Disastrous midterm campaign tour was a shortcut to impeachment

ABOARD THE BALTIMORE & OHIO train departing Buffalo, New York, for President Andrew Johnson’s 1866 mid-term campaign swing, General of the Army Ulysses S. Grant was drunk—and not mildly, but falling-down, all-the-way-in-the-bag drunk. A companion saw Surgeon General Joseph Barnes “go up to Grant to feel his pulse;” Barnes found the Civil War hero “so drunk he tumbled down on him.” Gideon Welles, Johnson’s dyspeptic secretary of the Navy, reported that as the train was rolling to Cleveland, Ohio, Grant became “garrulous and stupidly communicative.” Grant’s aide, Maj. Gen. John Rawlins, and New York Tribune reporter Sylvanus Cadwallader, both of whom previously had seen him in this condition, quickly separated him from the presidential party. “Gen. Grant had to be taken into a baggage car; compelled to lie down on a pile of empty sacks and rubbish and remain there,” Cadwallader later reported. “Gen. Rawlins and myself stood guard over him…every mile of the way; locked out all callers for him; and protected him from observation as far as possible.”

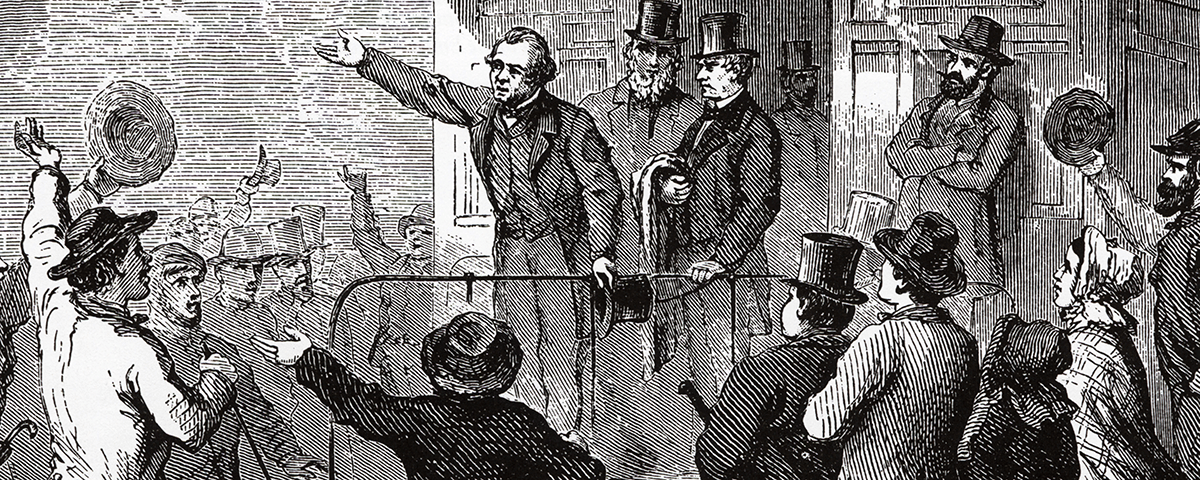

Grant and his minders were part of the contingent accompanying President Andrew Johnson on his “Swing Around the Circle,” an August 27-September 15, 1866, midterm campaign outing designed to promote the president’s moderate, conciliatory Reconstruction policies. Johnson and his entourage traveled from Washington, DC, to New York City, north to Buffalo, west to Chicago, and south to St. Louis,

returning to the capital by way of the Ohio Valley. The first few stops went well but gradually audiences grew more hostile, baiting the thin-skinned Johnson. Defensive, taking out personally against opponents, Johnson traded catcalls with hecklers, horrifying onlookers with behavior no president ever had displayed. Johnson’s vitriol on the “Swing Around the Circle” foreshadowed the rage-ridden final two years of his accidental presidency.

At Cleveland, rather than risk the effects on Grant of an impending two-day run to Detroit, Michigan, Barnes and Rawlins bundled the general onto a vessel that would get him to Detroit overnight. This may have been Grant’s last drunk, almost certainly triggered by his entanglement in an epically ill-conceived political campaign excursion.

Many Radical Republicans had greeted Johnson’s ascent by assassination with optimism, thinking he would go along with their program for enfranchising formerly enslaved African-Americans and putting the former Confederacy through a reconstructive, even punitive shake-up. “In the question of colored suffrage, the President is with us,” Massachusetts Republican Senator Charles Sumner wrote a colleague. “I had looked for a bitter contest on this question, but with the President on our side it will be carried.”

Johnson instead preferred reconciliation. A longtime loather of his home region’s planter class, the president enjoyed—perhaps too much—seeing circumstance turn his former social betters into supplicants. Observed Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Andrew Johnson, wont to look up to the planters as a superior race, cannot resist their condescensions & flatteries… [and was] an easy victim for their caresses.”

