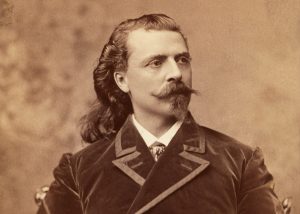

Robert Pinkerton knew a good detective when he saw one, and in his opinion Isaiah Lees was the best of the breed in 19th- century San Francisco.With unprecedented police work, Lees put a lid on crime in one of America’s wildest cities of the time.

If Sherlock Holmes had existed he might have taken lessons from Isaiah Lees, the master detective who broke the mold of the fabled lawmen of the American West. In fact, in one of Lees’ last cases in the mid-1890s, he locked horns with a character named Charley “Scratch” Becker who had learned his trade from Adam Worth. Holmes’ creator, Arthur Conan Doyle, called Worth “the consummate of evil,” and used him as the model for his detective’s nemesis, Professor Moriarty, “a villain of the lowest degree.”

Becker, an accomplished forger with a price on his head in both America and Europe, spent a week “raising” a $12 check to $22,000 and then passed it along to Arthur Dean, a cohort who had established a phony business and a bank account in San Francisco. Dean deposited the inflated check at a bank in nearby Woodland, and cashed a $22,000 draft for gold in San Francisco, then beat it out of town. The loot was divided, and by the time the forgery was discovered several weeks later, the men behind it had vanished. They might never have been tracked down had it not been for detective Lees.

Dean had used several different disguises during his time in San Francisco, but after interviewing everyone who had any contact with him, Lees was able to determine his behavioral patterns and physical appearance. His tedious research produced a description that was sent to the Pinkerton Detective Agency and all the major banks in the country. A bank teller in St. Paul, Minn., used it to identify Dean, and the case began coming together when he and his companion were taken back to San Francisco. Dean was tough, but Captain Lees soon had the whole story. With his information, Pinkerton detectives arrested Scratch Becker and his moneyman, James Creegan, in Paterson, N.J. They had tickets to South America in their pockets.

Instead, they went to the West Coast of North America, where the evidence Lees had gathered made conviction inevitable. Robert Pinkerton, who had already characterized Lees as “the greatest criminal catcher the West ever knew,” wrote him a letter of congratulation on “the conviction of the greatest forger of the age.” He added: “The banks of the world owe you…a debt they can never pay. It is a great victory.” It was just one of a long string of victories in the career of the Captain of Detectives.

The Streets of San Francisco

The California Gold Rush brought all sorts of people to San Francisco, each and every one for the same reason: to get rich, and fast. Some found gold in the Sierras, but more either found digging for it too much like work or searched in the wrong places. For many, the road to riches was stealing, swindling and scheming to relieve the miners of their pokes of gold dust. The pickings were so good that hundreds went west with nothing more on their minds than a life of crime, and before long, no one was safe on San Francisco’s streets.

Among the earliest arrivals was English-born Isaiah Wrigley Lees, who went west from New Jersey in 1849 at age 18. At the time, San Francisco was just a collection of shacks and tents filled with new arrivals like him, and the bay was choked with ships from every corner of the world. Young Lees looked around and smiled. He knew that he was where he wanted to be.

He had gone to work at age 10 in railroad shops, and had even assembled six-guns in Samuel Colt’s Connecticut factory. But gold was the metal at the top of his mind eight years later. He gave up on the idea of panning for it after a time in the mountains and went back to San Francisco to work for two fellow iron workers. Their blacksmith shop turned out tools, stoves, cooking utensils and other things the booming city needed. It was perhaps prophetic that he made locks for the first city jail, and worked with his partners as amateur sleuths to gather evidence against a murderer in their neighborhood.

Lees turned pro in 1853 when he took a job with the newly formed police force. With political thugs in charge of the government, drunken soldiers from the Presidio and sailors from the busy waterfront ruled the streets, and the rookie patrolman saw his share of action. One incident he remembered for the rest of his life was typical, and as he told it:

It happened on Jackson Street, near Dupont when that was a lively part of town. I saw a fellow pick up a cobble[stone] and heave it through the window of Maggie McCormick’s saloon. Then he walked along quietly toward Kearney Street just as if nothing had happened. I slipped after him [and] told him he was under arrest…just as we got opposite a little cul de sac he let drive at me. I ducked and got a blow on the top of my head. If I’d got it on the jaw as he intended, it would have knocked me out.

