The incredible story of thousands of soldier photographs and letters that never made it home

A young Civil War soldier gazes back at me from a carte-de-visite, a playing card-sized photograph I recently purchased. He has a steely look, and his right hand grasps the lapel of his military dress coat. His left hand, in his lap, wears a ring. A small fur cap, a winter luxury, sits atop his head. I don’t know who he is. He’s unidentified. And when I look at him, I wonder if he posed for the photograph to let someone special back home know the fur cap had arrived in camp. If so, they never got the message. Because this photograph, like thousands of others, bears the characteristic marks—an identifying number written in red ink and the traces of brass mounting clips—of having ended up in the Dead Letter Office.

During the Civil War years, hundreds of thousands of young men left home for the front lines, traveling out of their state or hometown for the first time in their lives. Unaccustomed to the separation and the sometimes-stifling loneliness of war, they wrote home. But many were poorly educated or had never even addressed a letter, and the recipient’s name and address on the envelopes were undecipherable. Sweeping changes to recent postage requirements and the interruption of mail in the seceded states also heavily impacted the delivery of letters. Those letters that could not be delivered, for whatever reason, were processed by the Dead Letter Office.

Established in 1825, the Dead Letter Office, located in Washington, D.C., was designated to investigate undeliverable mail, with the intent of getting it to its intended recipient. DLO clerks were exclusively granted by Congress the ability to open mail to examine its contents for further clues as to the proposed destination. Still, regulations allowed clerks to read only the bare minimum to try to parse out names, locations, or other identifying information. These clerks needed a keen knowledge of geography and colloquial use of language to aid them in their pursuit.

During the mid-19th century, most of the dozen or so DLO clerks were women and retired clergymen. They were believed to possess a superior moral character and could therefore be trusted with the cherished and sometimes priceless contents of these dead letters.

Great care was taken to protect and return as many letters as possible, especially those with any monetary value.

“A ‘money letter’ has five different records before it leaves the Dead Letter Office and is so checked and counter-checked as to make collusion or abstraction almost impossible, in case any soul who surveyed it were fatally tempted,” according to Mary Clemmer Ames in her 1874 book Ten Years in Washington: Life and Scenes in the National Capital, As a Woman Sees Them, which documented the inner workings of the Dead Letter Office.

For items such as advertisements or circulars, or those that were never claimed or could not be delivered, the clerks oversaw their disposal—except Civil War soldiers’ photographs. Although these items technically should have been disposed of, according to Lynn Heidelbaugh, a curator at the Smithsonian National Postal Museum, they never were. And, driven by a sense of patriotism or devotion, one supposes, to the men who served the Union cause, the DLO continued to try to reunite them with their intended recipients, long after the war ended.

Enclosed with letters home, the photographs came in the form of cartes-de-visite or tintypes. Most were of a single soldier, maybe posed in front of a military-themed painted backdrop and decked out in full kit, ceremoniously documenting his participation in the monumental war raging on the nation’s own soil. Some photographs included more than one soldier. Brothers, maybe? Friends from back home? Did they all know the recipient, or was the photograph meant as an introduction to a new comrade who kept the soldier company during the homesick days of war?