As Johnson showed willingness, even eagerness, to pardon former Confederates, the Republican-controlled Congress balked, during 1866 overriding 15 of 29 Johnson vetoes. These included the Civil Rights Act, which declared all persons born in the United States, regardless of race, color, or previous condition of involuntary servitude, to be citizens. That April 9, 1866, override vote was the first of an American president in more than 20 years. On July 16, 1866, Congress also overrode Johnson’s veto of the Freedmen’s Bureau Reauthorization Act, which granted aid to former slaves, such as food and housing, oversight, education, health care, and employment contracts with private landowners. Major white supremacist violence erupted across the South, notably in New Orleans. On July 30, whites there attacked African-Americans protesting recently imposed Black Codes, as postwar legislation that curbed blacks’ civil rights were known. Rioters injured 150 blacks, 44 fatally, and killed four whites.

In spring 1866, Navy chief Welles and Secretary of State William Seward, looking ahead to the fall elections, undertook to put Johnson in front of voters. The two planned a politicking foray to Chicago. The nominal goal was to unveil a memorial to Democrat Stephen A. Douglas, who had died of typhus in 1861; the real point was to rally voters to the president’s cause in November. Johnson took to the idea, pushing for more whistle stops as a means of enlisting northern Republicans to support him. He saw the junket as a way to exploit tensions between the party’s Radical wing and more moderate members to his own benefit.

Claiming not to care who rode along, only that “we should have plenty of company,” Johnson nonetheless latched onto the idea of inviting Ulysses Grant. The newly appointed general of the Army had been refusing to align with either the White House or Congress. Johnson aggressively wooed the Union hero, even crashing a reception the Grants were holding and inserting himself between the general and his wife as they were greeting invited guests.

A wary Grant dodged Johnson’s overtures about climbing onto the bandwagon, finally deciding “it would be indecorous any longer to object,” according to a confidant. Other Union military figures jumped to join in, such as the hero of Mobile Bay, Admiral David G. Farragut, and flamboyant Brevet Brig. Gen. George Armstrong Custer. Cabinet members signed up: Seward, Welles, and Postmaster General Alexander Randall. At the last minute Secretary of War Edwin Stanton begged off, citing a sick wife. Johnson’s personal entourage included his daughter Martha and son-in-law Senator David Patterson, who held Johnson’s former seat representing Tennessee; two secretaries; a security man; and Surgeon General Barnes. The only foreigner aboard was Matias Romero. The 29-year-old Mexican ambassador, in the course of lobbying for American support to evict the French from his country, had ingratiated himself with both Grant and Johnson.

At 7:30 a.m. Tuesday, August 28, 1866, Johnson and party departed Washington’s Baltimore and Ohio railroad station. Along with special sleeping and commissary cars, the B&O had laid on a car for the press—though Johnson had no interest in propitiating reporters he saw as pro-Congress and anti-Johnson, whether they represented major dailies or boondocks weeklies. Throughout the trip, no one got advance copies of Johnson’s remarks, often extemporaneous and often featuring hostile responses to catcalls. Reporters had no tables to facilitate note-taking, and often were shut out of banquets and other social events organized as part of the presidential progress, coverage of which was unprecedented and skewed. “With few exceptions,” noted The Nation, “the press of the country has sided with Congress in the issue raised by the President.”

After a pause at Annapolis, Maryland, the presidential train arrived in Baltimore to great enthusiasm. Seward and Welles had engineered a crowd of 100,000 to cheer Johnson’s amicable stance toward the former Confederate states. Johnson did not speak, but everywhere he went in the Maryland port city he was mobbed. Another large crowd turned out in Wilmington, Delaware, whose city council boycotted the fete. Philadelphia’s mayor being conveniently out of town, a delegation from the Merchant’s Exchange met the president at the station. Johnson briefly lambasted absent city leaders and Thaddeus Stevens, the Radical Republican House member from Pennsylvania, before retiring for the evening. The next morning his train departed for New York.

En route, unsolicited advice showered Johnson. Late to board, Senator James Doolittle (R-Wisconsin) exhorted the president to eschew “extemporaneous speeches.” Johnson had taken care in writing not to provide enemies with ammunition, Doolittle said. “But what you have said extemporaneously…has given them a handle to use against you,” the other politician added. Welles had said much the same when planning the trip, to the same result. “He manifestly thought I did not know his power as a speaker,” Welles recorded in his diary.

New York City, the nation’s largest urban center, greeted Johnson in style. Accompanied by two cavalry regiments and ranks of New York City police officers, the president rode past 200,000 cheering onlookers to City Hall, where he reviewed a parade. That evening at Delmonico’s, addressing editor Horace Greeley, power broker Thurlow Weed, and financier Cornelius Vanderbilt among 250 banquet guests, Johnson made an impassioned plea for his moderate Reconstruction policies. The defeated Confederate states, he argued, “are not fit to be a part of this great American family if they are degraded and treated with ignominy and contempt.” He received a standing ovation.

