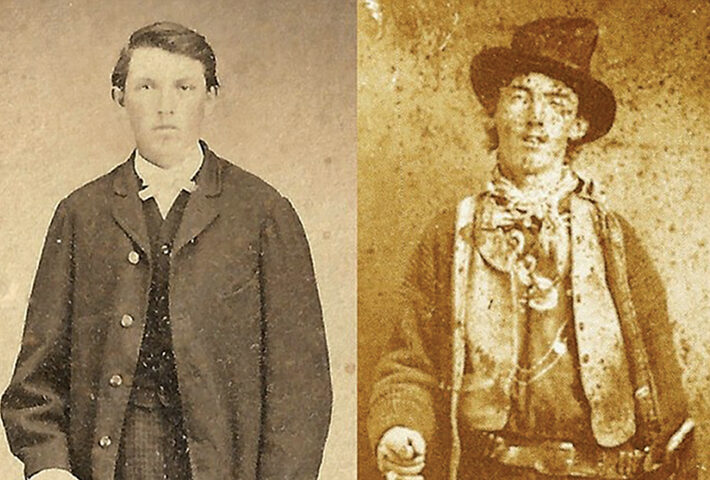

The tintype may be as tarnished as the outlaw himself, but it has obtained legendary status as a one-of-a-kind treasure.

The one and only authenticated photograph of Billy the Kid sold at auction in June 2011 for $2.3 million—the highest amount ever paid for a historic image of the American West. The sale to collector William I. Koch naturally created a buzz that extended beyond the outlaw and lawmen aficionados to the public at large. The buzz has barely died down. Billy has long been a frontier legend; now the only known photograph of him has become legendary. Historians continue to study him and learn more about his life (mysteries do remain, of course). It’s high time for a closer look at his photograph, perhaps the world’s most famous tintype. The poor condition of the tintype speaks for itself. To understand the anomalies in the image and the damage it has sustained, one must understand how a tintype is fabricated, taken and processed, and how it weathers the years. Drawing on what tintypers themselves said about their craft, the common procedure for posing and taking a picture, and the visual information contained in the image itself, it is possible to reconstruct with reasonable accuracy the 1879–80 “shooting” of William H. Bonney (as the man we call Billy the Kid called himself at the time).

The Tintype and the Tintyper

The ferrotype was a direct positive image in black, gray and silver pigment supported on a sheet of ferris iron. The photographers who took ferrotypes and the customers who bought them from 1856 through the turn of the 20th century called them “tintypes,” although they contained no actual tin. A tintype could be processed in minutes and was inexpensive, costing anywhere from a nickel to a quarter vs. the dollars charged for paper photographs. Tintypes were also durable and thin enough to be mailed in a letter. They were used primarily to capture full-length portraits. Tintypes were tiny images but, when properly exposed and processed, rendered fine detail.

Some tintypers, as the photographers called themselves, were artists who took portraiture and landscape photography seriously, while others were technically adept cameramen who learned the finer points of posing. All were businessmen. A tintyper could capture one image up to 32 times on the same sheet if he had the lenses and the septums (dividers) and/or the repeating back. He then cut the sheet into plates to sell individually or in quantity. Tintypes were inexpensive for the customer, lucrative for the tintyper.

The identity of the photographer who tintyped Billy Bonney is unknown, but the tintype itself and other probable examples of his work tell us something about him. He had a basic knowledge of camera operations and processing, but his tintypes exhibit little knowledge of lighting and portraiture, an overall carelessness and crude skills. He was most likely a New Mexican who thought to try his hand at photography. He may have learned the trade by working as a photographer’s assistant, or he may have bought a used tintyper’s outfit, read a manual and started practicing.

In the isolated mining camps and villages of the territory, photography remained a novelty in 1880, and people were willing to spend nickels and dimes on tintypes. The itinerant photographer hauled the gear in a coach or wagon, using the inside for a darkroom and the outside to display tintypes in various sizes and groupings. He had an assistant to help set up gear, deal with customers and capture the light.