Well, the little alley was as dark as a tunnel, but I piled into it after my man and ran full against him. I grabbed him [and he drew a gun], but this fellow’s pistol was a short one and he let me have the whole five shots. I felt every one of them sting me and thought he’d made a sieve of my body. But that was no reason why I shouldn’t attend to business, and I did that as soon as possible by getting the empty gun away from him. The hammering I gave that fellow was awful, but he deserved it. I beat his head with the gun, stabbed him with its muzzle ’til I bent the barrel. When I’d worn myself out on him I took him down[town], and he was a sight to behold with the blood on him.

Lees’ next stop was a doctor’s office to see to his gunshot wounds. When he took off his clothes, it became apparent that a silk undershirt had amazingly absorbed the impact of the bullets and left him with nothing more than five angry red welts on his body. He had been lucky, but his days of walking a beat were already numbered. His skills as a detective had become apparent by then.

In those days, the watchman-constable system of policing didn’t involve much more than arresting an offender and tossing him into jail. There was a need for people to investigate crimes, collect evidence and testimony and aid in prosecutions; in short, detectives. The earliest of them were constables called “officers of justice,” and all of them learned their trade on the job. Isaiah Lees mastered it quickly.

He was promoted to assistant captain in 1854, and while he was still expected to walk a beat, his new duties called for keeping his eyes open and his nose to the ground.

The Case of the Chinese Moles

Officer Horace Bell was watching a gambler at the El Dorado Gambling Hall one night when the man held up a diamond stickpin to coax a loan from the dealer. In the twinkling of an eye, a Chinese man grabbed it from his hand and rushed out into the street.

Bell chased him to a Chinese lunchroom and down into its busy basement kitchen. Other officers joined the chase, and an arrest seemed imminent when the thief disappeared through a door across the room. Bell stood guard at the door and ordered the others to keep an eye on the kitchen workers while one of them went to headquarters to bring back his friend Officer Jim McDonald to confront the villain on the other side of that door.

When McDonald arrived, he wasn’t alone. Captain Lees was with him, and, as Bell recalled, “[he] at once took the matter in hand.” He arrested all the Chinese men in the room and had McDonald take them to jail to be searched. Then he opened the door. It led to a storeroom that was empty except for a pile of bulging rice sacks. Had the fugitive given them the slip?

Lees was suspicious of the rice sacks, and asked the steward why there were so many of them and nothing else in the storeroom. As he talked, he cut open one of the bags and found not rice, but dirt.

He had been walking his beat in the neighborhood a few nights earlier when he heard underground noises near the restaurant where the stickpin thief had led them, and he suspected that someone was digging a tunnel from there to the Palmer & Cook bank on the corner. Recalling the earlier night, he said, “I remained and listened until daylight, and have watched the thing ever since…we are now guarding the mouth of their tunnel.”

After more officers arrived, Lees heaved a few of the sacks aside and, as he suspected, they concealed the tunnel’s opening. It was only big enough for a man on his hands and knees, but drawing his pistol and pushing a lantern ahead of him, the detective plunged into the hole. When he reappeared, he was struggling backward, dragging a wounded Chinese man behind him. Lees had been injured by a blow from a crowbar, but had stopped his attacker with a bullet.

There were other “miners” still in the tunnel, and the steward was ordered to go in and bring them out. The men he produced were, according to Bell, “as villainous a looking set of Mongolians as ever crossed the bay to San Quentin.” One of them had the stolen diamond stickpin concealed in his hair.

When Lees and his men searched the place, they found what they said was the finest set of burglary tools any of them had ever seen, and devices used to hollow-out gold coins and ingots, which were then refilled with lead. The altered coins had been circulating for some time, but the tunnel into the bank seemed to have been the gang’s jackpot. Lees put them out of business, though, and the real jackpot was his recognition by the force as a master detective.

