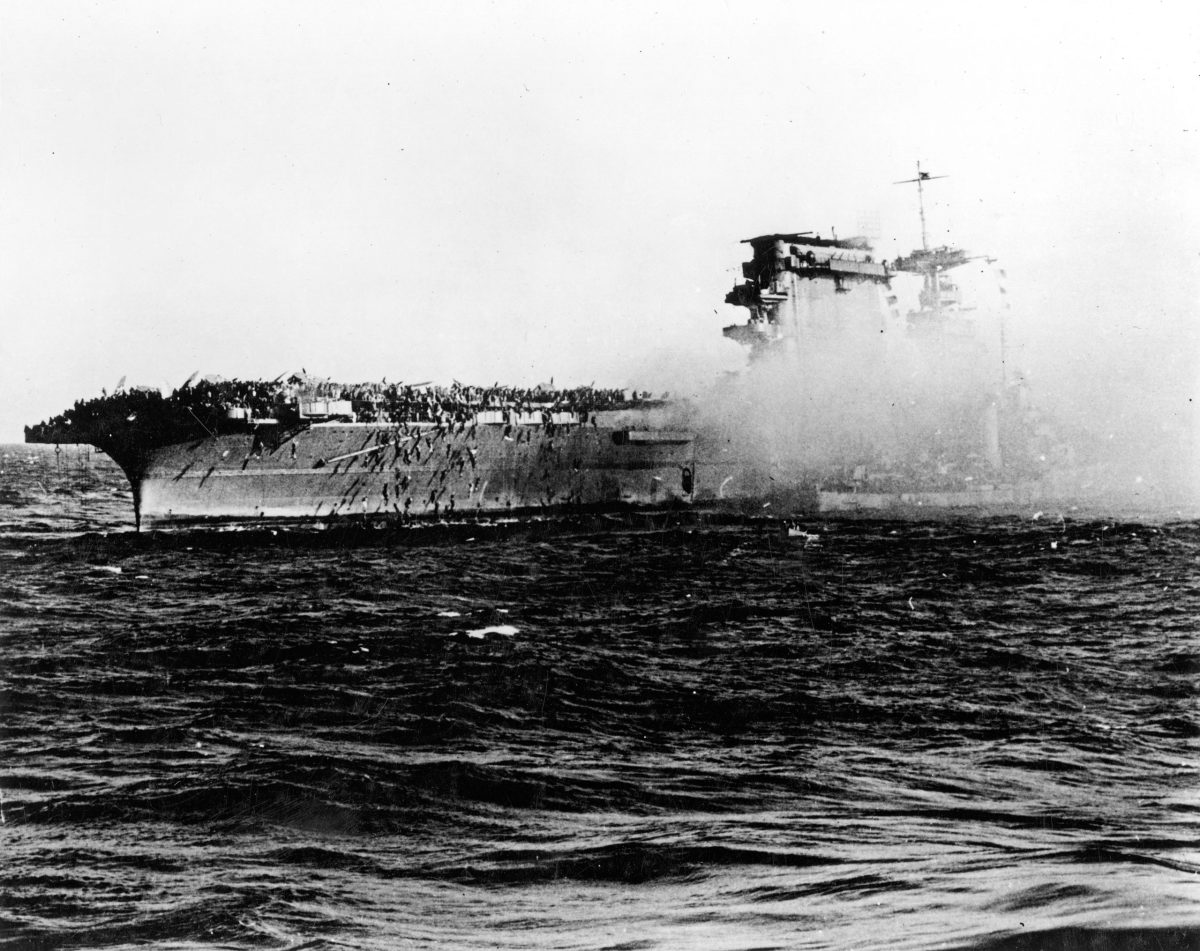

From May 4-8, 1942, American, Australian, and Japanese naval units fought the world’s first engagement decided exclusively by carrier-based air power. Tactically the Japanese could claim a limited success. They sank the carrier Lexington and heavily damaged the carrier Yorktown while losing only the light carrier Shoho. But in strategic terms, the Battle of the Coral Sea was a major Allied victory. For the first time in the Pacific war, the Japanese withdrew without achieving their objective—in this case, vital Port Moresby in Papua New Guinea. And two Japanese carriers, Shokaku and Zuikaku, lost so many aircraft that neither was available to participate in the decisive Battle of Midway four weeks later.

Many “what if” scenarios rely on close calls, in which the outcome pivoted on a single event that went one way but might easily have gone another. In the case of Coral Sea, however, it is almost easier to explain how the Japanese could have won the battle than explain how they managed to lose it. Although both sides committed a number of errors, the Japanese made fundamental, completely avoidable mistakes that gave the Allies an opportunity for victory they really should not have had.

