The UH-1 “Huey” helicopter, one of the most recognizable symbols of the Vietnam War, continues to stir memories more than 60 years after American troops first heard the old workhorse’s distinctive whop, whop, whop as it approached for air support, the insertion of reinforcements, mail delivery or medical evacuation.

“It can be a love-hate relationship,” said Huey pilot Phil Marshall, who was a 21-year-old warrant officer with the 237th Medical Detachment and continues to fly the chopper as a volunteer with a nonprofit organization founded to rehabilitate old Hueys and build a museum in Peru, Indiana. “The sound is something you will never forget. It can bring back good and bad memories, so it can be traumatic.”

Marshall was shot in the arm during a night mission extracting three seriously wounded soldiers. That incident sent him home, but it didn’t end his love affair with the aircraft.

The feelings many veterans have about the Huey are “not something you can explain,” said Melvyn “Mel” Lutgring. “It just becomes a part of you.”

Lutgring, a Louisiana native who served with the 174th Assault Helicopter Company at Chu Lai in northern South Vietnam from June to November 1971, said that special attachment might have something to do with the bonds that men forged on the battlefield.

“You can’t buy that kind of brotherhood for any amount of money in the world,” he said. “The Huey brings that all back.”

Lutgring loved being a crew chief on the machine, praised for its light construction, high maneuverability and reliability.

“You could get it flying again with duct tape and bailer twine if you had to,” he said.

Jim Watkins, a maintenance specialist on a Huey hit by .51-caliber anti-aircraft fire that took out the engine, said the bird could be completely incapacitated and still land without crashing. Shot down in Laos, he and the rest of the crew spent two harrowing nights and three nerve-wracking days surrounded by the enemy, but they all got out alive — after being rescued by another Huey.

“I can recall just one major problem while flying — a hydraulics failure,” Marshall recalled. “And that was with more than 1,000 hours flying time. It is an incredibly reliable machine.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Bringing Peace

Now in retirement, Marshall has gathered enough stories from Vietnam veterans to fill more than a dozen books about daring helicopter missions. Some of the stories come from veterans he met while doing volunteer work with American Huey 369 Inc., a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit charitable organization formed in 2005 to restore Hueys and build The National American Huey History Museum. When completed, the museum will offer a comprehensive history of the Vietnam War’s iconic helicopter while serving as a place for education and remembrance.

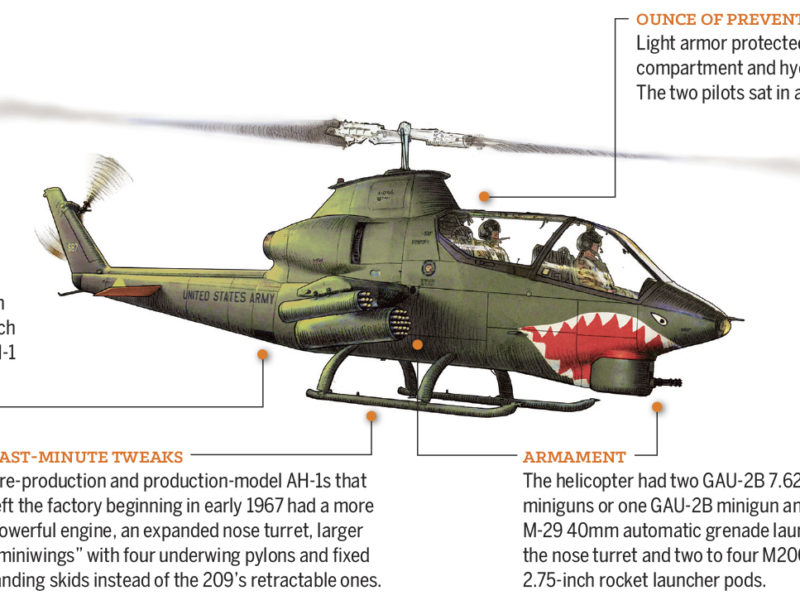

American Huey 369 has four Hueys that are in the air again. In the fall of 2021, the organization brought home its 15th aircraft, an AH-1 Cobra with an impressive combat history that will be used as a static display. Some of the Hueys are taken to events for the public to see, touch and even fly in if they become members of the organization.

Marshall noted that at every event the volunteer crew comes across at least one veteran who is affected by his reunion with a Huey. “We want to help him and bring him home,” he said. “Bring him peace. That’s what it’s all about.”

Veterans who may have not yet come to terms with their time in Vietnam are not hard to spot, Marshall said.

“They are usually standing by themselves in the distance staring at the Huey. Maybe their arms are crossed. We go out and talk to them and invite them to come closer—even take a ride. It’s a healing experience. Hueys can have a powerful impact.”