Mecca of Greed

Burglars, thieves and killers were not the only source of trouble in the city. Crooked politicians were lined up at the trough of corruption. Many had honed their skills back East, and there was nowhere to go but up, or down as the case might be. It was routine for them to get power by paying thugs to stuff ballot boxes, and, once in power, they voted themselves huge salaries and rewarded their cronies with lucrative building contracts, which were plentiful in a fast-growing city. Few if any of them seemed to notice, or even care about, the needs of a fast-growing population.

Before long, the city ran short of money, and it was plunged into its first recession. Among the stop-gap solutions was issuing a form of virtually worthless money called scrip that was used to pay municipal employees, including the police.

The financial loss was devastating, and the officers didn’t take it lying down. Many of them, Lees included, began a bitter battle with their boss, City Marshal Hampton North, but all it got them was a rebuke from Mayor James Van Ness. In the war of words that followed, Van Ness publicly acknowledged that Isaiah Lees was one of the best men on the force.

Most of the best officers lost their jobs over the protest, and that was a boon for the politicians who gave the jobs to their pals, gathering more power for themselves. When Lees and several other captains were sacked, they refused to budge, noting that they could only be fired for incompetence, which hadn’t even been suggested. When attorney friends volunteered to take up their case, the men were quietly returned to duty. All of them were demoted to patrolmen, though, except Lees, who kept his detective status and soon afterward regained his captaincy.

Among the voices against corruption was that of James King, who gave up a career as a banker to become editor of the San Francisco Evening Bulletin. He turned over a lot of rocks to expose the slime at City Hall, but drew blood when he exposed city supervisor James Casey in May 1856. Unfortunately, the blood was King’s own. The supervisor shot him dead on the street.

The record the outraged politician was defending had been laid out in detail in the paper. Among other things, it was revealed that Casey had elected himself without even being on the candidate slate by replacing the official ballot boxes with false-bottomed ones that were delivered to polling places already filled with votes for him. Cheating at the polls was standard procedure, but what really had Casey upset was that King’s editorial offered proof that the city supervisor had come to San Francisco directly from a cell at New York’s Sing Sing Prison.

The King murder enraged the community, and businessmen responded with a Vigilance Committee that quickly grew to several thousand strong. It included its own constabulary, which effectively replaced the existing police force. The vigilantes drove hundreds of criminals out of town, but their moment of glory was the public hanging of five men, including James Casey. Their reign of terror lasted through the spring and into the summer of 1856, but ended when the regular police force reorganized itself. Among the signs of change was the appointment of 25-year-old Isaiah Lees as first captain of detectives.

Senseless Crime

On Lees’ first day at his new post, Maria Lafourge, a local prostitute, answered a knock at her door and a vial of acid was splashed into her face. Screaming in pain, she ran to a nearby saloon, where the patrons did what they could to help, including sending for the police.

Lees was the officer who responded, and although the girl was hysterical and in pain, he talked quietly with her and learned that she had been quarrelling with a saloonkeeper named Thomas Chieto. Combing the scene of the crime, he found a small bottle wrapped in a handkerchief that had a clear laundry mark on it. Next he searched Chieto’s establishment and found a trunk-full of clothes with the same laundry mark. It was enough for Lees to make an arrest, but he couldn’t pry any information from the man, though he noticed that his trousers were stained and burned. An experiment with fluid from the bottle he had found produced identical damage, but at that point the detective was called away on another case.

When he got back, the suspect had been released and the trunk, which had been taken as evidence, had vanished with him. Furious, Lees went back to Chieto’s saloon for another search. The suspect had changed his trousers, but the detective found the damaged pair stashed under the bar. He noticed that they were wet and concluded that Chieto had tried to remove the evidence of the stains. In his search, he also found a small cork that didn’t fit any bottle behind the bar, but did match the bottle he turned up at the Lafourge apartment. Before his investigation was finished, he sifted through a barrel of rubbish and turned up the original vitriol container. It was all in a night’s work for Lees, but what a night it had been.

In the days that followed, Lees located a battery of witnesses, including the druggist who had sold the acid to Chieto. Key to the trial that followed, of course, was Maria Lafourge herself, who had lost an eye and was terribly disfigured. The saloonkeeper was sentenced to 10 years in prison, but escaped the following year. Most impressive in the trial was Lees himself. In reporting on it, the Evening Bulletin said it was “by far the most remarkable case… ever witnessed,” and added, “Captain Lees has certainly displayed a great deal of ingenuity and has approved himself very good in the detective line.”

