Early one morning in fall 1941 Takeo Yoshikawa encoded a brusque telegram for the Japanese foreign ministry’s home office in Tokyo. In its entirety, the message read: “Details unclear.” It was an admission of failure, and Yoshikawa’s apparent testiness is easy to understand. The 27-year-old intelligence officer had spent much of the previous evening submerged in the shallows of Oahu’s Mamala sey, attempting to study submarine barriers at the entrance to Pearl Harbor, only to come away with nothing but a deep chill.

His superiors in Japan had ordered him to get information on the barriers’ dimensions, formidability, and operation. Lacking any other source for the information and unable to view the underwater apparatus from afar, he decided to make an exploratory dive. To look like a local, or perhaps a Filipino laborer, he approached Ewa Beach shoeless, through a thick growth of elms. The undergrowth tore at his bare arms and the rocky, volcanic soil cut his feet. After dodging a Marine putting out his laundry, Yoshikawa made it to the water’s edge.

In the encroaching evening, the water was smooth as glass. Any disturbance of the surface would be immediately apparent. Despite his misgivings and the sting of the saltwater on his fresh wounds, Yoshikawa entered the bay and swam toward the mouth of Pearl Harbor. When he got near, he spotted a sentry and took up position underwater, holding a large rock to keep from surfacing and breathing through a pipe, which he had rigged with a periscope and camouflaged its exposed end with driftwood twigs and leaves.

He knew there would be no way to explain his presence if he was caught, so he remained submerged as long as he could. The tropical waters, while perfect for a casual dip, were cold enough to leach the heat from his lean, unmoving body. In the growing darkness, the sentry became increasingly difficult to see; Yoshikawa’s mind began to wander. Eventually, he imagined that he could hear the sentry and heard him leave. When he finally surfaced, the sentry was gone—but his work was done: he had thwarted Yoshikawa’s reconnaissance attempt. Shivering, half drowned, and covered in scratches, the spy made his way back to the Japanese consulate in Honolulu in the dead of night, defeated.

Or at least that was Yoshikawa’s story.

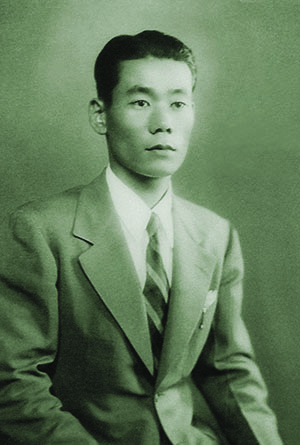

IT IS IMPOSSIBLE TO KNOW what really happened, and inadvisable to take Yoshikawa’s word for it. The former Imperial Japanese Navy ensign—then posing as a clerk at the consulate—was an unreliable narrator.

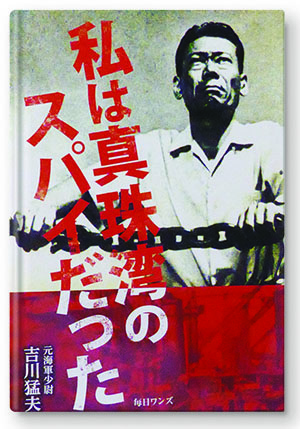

Yoshikawa recalled his espionage exploits numerous times after the war—in two full-length memoirs (one published in 1963, the other in 1985), along with newspaper and magazine articles and in interviews with American and Japanese writers, reporters, and historians. At various times he recalled the same episodes differently, and in all of his accounts, pretends to personal qualities his actions clearly belie. Complicating matters further, although Yoshikawa died in 1993, a Japanese publisher dealing mainly in nationalist tracts, Mainichi Ones, issued a revised version of his memoir in 2015 that made Yoshikawa’s story more nationalistic and, superficially at least, more plausible. An account of the Mamala Bay excursion occurs in all Yoshikawa’s full-length memoirs, richly detailed and casting him in a heroic light while explaining away his inability to obtain information on Pearl Harbor’s submarine defenses—one his few failures during his mission. Some measure of skepticism is in order.

Nonetheless it is possible, by combining what is known from American intelligence sources and Yoshikawa’s own recollections, to piece together a portrait of the man and his mission. The exercise is worth the effort, because Yoshikawa was indisputably effective as a spy. His activities made a direct contribution to the Japanese victory at Pearl Harbor.

YOSHIKAWA HAD ASPIRED TO BE a naval aviator, but a debilitating stomach ailment sidelined him during training. In 1936 at age 22, fearing his career was over before it started, he gratefully accepted an offer to enter the Japanese Imperial Navy’s intelligence section. He immersed himself in the study of English and read anything he could on the U.S. Navy, its warships, its bases, and its strategies and tactics. He took particular pride in his mastery of works by American naval theorist and sea power advocate Alfred Thayer Mahan, later boasting, “I can still quote much of Mahan from those days.”