From the look of this image the tintyper traveled light, without a posing chair, table, pictorial backdrops or cumbersome props. His equipment included a small four-lens camera, a four-window septum, a tripod, a box (or cabinet) containing the necessary chemicals and a supply of 5-by-7-inch iron sheets, pre-japanned at the factory. He may have used an Anthony four-lens camera, available through the mail in an inexpensive kit. The tintyper also used a headrest comprising a vertical iron rod adjustable to the customer’s height. The rod screwed into a three-pronged base, and at the top another rod extended horizontally with a clamp at the end that fit behind the ears. Customers never liked it, but it held heads steady for long exposures. Additionally, the tintyper carried a large backdrop (a wool blanket or a roll of paper) that absorbed light instead of reflecting it. This he would hang from a portable frame or suspend it from a ceiling or wall. He used a reflector to bounce fill light into shadowed areas. In this case the reflector appears to have been a sheet of white muslin (some experts think paper) unrolled from two poles and stretched the length of the assistant’s arms—cheap but practical.

The Location

Where and when the Kid stood for his portrait rests solely on the word of Walter Noble Burns, author of The Saga of Billy the Kid (1926). “It was taken by a traveling photographer who came through Fort Sumner in 1880,” Paulita Jaramillo (nee Maxwell) supposedly told Burns in 1924. “Billy posed for it standing in the street near old Beaver Smith’s saloon.”

Fort Sumner was a decommissioned military post on the Llano Estacado, 114 miles south of Las Vegas and 93 miles north of Roswell. Pathfinder Lucien Bonaparte Maxwell purchased the adobe buildings in 1872. When he died, Fort Sumner became the ranchero of his widow, Ana Maria de la Luz Beaubien. The 1880 census records the following people in the household: Luz Maxwell, 48; Pedro Maxwell, 32; Paulita Maxwell, 16; Odile Maxwell, 10; and Deluvina Maxwell, 22. The sparsely populated hamlet, where everybody knew each other—and each other’s business—was also a stopping place for roaming sheepherders, cowboys and travelers.

The exact location of Henry A. “Beaver” Smith’s grocery store, cantina and post office was pinpointed on a diagram drawn in 1927 by old-timer Charles W. Foor, who succeeded Smith as postmaster. He placed the store at the west end of what used to be the infantry quarters, a long adobe that stretched east to west along the southern boundary of the parade ground and turned, L-shaped, onto the Avenue, as the main wagon road was known. In 1880 its rooms sheltered hangers-on and housed the shops of Don Pedro’s business partners. At first Smith’s business faced the Avenue, but as the adobe became more unstable, it is thought Smith kept moving the store up the row, until he settled in the second and third rooms, where researcher Robert N. Mullin placed him in a 1920s diagram after interviewing several old-timers.

Northbound riders from Lincoln and Roswell would ride up the Avenue and turn east toward the parade ground. Smith’s store, cantina and post office were in the first occupied building they would see. Across the street was a building that had been converted from officers’ quarters into a dance hall. The front room facing the parade ground often doubled as a bar during the community bailes.

“Many people stopped at Mr. Smith’s house,” A.P. Paco Anaya, a teenage contemporary of the Kid and son of sheep raiser Jesús Anaya, recalled in 1931. “Billy and his pals always ate at Mr. Smith’s restaurant.” It is the one place the Kid would most likely encounter an itinerant photographer.

It is not difficult to imagine the tintyper driving his wagon down the Avenue in the winter of 1879–80 and rolling to a stop at Beaver Smith’s saloon, in which Pat Garrett tended bar and William Bonney dealt three-card monte. In isolated Fort Sumner this would be a community event, and like most everyone else Bonney would be curious.

No doubt the tintyper perceived his customer the same way a reporter from the Las Vegas Gazette did on December 27, 1880:

He is about 5 feet 8 or 9 inches tall, slightly built and lithe, weighing about 140; a frank open countenance, looking like a schoolboy, with the traditional silky fuzz on his upper lip; clear blue eyes, with a roguish snap about them; light hair and complexion. He is, in all, quite a handsome-looking fellow, the only imperfection being two prominent front teeth slightly protruding like squirrel’s teeth, and he has agreeable and winning ways.

Finding the Light

Had Billy Bonney posed in direct sunlight, or even in the shadow of a building, the harder light would have rendered sharper contrasts—shadows beneath his hat, under his nose and chin, and beside his feet. The tintyper did not use a flash, as it would have cast similarly hard light, sharp contrasts and shadows. Use of a reflector would lighten such shadows but not eliminate them. Thus the absence of shadows, the diffused lighting and neutral background suggest an indoor setting, perhaps in a portable tent or improvised studio. But no known building in Fort Sumner had the necessary skylight or a wall-sized window in which to set up a temporary studio.

