Although ungainly looking, hard kicking and as stubborn as itself, the mule proved indispensable, if not heroic, to many prospectors, emigrants, soldiers and farmers on the wild frontier.

In the Wild West, a man could get hanged for horse theft yet thanked kindly for taking some- one’s no-account mule. The mule was, after all, an outrage against nature, a monstrosity, an unhappy cross between a donkey and a horse that possessed the qualities of neither. Mules had more kick than a Kansas twister. “Stubborn as a mule” wasn’t a cliché on the frontier—it was a statement of fact.

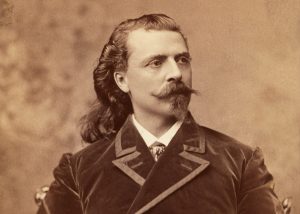

Elegant and dashing, horses stir the imagination. Ungainly and taciturn, mules more often dull the senses. Many Western enthusiasts have heard of Comanche, the U.S. 7th Cavalry horse that survived Custer’s Last Stand, and everyone of a certain age knows that Roy Rogers rode Trigger and that the Lone Ranger “rides again” on Silver. But mules, whether in the real West or the Hollywood West, largely remain nameless. Many people are aware, for example, that Brig. Gen. George Crook rode mules, but how many know that his favorite mule was named Apache?

Mules certainly get the short end of the stick, but hybrid beasts such as Apache were, in fact, four-legged unsung heroes out West. Much of the voiced criticism was tongue-in-cheek. The truth is that mules helped prospectors find gold, labored long in the hard-rock mines, pulled the majority of westbound emigrant wagons, transported most of the civilian and military supplies where wagons couldn’t go, and pulled plows on many of the prairie homesteads. What’s more, while Plains Indians clearly loved their horses, they liked mules, too.

In modern times, although singing cowboy Gene Autry rode a horse named Champion, he at least crooned “Mule Train,” listing every service the mule provided. The National Mule Memorial is the most popular draw in Muleshoe, Texas, which takes its name from a former local ranch. And baby boomers may remember Brighty, the heroic mule and title character of Marguerite Henry’s 1953 novel, Brighty of the Grand Canyon. Regardless, the mule remains woefully underappreciated.

Lacking the grace and form of the horse, the mule compensates with a mind of its own and far more stamina and common sense. As President Harry Truman once said, the mule “has more horse sense than a horse.” If horses helped romanticize the West, mules helped build it—by doing much of the dirty work.

Genetically speaking, a mule is the offspring of a male donkey and female horse. Ancient breeders discovered that this hybrid animal combines the patience, endurance and surefootedness of the donkey with the strength of the horse, making it ideal for heavy work. Tougher skin and harder hooves render it more adaptable than the horse to cold weather and difficult terrain. By comparison, the hinny, the offspring of a female donkey and a stallion, is a slower, weaker beast of burden.

The Spanish introduced mules as well as horses to the New World. In Spanish America, the mule was the primary draft animal, bearing everything from gold to grain on its back. It was bred in North America, often by missionaries, and became the riding animal of choice in old Santa Fe.

Some Americans who traveled west in the 19th century already knew the value of a mule (which had been bred in colonial New England), while others grew to depend on the Mexican mule, which was smaller but boasted greater endurance. The Santa Fe trade opened many eyes as to the worth of mules, and Missouri-based traders soon replaced their draft horses with the hybrids. During the California Gold Rush, mules proved their merit by packing supplies and ore to and from the mining camps.

Forty-Niner William Lewis Manly learned firsthand the value of a mule while passing through Death Valley en route to the California goldfields. His group had reached a sheer rock face at the edge of the valley. Out of water and unable to push on, the party sent Manly and his friend John Rogers in search of a spring or water hole. As the two men moved along the canyon face, Manly wrote, their mule “went on looking for every spear of grass and smelling eagerly for water, but all our efforts were not enough to get the horses along another foot.” Manly and Rogers were on the verge of despair themselves, when the mule “looked around to us and then up the steep rocks before her with such a knowing, intelligent look of confidence, that it gave us new courage.” Eventually, she led them to water, and the party was able to continue.