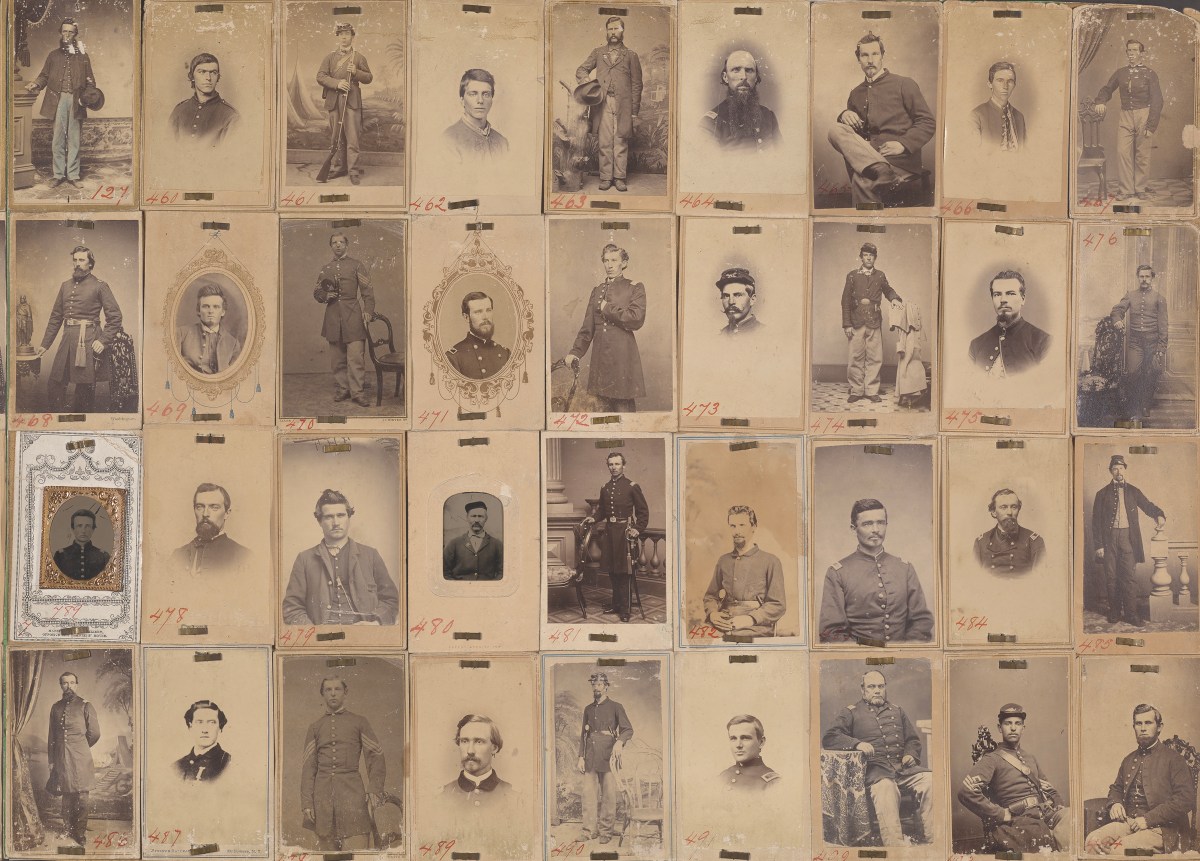

By the end of the conflict, thousands of these photos remained undelivered, with most estimates around 5,000. They lingered in a portfolio of sorts in a Post Office storeroom, with little hope of finding their destination, until Third Postmaster General Alexander Zevely, who served from 1859-1869, conjured up an innovative idea—he ordered them to be displayed in the Dead Letter Office Museum.

The Dead Letter Office Museum housed an eclectic combination of items that represented both the Post Office Department’s history and showcased some of the more curious objects that passed through the DLO each year, including unusual trinkets, loaded pistols, various bottles and boxes, and even a skull.

The museum was an oddity and a popular tourist attraction, which Zevely hoped would help put more eyes on the soldier images. At his request, the portraits were attached to panels with brass clips in groups of 36 images, or four rows of nine images each, and numbered with those telltale red-ink numerals.

Museum visitors would scan the image panels and the thousands of stranded faces they displayed, seeking a brother, a husband, a father, a neighbor, a sweetheart, often one lost to the war. The display itself was a moving tribute to the military men who had sacrificed years and sometimes their last full measure of devotion to the Union. They included soldiers, sailors, officers, young and sometimes old. They posed with rifles and sabers, pistols crammed into their standard issue leather belts, cartridge boxes strung across their chest. They donned kepis and Hardee hats and represented states East to West. Some men looked fresh and keen. Others appeared war-weary, with worn brogans and tattered sack coats. It was a stunning display of the Union front line.

When a familiar face presented itself, a loved one would claim it by number. A clerk would remove the image and write in its place on the board the date of its removal and the name and location of the person receiving the image—at long last going home. On June 17, 1874, Mr. F. Poplain claimed the photo of Lieutenant S. Roderick of the 19th Iowa Infantry, according to an extant panel. On October 16, 1902, Edward Marsh of the 10th New York Battery claimed a photo of himself, some 40 years after he had placed it in the mail. It is impossible now to say how many of these often-emotional reunions occurred, but some estimates put the number as high as 2,000.

