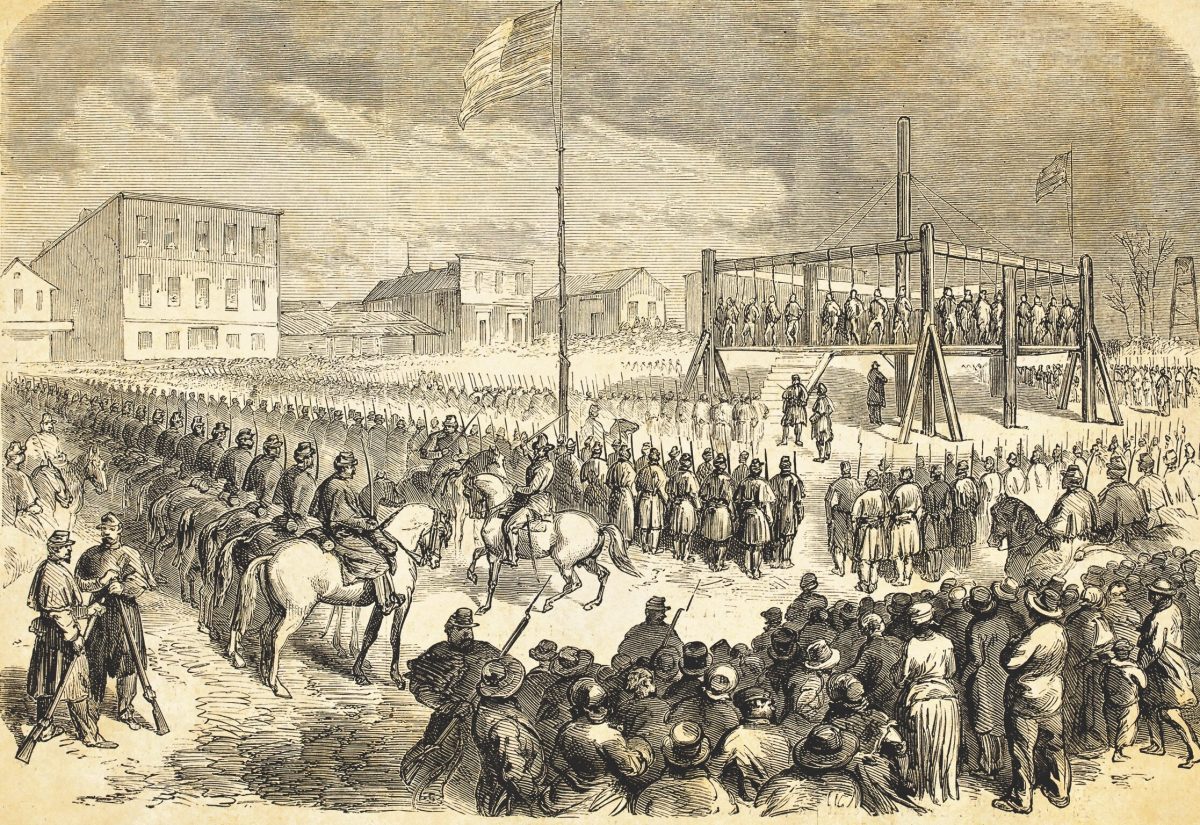

On the morning of December 26, 1862, 38 men were hanged on a single gallows in Mankato, Minnesota. It was the largest simultaneous execution in American history. The execution of these men, all Dakota Indians, closed the first chapter of the most violent American Indian war of the 19th century. It was a short war, with actual fighting lasting only six weeks, but more lives were lost in this conflict than in any other war of the American frontier period.

In the aftermath of the carnage, the officer in command of U.S. Army forces in the field, Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley, convened a military commission to try Dakotas accused of various atrocities. This hasty, field-expedient tribunal conducted 392 trials and sentenced 303 defendants to death, ultimately resulting in the 38 executions.

Perhaps the worst miscarriage of justice, worse even than an innocent person being wrongly convicted of a crime, would be to convict someone of a crime that never occurred in the first place. Several lines of thought hold that this is precisely what happened to the Indians tried by Sibley’s highly controversial military commission. One contends that the violence that characterized the Dakota War of 1862 was completely legitimate for the simple reason that it was in accordance with the Dakota’s traditional, established practice of warfare. By this argument, even the deliberate, unrestricted killing of women and children was not a war crime and should not have been prosecuted under European-American codifications of lawful warfare.