In 1940 the Imperial Navy charged him with his fateful mission to Pearl Harbor, which he called “a half-year of furtive existence in the twilight world of the spy in which all men are enemies and fear walks always beside one.” First, however, they seconded him to the foreign ministry, where he was to grow his hair out and learn the arts of diplomacy to establish his cover. The following year they sent him under official cover-—as a diplomat named Tadashi Morimura—to the spacious consulate general in a quiet Honolulu neighborhood. There only the consul general, Nagao Kita, knew of Yoshikawa’s true mission.

Yoshikawa collected information anywhere he could find it. He scoured newspapers and community bulletins for scraps of useful facts. He chatted up servicemen and bought them drinks. On the pretense of taking casual strolls, he reconnoitered around military bases and Oahu’s major beaches, exploring them for possible landing sites. He gathered intelligence on the depth of Kaneohe Bay and natural obstacles in the harbor by the simple expedient of taking a glass-bottomed boat tour. He repeatedly observed the island from the air in sightseeing trips, taking pains to bring along a different woman each time to give the impression that he was little more than a playboy with a successful MO and limited imagination. He established observation posts in secluded sugarcane fields, and in or near the establishments of friendly Japanese immigrants—the Nikkei.

The information he collected gave attacking Japanese pilots an excellent idea of what they were up against. Detailed documents recovered from downed enemy aircraft led investigators to conclude that Japan had spies on Oahu, including “persons having no open relations with the Japanese foreign service.” Their report made many Americans imagine a far more extensive spy network than had ever existed, and ultimately contributed to the paranoia that led to the internment of more than 120,000 Japanese and Japanese American residents from the West Coast of the continental U.S. (although, ironically, sparing those in Hawaii).

In his postwar writings, Yoshikawa consistently took pains to absolve the Nikkei, and especially the Nisei—the American-born offspring of Japanese immigrants—of rendering him assistance. “Hawaii’s Nisei shared a deep sense of belonging to the United States,” he wrote with apparent chagrin; when entreated to do something for Japan, “They would refuse me with the line, ‘I am an American.’” However, it is indisputable that without the aid—witting or otherwise—of some Hawaiian Nikkei, Yoshikawa would not have been nearly as successful.

One who helped him was Taneyo Fujiwara, the proprietress of a Japanese teahouse, Shinchōrō, which commanded an excellent view of Pearl Harbor and was equipped with a substantial telescope. Yoshikawa used the telescope extensively, and often—after feigning drunkenness—spent the night unsupervised in the room where it was kept. (Interested readers can see the instrument at Shinchōrō’s successor establishment, Natsunoya Tea House, run by Laurence Fujiwara, Taneyo’s grandson.)

Another Nikkei who assisted him was John Mikami, a taxi driver the consular staff often employed. Yoshikawa befriended and hired Mikami for frequent sightseeing trips. Though Yoshikawa never informed Mikami of his mission, the cabby seemed to have divined the purpose of Yoshikawa’s excursions and went out of his way to point out details of military significance or show Yoshikawa vantage points for observing Oahu’s military installations. Once Mikami took the spy to Schofield Barracks, command headquarters for the U.S. Army in Hawaii and home of the 25th Infantry Division. They somehow got onto the grounds and Mikami showed Yoshikawa around before heading for the exit, where he casually told the guard he had been attempting to take his fare to a tourist destination. The guard waved them on, despite the fact that Schofield is in the interior of the island far from any tourist attractions.

At least one person offered Yoshikawa knowing aid—German spy Bernard Julius Otto Kühn, whom German military intelligence had dispatched to assist the Japanese—but Yoshikawa resisted it. Under Yoshikawa’s protests Nagao Kita had ordered him to meet with Kühn and pay him on multiple occasions.

Brushes with American authorities and his frequent presence near sensitive facilities notwithstanding, Yoshikawa was careful to stay on the right side of the law, or as close to it as he possibly could. “Espionage essentially is at bottom an unromantic exercise in research methodology,” he said. “It is all there if you will only take the trouble to dig for it.”

He dug relentlessly—but cautiously and patiently as well. He never raised the suspicions of American authorities. They never even learned his real name. The only prewar mention of Yoshikawa in military intelligence files is a routine record about his visa status under his alias. Robert L. Shivers, the FBI’s man in Honolulu from August 1939 until April 1943, cultivated extensive contacts in Japan’s Nikkei community. But in his memoirs he admits that he never suspected Yoshikawa.

