A Congressional committee kept a close eye on Union generals

Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War ranks among the indispensable sources on the Union war effort. Published in eight volumes between 1863 and 1866 and reprinted and indexed by Broadfoot Publishing in 1998, this set consists of more than 5,000 pages of testimony and other documents relating to military campaigns as well as to such topics as alleged misconduct in the area of supply. Virtually every senior Union general gave testimony before the committee, addressing Gettysburg and Antietam, the campaigns in Tennessee and along Louisiana’s Red River, First and Second Bull Run, Ball’s Bluff, and many other operations. Witnesses appearing before the committee often sought to justify their own actions or to damage the reputations of others. Their testimony consequently reveals a good deal about factions within the Union high command, but it also contains a vast amount of useful detail about the planning, execution, and contemporary analysis of Union military affairs.

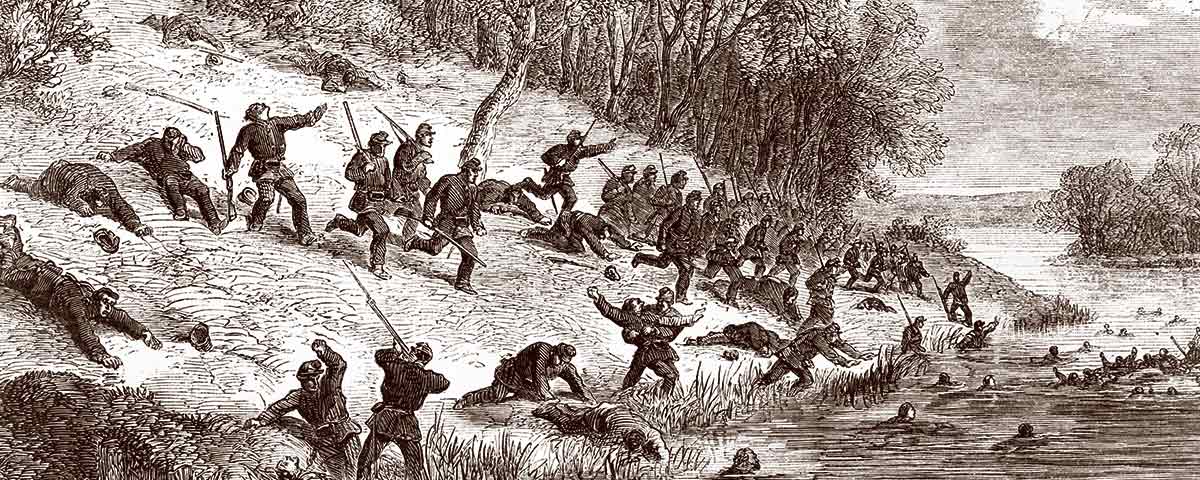

The Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War (JCCW) emerged out of the intensely fractious political atmosphere of late 1861. Ignominious defeat at First Bull Run on July 21 and the galling debacle at Ball’s Bluff on October 21 shook loyal citizens. The removal of John Charles Frémont from command in Missouri, where he had tried to strike at slavery and slaveholders, alienated Radical Republicans and abolitionists. Perhaps most important, George B. McClellan’s failure to mount an offensive during the late summer and autumn prompted some congressional Republicans to question the ability and even the allegiance of many Democratic generals. The death at Ball’s Bluff of Colonel Edward D. Baker, a Republican senator from Oregon and close friend of Abraham Lincoln, prompted a group of politicians to train an accusatory spotlight on Brig. Gen. Charles P. Stone, and he became a scapegoat for Baker’s lack of military ability at Ball’s Bluff and for Republicans unhappy with the war’s progress.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]The committee inspired heated reactions from supporters and critics[/quote]

A group of Republican senators and congressmen feared that professional soldiers of McClellan’s and Stone’s stripe would not wage hard war against the Rebels. Especially unhappy were Radical Republicans who hoped the conflict would kill slavery as well as restore the Union. On December 5, Senator Zachariah Chandler of Michigan called for creation of a joint congressional committee to examine events at First Bull Run and Ball’s Bluff. Established on December 10, the seven-man committee consisted of senators Chandler, Benjamin F. Wade of Ohio, and Andrew Johnson of Tennessee, together with congressmen George W. Julian of Indiana, John Covode of Pennsylvania, Daniel W. Gooch of Massachusetts, and Moses Fowler Odell of New York. All were Republicans except Johnson and Odell, and Wade (the chairman), Chandler, Julian, Gooch, and Covode were Radicals. Although composition of the committee changed as the war progressed, Radicals remained a powerful force in its activities.

Members of the committee considered it part of their role to provide congressional oversight of the Lincoln administration’s military policies. They consistently called for offensive campaigns and demanded the removal of George B. McClellan; several also sought to drive George G. Meade from command of the Army of the Potomac, attacked other commanders deemed too timid or too Democratic, and championed officers such as Joseph Hooker and John Pope whose politics they found more congenial.

Lincoln struggled to forge policy amid cacophonous demands put forward by constituencies extending from the Radicals on one end of the spectrum to conservative Democrats on the other. As early as the fall of 1861, before the committee was formed, Lincoln’s secretary John Hay noted in his diary that Chandler, Wade, and others in the “Jacobin club,” as Hay called the Radical Republicans, had been criticizing McClellan’s lack of action and trying to “worry the administration into a battle.” In their postwar history of the Lincoln administration, Hay and John G. Nicolay described the committee as “often hasty and unjust in its judgements, but always earnest, patriotic, and honest.”

The committee inspired heated reactions from supporters and critics. Democratic officers called to testify typically expressed a mixture of anger and concern. On February 28, 1863, for example, McClellan, removed from command of the Army of the Potomac the preceding November, described a difficult day to his wife. “I have just got back from that confounded Committee & have to appear before them again on Monday morning,” he wrote. “I have been under their hands for several hours & you may imagine that my brain is rather tired out.” Just more than a year later, Meade confided to his wife that he detected “nothing less than a conspiracy” to remove him from command of the army.

Unlike McClellan, Meade retained his military position but nevertheless nursed a grudge against the politicians he saw as partisan tormentors. Democrats in general came to characterize the committee as a biased body that hounded honest officers and tried to transform a war to restore the old Union into a crusade to kill slavery.

On the Republican side, Radicals believed the JCCW served a necessary purpose to make the United States move quickly and apply its full resources against the Confederacy. Many moderate Republicans, in contrast, viewed the Committee’s actions with mixed feelings.

Students of the Civil War should be thankful for the JCCW’s Report. Here is much of the story of how the North struggled to define its objectives, find its leaders, and construct a winning strategy. Debates over the fate of slaves who made their way to Union lines, whether to add emancipation to the nation’s war aims, and how harshly to treat rebel civilians and their property all figure prominently in the Report. Indeed, a full understanding of the political and military history of the Army of the Potomac is impossible without reference to the Committee’s evidentiary record, as is a proper appreciation of the degree to which George B. McClellan dominated much of the early-war period.

It is no exaggeration to state that few published sources so clearly illuminate the often chaotic process by which the United States struggled to manage an event of cataclysmic proportions. ✯