The interaction with the public has the added benefit of teaching younger generations about the war, the sacrifices of the veterans who served and the important role of the Huey.

Recommended for you

The Huey’s Iconic Status

Although many other aircraft played their parts in the Vietnam War, the Huey is likely the most recognizable and memorable. Almost every soldier experienced or benefited from the Huey in one of its myriad roles—delivering beans, bullets, water, mail, troops, the wounded and firepower.

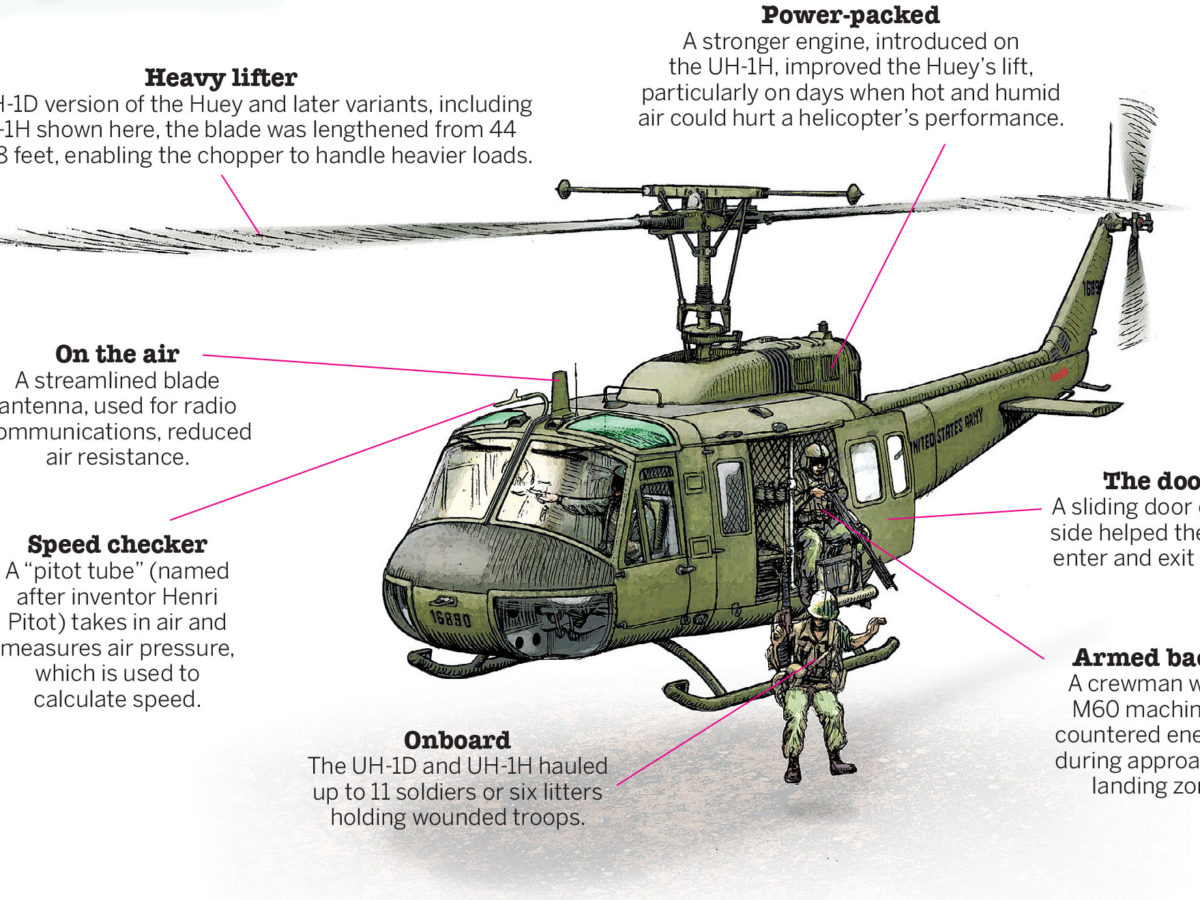

The first helicopters that became known as Hueys entered service in 1959. Bell Helicopter Co. designated the aircraft the HU-1 Iroquois, and GIs dubbed it “Huey.” The designation changed to UH-1 in 1962, but the troops kept their name for the helicopter. The first Hueys in Vietnam arrived in April 1962 as medevac helicopters.

As new variations of the Huey were put into service, they were identified in the field by nicknames. Choppers used for medical evacuation came to be known as “Dustoffs.” Huey medevacs were able to get the wounded from the battlefield to the hospital faster than the transport planes used in World War II and early helicopters of the Korean War. That speed, coupled with advancements in medical care, meant a much better chance of survival. A soldier seriously wounded in World War II had a 40 percent chance of survival. With the Huey and onboard medics, the survival rate jumped to 98 percent because the wounded could be in a medical facility within an hour or less.

