse a part of the people with the whole,” he argued.

To turn the concept of concurrent majority into law, the Constitution needed to be formally amended. The amendment Calhoun envisioned would also include a provision for each region to have a chief executive invested with veto power over any congressional action, and the power to execute any federal law in accordance with the interests of his region.

During the 1830s and 1840s, the growth of the Northern abolition movement and attempts by Northern politicians to push the federal government to act against slavery confirmed for Calhoun that the North intended to exercise its power as a majority to the detriment of Southern interests. He responded to these attacks with the argument that the Constitution gave Congress no regulatory power over slavery. To Northern politicians who dismissed this argument and continued to push antislavery measures through Congress, he warned that the South “cannot remain here in an endless struggle in defense of our character, our property, and institutions.” He said that if abolitionist agitation did not end, “we must become, finally, two peoples… Abolition and the Union cannot co-exist.” Even compromise was not possible, in his opinion.

As the antislavery movement continued to build up steam, Calhoun continually found himself having to defend slavery on moral, ethical, and political grounds. By the 1830s it had already become unsatisfactory for Southern politicians to apologize for slavery and excuse it as a necessary evil; to do so would have been to admit that slavery was morally wrong. So a major shift in the Southern defense of slavery occurred, one that Calhoun had a large role in bringing about.

Calhoun endorsed slavery as “a good—a great good,” based on his belief in the inequality inherent in the human race. Calhoun believed that people were motivated primarily by self-interest and that competition among them was a positive expression of human nature. The results of this competition were displayed for all to see in the social order: those with the greatest talent and ability rose to the top, and the rest fell into place beneath them.

The concepts of liberty and equality, idealized during the Revolutionary period, were potentially destructive to this social order, Calhoun believed. With the stratification of society, those at the top were recognized as authority figures and respected for their proven wisdom and ability. If the revolutionary ideal of equality were taken too far, the authority of the elite would not be accepted. Without this authority, Calhoun argued, society would break down and the liberty of all men would be threatened. In his manifesto A Disquisition on Government, he asserted that liberty was not a universal right but should be “reserved for the intelligent, the patriotic, the virtuous and deserving.”

Calhoun believed the liberty Southerners enjoyed depended on slavery. Contrary to the writings of those who unabashedly celebrated the North’s free labor system, antebellum Southern society, though definitely stratified, was highly fluid. Fortunes could be and were made in a single generation. Agriculture, specifically cotton, was what made that society so mobile. Cotton was a labor-intensive crop, and as a farmer acquired greater cotton wealth, he required a greater number of field hands to work his expanding fields. So the ownership of slaves became a measure of status and upward mobility. To destroy slavery, according to Calhoun, would be to destroy a powerful symbol of what motivated the Southern man to improve himself.

In the end, Calhoun supported the institution of slavery for many reasons, but at the bottom of all his argument was this: he believed the African race was inferior. He shared the prevailing prejudices of the day—held in both the North and South—that black people were mentally, physically, and morally inferior to whites. This inferiority necessitated that they be slaves. “There is no instance of any civilized colored race of any shade being found equal to the establishment and maintenance of free government,” Calhoun argued. He pointed to the impoverished living conditions of Northern free blacks as proof that black people lacked the ability to exercise their freedom positively.

In Calhoun’s view, slavery benefited black people. “Never before has the black race…from the dawn of history to the present day, attained a condition so civilized and so improved, not only physically, but morally and intellectually,” he asserted in Congress. “It came to us in a low, degraded, and savage condition, and in the course of a few generations it has grown up under the fostering care of our institutions.”

Slavery provided black people with a quality of existence Calhoun believed they were incapable of obtaining for themselves. To his mind, despite all the progress the race had supposedly made in America, to free the slaves and place them in situations where they would have to compete with white people on an equal basis would only result in catastrophe. The freed slave’s inherent inferiority would place him at such a disadvantage that he would not be able to achieve the quality of life he enjoyed as a slave, Calhoun insisted.

Calhoun noted that slave-owners provided for their slaves from birth to infirmity. He urged critics of slavery to ‘look at the sick, and the old and infirm slave, on one hand, in the midst of his family and friends, under the kind superintending care of his master and mistress, and compare it with the forlorn and wretched condition of the pauper in the poor house’ in Europe and the North. In support of his argument, he cited census figures indicating that free blacks were much more likely to suffer mental or physical disabilities than were slaves.

In the long run, Calhoun believed, regardless of what happened with slavery, the progress of civilization would in time doom the inferior African race to extinction. Until that time, he asserted, slavery at least gave black people security and made them useful.

When confronted with the argument that slavery was an exploitative labor system, Calhoun replied that in every civilization a propertied class emerged and exploited the labor of the others. This enabled the master class to pursue intellectual and cultural endeavors that advanced the progress of civilization. “Slavery is indispensable to a republican government,” he proclaimed.

In the South it was inevitable, Calhoun argued, that the African race would be the exploited class. The South merely institutionalized this into a system that benefited both master and servant. The master got his labor and the slave received a standard of living far above what he could achieve on his own.

While Calhoun was defending slavery, he extended his argument to indict the North and industrial capitalism. He asserted that the slave system was actually superior to the “wage slavery” of the North. He believed that slavery, by intertwining the economic interests of master and slave, eliminated the unavoidable conflict that existed between labor and capital under the wage system. The amount of money a master invested in his slaves made it economically unfeasible to mistreat them or ignore their working and living conditions. In the North, the free laborer was as much a slave to his employer as was the black man in the South, Calhoun argued, but he lacked the protection the black slave enjoyed from a paternalistic master.

With or without Calhoun, the Southern institution of slavery would have disappeared, but it will always remain a black mark on the history of the United States and on Calhoun’s reputation. Still, Calhoun deserves a prominent place in the history of American political thought—if only for this irony: while he fought to protect the Southern minority’s rights and interests from the Northern majority, he felt free to subordinate the rights of the African American minority to the interests of the South’s white majority.

After Calhoun’s death on March 31, 1850, one of his greatest foes, U.S. Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, sternly rebuked an associate who suggested that he honor Calhoun with a eulogy in Congress. “He is not dead, sir — he is not dead,” remarked Benton, a staunch Unionist. “There may be no vitality in his body, but there is in his doctrines.” A decade later, a bloody civil war would prove Benton was right.

This article was written by Ethan S. Rafuse and originally published in the October 2002 issue of Civil War Times Magazine.

For more great articles, be sure to subscribe to Civil War Times magazine today!