Yoshikawa maintained that he had no foreknowledge of the timing of the attack on Pearl Harbor, and it is likely he did not know anything concrete. The raid’s naval planners were stingy with information; even Prime Minister Hideki Tōjō did not learn the details until after the fleet had sortied. Nevertheless, Yoshikawa certainly suspected an attack was imminent. In the first week of December he burned the notes, clippings, and photographs he had used to compile his reports. On December 6, Yoshikawa settled outstanding debts and treated Mikami to dinner at Shinchōrō. But some sensitive materials remained in the consulate’s locked code room. After the attack he had to await the arrival of the consulate’s cipher clerk, who had the only keys. American authorities turned up before he could burn all the evidence and caught him with a detailed, if only half-finished, hand-drawn map of Pearl Harbor. Yoshikawa’s luck had run out.

IN THE IMMEDIATE AFTERMATH of the attack, American authorities confined the consular personnel to the compound grounds, and quickly arrested Kühn, whose extravagant spending habits had caught their attention. The German spy provided the Americans with a description of his Japanese paymaster; the Americans suspected Yoshikawa was the man. Still, considering the magnitude of the disaster they had suffered and that authorities were even then preparing to round up innocent Nikkei from the West Coast, they went remarkably easy on Yoshikawa.

Authorities eventually interned the consular staff in a comfortable—if remote—ranch in Arizona. Given the situation, their captors afforded them every courtesy; Yoshikawa and his colleagues could play tennis, use the sauna, get cocktails, and—if not for the uncertainty of the future—generally enjoy the good life. Yoshikawa found himself wondering if Americans interned in Japan would receive such treatment.

In spring 1942 (Yoshikawa believed it was May), the inevitable finally came to pass. An investigator came to question the consular staff. It soon became clear that Yoshikawa was his focus. Through four days of interrogation the spy maintained his innocence. Even when confronted with the map, he did not relent, claiming he had drawn it for the purpose of sightseeing. After the fourth day, Kita came to see him. Based on the investigator’s line of questioning and on Yoshi-kawa’s suspicious activities at the consulate, the rest of the consulate staff had concluded that he was a spy, that the Americans knew it, and that as long as he denied it they were in jeopardy. They prevailed upon Kita to ask Yoshikawa to turn himself in. Shocked, Yoshikawa said he would think about it.

But Yoshikawa had no intention of falling on his sword. “My duty ended when the bombs fell on Pearl Harbor,” he explained. “After that it was out of my hands. I was in no hurry to die a dog’s death in some ridiculous exhibition of a spirit of self-sacrifice.”

This was not in line with his training. The Imperial Japanese Naval Academy had placed a premium on developing an ethic of self-sacrifice in its students—of perseverance until death. Yoshikawa instinctively recoiled from this. Despite his efforts to internalize self-denial through Buddhist meditation, he remained, in his own words, “afraid to die.”

Yoshikawa’s resistance to indoctrination, groupthink, and the romanticization of sacrifice would later cost him his position in the navy. In the short term, however, his sense of self-preservation paid off. The next day, the interrogator told Yoshikawa that he and his colleagues were free to go. The American had had only a week to crack the case and had failed. The diplomatic corps of the United States, Japan, and Sweden had worked out an exchange of personnel; Yoshikawa and his colleagues were taken to New York in preparation for departure to Japan.

The suspicions around the spy were strong enough, however, that the authorities sought to hold Yoshikawa, and only Yoshikawa, back. The head of the Japanese diplomatic mission to the United States, Admiral Kichisaburō Nomura, maintained that the full mission would return or no one would, scuttling the exchange. The Americans relented and allowed Yoshikawa to join his colleagues. He was the last to board the ship before it cast off.

At the neutral Portuguese port of Lourenço Marques in southeast Africa (present-day Maputo, Mozambique), the Japanese crossed paths with the former American mission to Japan. Yoshikawa noted that the Americans were disheveled, their bags of poor quality, and their appearances haggard. Rather than inspiring him to reflect on his own good treatment as a prisoner, the sight convinced him all the more of the necessity of struggling against the United States—which had so much power and wealth, his reasoning went, it could afford to squander it on captives. Insight of this sort coupled with moral myopia was characteristic of Yoshikawa. While he could discern injustice and evil, it rarely truly exercised him unless it applied to him personally.

After returning to Japan in August 1942 (accounts vary as to the exact date), Yoshikawa married, began a family, and continued naval intelligence work, mainly as an analyst. Because of his skill with English, he also interrogated Allied prisoners, condemning in his memoirs the savage abuse some of them received.

Yet neither the Japanese navy nor the government officially commended him for his contributions to the success of the Pearl Harbor attack—a sore point with Yoshikawa for the rest of his life. Eventually he ran afoul of his superiors. Sometime in June 1944 Yoshikawa surmised that reports of battle successes from frontline naval units were wildly exaggerated or wholly fabricated. He produced a more modest—more accurate—estimate based on Allied media reports and intercepted radio traffic, only to have his superiors accuse him of being “Americanized” and too credulous toward American propaganda.