The Dead Letter Office also advertised descriptive lists of the photographs in newspapers and journals of the Grand Army of the Republic. In the early 1890s, the photographs and panels were cleaned and bound into an album, one panel per page. At this time, the DLO also began working with veterans’ groups to track down the descendants of any of the photographs that might have identifying information on it. The G.A.R.’s Meade Post in Philadelphia, for example, inspected the photographs and removed all those with inscriptions, then turned them over to G.A.R. headquarters in Washington, D.C., for further help identifying them and delivering them to their rightful owners.

These extraordinary efforts to reunite the soldier photographs with their recipients, went “above and beyond the standard operating procedure” of the DLO, says Heidelbaugh. “I think it shows how deep the scars of the war were for the United States and that people were dealing with the aftermath very personally and in a very tangible way.”

Bound in an album, these photographs could also now travel, and the Dead Letter Office took the opportunity to exhibit the album at world’s fairs across the country, where new sets of eyes could peruse the thousands of soldier photographs that remained unclaimed. At the 1898 Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition in Omaha, Neb., the daughter of Civil War veteran J.J. Gorman claimed her father’s photograph, which had been sent during the war, from Indianapolis to South Bend, while he was serving with the 86th Indiana Infantry. It had been in the DLO exhibit for 35 years, according to a report about the fair.

Held for Postage

In the summer of 1861, two consequences of the war significantly increased the volume of mail ending up at the Dead Letter Office in Washington, D.C.: Soldiers sending letters without proper postage and the shuttering of federal post offices in the seceded states. Before 1856, letters could be sent “postage due” and the cost of mail delivery would be collected from the recipient. In 1856, however, a law was passed that required prepayment of all mail with postage stamps. Those letters without proper postage would be “held for postage.” The sender, if identifiable, would be notified of the postage due. If left unpaid after a brief period of time, however, the letter would now be sent to the Dead Letter Office. On May 1, 1861, a new post office regulation further eliminated the notification to addressees to prepay the postage and the letters were immediately delivered to the Dead Letter Office. With so many soldiers in camp lacking the money to buy postage stamps or any place to buy them, the influx of these unpaid letters to the Dead Letter Office was stifling. In his annual report of 1861, Postmaster General Montgomery Blair wrote, “By immediately sending this class of letters to the dead letter office, it was expected that a proper compliance with the law would be enforced, but so far from this being the case, the number after one year’s trial exceeds ten thousand each month, and the attention they require imposes considerable additional labor and expense on this department.” In 1862, Third Assistant Postmaster General Alexander N. Zevely sought to curtail the situation by creating a “Soldier’s Letter” stamp which would move dead letters identified as originating from a soldier through the delivery process despite a lack of proper postage. Second, at the behest of Blair, mail service in the seceded states was suspended May 31, 1861, just before the Confederate Post Office Department assumed control of its own postal system on June 1. Much of the mail intended to move between the North and the South ended up in the Dead Letter Office as undeliverable or unpaid mail. In his 1861 report, Blair said, “From the 1st of June to the 1st of November there were received at the dead letter office, in consequence of the suspension of postal communication, 76,769 letters, originating in loyal States, and addressed to residents in disloyal States. Of this number, there were returned to the writers, 26,711. During the same period 34,792 foreign letters, destined for that section, were returned as ‘dead,’ and 2,246 of them were delivered in the loyal States to authorized agents of the parties addressed, making the whole number sent out 103,886, which is considerably more than three times the quantity sent out during the previous year, when the number was unusually large. In addition to the above, about 40,000 letters from disloyal States, addressed to parties in the loyal States, were sent to the dead letter office after the suspension of the postal service, a large proportion of which were forwarded to their destination.” The Confederate Post Office also designated a Dead Letter Office, which was located in Richmond, Va., although records indicate most of the mail that ended up there was destroyed. –M.A.W.

“There is a melancholy collection from the dead letter office, including two cases of photographs of soldiers which were sent and miscarried during the Civil War,” noted a reporter for the local Omaha newspaper. “Looking at them, I thought how young were most of the faces….”

The fairs offered some new success stories, but with several decades now since the war had passed, they were few and far between.