On closer examination the Kid’s slightly windblown appearance suggests another possibility, one that makes a portable tent unlikely. The right lapel of Bonney’s vest is turned up (or rather blown up), and his scarf is blurry, as if in motion, blurrier than the shirt behind or the hand in front. This is clearly an outdoor posing on a windy day.

After parking his wagon in front of Smith’s store, the tintyper did what photographers do: He faced north and looked to his left and right to find both diffused light and protection from the wind blowing across the parade ground. If, as Paulita Maxwell indicated, the tintyper did choose Smith’s store and saloon as the best place to park his wagon and attract customers, he had only to look across the street to the dance hall for a place to pose them.

The dance hall had a deeply recessed portico that wrapped around two sides of the building. Outside at ground level was dirt instead of a boardwalk. Beneath the portico roof the tintyper would find diffused light and sufficient protection from the wind to take outdoor pictures without making too much fuss over the aesthetics of portraiture. The tintyper and/or his assistant would hang the backdrop, put the headrest into position in front of it, lean the rolled-up reflector against the adobe wall and mount the camera on a tripod about 15 feet from the headrest. With a northern light behind him and eastern light beside him, the camera facing south and the customer facing north, the tintyper had a setup and lighting conditions that correspond reasonably to those manifested in the tintype of Billy the Kid.

The Posing

Billy Bonney decided to pose with his firearms, like compadre Charles Bowdre had done sometime before in a carte de visite Bonney had likely seen. Photographers in New Mexico Territory were accustomed to this. Everyone traveled armed, even photographers, and some photographers kept firearms as portrait props. As soon as Bonney agreed to pose for a portrait, the procedure unfolded as it would for any other customer:

Leaving his assistant to attend to the customer, the tintyper enters the darkroom to sensitize a plate. From a supply box he takes an iron sheet already coated with lampblack (or copal varnish or linseed oil). He pours collodion from a bottle onto the plate, which he tips and tilts until the syrupy substance covers it evenly from edge to edge. He then shutters the room, and working by candle in a yellow glass chimney (a safelight), he fills a shallow tray with silver nitrate from a light-sealed bottle. Placing the pre-coated plate into this bath, he gently agitates it to and fro for about a minute, until the collodion takes on a creamy yellow appearance. He pours the excess back into the bottle and returns the bottle to a light-sealed box. He inserts the now-sensitized plate into a thin wooden holder, also light-sealed.

Meanwhile, the assistant asks the customer to stand before the backdrop. Bonney steps into position, his left side toward the wall of the dance hall, his right side some feet from the open. The blanket hanging behind him obscures Smith’s saloon. Squinting into the winter light, Billy sees before him a camera on a tripod under the eaves of a wide portico, beyond it the home of the Maxwells. Maneuvering the arm of the headrest, the assistant positions the clamp behind Billy’s ears, reassuring him the discomfort will last only a few minutes. The assistant asks Billy to uncradle the Winchester carbine from the crook of his arm (the natural carrying position) and lean on it, as such a prop helps a subject keep still. He then pushes back the sweater on Billy’s right side to show off the Colt. The assistant then advises Billy that when the tintyper comes out of the darkroom, he should look directly at the camera and remain motionless until otherwise instructed. The assistant takes position behind the reflector, which he has unrolled from two poles to form a smooth white surface.

The tintyper emerges from the darkroom with the sensitized plate in its light-sealed holder. Ducking beneath the hood, he sees four identical images of Bonney in the ground glass (viewfinder)—two over two, upside-down and reversed. He adjusts the pan, tilt and height of the camera to ensure the customer is centered in the frame. He adjusts the back-focus knob, pulling the bellows back until the head is focused in the ground glass. This is a bit of a trick to get right, as the top row is not in the same range as the bottom row, and the left images are not in the same range as the right images. (History will preserve the Dedrick plate, in which the hand holding the rifle is sharp, the figure behind the hand out of focus.) The tintyper instructs his assistant to angle the reflector in close and then tilt it back to bounce light on Billy’s left side, cast into shadow by the strong sidelight.

The shallow depth of field and the intrusion of a reflector in the posing space call into question the tintyper’s judgment. If the tintyper notices his assistant’s fingers gripping the reflector, he does nothing to correct the intrusion. Ready to take the picture, the tintyper steps to the side of the camera and caps the four lenses, probably with a heavy velvet cloth, sealing the box from light. He then opens the ground-glass door at the back, fastens the plate holder tightly over the four-image septum and is ready to expose the plate to light.

