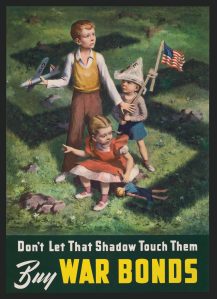

Those of us baby boomers born in the 1940s and 1950s grew up learning a very different brand of American history from the one taught to the generations coming of age during the past four decades. It was a time when radio, movies and the comparatively new phenomenon of television reinforced a positive message: America was a good place to live, its people were outstanding nation-builders, and its ancestors were men and women of vision who spread liberty and democracy across the land. We learned the same story in school, and we could end each day feeling good about our country and ourselves. Not anymore.

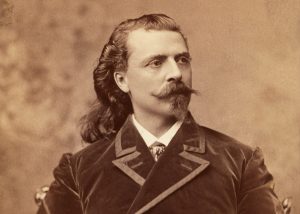

Admittedly, nostalgia is painted in golden hues, but the post–World War II years had a distinctly different tone from what is in evidence today. Some of us may remember Hopalong Cassidy, Roy Rogers and Gene Autry, and the appearance of Walt Disney’s Davy Crockett in 1954-55. They were pictured as genuine frontier heroes, models that children wanted to emulate. In the late 1950s, TV Westerns, often with heroic lawmen, were in vogue and represented more than one-quarter of all network prime time shows. To a later generation, those shows may have been seen as an unrealistic depiction of our past. Yet they showed America as a land of idealism and optimism where right would always triumph.

“Manifest Destiny,” described in pejorative terms today as a smokescreen for greed and conquest, was viewed as a beneficial process whereby Americans could pass the gifts of liberty and democracy to the less privileged, all the while fulfilling their own dreams. The 1962 movie How the West Was Won was the supreme paean to Manifest Destiny. Filmed in panoramic Cinerama by three directors using an all-star cast, backed by a beautiful mix of traditional folk music and original composition, the film told the story of four generations of the

Prescott and Rawlings families as they pursued their destiny across the American continent. Segments titled “The Rivers,” “The Plains,” “The Civil War,” “The Railroads” and “The Outlaws” encapsulated the Western movement. There was tribulation and tragedy, but there was triumph in the end. Progress was seen as inevitable and good. It was an epic tribute to our past and offered hope for the future.

How the West Was Won, however, did not tell the full story. Watching it today, one will immediately notice it is told from the white European standpoint. There are few, if any, scenes from Indian, Hispanic or any other minorities’ point of view. We see white families boating down the Ohio River, fighting river pirates. We see white families emigrating across the Plains. There are wagon trains, Indian fights and buffalo stampedes. The Civil War is encapsulated in the Battle of Shiloh, with a fictional encounter between a Rebel and a Yankee, as the former tries to assassinate Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. There is a great railroad chase, and the outlaws are duly dispatched. Law and order reign supreme. Most of the characters eventually reach California, build homes, start families or otherwise fulfill their destinies. The 19th century is shown as a seminal time of constructing the foundation of a pyramid that others will build upon. How the West Was Won was accurate in its broad overview: Emigrants floated down the Ohio River; they crossed the plains and deserts; there was a great Civil War; Indians and outlaws had to be overcome in “taming” the West. There were no portrayals, however, of any specific historical events. Parker’s Fort, Sutter’s Mill, Whitman Mission, Van Ornum Wagon Train, Grattan Massacre, Sand Creek, Washita and Little Bighorn battles—all are left out. The specifics were fictional while the overall picture was true. The final scene shows a wagon trail evolving into a road, then into a concrete highway, and a small village changing into a great city. America is seen as a dynamic land with even better things in store for the future.

The optimism expressed in How the West Was Won soon came to a grinding halt. The civil rights movement, the death of President John F. Kennedy and the escalating war in Vietnam all contributed to changing the way we looked at ourselves. A darker mood descended. Soldiers, cowboys and frontiersmen were no longer heroes. An anti–military/industrial complex attitude was in the saddle. The standard Westerns of the 1920s to the 1950s were replaced by what were termed “Spaghetti Westerns,” generally filmed overseas, where the good guy was nearly undistinguishable from the bad—and all of them were ugly. Movies emphasized violence on a scale never before seen, and in many instances the violence was perpetrated by white Americans against Indians and other minorities. In 1970 Little Big Man showed a glory-hunting, insane George A. Custer slaughtering Indians at the Washita and soliloquizing like Hamlet at his death scene at the Little Bighorn. Soldier Blue gave us a similarly crazed John Chivington butchering Indians at Sand Creek.

Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee served to fan the flames. The times were ripe for the book, and it trampled the one-time soldier and cowboy heroes into the dirt. The Indian was raised to the status of patriot hero, and perhaps unwittingly, into the perpetual victim. It was a good story, but bad history, and by then, people didn’t seem to care—or know the difference. America had been “dissed,” and the disparagement only got worse. Films such as Dances With Wolves followed the trend. By now, almost all whites, save a precious few, were depicted as murderers or crazy. Even the new victims, the Lakotas, were being picked on by the Pawnees!

Just how far the situation has deteriorated is evidenced in the 2005 TNT production Into the West. The concept for Into the West is similar to How the West Was Won. The former is divided into six episodes: “Wheel to the Stars,” “Manifest Destiny,” “Dreams & Schemes,” “Hell on Wheels,” “Casualties of War” and “Ghost Dance.” It traces the conquest of the West through the eyes of the white Wheeler family and a family of Lakotas. The concept is good. Telling the story of the Western movement needs the balance of various viewpoints. Beyond this, the gulf between the two films is enormous.