Riding the rails north along the Hudson, the party paused at Manhattanville so Custer and his wife could board. At Albany, the atmosphere turned grim when New York Governor Reuben Fenton refused to introduce Seward to the legislature. Johnson spoke anyway, expressing what would become a motif for the trip—the “slander and calumny [of] a mercenary and subsidized press.” In Auburn, Seward’s home town, a boy running alongside Grant’s carriage fell under the wheels; the accident cost him a leg. “I am getting very tired of this expedition and of hearing political speeches,” Grant wrote to wife Julia. “I must go through however.” He was not alone in his discomfort. Matias Romero bemoaned the “torment which this journey has become.” As the train was crossing northern New York, Johnson kept slamming newspapermen as “mendacious and unprincipled writers” whose primary goal was to “traduce and vilify” him. At Buffalo, former president Millard Fillmore lauded Johnson as “a rock in the midst of an ocean, against which the waves of rebellion dashed in vain.”

As the presidential party was preparing to leave Buffalo for Cleveland, Johnson clashed with a heckler. “Keep quiet ’till I have concluded,” the president told his interlocutor. “Just such fellows as you have kicked up all the rows of the last five years.” This confrontation previewed events in the Midwest, where Johnson and his policies were unpopular. Ohio’s Radical Republican Senator Benjamin Wade accused Johnson of “consigning the great Union, or Republican party…to the tender mercies of the rebels we have so lately conquered in the field.”

Johnson’s troupe, absent Grant and handlers, reached Cleveland around 8 p.m. on Sunday, September 2. After a meal, Johnson addressed an unruly crowd. “The president was frequently interrupted by cheers, by hisses and by cries, apparently from those opposed to him,” noted a local reporter. When Johnson challenged listeners to “place a finger upon one act of mine…in violation of the Constitution,” the crowd roared “NEW ORLEANS!” a reminder of the white supremacist violence that had bloodied that city’s streets only months before. Some shouted, “Hang Jeff Davis!”

“Why don’t you hang him?” Johnson replied. “Why don’t you hang Thad Sevens and [abolitionist] Wendell Phillips?” Johnson’s companions wondered why he didn’t simply shut up. When Doolittle criticized the president’s deportment, Johnson shot back, “I don’t care about my dignity” and delivered what one paper called “the most disgraceful [speech] ever delivered by any President of the United States.” The New York Times said its editors “greatly regretted” Johnson’s casual dismissal of his dignity.

In Detroit, Johnson could have basked in the ardor of an upbeat crowd of 30,000 but instead he focused on a few hecklers. Asked about his annual salary of $25,000—today more than $356,000—Johnson angrily asked, “Has it been increased since I came into office?” He excoriated the Republican-controlled Congress for raising members’ salaries to $4,000. In the morning, before departing for Chicago, Johnson and party got an embarrassing reminder of the political stakes in play when black waiters at their hotel, in a protest against the president’s civil rights policies, refused to serve them breakfast.

Chicagoans, who had embraced Lincoln, felt little warmth for Johnson. Governor Richard Oglesby and the Chicago common council boycotted his visit, which drew respectful crowds that were smaller and much more subdued than those elsewhere. The Douglas memorial dedication in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood, the junket’s ostensible point, had no excitement. Accompanied by Mayor John Blake Rice and representatives of fraternal organizations, Johnson followed General John Dix’s lengthy recounting of the Little Giant’s achievements with brief remarks, saying that were Douglas to rise from his grave, he would proclaim, “The Constitution and the Union—they must be preserved.”

The “Swing Around the Circle” had been under way for nine days and many participants’ patience was wearing thin. “I am disgusted with this trip,” Grant told Sylvanus Cadwallader, a remark that made the front page of the New York Herald. “I am disgusted at hearing a man make speeches on the way to his funeral.” Mexican minister Romero, correctly intuiting that his continued presence would cost the Mexican independence movement Radical Republicans’ support, told Seward he was feeling sick. Within a few days Romero was gone. Turning south toward St. Louis, the presidential train stopped in Springfield, Illinois, so passengers could visit Lincoln’s tomb. Deciding the Johnson campaign was played out, the New York Herald recalled its reporters. A heckler called Johnson a traitor. “I have been called…Judas Iscariot. If I have played the Judas, who has been my Christ?” Johnson asked. “Was it Thad Stevens? Was it Wendell Phillips? Was it Charles Sumner? Are these the men that set themselves up and compare themselves with the Savior of man?” A New York Tribune headline summed up the event: “The President’s Trip From Springfield to St. Louis: He Denies That He Is Judas Iscariot.”

