Orville Wright never lost his capacity for finding inspiration in playthings

Though profoundly shy, Orville was the “fun” Wright brother—fond of jokes and pranks and given to tinkering with toys, two of which bookmarked the younger Wright’s career. The first plaything sparked his and Wilbur’s fascination with heavier-than-air flight, the other brought Orville, late in the arc of his journey, into a new chapter of a multifarious life.

The Wrights’ odyssey into aviation began with a toy helicopter. The miniature contraption, which was fashioned of wood and paper, got its power from a twisted rubber band that drove a propeller. French aviation pioneer Alphonse Penaud had invented this gizmo in 1870, extrapolating on a version called the “Chinese top” made in 1796 by Englishman George Cayley. Cayley’s device used a whalebone spring to spin a feathery propeller whose rotations carried the device aloft. A serious experimenter, Cayley wrote of aviation in detailed letters that laid the foundations for later scientific inquiries. Cayley’s work was well known to any flying enthusiast, whether Penaud or Wilbur Wright.

“Helicopter,” from the Greek helix, meaning whirl or spiral, had been coined in 1861 by archaeologist Gustave Ponton d’Amécourt. He made up the word to describe a steam-powered flying machine he built and unsuccessfully tested that year. Also that year Confederate inventor William C. Powers, seeking a way to attack Union warships that were blockading Southern ports, drew upon drawings by Leonardo Da Vinci to conceive a similar aeronautical mechanism that never flew.

In 1870, during the Franco-Prussian War, the Prussian army besieged Paris, Penaud’s hometown. Bored and laid low by a bone disease, the 24-year-old distracted himself by improving on Cayley’s plaything, substituting rubber bands for bone. Friends and acquaintances enjoyed watching the propeller hoist his toy-like contraption skyward. When peace returned, Penaud continued to fiddle with miniature flying machines. At the Gardens of the Tuileries in central Paris, he demonstrated a rubber band-powered “planophore.” The unit had two bat-like wings with a span measuring 20 inches, a long, narrow body, and a vertical stabilizer. A propeller’s spoon-shaped blades pushed the mechanism aloft. Members of the Société Aéronautique watched the thing rise and circle to a gentle landing—the first self-powered flying machine resembling what became the airplane. Penaud, who credited his yen for aviation with mitigating his bone condition, undertook a series of unsuccessful flying projects with beautiful and imaginative designs. In 1876 he took his own life.

Penaud’s miniature helicopter design survived him, crossing the Atlantic to be marketed as a children’s toy. In 1878 Milton Wright, a circuit-riding bishop of the United Brethren, a Protestant sect, bought one of these toys while traveling among congregations in Ohio. Milton and wife Susan lived in Dayton. They had five children; their youngest sons were Orville, seven, and Wilbur, 11. Arriving home for one of his brief stays, Milton summoned Orville and Wilbur and told his sons to watch. He tossed a Penaud helicopter their way. The toy rose to the room’s ceiling, hovered, and descended. Fascinated, Wilbur and Orville tried to build larger versions. This first collaboration started a partnership that matured and deepened. Among the brothers’ first discoveries was that any increase in size hampered the task of getting the model to fly. In time the Wrights’ wind tunnel research showed to that if a flying machine’s weight doubled, its motive power had to increase by a factor of eight to keep the machine aloft.