Manly and his friends had come up against the great obstacle that faced Forty-Niners—a lack of roads. As the Gulf Coast route curtailed the overland distance from the East Coast to California by half, gold seekers flooded into Texas, only to find wilderness beyond San Antonio. The government was already wrestling with the problem, and by the end of 1849, the Army established two practical routes from San Antonio to the Pecos River, and thence by a single road to El Paso. From there a well-prepared expedition could press on to California.

Although the Post Office Department was relatively indifferent to the needs of the frontier, the Gold Rush forced it to take action. Initially, lone riders carried the mail by mule between San Antonio and El Paso. Eventually, however, the department issued contracts to mule-drawn stage lines for scheduled service to El Paso, Santa Fe and other points throughout the Southwest. The “jackass mail” had arrived.

As travelers roamed farther from population centers, it became more difficult to acquire fresh teams. New York Herald correspondent Waterman L. Ormsby, who rode the first Butterfield Overland Mail coach between St. Louis and San Francisco in 1858, encountered this issue when the coach reached Sherman, Texas. The local agent’s teams, he wrote, “were so worn out in forwarding stuff for other parts of the line, that he had to hire an extra team of mules, at short notice, to forward the mail to the next station, and these were pretty well tired from working all day.” Mining settlements throughout the West relied on the services of mules. “A gold mining community does not ship much out, at least in bulk,” historian Watson Parker observed, “but a tremendous amount of material has to get shipped in.” The community required not only the essentials of life, but also hundreds of thousands of pounds of machinery. The Northwestern Express, Stage and Transportation Co. of St. Paul, Minn., hired 500 employees to run 1,000 wagons, 1,600 oxen and 600 mules between the railroad at Bismarck and the Black Hills. Freight rates from the railheads to the hills were $3 to $5 a pound, a substantial sum when one considers that freighter Fred Evans alone hauled more than 7 million pounds of machinery by mule train from Pierre in a single year (1880). The high cost of freight accounted for inflated prices on the frontier, which could soar to as much as six times retail.

Perhaps the most brutal fate awaiting a mule lay in the hard-rock mines. Western movie fans are familiar with the image of the lone prospector and his beloved mule trotting into town loaded with the bonanza of the diggings. The reality, though, was that serious gold mining required serious capital. When freelancers ran out of money, corporations stepped in, and mules were nothing more than equipment, no better than the ore carts they drew along rails deep in the earth. Blindfolded and loaded into slings, they were lowered down the shafts, never to see daylight again. By the dim light of candles and lanterns, they worked until they dropped, and were then dispatched.

Whether for mining or moving, good mules were often hard to find. Fast-talking con artists would outfit unwary greenhorns with wild mules, leaving the pilgrims to try and break them as a trip progressed. Well-trained mules were so scarce that even experienced handlers often had to make do with animals that were only partly broken. “We had a great deal of trouble in packing ‘green’ mules,” one Army officer remarked, “and much profanity was vented upon the air by our disgusted packers. It was a ridiculous sight—ob[s]tinate, ‘mulish’ mules, with heads covered with gunnysacks while packers were adjusting bundles and boxes.” Green mules would lie down on the job, and in the struggle to get them on their feet again, loads would shift and have to be repacked, only to have the mule walk a few paces and lie down again.

Experienced muleteers preferred the hardier Mexican mules to American mules. Just as the Indian pony had learned to live off the land, so the Mexican mule had adapted to survive on less than his American counterpart. Captain Randolph B. Marcy recommended the Mexican strain in his classic 1859 guidebook, The Prairie Traveler, after observing both types during a trip through the Rocky Mountains.

“For many days, they were reduced to a meager allowance of dry grass, and at length got nothing but pine leaves, while their work in the deep snow was exceedingly severe,” Marcy wrote. “This soon told upon the American mules, and all of them, with the exception of two, died, while most of the Mexican mules went through.”

Marcy also weighed the mule against the ox for pulling heavy loads over long distances. He preferred the mule in more populated areas, where good roads and grain were readily available, as mules traveled faster and endured summer heat better. Likewise, the mule was preferable on journeys up to 1,000 miles in areas where grass was plentiful. But on longer journeys, over sandy or muddy terrain, Marcy believed the ox held up better and was more economical. It was also less likely to be stampeded by Indians. As a final— if backhanded—endorsement to the ox, he wrote that, in a pinch, it could be slaughtered for beef.