Yoshikawa argued that if the frontline reports were accurate there would be no American warships afloat at all. But as was standard within the Imperial military at this time, politics trumped reality. Yoshikawa’s estimate was discarded. The Imperial Japanese Navy would lose three fleet carriers and more than 600 aircraft during a catastrophic defeat at the June 19-20 Battle of the Philippine Sea.

Yoshikawa resigned in disgust and spent the remainder of the war working at an aircraft plant. After the surrender, he made a small fortune on the black market before receiving word that Allied war crimes investigators were seeking him and other navy colleagues on suspicion of prisoner abuse. Believing that the United States simply sought revenge on the Japanese navy’s intelligence personnel, Yoshikawa went into hiding, spending four years at two Zen Buddhist temples until the trials were over. He drifted around the country until about 1950, then returned to his family to start a new life. He opened a gas station in Shikoku, but never reconciled himself to the new Japan of the postwar era.

Yoshikawa resigned in disgust and spent the remainder of the war working at an aircraft plant. After the surrender, he made a small fortune on the black market before receiving word that Allied war crimes investigators were seeking him and other navy colleagues on suspicion of prisoner abuse. Believing that the United States simply sought revenge on the Japanese navy’s intelligence personnel, Yoshikawa went into hiding, spending four years at two Zen Buddhist temples until the trials were over. He drifted around the country until about 1950, then returned to his family to start a new life. He opened a gas station in Shikoku, but never reconciled himself to the new Japan of the postwar era.

Shortly later, Gordon Prange, the chief historian on General Douglas MacArthur’s occupation staff, somehow learned of Yoshikawa’s historic role and tracked him down. The former spy agreed to an interview and went to see Prange in Tokyo just before the September 1951 negotiation of the San Francisco Peace Treaty that would mark the end of the occupation. In the early 1960s, a pair of other projects—an article Yoshikawa cowrote with Marine Lieutenant Colonel Norman Stanford, an assistant naval attaché in Japan, for the U.S. Naval Institute’s Proceedings magazine and a CBS News special he cooperated with to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the attack—led many right-wing nationalists to accuse Yoshikawa of selling out to the former enemy. Postwar anti-militarism was also near its height then, leading socialists, pacifists, and much of mainstream Japan to condemn him.

Yoshikawa lived out the remainder of his life subsisting on income from the gas station, his wife’s earnings as an insurance agent, and the proceeds from his memoirs and articles. He enjoyed enough esteem from his neighbors to be elected to the local town council twice. Nevertheless he became a bitter man. His memoirs are full of self-pity and bile. He faded into obscurity, a condition in which he died in 1993.

SINCE TAKEO YOSHIKAWA’S DEATH, his story has taken on new life—more recently in particular. A documentary on him by Japan’s national broadcaster aired in late 2014. The next year, the Mainichi Ones memoir appeared, altered to make Yoshikawa into a nationalist hero working for a righteous cause.

Yoshikawa, however, does not fill that role well. Though he displayed pride at his ability to help his country challenge the greatest power on earth, his authentic memoirs hint at doubts about the rightness of Japan’s cause. He describes tears coming to his eyes upon reading Japan’s declaration of war on the United States and the British Empire. But then he adds that upon rereading, he “could not help but think that it lacked a casus belli”—the Anglo-American transgressions against East Asia that it cited being “nothing more than backing Chiang Kai-shek.” His descriptions of captivity in American hands contain grudging acknowledgment that they treated him well. He displays something like regret about his role in making Japan’s attack a success and speaks of understanding the hostility Americans hold toward him.

The Mainichi Ones memoir has eliminated much of that ambivalence. We see Yoshikawa moved to tears by the Imperial Rescript, without the later doubts. His actions become more heroic. The volume “corrects” what its revisers (sometimes accurately and sometimes not) perceive to be errors in Yoshikawa’s original manuscript and distorts his narrative to make Americans seem more racist than Yoshikawa had ever implied.

In his authentic 1985 memoir, Yoshikawa describes how in Hawaii no one would sell rice to the consular staff, temporarily confined to the consulate grounds, because of their perceived involvement in the Pearl Harbor attack. In the 2015 revision, no one will sell rice to “Japs”—an unlikely prospect on an island where one-third of the population was of Japanese descent. Elsewhere Yoshikawa tells of being escorted through New York, where passersby mumble something about “Japs” under their breath. In the Mainichi Ones version, these people now shout the epithet in the captives’ faces.

Given that Yoshikawa changed his story and that that story has been altered since his death, there will always be some doubt about any part of it that cannot be independently corroborated. What can be said for certain is that Yoshikawa was a patriotic man from a naval background who conscientiously performed his assigned duties. Those duties, however, only helped his country commit to an ultimately disastrous course. This was something his country never let him forget during his lifetime, but now seems to be in the process of forgetting itself. ✯

This story was originally published in the December 2017 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.