Huey gunships had a nomenclature based on their armament. “Frogs” carried grenade launchers on the helicopter’s nose. “Hogs” or “heavies” carried large rocket pods. “Guns” or “lights” were fitted with various configurations of the fuselage and pod-mounted machine guns, miniguns and smaller rocket launchers.

The version of the Huey used to transport troops and supplies was referred to as a “slick” because it only had door guns, no external weapons mounted on its sides, resulting in a fuselage with a smooth, “slick,” surface.

Back to the Skies

Only about a dozen privately owned Vietnam-era Hueys are flying in their original military configuration. Three—a Dustoff, a slick and a gunship—are in the air thanks to American Huey 369.

The organization’s president, former Marine Capt. John Walker, who was a pilot on Sikorsky CH-53 King Stallion cargo helicopters, purchased Dustoff Huey 369 in December 2004 from an eBay listing. He traveled 1,300 miles to Maine with his brother Alan to check out the chopper in January 2005.

Advertised as “mostly complete and not flyable,” the $40,000 helicopter lay on the flight line at an airport in Bangor, Maine, open to the elements. The transmission was rusted solid. Walker was OK with its condition because he had no desire to put Huey 369 back in the air, but that changed with the donation of a slick, Huey 803, and parts of another Huey in September 2005. Walker decided to restore the slick as a static display to raise money for the complete restoration of Dustoff 369 so the helicopter could fly again.

Huey 803 was considered too far gone to make airworthy again, but it had a rich history in Vietnam, serving initially as a medevac in the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile). The helicopter participated in the November 1965 Battle of Ia Drang in the Central Highlands, the first time battalion-sized units of the U.S. Army and North Vietnamese Army fought each other. Later Huey 803 was transferred to the 336th Assault Helicopter Company with a new job and identity, Warrior 11. The Huey lost its skids during a hard landing in 1968 but hobbled back to Soc Trang in the Mekong Delta and landed on sandbags.

In mid-2007, Huey 369 returned to the sky. The American Huey group held a reunion in August 2007 for volunteers and veterans so they could watch it fly again. As planned, Huey 803 was put on static display. It had already been viewed by thousands of people at events that year, providing them with the unique experience of seeing, touching and sitting inside a historic aircraft.

During the reunion, Richard Bowie, a director of an emergency medical organization, donated a Huey turbine engine with the stipulation that it be used to fully restore Huey 803. The core members of American Huey 369 went back to work, and in July 2009 Huey 803 was in the air.

A Painstaking Restoration

The organization’s most recent and perhaps most remarkable restoration is gunship 049. Considered to be the most historically significant Huey to have outlasted war and returned to flight status, Huey 049 defied all odds by surviving six years in a battle zone and accumulating 3,468 combat hours. Those figures are incredible considering that half of the 7,000 or so Hueys that served in Vietnam were lost in battle. Statistically, the life expectancy of a Huey during the war was three to six months.

Like the Huey 803 helicopter, Huey 049’s extraordinary background includes participation in the Battle of Ia Drang. It provided cover fire at Ia Drang’s Landing Zone X-Ray as Hueys came in and out of the LZ. The gunship was involved in constant combat from 1965 to 1971, before continuing service in various units of the Army National Guard back in the States. Similar to the neglected Huey 369, the 049 chopper was in 2 feet of snow when Walker first saw it in Minnesota. Despite the helicopter’s lack of rotors and head, he thought Huey 049 was worth saving and hauled it back to American Huey’s Indiana hangar in June 2011.

Before work began on this new acquisition, a complete XM-21gun system came on the market—a rare occurrence today. The price was $55,000. Considering that the organization had already restored two Hueys in four years without a single cash donation exceeding $1,000, the purchase of this one-of-a-kind gun package seemed out of reach. “It might as well have been $5.5 million,” Walker said.

Huey 369, the initial purchase, had been restored with no large benefactors and no state or federal funds. The American Huey members relied solely on donations. “Rather than ask directly for money, I like to tell people who we are, what we are doing and what we plan to do,” Walker said. “We want people to give because they see the value in the Huey’s healing ability for our veterans and the importance of preserving their history.”

Walker, along with brother Alan, co-founder of the organization, his wife Kae and 17 core members, raised the needed money to buy the gun system, which was put into storage at the organization’s hangar. In November 2011 about 45 volunteers gathered to bring Huey 049 back to life. With the gun pack as an added incentive, the volunteers were eager to take on this new project. “Honoring the fallen is an amazing motivator in the restoration of a historic aircraft,” Walker said. “It is the fuel that keeps American Huey 369 forging ahead.”