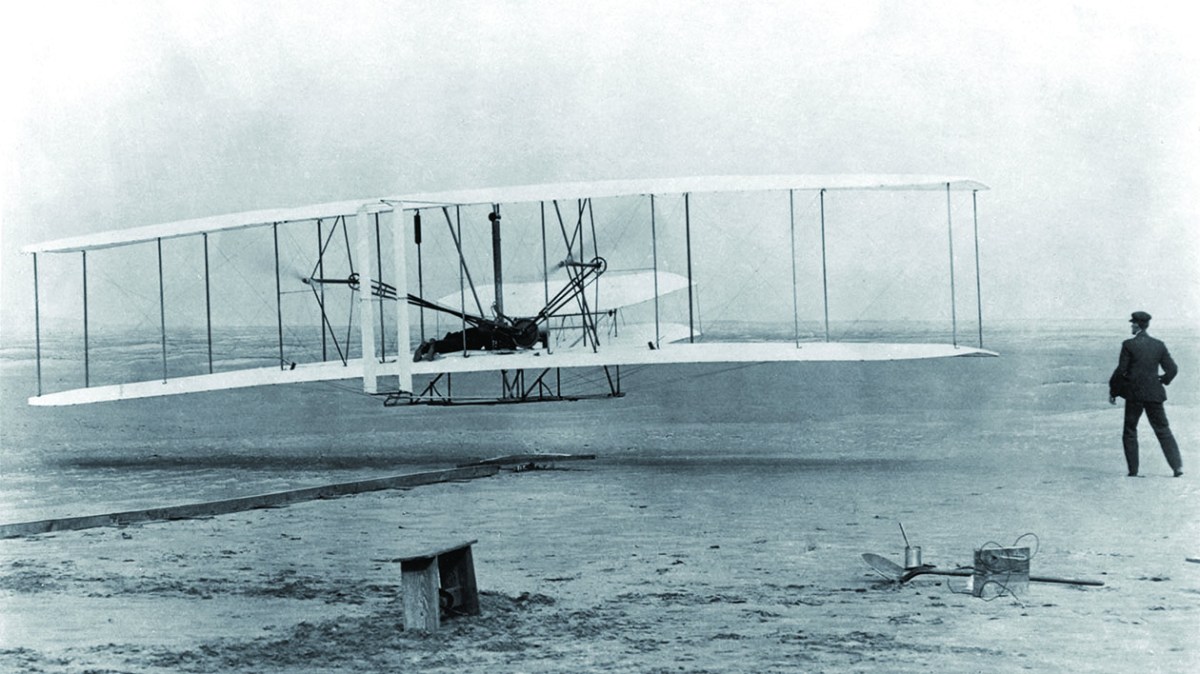

This reality, which had vexed Penaud and other would-be aviators, drove the Wrights to keep tinkering until, at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, in 1903, they got their wood-and-fabric biplane Wright Flyer aloft, pushed by a propeller connected to a 12-horsepower four-cylinder water-cooled internal combustion engine with an aluminum crankcase. Orville, who had won a coin toss, was at the controls. Press coverage enveloped the brothers, who explained that a toy had set them on their path. Both Wrights described Penaud’s helicopter as a “bat”—Orville doing so when being deposed for a patent lawsuit. The Penaud helicopter became known as the “Wright Bat,” and as such is still being sold.

Wilbur and Orville Wright were anything but alike. Wilbur was the deep thinker, the eager public speaker with the inner drive and intellectual focus to make manned flight happen—an eventuality his brother would have been unlikely to achieve on his own. Instead, Orville was an inveterate tinkerer, always ready to grab a pair of pliers and apply them inventively.

Success at flying and then at selling airplanes brought the brothers fame and no small fortune—Orville built a large house in Dayton called Hawthorn Hill where he lived with their sister, Katherine—but also woes in the form of imitators and frauds they pursued in court at much cost to Wilbur’s health. He contracted typhoid and in 1912 died. Orville ran Wright Aeroplane Company, working with chief mechanic James Jacobs to invent the split-flap, which improved control during dives—a key factor for dive-bomber pilots during World War II. By the 1920s Orville had sold most of his aviation holdings, forsaking commerce for research, a path to which he hewed until his death in 1947. He worked closely with NASA’s ancestor, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. He had a hand in designing civilian and military aircraft, created automatic aircraft stabilization systems, worked with Chrysler on streamlining automobiles, helped with wartime code-breaking, and more.

Without his brother and their epic quest to focus his tinkering, though, Orville came to concentrate on making things that made life easier and entertained him. He added a Lazy Susan to a dining room table. To haul provisions from the icehouse, he constructed a miniature railroad powered by a repurposed outboard motor. To cool his head and ward off insects he perforated the crown of a felt hat, covering the holes with mosquito netting. He made a toaster that worked on his oil-fired kitchen stove. A chronic practical joker, he had an artisan make two identical small wooden chests configured so he could swap their contents unseen, befuddling victims. He was fixing the front doorbell when a heart attack killed him at 80.

