On October 18, 1859, John Brown lay bleeding on the floor of an armory office in Harpers Ferry, his combat career at an ignominious end. Just 36 hours earlier, he had launched “the great work of my life”—a bold strike to seize the huge federal armory at Harpers Ferry and wage a campaign of slave liberation across the South.

Instead, Brown’s crusade ended just a few yards inside Virginia, when U.S. Marines stormed his redoubt in the armory engine-house. Most of Brown’s guerrilla fighters were left dead or dying, including two of his sons. The few slaves freed in the brief uprising were returned to bondage. And their liberator had been beaten to the engine-house floor by a Marine wielding a light dress sword.

But it was in this moment of abject defeat that Brown began his ascent in to legend. Under hostile interrogation, the wounded prisoner spoke with such eloquent defiance that even his inquisitors expressed stunned admiration. “He is a fanatic, but firm, and truthful, and intelligent,” Virginia Governor Henry Wise told a reporter. “He is a bundle of the best nerves I ever saw cut and thrust and bleeding and in bonds.”

Brown had a similar effect on the Virginians who watched him hang six weeks later, in a stubble field eight miles from Harpers Ferry. Striding briskly up the scaffold steps, Brown positioned himself beneath the noose, shook hands with his hangmen and calmly requested, “Do not detain me any longer than is absolutely necessary.” This last request wasn’t granted; the vast force guarding the gallows needed time to march into place. For an excruciating 15 minutes, the noosed and hooded Brown stood absolutely still atop a trapdoor, awaiting the plunge to his death.

“He behaved with unflinching firmness,” wrote Major Thomas Jackson, soon to be nicknamed Stonewall for his own courage under fire. Near him stood Edmund Ruffin, a proslavery fire-eater who regarded Brown as a “robber and murderer and villain of unmitigated turpitude.” But after witnessing the abolitionist’s bravery on the gallows, Ruffin confided to his diary: “He seems to me to have had few equals.”

Brown has been moldering in his grave for more than a century and a half, but still he stirs complex passions, like those expressed by Wise, Jackson, Ruffin and others who loathed his cause yet praised his courage. Even Brown’s allies weren’t sure what to make of him. William Phillips, an abolitionist correspondent for the New York Tribune, extolled Brown’s war on slavery while describing him as “a strange, resolute, repulsive, iron-willed inexorable old man,” possessing “a fiery nature and a cold temper, and a cool head—a volcano beneath a covering of snow.”

Brown’s extraordinary and enigmatic character is one reason his memory endures. But his power to rivet and perplex Americans goes deeper. Brown’s story touches many of the hottest buttons in our history and culture: race, religious fundamentalism, terror and the right of individuals to oppose their government. He also defies easy judgments. Generations of biographers and mythmakers have tried to fit Brown into ready-made molds: hero or villain, martyr or monster, prophet or madman. Others have labeled him anomalous and irrelevant—“a wild and absurd freak,” as the New York Times put it in 1859. But the man and his mission can’t be so easily dismissed. As the novelist Truman Nelson observed a century after Harpers Ferry, “John Brown is the stone in the historians’ shoe,” too troubling and significant to ever be put comfortably to rest.

The Story Behind John Brown

UNUSUALLY, for such a controversial subject, debate over Brown has relatively little to do with the facts surrounding his well-documented career. Born in 1800 in Connecticut and raised in modest circumstances on the Ohio frontier, Brown was a man of ferocious ambition and faith who endured Job-like tribulations most of his life. He showed talent as a tanner and stock-raiser, but land speculation and dreadful money management drove him into bankruptcy. He recovered to become a leading wool merchant—only to overreach again and end up mired in lawsuits and debt. “For 55 of his 59 years, John Brown was a man on the make who never made it,” observed historians Richard Warch and Jonathan Fanton, who edited a collection of writings about the abolitionist.

Brown also suffered repeated family tragedies. Both his mother and first wife died in childbirth, and he buried eight of his 20 offspring as infants or youngsters. His first wife and several of his children exhibited signs of mental illness, which many Americans would later suspect afflicted him as well.

Yet Brown overcame his trials to emerge, at the improbable age of 56, as a renowned antislavery warrior. Unlike most abolitionists, he was willing to take up arms, which he did first in the Kansas Border Wars, where his exploits included the slaughter of five proslavery settlers. He also liberated Missouri slaves at gunpoint and escorted them to freedom in Canada. Brown then gathered a small secret army for his attack on Harpers Ferry, hoping to free and arm slaves and establish a “provisional government” in the mountains of Virginia. In the chaotic fight that followed, the first person killed was a free black railroad worker, shot in the back by one of Brown’s men. Only a handful of slaves were freed, and it took Marines commanded by Robert E. Lee just five minutes to vanquish the insurrection and capture its leader.