The Confederate Navy at Bay

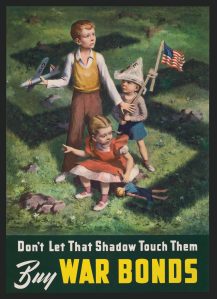

The onset of the Civil War put Captain Lees in a position of defending California from a surprise attack by the Confederates. Southern sympathizers armed the schooner J.M. Chapman in San Francisco, hoping to use it to raid coastal shipping. In early March 1863, word of their scheme leaked out, and when Lees heard about it, he went into action. After locating Chapman in its berth, he put an around-the-clock watch on the ship and carefully watched its captain, who was known to have a fondness for liquor. Lees quickly learned the ship’s sailing date and alerted the captain of the U.S. Navy sloop Cyane to be ready to move at a moment’s notice.

When the moment came, Lees flashed a message to the warship and shoved off in a tugboat with a handpicked crew to join the chase. They were first to intercept Chapman, and Lees was first to scramble onto its deck. The crew had already begun destroying evidence, but the detective gathered up every scrap of paper he could find. Six months later, when the case went to trial, Lees had pieced together the scraps of paper, which turned out to be bills of lading, receipts for arms and other incriminating evidence. Thanks to his dogged, patient work, the conspirators were convicted and Lees himself, whose exploit made national headlines, had another laurel in his crown—war hero.

A Thinking Lawman

Isaiah Lees was first and foremost a thinking lawman. His cases covered every aspect of city life, and not always the underbelly of crime.

When Joseph C. Duncan’s bank failed in 1877, Lees had a hunch that he had brought it on himself, and a quiet investigation turned up evidence of forged stock certificates. The bank’s ruined depositors called for justice, but Duncan had vanished. Lees was convinced that he was still in the city, and roadblocks were set up, but it took more than four months of searching before the detective burst into a room where the banker was hiding. The press and the public had been harassing the police for letting him get away, but once again Lees snatched victory from defeat.

Like other lawmen in the West, Lees had a long record of tracking down bank robbers, but few as dramatic as the capture of Jimmy Hope, perhaps the most wanted thief of them all. Hope had made a name for himself with big hauls back East before he migrated to San Francisco, where he expected to find less law and order. He apparently hadn’t heard of Captain Lees.

When a bank clerk noticed bits of plaster on his desk in the summer of 1881, he didn’t call the janitor, but went to Lees instead. The detective found an upstairs supply closet and ordered it emptied. Next, he lifted some floorboards revealing that layers of brick and strap iron above the vault had been removed, and it was then that Lees went to work.

Stationing detectives in a locked room near the closet, he and a few officers positioned themselves in an alley to begin watching and waiting. They didn’t have to wait long. After nightfall, they saw two men going into the building and flashed a signal to their men upstairs. They captured one of the men, who turned out to be none other than Jimmy Hope. The notorious bank robber served a stretch in San Quentin prison before being sent back to serve more time in New York, where he had managed to elude the police for years.

Lees was rewarded for his years of amazing service when he was made chief of the department in 1897. It was a pyrrhic victory, and he spent his three-year term battling politicians and the jibes of William Randolph Hearst’s San Francisco Examiner, which was pioneering sensational journalism at the time. Lees had avoided the job for years, and having his assessment of it confirmed, he retired and became a private citizen.

When the Greatest Criminal Catcher died in 1902, his funeral was one of the largest the city had ever seen. Even the Examiner joined the outpouring of praise for the man who had found San Francisco a lawless place and left it one of the most orderly anywhere in the American West.

California author William B. Secrest wrote a section on Lees in his 1994 book Lawmen & Desperadoes: A Compendium of Noted, Early California Peace Officers, Badmen and Outlaws. This article was adapted from Secrest’s 2004 book Dark and Tangled Threads of Crime: San Francisco’s Famous Police Detective Isaiah W. Lees (Word Dancer Press, Sanger, Calif.).

Originally published in the October 2006 issue of Wild West. To subscribe, click here.