Although such preparations took only a few minutes, it was common, then as now, for the customer to relax his posture and assume a distracted expression. Some people need to be posed; others are naturally attentive and engaging. Bonney looks alert, interested and amused. He is actually smiling, a rare thing in 19th-century photography. An experienced photographer poses a figure in complimentary ways, but this tintyper probably went no further than to ask Billy, without moving his feet, to push out the holster and rotate the rifle into profile so that the lever and loading gate are visible. He no doubt reminded Billy to stand up straight, look directly into the camera, try not to blink and remain absolutely still.

Bonney complies. The tintyper raises the dark slide out of the camera and uncovers the lenses. Using a stopwatch, he counts off six to 10 seconds, then recovers the lenses and reinserts the dark slide. The plate has been exposed, and the tintyper tells the heavily armed teenager he can move about now. The tintyper removes the plate holder from the camera and reenters the darkroom to develop, fix, dry, varnish and trim the plate.

The Processing

Working by safelight, the tintyper immerses the sticky iron plate into a tray of pyrogallic acid and gently agitates the tray for one to two minutes, rapidly converting the negative into positive images. After quickly rinsing the plate in water, the tintyper fixes (stops) development by immersing the plate in a solution of potassium cyanide from two to five minutes. Now working in ordinary light, the tintyper again rinses the plate in water and dries it by warming it over a flame (not too close). The tintyper varnishes the plate, either with a brush or by pouring the clear solution over the front surface, then again warms it dry.

Certain anomalies occur during this process. Viewing the Dedrick plate under a microscope, one can see specks of gray matter embedded in the varnish, as if the tintyper had dropped cigar ashes (or something) onto the plate before it dried. The clear varnish serves as a protective coating for the image in the collodion and silver nitrate beneath. The tintyper didn’t wait for the plate to completely dry, however, before moving on to the next step. To separate the four images, he cut horizontally along the center and then vertically across the middle. Perhaps his hands were unsteady, or his tin snips were bent, as both cuts are irregular. The left and top edges of the Dedrick plate are at factory-made right angles, indicating it is the upper left image on the sheet, while the bottom and right edges are ragged. He trimmed the right side unusually close, perhaps leaving the edge of the image on the adjoining plate. He then cut the four corners at a 45-degree angle to they wouldn’t poke through a paper window mat. In doing so, his thumbs blotted the bottom corners, indicating the varnish was still tacky when, presumably, he brushed paste across the recto surface, pressed on a paper backing and enclosed the plate in a folding paper window mat.

The varnish on a freshly made tintype dries from the outer edges inward. Evidence that the varnish remained sticky when the tintyper handed the Dedrick plate to Bonney is the ribbed pattern across the lower center of the image, likely made when the tintype came into contact with fabric, such as the customer’s vest pocket.

When the tintyper presented Bonney with four sticky mug shots instead of four portraits, Billy would have been justified in shooting him on sight. (Had he done so, there would be a record of the tintyper’s name.) Like any other customer, Billy paid his two bits and no doubt spent some minutes gazing into his tiny mirror image, frozen in time. It was an uncommon experience, perhaps even a revelation, to see himself the way others did.

The Plates

There were originally four plates. The Pat Garrett plate, probably taken from the Kid when the sheriff apprehended Billy in December 1880, must have served as the basis for a woodcut published in The Illustrated Police News, Law Courts and Weekly Record on January 8, 1881. The woodcut (some say steel engraving) Garrett included in his 1882 book, The Authentic Life of Billy the Kid, is also based on this plate. The McGraw plate was reportedly a gift from the Kid to Patrick McGraw, a miner and store owner in Lincoln County’s White Oaks mining camp, who later gave it to his son John. The Deluvina plate is named for the Navajo woman who lived with and worked for the Maxwell family and was a devoted friend of Billy’s. The Kid reportedly gave it to her as a gift. Western author Emerson Hough saw the Deluvina plate in Fort Sumner in 1904 and shot a copy negative of it. In Chicago, Hough had a silver gelatin print made that was the source for two halftones in 1907. The plate itself, according to Paulita Maxwell, was destroyed in a house fire.