The whole controversy over what constitutes a war crime, and whose concept of acceptable conduct in war is legally applicable, is complicated. The five officers who formed the court of the 1862 military commission trials (none of whom had any formal training in military law) believed that atrocities such as the killing of unarmed civilians were crimes warranting punishment. The question was whether the military commission was correct to apply European-American concepts of lawful warfare to what were long-established practices of warfare for the Dakota.

In 1758, a full century before the Dakota War, the Swiss jurist Emmerich de Vattel published The Law of Nations. Vattel’s treatise was a standard text for 19th-century American diplomats and soldiers, and his ideas had tremendous influence on the codification of the Articles of War the U.S. military used in the nation’s nascent years.

In 1862 numerous American commentators believed that the Dakota were justified in going to war and that their long list of grievances against the U.S. government, which had finally driven them to war, were legitimate. But nearly all of them also insisted that the way in which the Dakota actually fought the war was not justified, not legitimate, and not acceptable. They condemned the Dakota for what they characterized as barbaric excesses of violence, and the indiscriminate killing of women and children was the primary reason why so many voices in Minnesota in 1862 called for vengeance against the Dakota, rather than justice.

Vattel had anticipated precisely this sort of visceral reaction to wartime atrocities. “If you once open a door for continual accusation of outrageous excess in hostilities,” he wrote, “you will only…influence the minds of the contending parties with increasing animosity: fresh injuries will be perpetually springing up; and the sword will never be sheathed till one of the parties be utterly destroyed.” So it was in the Dakota War.

In discussions of American frontier history, one perspective argues that European-American observers are not qualified to criticize indigenous native cultures. Nothing in the traditional methods of warfare among the Dakota, this view would insist, can be described by so pejorative a word as “atrocity,” and European-American conceptions of proper warfare should not apply.

In many American Indian cultures, the practice of warfare made little or no distinction between men, women, and children or between the armed and the defenseless—almost anyone could be a legitimate target. “In intertribal wars,” notes Carol Chomsky, a professor at the University of Minnesota Law School, “almost all members of the enemy nation—including women and children—were legitimate targets of attack, and captives were rarely taken.” It was precisely this aspect of Indian warfare that had such an undeniable and negative influence on the military commission’s view of the defendants.

“Women, children, feeble old men, and sick persons, come under the description of enemies; and we have certain rights over them, inasmuch as they belong to the nation with whom we are at war,” Vattel wrote. “But these are enemies who make no resistance; and consequently we have no right to maltreat their persons or use any violence against them, much less to take away their lives.” This was precisely how the members of Sibley’s military commission understood the matter when they sat in judgment.

Vattel, of course, had never seen a Dakota. He was born and reared in central Europe, where the horrific ravages of the Thirty Years War a century earlier had laid waste to entire regions and killed hundreds of thousands of women and children and the aged and infirm. These were precisely the types of people whom the Law of Nations was envisioned to protect.

In war, the victor makes the rules and writes the history, and the brutal reality of vae victis (woe to the vanquished) has applied to conflicts across the entire spectrum of human experience. But American concepts and definitions of lawful warfare are the only ones that bear on the Dakota War because all parties involved in the conflict—American soldiers, American civilians, and, most important, the Dakotas themselves—used those concepts and definitions to frame their views of the war at the point of its conclusion. The Dakotas adopted American ideas of lawful warfare when, in one extremely important instance, it seemed in their best interest to do so: at the point of their surrender to the U.S. Army, when they expected to be treated as prisoners of war. Consequently, they inadvertently accepted that American rules of war also applied to them.

At the same time, some commentators failed to acknowledge that European-American tacticians had long recognized preemptive strikes or surprise attacks—which the Dakotas certainly used in the first days of the war—as legitimate. They came with certain risks, however. “The opening of hostilities through a sudden raid,” the German tactician Herman Froetsch observed, “is politically a severe handicap which, while it may be lightly considered at the commencement of a war, is likely to have very unfortunate consequences should the war turn out badly.” What compounded the consequences for the Dakota was that they had made their surprise attacks not against purely military targets but rather against civilians, and in the eyes of many Americans, that utterly negated the legitimacy of such tactics.