In 1911, the Dead Letter Office Museum closed. The album of soldier photographs lingered in the Dead Letter Office for a time, still available for the now infrequent observer, but by the 1930s it was placed in storage. In the 1940s, embroiled in World War II, the government decided to free up storage space at the Post Office building and the album was divided and sold. In 1948, collector Philip Medicus sold 10 panels, with about 360 photos, to the George Eastman Museum, in Rochester, N.Y., where they remain today.

Photography Becomes Affordable

Two mid-19th century inventions, the tintype and the carte-de-visite, made photographs affordable and accessible to a general population. Invented in 1856, the tintype is not actually tin at all, but iron. The term was a nickname for the more technical- sounding ferrotype and the hard-to-pronounce melainotype. An improvement upon the earlier ambrotype technology, in which a negative image was exposed on a glass plate and the back painted black for the picture to be viewable, tintypes used the same process but substituted a less expensive iron plate blackened by Japan varnish. The medium reached its peak use from 1860 to 1865. The carte-de-visite, named for its resemblance in size to the popular visiting card of the era, is a photograph printed on paper, then mounted on cardstock. Unlike earlier photos which were one of a kind, these images were made using a negative and thus could be produced in quantity. The technique was known as an albumen print since the picture was created using a glass negative on paper that was coated with egg white. Invented in 1854, cartes-de-visite were sold by the dozen. By the early 1860s, the U.S. had experienced a craze in collecting and exchanging these “card portraits.” Easy to tuck into an envelope with a letter home, they were particularly popular with Civil War soldiers. The height of their use was between 1859-1870. –Heidi Campbell-Shoaf

Argus Ogborn, an Indiana collector, sold off his collection of about 1,400 DLO photographs in 1982. He recorded his name and a catalog number on everything he collected, including his hundreds of DLO cartes-de-visite. His name and “No. 409” can be found on the back of almost every DLO image that passed through his hands. They still turn up on the collector’s market today, where undelivered DLO photographs continue to circulate, still traveling far from their intended destination.

“They were lost in the mails of the 1860s and never found their rightful owners,” says Dave Taylor, who purchased most of Ogborn’s collection from him. “With any luck, today’s owners will appreciate them as individual pieces of Civil War history that have finally come to rest in their proper place.”

During the Civil War, the Dead Letter Office was located in the General Post Office building in Washington, D.C. Designed by architect Robert Mills, it was opened in 1842, and was the first all-marble clad exterior in the capital. In 1855, Thomas Ustick Walter, the architect who designed the Capitol dome, began to oversee the General Post Office’s expansion, which was halted during the Civil War, while the Union used the building’s basement as munitions storage. Walter’s addition was completed in 1866 and Union Quartermaster General Montgomery C. Meigs engineered the addition’s inbuilt mechanical heating and cooling system. In 1917, during World War I, the accumulation of mail ending up in the Dead Letter Office again became suffocating, and the now more complicated delivery of it throughout the expanded United States prompted the Dead Letter Office to set up satellite offices across the country. It was the first time all dead letters were not directed just to Washington, D.C. Eventually, most of the satellite offices became obsolete and were shuttered, including the Washington, D.C. office. Today, the Dead Letter Office exists as the USPS Mail Recovery Center in Atlanta, Ga.

“They are very touching,” says Ronn Palm, who owns and displays one of the panels with many of the DLO images still attached to it at his Museum of Civil War Images in Gettysburg. “The letter that never made it. The story that never got told.”

In my own personal collection, in addition to the soldier with the fur cap, I have a dozen or more of these poignant images. They seem to hold on to a peculiar sense of loneliness—a sentiment, interrupted. Their faces proud, or stoic, jovial, or determined. Some of them reveal the lost eagerness of a youthful boy who has “seen the elephant.” They were fathers, sons, husbands, brothers, lovers. I wonder what parting words of affection they meant to deliver that never were said. I wonder if the soldiers ever made it home, even though, despite the valiant efforts of a healing nation to deliver them, their photographs never did.

Melissa A. Winn is the Director of Photography for Civil War Times magazine, a writer, and a collector of Civil War photographs. She thanks Kurt Luther, Ph.D., Virginia Tech, for introducing her to Dead Letter Office images and informing some of the research used here on the topic.