This brief, bloody debacle and the discovery of Brown’s grandiose plans — including a “constitution” creating a revolutionary state with himself as commander in chief —led many Americans to dismiss him as insane. “As mad as a March hare,” opined the Chicago Press and Tribune. Others branded him a deluded messiah who saw himself as “God’s instrument” for the destruction of slavery.

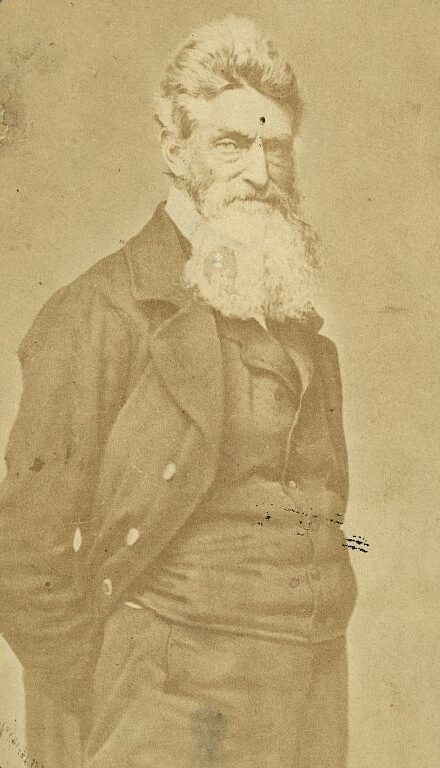

In the century and a half since, many historians have echoed these sentiments, in essence lumping Brown with disturbed individuals who acted out their private demons on a public stage. The two most iconic images of Brown have served to deepen this impression. One, a photograph taken in 1859, shows him with the flowing white beard and glinting eyes of a self-appointed prophet. The other, a 1930s mural by John Steuart Curry, depicts Brown in apocalyptic fury, arms outstretched before a tornado, a Bible in one hand and a rifle in the other. The Union and Rebel troops huddled beneath him recall the abolitionist’s chilling death note: “I John Brown am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away, but with Blood.”

Much of this, however, is caricature. Brown was a clean shaven, well-groomed entrepreneur most of his life, favoring starched white shirts and leather cravats; he only grew a beard to disguise his identity 18 months before Harpers Ferry. And his famous gallows “prophecy” went unheard at the time. Handed to a jail guard, Brown’s final words didn’t become widely known until the 1870s.

More important, the focus on his mental state deflects attention from his many allies, who are generally forgotten in the memory of “John Brown’s Raid”—a phrase that wasn’t used in 1859 and that makes Harpers Ferry sound like a minor, almost personal affair. Far from being a lone gunman, Brown was joined in Kansas and Virginia by a cross-section of society: farmers, artisans, lawyers, poets, Jewish shopkeepers, former slaves, free blacks. Almost none of them hewed to Brown’s fervent Calvinism, and many bristled at his leadership and plans. What they shared was Brown’s militant commitment to destroying an institution they felt violated the nation’s founding promise of liberty and equality for all.

“There was no milk and water sentimentality—no offensive contempt for the negro, while working in his cause,” wrote Osborne Anderson, a black printer in Brown’s band. “Men from widely different parts of the continent met and united in one company, wherein no hateful prejudice dared intrude its ugly self.”

Aaron Stevens, an army bugler and Mexican War veteran, wrote his brother soon after joining Brown: “The grate battle is begun,” adding, “you will alwase find me on the side of human freedom.” John Copeland, a free black educated at Oberlin College in Ohio, cited both George Washington and Crispus Attucks in his letters, noting that it was not “white men alone who fought for the freedom of this country.” William Leeman, a poor shoemaker from Maine, felt guilty about abandoning his parents and sisters but knew they’d approve of his fighting “in a good cause,” even if it cost him his life.

It did, Leeman, just 20, was shot in the face at Harpers Ferry, one of 10 raiders killed in action. Most of the rest were captured and hanged. Of the 18 men Brown led into the town, only Osborne Anderson survived. But judging from their writings—including passionate love letters—Brown’s foot soldiers weren’t suicidal zealots who blindly followed a cult leader to certain death. They were idealistic young men, willing to leave farms and families behind to fight for a cause they cherished—not unlike thousands of men who took up arms in the nationwide conflict that soon followed.

Brown’s many supporters also didn’t fit the mold of wild eyed fanatics. His core financial backers, a group known as the Secret Six, were elite businessmen, ministers and reformers, four of them Harvard graduates. Brown also drew covert support from Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman and other black abolitionists. And while many in the North condemned Brown’s resort to violence, they were galvanized by his courage and eloquence after the raid, particularly his courtroom speech upon receiving a sentence of death.