The Dedrick plate is the only one still around. Billy the Kid gave this plate to Bosque Redondo friend Daniel C. Dedrick, who later gave it to his nephew Frank L. Upham. In March 1986 the Upham family reached an agreement with John L. Meigs of the Lincoln County Heritage Trust for an exhibit loan of the tintype. Meigs immediately had archivists at the Museum of New Mexico in Santa Fe shoot a roll of 35mm copy negatives—the first copies ever made of the plate. The negatives showed the tintype to be in alarming state. Exposure to bright light, air and changing temperatures had dimmed the image. The protective outer layer of varnish had long since rubbed off. Coating the surface of the plate was a century of fingerprints and accumulated grime that had fused with the imaging silver. Someone had punched holes through all four corners, apparently to display the tintype, causing bends and crimps across the plate, in turn creating visual distortions. Rust was emerging from dents, nicks and abrasions. These were old injuries that had been left festering for decades.

In 1998 the Lincoln County Heritage Trust dissolved, and the tintype reverted to the Uphams (Frank and Dan Upham had since passed away). In June 2011 heirs Stephen Upham of California and Art Upham of Arizona put up the tintype for auction through Brian Lebel’s Old West Show and Auction at the Denver Merchandise Mart. When I examined the tintype in Lebel’s office in March 2011, additional deterioration was apparent. Rust had begun to seep out of the iron sheet and spread across the entire plate. It manifests as a red color, which was barely visible in a few specific areas of the tintype when recovered in 1986.

The Image

Photographers, artists and digital retouchers have subjected the image of William H. Bonney to numerous alterations over the years, all derived from Emerson Hough’s 1907 halftones. They have fixed flaws, cleaned up the background and fleshed out the face, which was indistinct and washed out in the halftones—each seeking to prove that his interpretation of Bonney’s personality and character is the “correct” one. But there is no substitute for the real thing.

In his only authenticated photograph Bonney squints into the camera with a “jaunty daredevil kind of an expression,” to quote a period reporter. Although out of focus, the image does capture the intelligence, willfulness and cheerful demeanor so many of his contemporaries describe. He stands ready to meet any challenge, with his Winchester carbine and his Colt Single Action Army at hand, no doubt loaded and ready to fire. It is the classic gunfighter stance seen in hundreds of Westerns, but the Kid is not posturing. Nor is he showing off. The stance comes naturally out of the extraordinary life he has lived. This is a teenager who fought to survive in a territory with little law and order. To judge the image of the smiling Kid with guns as some kind of nut is to impose contemporary standards on frontier conditions and indicates just how disassociated we have become from our past.

“I never liked the picture,” Paulita Maxwell told author Burns. “I don’t think it does Billy justice. It makes him look rough and uncouth. The expression of his face was really boyish and very pleasant. He may have worn such clothes as appear in the picture out on the range, but in Fort Sumner he was careful of his personal appearance and dressed neatly and in good taste.” She added that at the weekly dance at Fort Sumner, Billy Bonney cut a gallant figure. “He was not handsome,” she said, “but he had a certain sort of boyish good looks. He was always smiling and good-natured and very polite and danced remarkably well, and the little Mexican beauties made eyes at him from behind their fans and used all their coquetries to capture him and were very vain of his attentions.”

If indeed the tintype was taken at Fort Sumner in the winter of 1879–80, it captures Bonney at a moment when he has everything to look forward to. He has fought in the Lincoln County War to avenge John Tunstall’s murder and testified at the Dudley Court of Inquiry to right the wrongs he may have committed. Now he awaits the amnesty promised by Territorial Governor Lew Wallace. He is in love with Paulita Maxwell, and while he waits for her to come around, other women vie for his attentions. He has strong friendships, and he does not yet know what awaits him.

It would be nice if there were a studio portrait of William H. Bonney that clearly and sharply defines his features. But no studio portrait could capture the spontaneity and immediacy of the unrefined mug shot. To gaze into this full-length portrait is to witness the American West defined. Perhaps it is poetic justice that the tintype is as rough as the times in which Bonney lived and as tarnished as his reputation. As rust and corrosion consume the tintype itself, copy negatives, prints and electronic scans ensure that Billy the Kid will always fight his way through the scrapes and dents of the past and into our present consciousness.

Richard Weddle, who studied the image for the Lincoln County Heritage Trust from 1989 to 1994, has written Billy the Kid: An Iconographic Record, a book-length study of the tintype waiting to be published. He dedicates this article to John L. Meigs (1916–2003), who, he says, “is responsible for the recovery of the tintype of Billy the Kid.”Weddle also thanks Brian Lebel of the Old West Show and Auction [www.denveroldwest .com] and Grant B. Romer and Mark Osterman of the George Eastman House Museum of International Photography [www .eastmanhouse.org] for their assistance.

Originally published in the August 2012 issue of Wild West. To subscribe, click here.