To begin with, Japanese naval planners failed to allocate enough forces to guarantee the job. Confident that the Americans would send only one carrier to dispute the offensive against Port Moresby, the Japanese assigned only two carriers to the main strike force, whereas they easily could have committed a third. As a result, the two sides fought the battle with an almost equal number of carrier aircraft.

Second, the Japanese divided their efforts between two objectives located hundreds of miles apart. In addition to seizing Port Moresby, they also sought to capture the island of Tulagi in the Solomon archipelago for use as a seaplane base. While the Tulagi operation made good sense as a way to keep tabs on naval movements from the American base on New Caledonia, it was of comparatively minor importance.

Moreover, the Japanese operational plan, code-named “MO,” was needlessly complex and depended on the coordination of five major groups: a carrier striking force, a Tulagi invasion group, a Port Moresby invasion group, a support group, and a covering group. Worse, the commander responsible for coordinating these groups, Vice Adm. Shigeyoshi Inouye, remained at Rabaul, hundreds of miles from the prospective battle zone, with no direct feel for the battle’s development.

Finally, the concept of the operation— a pincer movement that would trap the Allied task force between the carrier striking force steaming from the eastern entrance to the Coral Sea and the covering group protecting the Port Moresby thrust at its western end—made sense only on a map. Such a movement depends on having two strong pincers. What passed for the western pincer, however, was so weak that when Allied naval units simply moved in its direction during the battle, the Port Moresby invasion group pulled back. And when it was deprived of air cover with the loss of Shoho, the invasion had to be abandoned altogether. Had the Japanese instead kept their force united, first securing Port Moresby, then turning east to engage the Allied task force, they would not only have achieved their main objective, they would have stood a better chance against American air attacks because more warships would have been on hand to screen the carriers.

Japanese mistakes did not end there. On May 6, the rival carrier groups were only seventy miles apart, but neither spotted the other. In the case of the Americans, their scouting planes turned back just before they would have sighted Shokaku and Zuikaku. But with the Japanese, the striking force commander, Adm. Takeo Takagi, failed to order any scouting efforts at all. On May 7, both groups finally spot ted the other, both launched air strikes, and both air strikes managed to miss their intended targets and attack others instead. It was on this day that the Americans sank Shoho. These mutual errors were far more costly to the Japanese, since the elimination of Shoho badly compromised the Port Moresby operation.

Then, late in the afternoon of May 7, Admiral Takagi took a badly calculated risk and dispatched twenty-seven pilots with night flying experience to locate and attack the main American task force. They indeed located the task force—but they misidentified the American carriers as their own. Of the twenty-seven aircraft dispatched, only six returned.

The following day, both main carrier forces finally found and attacked the other. Yorktown was heavily damaged and Lexington was lost. Shokaku also suffered damage that interfered with flight operations, forcing its returning air group to land on Zuikaku instead. The crew of the overburdened Zuikaku had to push numerous aircraft over its side as soon as they landed. As a result, almost a third of the sixty-nine aircraft the Japanese lost during Operation MO were the direct result of Takagi’s ill-fated air strike on the evening of May 7. And the damage to Shokaku and severe losses to both carrier air groups rendered Shokaku and Zuikaku unavailable for the Midway operation.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Were it not for these fundamental mistakes, MO stood every chance of succeeding in seizing Port Moresby. In that case, the Japanese would have securely anchored their defensive perimeter in the southwest Pacific and established a base for aerial operations against the ports of northeastern Australia. That was where Gen. Douglas MacArthur was marshaling Allied forces for a counteroffensive by way of Papua New Guinea, which the capture of Port Moresby would have vastly complicated, if not precluded altogether. Japan would have had more forces available, therefore, to defend against another counteroffensive from the direction of the Solomon Islands—the Allied landing on Guadalcanal in August 1942, for example.

While it can’t be known for sure whether Shokaku and Zuikaku would have been used at Midway had they been available, it is certainly true that had Operation MO been better planned and managed, it would not have been so costly to the Japanese in terms of aircraft and their crews of well trained airmen. And had both carriers been present at Midway, they might well have provided enough extra striking power to preclude the “incredible victory”—in the words of historian Walter Lord—that abruptly turned the tide of the Pacific war.

Given the disparity in industrial strength between the United States and Japan, it is hard to imagine any scenario by which Japan could have won the Pacific war. But if the Japanese had won the Battle of the Coral Sea, as they might so easily have done, the war would have been protracted by many months, and been rendered vastly more difficult for the Allies.