“I believe that to have interfered as I have done, as I have always freely admitted I have done, in behalf of His despised poor, was no wrong but right,” Brown declared. “Now, if it is deemed necessary that I should forfeit my life for the furtherance of the ends of justice, and mingle my blood further with the blood of my children and with the blood of millions in this slave country, whose rights are disregarded by wicked, cruel and unjust enactments, I submit. So let it be done!”

Brown, a failure in battle, triumphed instead through the power of his words and his demeanor in facing death. He “will make the gallows glorious like the cross,” Ralph Waldo Emerson proclaimed five days after Brown’s sentencing. Henry David Thoreau and many other luminaries joined in this canonization. As Virginia Governor Henry Wise drily noted, if Brown was mad, so were the thousands of “like maniacs” in the North who had come to regard him as a hero and martyr.

White Southerners also seemed unhinged by Brown. In the aftermath of Harpers Ferry, they became panicked and paranoid, seeing abolitionist conspiracies everywhere. This resulted in the arrest and occasional lynching of Northern peddlers and others suspected of stirring slave discontent. “I do not exaggerate in designating the state of affairs in the Southern country as a reign of terror,” wrote the British consul in Charleston, S.C. In Congress, Mississippi Sen. Jefferson Davis conjured “a thousand John Browns” invading the South, and darkly warned that if Southern sovereignty and property were no longer secure within the Union, “we will dissever the ties that bind us together, even if it rushes us into a sea of blood.”

This was, of course, what happened. Harpers Ferry, in and of itself, was a quixotic and doomed assault, devised by a man whose military thinking was as clouded as his business judgment. But the attack exposed—and greatly widened—the angry schism between North and South that led to secession and civil war. Brown lit a fuse that caught because the nation stood on the brink of explosive conflict. In this sense, his story raises an issue that goes well beyond his own sanity and beliefs: the readiness of Americans to slaughter each other by the hundreds of thousands in the 1860s.

How John Brown Has Influenced Us Today

IN OUR OWN TIME, haunted by 9/11, Brown’s actions raise another vexing issue. Despite the best efforts of hagiographers, it’s impossible to wipe blood from Brown’s hands or plausibly deny that he used terror as a tactic. At Pottawatomie Creek in Kansas, his band hauled proslavery settlers from their beds and hacked them to death with broadswords, leaving their mutilated corpses exposed. This sent a truly terrifying and effective message: Proslavery Southerners, who to that point had bullied and killed free-state settlers with impunity, must now fear savage reprisal.

The attack on Virginia was also staged for shock value. Harpers Ferry had few slaves to liberate, and Brown didn’t need the weapons in the town’s U.S. armory; in fact, he left its 100,000 guns untouched during the time he controlled them. But by seizing a symbol of American power, and bringing a thousand pikes to put in the hands of freed slaves, he sought to terrorize the South and jolt the country at large into confronting its great evil.

“It seemed to him that something startling was just what the nation needed,” Frederick Douglass wrote of his secret meeting with Brown, a short time before the attack. Brown also told the journalist William Phillips, “We have reached a point where nothing but war can settle the question” of slavery. In this regard, Brown achieved his goal, at the cost of his own life and that of 25 others who died as a result of his raid, including civilians and several slaves. More than 600,000 more Americans would die in the war that erupted 18 months later. Abraham Lincoln, like most in the North, saw the conflict as a struggle to save the Union. But by its end, he was echoing Brown’s words before the gallows. “This mighty scourge of war,” Lincoln said in his second inaugural, was the “woe due” the nation for slavery. Nothing less could purge the nation of its greatest sin.

Was Brown therefore right in using violence and terror to bring on the Civil War, which most Americans came to regard as a just and necessary conflict?

Brown also stirs eternal and uncomfortable questions about conscience and society. “Is it possible that an individual may be right and a government wrong?” Thoreau asked in 1859, while praising Brown. “Are laws to be enforced simply because they are made?” Thoreau’s answer—and Brown’s— was clearly no. But this set a troubling precedent for many other individuals who believed their principles demanded defiance of an unjust government. John Wilkes Booth took inspiration from Brown, as did late-19th century anarchists, Black Panthers and Weathermen in the 1960s, Timothy McVeigh and anti-abortion bombers. One of the latter styled himself an “abortion abolitionist,” and another, upon his death sentence, invoked Brown by declaring himself “willing to mix my blood with the blood of the unborn.”

To paraphrase Thoreau, is it possible for Brown to have been right, but others who cite his example to be wrong?

There is no easy answer to this or any of the prickly questions that Brown and his actions raise. Nor have the tensions he bared in 1859 — over race in particular — been fully resolved in the 152 years since Harpers Ferry. This is what makes Brown not only compelling, but demanding of continued study and debate. Rather than seek simple or satisfying conclusions, Americans should embrace the complexity of Brown’s story and pose challenging questions, as he did to the nation in 1859.

Tony Horwitz is the author of Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid That Sparked the Civil War, published by Henry Holt and Co.