In Into the West, minorities—Hispanics, Indians and women—are all victims of corrupt, murderous, power-hungry, racist white men. As in so many of the films that preceded it, nearly every soldier is depicted as egoistic or mentally unbalanced. Facts about major confrontations at Sand Creek, Washita, Little Bighorn and Wounded Knee are seriously distorted to make the soldiers appear in the worst light possible. There are enough incorrect details to drive a student of Western history to distraction.

Take the Sand Creek affair, for example. The bodies of the murdered Hungate family were displayed in Denver in June 1864, not in September. Colorado Territorial Governor John Evans didn’t authorize formation of the 3rd Colorado Cavalry. Colonel John Chivington was not in command of the 3rd—George Shoup was. The words spoken at the Camp Weld Council were misrepresented. In reality, Evans all but promised the Indians that winter was his time for fighting—that they would be attacked. The Indians came away from the council knowing that no peace was made. They told John Prowers so. While the Indian chiefs were in Denver talking peace, their villages and warriors were in Kansas raiding and battling the soldiers. Chivington was under direct orders to attack the Indians. Even so, he did not attack peaceful bands. Chief Friday’s Arapahos, for instance, were camped much closer to Denver, but Chivington did not go after them. He went after the guilty ones. The Indians had never been living on the Sand Creek Reservation, and they were not on it on the day of the battle. They were not peaceful, but had been raiding, raping, killing and capturing all summer. They had seven white captives in the village until shortly before the battle. Three women were beaten and raped, but Into the West makes no mention of them. Major Edward Wynkoop did not give an American flag to Black Kettle. Wynkoop was not even at Sand Creek. There was no mounted charge through the village. Chief White Antelope was not killed stoically standing in front of his tepee holding his peace medal. The first two people killed in the battle were soldiers shot down by the Indians. The Indians fled the village before the soldiers got in. There is no mention of the 76 soldier casualties—one of the highest casualty counts in the Indian wars. Black Kettle did not walk out of the village carrying his wounded wife. He abandoned her and fled. The soldiers did not kill all; they captured and saved about 10 Indians and mixed bloods, plus a few whites who were in the village trading. In summary, the Indians were not peaceful, they were not under protection, and they were not killed in the village.

This type of distortion is rife throughout Into the West. Custer’s words about waiting for reinforcements before the Battle of the Little Bighorn are purposely altered to show the 7th Cavalry commander in a poorer light. The Indians did fire first at Wounded Knee, contrary to the film’s depiction. One might read historian Robert Utley’s Last Days of the Sioux Nation for an understanding of the true sequence of events. The Indian school at Carlisle, Pa., conceived by a good man like Richard H. Pratt, is shown to be no better than a concentration camp run by Gestapo-like guards. One might even complain that the clean-shaven mountain man, Jedediah Smith, is always incorrectly shown as bearded and dirty.

Misrepresentation and playing loose with the facts are the bread and butter of Into the West. It gets nearly as much wrong as right, and its sole purpose appears to be to pile a guilt trip on Americans. Where How the West Was Won was idealistic, optimistic and bright, Into the West is nihilistic, pessimistic and bleak. Even the score is melancholy, bordering on a funeral dirge, and the screen is painted in somber colors. In the final scene, the heads of the main white and Lakota families tell their children the “tale” of how the West was won, which would smother one family with shame and guilt and paint the other as perpetual victims. It is not a happy denouement for either side.

Neither How the West Was Won nor Into the West gives a true picture of the westward movement. The former was guilty of omission, rather than distortion, while the latter was guilty of distortion, rather than omission. There is little doubt in my mind which view is healthier. Where did TNT and one-time Crockett fan, executive producer Steven Spielberg, get their jaundiced views of history? A companion volume to the film Into the West was written by Max McCoy, and although it does warn that it is “a work of fiction,” the folks watching the film are not given that red flag. They are likely to believe what they are seeing is true, and they probably will, given the constant bombardment of politically correct history the post–baby boomer generations have been force-fed during the past four decades. Into the West may have generated from suspect origins and, like Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Topsy, just “grow’d.” It seems to belong to what may be termed the “Everybody Knows” school of history. The “facts” are suspect, but somehow, everybody knows they must be true. The propaganda has had its effect. It is history by repetition. If you hear it or see it enough, it becomes true by volume alone.

“Everybody Knows” history is closely related to history by popular vote. Americans have a penchant for putting truth to the vote test. It is said that about two-thirds of Americans believe that John F. Kennedy was a victim of a conspiracy. That doesn’t make it true. A majority of Americans are also said to believe that the earth has been visited by space aliens. The proposition that we can vote on truth is ludicrous, and it follows that history should not be written or taught with such shoddy methodologies.

Have we progressed in understanding from How the West Was Won to Into the West? Very doubtful. The history portrayed in the latter is no better, and is arguably worse, than the old versions. The disparagement of America is self-destructive, but the dark view of our past that Into the West presents is only a manifestation of our times. The generational cycle will inevitably shift, and, again, one day we will take pride in our ancestors and ourselves and see hope in the future. Until then, keep repeating, “It’s only a movie….”

Originally published in the June 2006 issue of Wild West. To subscribe, click here.