But before that, a second toy changed Orville Wright’s life. Among nieces and nephews who often visited Hawthorn Hill was Ivonette Miller, the married daughter of his older brother Lorin. Ivonette was there at Christmas 1923 when Orville demonstrated a toy he had made, based on one he had played with as a boy. “It was a contraption with a narrow base board about 18 inches long,” Ivonette wrote later. On one end was a springboard fitted with a seat holding a little wooden clown with wire hooks for arms. “On the other end of the base was a revolving double trapeze with a counter balancing clown holding to the bottom side,” Ivonette wrote. “When a similar clown was released from the springboard, it flew through the air and caught the top side of the trapeze to revolve.”

The mechanism delighted all onlookers. Ivonette’s husband, Harold S. Miller, recently had become co-owner of a toy company, Miami Wood Specialties. Miller was always looking for new lines to enhance his company’s inventory. His wife’s famous uncle’s gizmo appealed to Miller, and he asked Orville’s permission for Miami Wood Specialties to market it. Orville agreed, and spent hours making the figure drawings needed to manufacture “Flips and Flops, the Flying Clowns,” which he submitted to the U.S. Patent Office. On January 25, 1925, the government duly granted Orville Wright Patent No. 1,523,989—his sixth and final patent, which he assigned to Miami Wood Specialties.

Production started small; clown figurine blanks originally were brought home for the Wright women, including Ivonette, to paint, but soon production had scaled up. Miami Wood may have licensed the toy to other manufacturers; Dutch Novelty Shop of Holland, Michigan, marketed a nearly identical toy, “Flying Clowns,” which carried the same patent number.

Priced at $7.80—today, $115—Flips and Flops initially flopped, and not in a good way. For his prototype, Orville had used a wooden slat as a springboard. Miami Wood did the same in mass production but found that wet weather warped the wooden part, disabling the first 10,000 units. A steel springboard solved the problem, leading the toy to gain such popularity that Miami Wood began having trouble meeting demand. As an infusion of capital, Lorin Wright bought into the company, made back his investment in six months, and bought out his son-in-law’s partner. Lorin Wright signed the company over to Harold Miller and his brother Horace.

The clan was now in the wooden novelties trade, with Uncle Orville an active participant. According to Ivonette in her memoir, Wright Reminiscences, after millions of sales, Flips and Flops lost momentum, though records for Miami Wood’s successor company show the product on sale as late as 1946. Decades later Ivonette, told by an interviewer that his personal Flips and Flops was short a clown, rummaged through her bedroom and found a spare that she gave him.

To counter waning Flips and Flops sales, the family got into balsa wood airplanes, both as individual retail items and for sale in bulk to clients who had the planes printed with company and product names. Orville designed a machine capable of printing on balsa. Miami Wood put it to work. Some toy planes bore the origin mark “Wright, Dayton.” Most resembled today’s simple balsa planes, but some were quite complex. The slingshot-launched “Wright Seaplane,” a biplane design, had an adjustable tail and cost fifty cents. On its fuselage, the Seaplane wore a small drawing of a Wright Flyer.

Several sources claim Orville helped design the balsa planes, but no source confirms this. However, James Jacobs, who as chief mechanic at Wright Aeroplane Co. had helped Orville Wright invent the split-flap—and later went to work at Miami Wood Specialties—obtained patents for five toy gliders on which Miami Wood based its designs.

One of Jacob’s best designs was the Autogiro, which, like other toy flying machines, had a shaped balsa fuselage. However, the narrow wings were attached with hinges and were mounted vertically rather than horizontally, as most aircraft wings were mounted. This allowed the Autogiro’s wings to fold flat against the fuselage. Aimed straight up by a slingshot-like rubber band-powered launcher, the Autogiro, upon reaching its apogee, extended its folding wings and rotated earthward standing on its tail.

Lorin Wright’s death in 1939 sapped family interest in the toy business. The Millers sold Miami Wood to Lowell Rieger, who changed the name to the Wright-Dayton Company. Rieger traded heavily on the Wright connection, incorporating Orville and Jacobs into his advertising copy, until 1947, which saw the company introduce its final product, the Wright-Dayton Collapsible Wood Ironing Board.

This story was originally published in the October 2021 issue of American History Magazine. To subscribe, click here.