There is no question the Plains Indians liked mules. Passing settlers and wagon trains needed reliable draft animals, making the mule a valuable commodity on the black market ruled by unscrupulous Eastern and Santa Fe traders. Thus the Indians would steal, capture or stampede mules whenever the opportunity presented itself. Even before wholesale westward expansion, American traders en route to Santa Fe found themselves dealing with the Plains tribes, most notably livestock-hungry Comanches and Osages. Sometimes these encounters were friendly; sometimes they were not. On June 1, 1823, a party of Santa Fe traders from Missouri lost their stock to Indians in a night raid at their camp on the Little Arkansas.

One of the traders, Joel P. Walker, recalled that when the two men watching the herd suspected Indians nearby, he told them to bring the animals into camp. “I had hardly given the order,” he wrote, “before bang! bang!! bang!!! went the guns of the Indians, who also stampeded our horses. I ran about a quarter of a mile, thinking some of the horses would stop. I then heard someone halloaing and saw the Indians driving horses.” The Indians escaped with 50 horses and mules, leaving the traders just nine between them.

The night stampede was a favorite Indian tactic, promising the best return for the least risk. When odds were overwhelmingly in their favor, the Indians would attack the party, gaining both animals and prestige as warriors. Mules were the plunder in the notorious 1871 Warren Wagon Train Massacre in northwest Texas, in which a Kiowa and Comanche raiding party killed seven teamsters and made off with 41 animals. Officials arrested three of the leading Kiowa participants and required the tribe to deliver an equal number of mules as an indemnity to wagon train owner Henry Warren. Ironically, two of those animals bore U.S. brands and were confiscated as government property.

Henry Warren’s mule trains hauled goods under contract. The train massacred in 1871 was hauling corn under a military contract to Fort Griffin, Texas. The Army was one of the most lucrative clients a freighter could have, as government mules were generally restricted to field expeditions and maneuvers. Private contractors handled military freight, as well as movement of government-owned wagons to far-flung military posts. As contractor Percival Lowe noted in 1862, “The transportation business at Fort Leavenworth [Kansas] was immense.” In July of that year, Lowe received an order to transport 600 horses and 120 wagons from Fort Riley, Kan., to Fort Union, New Mexico Territory, where wagons were in short supply. He put together five trains comprising 104 four-mule wagons and 16 six-mule wagons. Eight mules hauled additional forage. The 600 horses were divided into 18 strings. More than 250 men were hired to drive the wagons and manage the animals. The slower mules set the pace on the 622-mile trip, which spanned 30 days, including a two-day layover at Fort Lyon, Colorado Territory.

Mules would become synonymous with the military, hence the common phrase “army mule.” In the days before self-propelled vehicles, they served in virtually every capacity. Well into the 20th century, the Army used mules where vehicles could not travel or rail service was unavailable. Due to their proven stamina, mules substantially outnumbered horses on large-scale expeditions. While horses carried only cavalry troops, mules were jacks-of-all-trades, transporting supplies and provisions for both infantry and cavalry, as well as grain for themselves and the horses. Yet they recorded far fewer losses. For example, on General George Crook’s 1876 Big Horn Expedition, 58 of 656 horses succumbed to exhaustion, compared to just 32 of 892 mules.

Although Crook rode mules, more than a century after his death it is difficult to determine whether this was a preference or an affectation of the publicity-hungry general. Whatever the case, there is no question Crook carried the concept of the mule train to its greatest refinement in the Old West.

Much of the credit for Crook’s success goes to his chief packer, Thomas Moore, whom he first contracted when organizing expeditions against the Apaches in 1871. Moore’s services proved so valuable that Crook later summoned him to Wyoming to organize pack trains for his 1876–77 expeditions against the Lakotas and Cheyennes, as well as for hunting and fishing trips with select dignitaries. Moore was born in St. Louis in 1832 and migrated to California in 1850. From there, he drifted up to Idaho, where he prospected for a while and may have driven a stagecoach. Ironically, considering the muleteers’ reputation for hard drinking and hard living, Moore was the brother of temperance fanatic Carry Nation, notorious throughout the country for smashing saloons with her hatchet.