In 1862 the argument over POW status for the defeated Dakota went back and forth as autumn gave way to winter. “We cannot hang men by the hundreds,” Episcopalian bishop Henry Whipple wrote to Senator Henry Rice. “Upon our own premises we have no right to do so. We claim that they are an independent nation & as such they are prisoners of war.” But Whipple was distinctly in the minority. “I think you are in error in saying they are prisoners of war,” Rice wrote in his reply to Whipple. “In my opinion they are murderers of the deepest dye. The laws of war cannot be so far distorted as to reach this case in any respect.”

One of the most complete accounts from the Dakota perspective comes from the narrative of Chief Big Eagle. He had not favored the idea of war against the Americans, but once the die was cast and war broke out, he was an active combatant. “I and others understood,” Big Eagle said, “that Sibley would treat with all of us who had only been soldiers and would surrender as prisoners of war, and that only those who had murdered people in cold blood, the settlers and others, would be punished in any way.” (In fact, Sibley initially felt that the Indians were not “entitled to be considered in the light of prisoners of war, but rather as outlaws and villains.”)

More than 30 years after the war, Big Eagle was still understandably bitter about being treated like a common criminal rather than a surrendered soldier from a sovereign nation waging a legitimate war. “If I had known that I would be sent to the penitentiary I would not have surrendered,” he said. “I surrendered in good faith, knowing that many of the whites were acquainted with me and that I had not been a murderer, or present when a murder had been committed, and if I had killed or wounded a man it had been in a fair fight, open fight.”

So what was the applicable definition of legitimate warfare in 1862? As is true today, it was accepted that in open war between states, soldiers on each side were entitled to protection from the normal legal prohibitions against killing and destruction. This does not mean, however, that all acts of violence in the course of war are automatically condoned. Vattel addressed exactly this question in The Law of Nations: “Even he who had justice on his side may have transgressed the bounds of justifiable self-defence, and been guilty of improper excesses in the prosecution of a war whose object was originally lawful.”

While prisoners of war are entitled to humane treatment and protection, Vattel went on to argue, they are still subject to the prosecution of law when it is appropriate. “As soon as your enemy has laid down his arms and surrendered his person,” he wrote, “you have no longer any right over his life, unless he should give you such right by some new attempt, or had before committed against you a crime deserving death.” This was precisely the principle that the military commission tribunal applied in its trials of the Dakotas. The incidents of murder and rape with which some defendants were charged were crimes under military law, as well as violations of civilian criminal law. In light of this, even prisoners who were otherwise protected as prisoners of war could still be charged and tried for crimes they had committed during the war.

Culture, in and of itself, is not an adequate defense against charges of war crimes, especially not when the culture in question subordinates itself to the victors’ laws of war to secure the protections of those laws once the war is over. Under those circumstances, the U.S. Army had sufficient jurisdiction and legal grounds to prosecute those Dakotas who were implicated in war crimes such as rape and murder, and the utterly flawed trial process itself does not change that salient fact.

There may be no historical precedent where a belligerent facing enemy actions it believed to be reprehensible and illegal subordinated its own laws, customs, and military regulations to find some way of accepting those actions.

It is also undeniable that the U.S. military, though ostensibly adhering to moral and legal codes that prohibit the targeting and killing of protected noncombatants, has occasionally failed to abide by those laws. Perhaps the most egregious example was in World War II, when the U.S. military obliterated cities in Germany and Japan with saturation bombing. The civilian populations of those cities were deliberately targeted in a controversial belief that doing so would break the enemy’s will to continue the war. Hundreds of thousands of civilians were killed, including untold numbers of women and children. In almost any other circumstance, those people would almost certainly have been classified as victims of war crimes. U.S. Army Air Corps General Curtis LeMay himself, who directed the firebombing campaign against Japan that killed more than 220,000 civilians, later said, “I suppose that if I had lost the war, I would have been tried as a war criminal.” The existence of a culture or doctrine that permits indiscriminate killing is indefensible whenever it occurs, and it remains the responsibility of law to confront such injustices even generations after the event.

John A. Haymond is the author of Soldiers: A Global History of the Fighting Man, 1800–1945 (Stackpole Books, 2018) and The Infamous Dakota War Trials of 1862: Revenge, Military Law, and the Judgment of History (McFarland, 2016).