It was 1900 and the city of Paris greeted the twentieth century with the Exposition Universelle, a world’s fair to celebrate the arts and sciences of the past century and to anticipate the wonders of the next.

Among the many diversions available to visitors was the opportunity to go aloft in a balloon. A photograph taken of one such group of amateur aeronauts shows a group of men in hats and high collars, looking very serious—all except one. This man, Hugh de Laussat Willoughby, stands slightly apart from the others, unable to contain a smile; it radiates from his crinkled eyes, as if going up in a balloon is the greatest lark of his life. For him, that would be saying quite a lot.

From Silver Spoon to Flying Goggles

Willoughby was born in 1856 to a well-to-do family in Middleton, New York. He studied mining engineering at the University of Pennsylvania but never worked in that field. Independently wealthy, he put his time and money into things that interested him. These included yachting, motorboats, bicycles and aviation. He declared ballooning to be “the king of sports,” but balloons would eventually lose the crown to airplanes.

In 1897 Willoughby made a name for himself as an explorer. He undertook an expedition to sail around the southern tip of Florida through poorly charted waters and little-known islands. He and a guide then took to canoes and crossed back to Miami through the Everglades. In doing so, he became the first non-native to cross this region, though he acknowledged in Across the Everglades, his memoir of the journey, that the Seminole Indians had been doing it for a long time. Although Willoughby gained considerable respect for the Seminoles during his time in the Everglades, they had never mapped the region. Willoughby did, employing the inventiveness that he would later use in his flying machines. Since he made his journey through the Everglades entirely by water flowing through tall grass, he could use neither a surveyor’s wheel nor a ship’s log to measure the distances. Instead, he fitted a bicycle wheel with paddles, connected it to an odometer, and attached it to his canoe. The wheel turned as the boat moved through the water, measuring each day’s travel.

Satisfying though that achievement may have been, however, Willoughby realized that unknown lands were becoming ever fewer as the twentieth century approached; new technology was becoming the new frontier.

Enter the Brothers From Ohio

In 1899, Wilbur and Orville Wright began to study seriously the problem of powered flight. The Wright brothers succeeded in flying an airplane in 1903, but they did not give any public demonstrations until 1908. Orville put the Wright Flyer through its paces at Fort Myer, Virginia, hoping to get a contract with the United States Army for flying machines. Meanwhile, his brother Wilbur was in Paris, sounding out the French government as a potential customer.

To clinch the deal with the Army, Orville had to demonstrate that the Wright Flyer could meet a set of rigorous requirements. The demonstrations went on for two weeks. It’s likely that Willoughby had started corresponding with the Wrights by this time, for he traveled to Fort Myer and assisted with the demonstrations, while also seeking to discuss his own ideas with Orville. No doubt he made careful observations of the airplane while he was there.

Orville’s demonstrations came to an abrupt and tragic end on September 17, 1908. To demonstrate the Flyer’s passenger-carrying capabilities, Orville took an Army observer, Lieutenant Thomas E. Selfridge, aloft with him. One of the wooden propellors broke during the flight and the airplane became uncontrollable. The resulting wreck killed Selfridge, giving him the unenviable distinction of becoming the first person to die in the crash of a powered aircraft.

Colleagues in the air

Orville Wright was seriously injured in the accident, but during his recuperation he and Willoughby corresponded. It is clear from the letters that Willoughby was already planning to build his own airplane. His letters to Orville included questions about flying among inquiries about Wright’s improving health. In one of his replies Orville wrote, “I don’t want you to go to any considerable expense in your experiments, for as I told you at Washington, I could only give permission to use our invention till we have some of the machines built and for sale.” That seems friendly enough, but it could be also taken as a warning not to infringe on any of the Wright brothers’ patents.

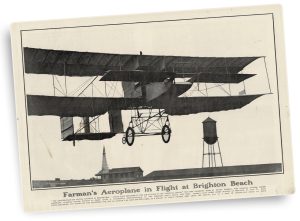

Orville did not need to worry about Willoughby’s expenses; he could afford them. A common quip among modern-day private pilots goes, “If God had intended man to fly, He would have given him more money.” If this is indeed the case, then God intended Hugh Willoughby to fly. But he was not interested in buying a Wright machine. He wanted to build one himself and before long was patenting inventions of his own. Chief among these was what Willoughby called his “double rudders,” although the 1909 patent (U. S. Patent No. 1,008,096) is simply titled “Airship.” According to the description, the invention was suitable for “aeronautical machines of all types, but particularly adapted to that class known as aeroplanes.” It was an arrangement of fore-and-aft elevators (“horizontal rudders” in the terminology of the day) that allowed more responsive pitch control. The two elevators moved in inverse directions, so that as the forward “rudder” drove the nose up, the one in the rear pushed the tail down and vice versa. The Wright brothers and Anglo-French aviation pioneer Henri Farman incorporated this innovation into some of their machines, but the first aircraft to use it was Willoughby’s War Hawk.