It was Tom Moore who perfected the ancient Spanish-Moorish aparejo for use by the U.S. Army. Still used in the Middle East, Spain and Mexico, this packsaddle consists of two leather pads stiffened at the front and rear by hardwood sticks and stuffed with straw. Joined at the top by a gusset, the pads hang down either side of a mule, spreading the load evenly across its back and sides. Crook’s aide, Lieutenant John Gregory Bourke, described the method: “First, the mule must be blindfolded with tapojo [blinders], then the suedero, or sweat cloth, is placed upon the withers, followed by two saddle blankets and the sobrejaluca, which supports the aparejo, made of stout canvass, faced with leather….This is made to double in the middle of its length and secured to the animal by a cincha, or belt of canvass, passing around the girth. Covering the aparejo comes the corona, a gorgeously ornamented covering of frieze or blanket, often wrought with odd and fantastic designs cut out of scarlet or azure cloth. Finally comes the cargo, as the pack is technically called, securely held in its place by two ropes[:] the reatas and the lasso, worked into a peculiar knot called the diamond hitch. The animal’s eyes are now freed, and altho’ it may display a desire to extricate itself from its burden, it soon learns to comport itself as a well-bred pack mule.”

Not every military expedition organized its mule trains as efficiently. During the famous 1876 Lakota-Cheyenne campaign, Brig. Gen. Alfred Terry’s Dakota Column packers were incompetent, their mules untrained, and the expedition had trouble from the outset. When the column linked with Crook’s in southern Montana Territory, in the wake of the disaster at the Little Bighorn, Bourke called Terry’s pack train “a burlesque, formed of mules freshly taken from harness and superintended by soldiers who approached their new duties with ill-concealed indifference or reluctance.” He added: “On this first day’s march, and a very short and comparatively easy march it was, Terry’s pack train dropped, lost or damaged more stores than Crook’s command had spoiled from the same causes since the campaign commenced [six weeks earlier].”

The amateurishness of Terry’s men already had told a few weeks earlier at the Little Bighorn. From the time Lt. Col. George Custer had separated from Terry, two days before the fight, the cantankerous mules had given trouble. On the day of battle itself, the pack train lagged behind. Captain Frederick Benteen’s battalion, which had been sent to scout the upper part of the Little Bighorn Valley, was returning to the command with orders to bring up the packs when it encountered the mules just coming up the trail. “Many of them had been poorly packed, and they had sore backs and were pretty tired,” Sergeant Charles Windolph recalled. They also had gone about 24 hours without water and, arriving at a damp morass, broke loose and became mired in the boggy ground. Benteen pushed on, leaving the mules to catch up as best they could. Eventually, the pack train joined Benteen and Major Marcus Reno, who were pinned down on a hill several miles from where Indians were annihilating Custer and five companies. It is doubtful a better-organized mule train would have altered the outcome. Nevertheless, it demonstrates the problems posed by inexperienced packers and untrained mules.

Sometimes the government, concerned with the cost of transporting wagons to a destination where vehicles were scarce and mules plentiful, would order four-mule teams to pull six-mule wagons. While this may have been cost-effective mode of transit, the mules suffered. Contractor Lowe said that pulling such a heavy load “jerks the leaders painfully and gives them sore shoulders. Six mules can haul 2,500 pounds with less injury to them than four mules can haul the empty wagon.”

Ultimately, however, the mule gave way to technology. The completion of the transcontinental railroad at Promontory Summit, Utah, on May 10, 1869, marked the beginning of the end. Mules continued to serve in out-of-the way places until the early 20th century, by which time steam or internal combustion rendered it obsolete. Locomotives and gasoline-powered vehicles handled surface needs, while electric motors and compressed-air engines moved ore and equipment in the mines. The plow mule lingered the longest—well into the 20th century— until he, too, was finally put out to pasture, by the tractor.

If the mule is a relic of the past, however, its achievements remain wherever one looks. Its greatest monument is the modern American West.

Texas teacher Charles M. Robinson III is the author of many articles and several Western history books. His General Crook and the Western Frontier is recommended for further reading, along with Sharps Rifles and Spanish Mules, by Wayne R. Austerman, and The Prairie Traveler, by Randolph Barnes Marcy.

Originally published in the February 2009 issue of Wild West. To subscribe, click here.