However, he soon received bad news. After the head inspector, Dick Hosmer, examined Huey 049, he pulled Walker aside and told him it would not be financially feasible to make the helicopter fly again. Two decades of neglect and decay—not to mention the abuse of serving in battle—had left the gunship with too much damage to consider a full restoration.

“A Lifesaver”

Walker did not let that diagnosis stop him. Huey 049’s rich history was just one of the reasons Walker launched his mission to restore it. Another motivation was the large number of veterans connected to that particular Huey. During its six years in Vietnam, 049 had come in contact with a countless number of soldiers. From pilots to gunners and crew chiefs, thousands of lives had been touched by that historic warbird in some way.

“The aircraft needed to be finished because so many veterans who were connected to it, directly and indirectly, are still alive,” Walker said. He wanted to give them the opportunity to sit—and even fly—in 049 again.

“You have to understand, to these guys the Huey was a lifesaver they trusted to get them home,” Walker said. “When I’m speaking about the true value of these Hueys, I always stress these aircraft are for all the guys who didn’t come home and for those who did and remember the Huey as an angel that extracted them from hell.”

After six years and lots of help from Vertical Lift Components in Texas, the 900-page work order was completed. More than 70 battle scars from bullets and shrapnel were discovered during the restoration process. Vietnam campaign ribbons now mark the location of the Huey’s war wounds. Huey 049 went through its first hover checks in January 2017 and is now flown to events along with the other restored Hueys.

The cost in both time and money are almost unfathomable, but Walker said the restoration was worth it. “Being able to reunite so many men with the exact airframe that they served in combat with is a priceless experience,” he said.

Walker and his crew did not cut any corners in the restoration. The guns are authentic, including rocket pods, miniguns, sighting systems, ammo cans and feeding systems. The instrumentation in the cockpit is completely faithful to 1964, and even the radios are original military radios. The only modern avionics aboard the chopper are the transponders.

The organization has fourth soon-to-be airworthy Huey, donated by Lockheed Martin Corp. Although not in its original wartime configuration, Huey 959 is in pristine condition and gives the museum another 1st Cav aircraft whose history includes the Battle of Ia Drang, where it served with Company A, 227th Aviation Battalion.

Walker considers the three Hueys involved in the Battle of Ia Drang a priceless treasure. “All the billionaires in the world couldn’t purchase three airworthy helicopters from that one battle,” he said.

American Huey 369 has given more than 23,000 membership flights to people who attend its events and join the organization for a $100 fee. Members also get a photo taken in front of the Huey after their flight and receive personalized dog tags that come a few weeks later.

The Museum project

A groundbreaking for the museum was held on Aug. 14, 2021. The 34,000-square-foot structure is being built east of the Grissom Air Reserve Base outside of Peru. Supported by donations, memberships and grants (but no state or federal funds or loans), American Huey 369 is more than halfway toward its $4 million goal for completion of the museum.

Much of the money was raised through Founder’s Gifts of $1,000. The names of those donors will be engraved on a 7-foot-tall bronze plaque, and information about them will be available in a kiosk in the museum’s entryway. Honorary bricks that will be incorporated into a Memorial Pathway can be purchased to help support the museum.

The bricks, $100 apiece, can be inscribed with the name of a loved one, a business or a veteran. American Huey 369 also hopes to display bricks honoring the more than 58,000 service members listed on “the Wall” in Washington.

In addition to raising funds for the museum, the nonprofit wants to create a rainy day account that will be used for the future and to provide scholarships for Gold Star children, the survivors of service members killed in war.

An opening date for the museum has not been set yet, but construction is underway.

Even though the Huey’s reputation was earned in the gunfire of the Vietnam War, that conflict was not the only battlefield where the Huey gained acclaim. Hueys have operated in Grenada, Operation Desert Storm, Bosnia, Iraq and Afghanistan.

The Huey’s ongoing Legacy

The Huey is generally associated with the Army, but its variants have been used by the Navy, Air Force and Marines, a testament to the aircraft’s capabilities and versatilities. The Army retired its last Huey on Dec. 16, 2016, but the Huey is still being built for the Marines and foreign governments at a cost of $30 million each.

The Huey’s military exploits are not the helicopter’s only honors. The Huey rescued residents off rooftops after Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast in August 2005 and continues to save lives during national disasters. It is also used by law enforcement, hospitals, media outlets, and search and rescue operations.

With its wartime legacy and the crucial roles the helicopter still fills today, it’s not hard to understand why the sight—and sound—of a Huey still attracts attention. While merely an interesting machine to some, the Huey is a warrior, a lifesaver, an angel and most of all, a dear old friend, who continues to have an emotional tug on the veterans who know it best.

Jessica James is a freelance writer and award-winning author who lives in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

This article appeared in the June 2022 issue of Vietnam magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.