Grant grew exasperated. “I have never been so tired of anything before as I have been with the political stump speeches of Mr. Johnson,” Ulysses wrote to Julia. “I look upon them as a national disgrace.” In Indianapolis, raucous boos and jeers greeted Johnson’s attempt to speak, prompting Custer to admonish the crowd, “Hush, you damned ignorant Hoosiers!” Johnson gave up and retreated to the hotel, where a melee broke out. “Gentlemen, I am ashamed of you,” Grant told the roisterers. “Go home and be ashamed of yourselves.” Gunfire between pro-and anti-Johnson factions killed one man. A slug lodged in the wall of Johnson’s empty hotel room.

Grant heard a rumor that someone was offering $1,000 for Johnson’s assassination. He decided it was true. Other rumors swirling had the Grand Army of the Republic, a group for veterans of the Civil War and a harsh critic of Johnson, organizing riots and plotting to kidnap Grant, Seward, and Farragut.

What one New York City newspaper dubbed “the mortifying spectacle of the President going about…denouncing his opponents, bandying epithets with men in the crowd, and praising himself and his policies” continued for five days after Indianapolis. Custer left the party in Steubenville, Ohio; Seward, besieged by diarrhea, had to stay over in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, where for a time he hovered near death. During a stop in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, a platform constructed over a dry canal collapsed under the weight of 400 onlookers, killing at least six and injuring many more. Johnson wanted to stay to console the people, but train schedules forbade that. To help survivors, he contributed a check for $500—about $8,400 today. Critics pounced. The president had “manifested anything but a humane feeling in moving off at the very height of the people’s distress,” a local editor wrote. The 18-day “Swing Around the Circle” ended as it had begun, with a warm reception in Baltimore. Grant went home. Seward was still in Harrisburg. The leg to Washington ended near dark on September 15 amid excited crowds jamming the B&O terminal and lining the route to the White House. Of the luminaries who had begun the junket, only Welles and Farragut remained.

The “Swing Around the Circle” was an unalloyed disaster. Little-known beforehand, Johnson now was cemented in the national awareness as a demagogue. In his memoir, William Crook, the president’s bodyguard through the trip, remembered that Johnson’s abrasive encounters on the journey “were immediately telegraphed over the country…. After this there was no possibility of stemming the tide of unpopularity. They lost the President the elections. The President figured in the public mind as almost a monster.”

A few skeptics blamed Seward. Abolitionist Lydia Maria Child, who characterized Johnson as “a braying ass,” speculated that the “wily fox, Seward, encourages him to bray on purpose to disgust the people and so give himself a chance to saddle and ride the new party.” The New York Herald asked if the “‘Mephistopheles Secretary’ still has ambition to take the Presidential chair” and if he accordingly had planned the grand tour “for the purpose of damaging the President.”

But most blame accrued to Johnson. The Potter County Journal, a small Pennsylvania paper, editorialized: “If he would stay in the White House, keep his mouth shut, and not make a fool of himself, disgusting friend and foe alike…the President of the United States might

command some respect.”

When Congress sought to remove Johnson from office in 1868, the tenth article of impeachment directly referred to the notorious campaign swing, describing “certain intemperate, inflammatory, and scandalous harangues…against Congress.” Former Union General Benjamin Butler, who co-managed the House impeachment proceedings, argued that Johnson’s speeches during the presidential trip had been too incendiary. “We are too apt to overlook the danger which may come from words,” Butler said. “But words may be and sometimes are…living things that set the world on fire.” For lack of support, the article was not brought to a vote.

The sole beneficiary was Ulysses Grant. “General Grant’s presence and name excited much more enthusiasm than Johnson’s presence and name,” Matias Romero wrote. “[Crowds] interrupted the president when he has wished to speak and cheered the general to the point of proclaiming him the next president.” Grant’s father embarrassingly touted his son for the presidency. In a letter to The New York Times soon after the trip, Jesse Grant wrote, “If there should seem to be the same necessity for it two years hence, as now, I expect he will yield.” His days on the trip left Grant more politically astute. Realizing Andrew Johnson’s administration was doomed, the general vowed never again to let the president exploit his popularity but did not cut the president dead. In August 1867, Johnson was trying to force Edwin Stanton to resign as secretary of war and to remove Generals Phil Sheridan and Dan Sickles as military commanders overseeing Reconstruction in New Orleans and the Carolinas. Getting rid of these three Union stalwarts, the general warned Johnson by letter, would be more than the “loyal people of this country (I mean those who supported the Government during the great rebellion) will quickly submit to.” As usual, Johnson ignored Grant. His impeachment brought into bleak bloom the seeds he had planted during his self-destructive Swing Around the Circle.