Despite the name, Willoughby never intended the War Hawk for military use. He named his airplane after the frigate bird, or man-o’-war hawk, that he had seen in Florida. Besides having Willoughby’s double rudders, the War Hawk was a remarkable airplane in many other respects. With a wingspan of 44 feet, it was the largest airplane in the world in 1909. Furthermore, it was the first tractor biplane on record; that is, the propellor was at the front of the airplane and pulled it through the air, rather than pushing it from behind as other biplane designs of the time did. (In France, Louis Blériot was developing tractor monoplanes.) Willoughby was convinced that this was a superior configuration for aerodynamics, but also considered it a safety feature. In a crash, the pilot would come down on top of the engine, rather than the engine on top of the pilot. The engine power was controlled by a unique device that Willoughby would also patent as an “aeroplane engine controlling mechanism” (U. S. Patent No. 1,024,303). This was a foot pedal that, unlike the accelerator of an automobile, reduced the power as the pilot depressed it. Depressing the pedal all the way would shut off the engine, a feature that Willoughby touted as another safety device. Willoughby also took ideas from other sources to create a unique system of controls. For roll control, the War Hawk used the Wright brothers’ system of wing warping, operated with a shoulder harness developed by Glenn Curtiss. There were control wheels at the sides of the cockpit for pitch and yaw.

Willoughby worked on his airplane for more than a year in Ventnor, New Jersey. It must have been quite a sight, for he coated it with paint made, he said, from “pure banana oil and ground aluminum.” By September of 1910, Willoughby got the War Hawk into the air. Contemporary accounts are not specific about how high, how fast or how far the War Hawk flew, noting only that it did. For an airplane the size of the War Hawk in 1910, that was achievement enough.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

The next challenge

The following year, Willoughby was ready to move on to his next project. At his winter home on Sewall’s Point in Florida, he began work on a “hydro-aeroplane,” or seaplane. French aviator Henri Fabre flew the first successful “hydravion” on March 24, 1910, but Glenn Curtiss, Gabriel Voisin and Hugh Willoughby were not far behind. Willoughby named his new machine the Pelican, claiming that, when diving, the namesake bird moved its head and tail in the same manner as his double rudders operated. While Curtiss and the Wrights would build hydro-aeroplanes on a flying boat design, Willoughby built the Pelican with a pair of pontoon floats under the wings, a configuration that remains a standard on modern seaplanes. Like the War Hawk, the Pelican was a tractor biplane with Willoughby’s patented double rudders and engine control. He built the parts at Sewall’s Point and then tested the machine at his summer home in Newport, Rhode Island. Although Willoughby proclaimed satisfaction with the tests, the Pelican was underpowered, with its engine producing only 30 horsepower.

Upon bringing the floatplane back to Florida, Willoughby developed another innovation to help with water takeoffs. This was the Pelican Nurse, a catamaran motorboat with each of its twin hulls outfitted to hold one of the Pelican’s floats. With the Pelican mounted on the Nurse’s nose and both the boat and airplane engines running at full throttle, the pair would roar across the water until reaching takeoff speed, when the airplane would be released and take to the air. That, at least, was the concept, but Willoughby eventually discarded that cumbersome plan in favor of adding a 50-horsepower engine that improved the Pelican’s performance.

Air travel for the upper-Class Sportsman

Some things seem inevitable in the history of flight: air mail, passenger travel, the armed might of an air force. But aviation pioneers conceived of many uses for the airplane. Some came to pass and some did not. With the success of his Pelican, Willoughby developed his own vision for the hydro-aeroplane based around his interests as a wealthy sportsman, an avid yachtsman and a motorboat enthusiast. Prior to the First World War, Willoughby viewed aviation primarily as a sport and he believed the hydro-aeroplane was the ultimate sports machine. With that in mind, he formed the Willoughby Aeroplane Company at Sewall’s Point and set out to build seaplanes for other wealthy sportsmen.

Willoughby hoped to persuade potential buyers by emphasizing the safety of the hydro-aeroplane, especially when flown at low altitude over water. “There is no longer any excuse for flying over cities or mountainous countries where the stopping of an engine means death,” he wrote in 1912, adding “the safe touring in the future will be done by the hydro-aeroplane, using it as a motorboat on the surface of the water…and as a flying machine attaining the wonderful speed of the aeroplane.”

Willoughby put his proposition to the test several years later. On June 18, 1918, the Coast Guard life-saving station at Gilbert’s Bar, near Sewall’s Point, reported a “most unusual rescue.” Willoughby was flying a Curtiss flying boat when he had to ditch in the Indian River near the station. The surfmen, spotting the crippled aircraft, helped Willoughby get to shore. He was not injured but rough waves damaged the wing and hull of the Curtiss as it washed ashore. The Coast Guard report states that the aviator’s primary concern was to salvage the engine.

Aviator emeritus

At that time Hugh L. Willoughby, at age 61, was America’s oldest pilot, a status he retained until his death in 1939. He did not see his patented double rudders, of which he was so proud, become a standard of aircraft design, although some early models of Wright, Curtiss and Farman biplanes did use them. However, the tractor biplane, of which the War Hawk was a pioneering example, did prove to be an enduring design, from the combat aircraft of World War I to the aerobatic biplanes that thrill modern airshow crowds.

Today the Historical Society of Martin County, Florida, is the parent organization of two museums that commemorate Willoughby’s remarkable career. The Elliott Museum in Stuart, Florida, boasts a replica of the Pelican, along with other mementos from Willoughby’s time as an aviator and explorer. The society also operates the Gilbert’s Bar House of Refuge Museum, where Willoughby and his engine were rescued by the Coast Guard. Hugh Willoughby would be proud of his legacy.

David Boehnlein is a retired high energy physicist who occasionally transformed aviation fuel into noise with a Cessna 150. He now resides in Hampton, Virginia, where he is a freelance writer, master naturalist and a volunteer docent at the Virginia Living Museum’s Abbitt Observatory. For additional reading, he recommends Across the Everglades by Hugh Willoughby.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.