Were it not for the efforts of two men who settled in the town of Willows, California, the August Complex Fire, the largest in the state’s history, might have devastated even more than the million acres it ravaged during the seemingly endless fire season of 2020.

Those two men were Floyd “Speed” Nolta and Joe Ely, and they pioneered the use of airplanes to drop water on forest fires. They had contrasting backgrounds—Floyd from a blue-collar timbering family in Oregon and Ely an Ivy League Midwesterner—but together they provided an example of American ingenuity at work.

Nolta was already a highly regarded mechanic at 17, when he enlisted in the Army after the United States entered World War I. The Army sent him to Rockwell Field near San Diego to serve as a mechanic. (While at Rockwell, Nolta met Jimmy Doolittle, not yet a legendary aviator, and the two men became lifelong friends.) Nolta had his first airplane flight while in the Army, and he learned to fly after the war when he settled in Willows in Northern California’s Sacramento Valley. There he formed the Willows Flying Service to provide crop dusting services.

In 1928, Nolta developed a way to speed rice planting by mounting a hopper on the fuselage of his Hispano-Suiza powered Travel Air biplane. A sliding valve with a threaded knob allowed him to measure precise amounts of fertilizer and seed that dropped from the hopper into a box. The wash from the propeller spread the product over a 50-foot swath. Nolta’s system vastly improved rice propagation. According to Thad Baker, a modern-day certified crop advisor and rice farmer, pilots around the world still use Nolta’s device.

In addition to agricultural flying, the Willows Flying Service had contracts to provide various services to the U.S. Forest Service. It flew personnel to remote areas, airlifted supplies, conducted aerial searches for fires and dropped seed for forest fire remediation.

While Nolta was building a career at Willows, a young man 11 years his junior was pursuing an Ivy League education that placed him on an intersecting trajectory. Born in Wisconsin in 1911, Joe Ely earned an undergraduate degree at Dartmouth College and obtained his master’s degree in botany from the Yale School of Forestry in 1935. He joined the Forest Service after getting his master’s, and he would spend his career there in a variety of posts.

When the United States entered World War II, forest rangers were exempt from military service because the government classified them as critical for protecting forests, particularly in the event of Japanese incendiary balloon attacks. Ely, therefore, continued his forestry career. In contrast, Nolta flew as a Hollywood stunt pilot before re-enlisting in the Army Air Forces and joining the First Motion Picture Unit. He piloted aircraft for training and morale-boosting films and flew a B-25 Mitchell bomber under the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge for Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo, a fictionalized account of his friend Jimmy Doolittle’s 1942 bombing raid on Japan.

Nolta and Ely both ended up in Willows after the war. Nolta continued his stunt work but returned to his flying service after recovering from serious injuries he suffered in a crash of a P-38 Lightning near Los Angeles in 1948. Ely eventually settled with his family in Willows after being promoted to Fire Control Officer in the Mendocino National Forest, one of the most active fire areas. Located in the Northern Coast Range Mountains, the forest covers 900,000 acres, has upwards of 6,000 feet in elevation change and features a mix of evergreen forest, oak woodlands and heavy chaparral woodland ecosystems. California chaparral is the densest brush in the world, consisting of trees and plants with waxy leaves and a high oil content that allows plants to survive dry summers, but also makes them highly flammable.

Those conditions led to tragedy on July 9, 1953, when the Rattlesnake Fire broke out 28 miles northwest of Willows. Fifteen young men, mostly 20-something missionaries serving as volunteer firefighters, lost their lives when they became trapped in a canyon by flames that raced toward them at 15 miles per hour. One of the men who died that day was a Forest Service ranger. It was the worst loss of life in the history of the U.S. Forest Service until 19 firefighters perished in the Yarnell Fire in Arizona in 2013. In reaction, the Forest Service and other agencies established Operation Firestop, a program to find workable ideas to fight fires. In the spring of 1955, Ely received permission from his supervisor to explore the possibility of using water drops as part of the program.

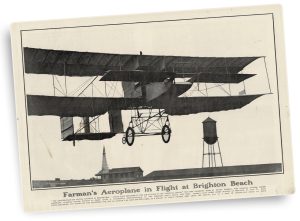

Dropping water from airplanes onto fires was not a new idea. It had been considered as far back as the 1920s, but none of the various methods tested after World War II had been implemented. Ely’s idea was to use the agriculture pilots in Willows to do the job. According to Ely’s handwritten account, “I took the air tanker proposition first to Lee Sherwood, the Airport Manager, and perhaps some others, but they were looking out the window. Anyhow Floyd (Speed) Nolta, of the Willows Flying Service caught fire real fast. All I had to do was remark that he sure had a lot of experience dropping materials out of airplanes onto farms and did he think he could do the same thing on a forest fire. He said to come back in a week.”

Ely had other things on his plate a week later, so he asked a colleague to meet Floyd and Floyd’s brother, Vance—also a pilot—at Nolta’s private airstrip near Willows. Nolta had cut a hole in the bottom of his Boeing-Stearman Model 75 Kaydet biplane and installed a 170-gallon tank with a hinged gate, a snap and a pull. Vance flew the plane over a controlled burn for demonstration. “Vance came over low and pulled the rope and put out the fire,” Ely later wrote. “The air tanker was born.”

A few months later, Vance Nolta became the first pilot to make a free-fall water drop when he assisted a crew on the Mendenhall Fire in the Mendocino National Forest on August 12, 1955. And so it began.

Ely established the Mendocino Air Tanker Squad (MATS), the first aerial tanker unit in the world, in 1956. The squad of local agriculture pilots consisted of the Nolta brothers—Floyd, Vance and Dale—Ray Varney, Frank Prentice, Lee Sherwood, Harold Hendrickson, L. H. McCurley and Warren Bullock. Except for the Nolta brothers’ Stearman and Lee Sherwood’s Tri-Pacer monoplane, the fleet of seven planes were Naval Aircraft Factory N3N-3 biplane trainers. Sherwood flew his monoplane with a Forest Service observer onboard. Later Ely recalled of these pioneers, “The local pilots were the last of the silk scarf and leather helmet boys and they would try anything.”

The MATS pilots fought 12 fires in August 1956, their first month of operation. They spent five days in September assisting with a fire near Lake Arrowhead in the San Bernardino National Forest. Because agriculture planes did not have radios until the 1957 fire season, the tanker pilots initially had to get their directions while they were on the ground taking on retardant. Although it is not clear when they first used an observation airplane, the fire prevention officer for the forest reported that the pilots were eventually directed by “a radio-equipped Cessna used as a bird dog.” That role later became known as “Drop Coo” for Drop Coordinator. The pilots “can scramble at the crackling of a spark to their planes,” said an article in the Sacramento Bee from October 1956. “Their biplanes resemble a World War I pursuit squadron as they wing to a target with liquid ‘bomb loads.’ They fly through smoke, heat and wind storms created by the blaze to drop water and chemicals from only 30 to 90 feet above flaming tree tops.” Adding to the military ambiance, pilot Hendrickson’s 11-year-old son, Gary, added nose art to his father’s airplane, which he named Mr. Mendocino. The artwork depicted Smoky the Bear in a biplane’s cockpit.

The agricultural flying season ended in June, just as the fire season began, providing many more months of work for the MATS pilots. Pilot Frank Prentice recalled that they were paid $60 an hour (around $575 an hour today). Ely also had a $4,000 budget to pay for standby time, but the pilots remained so busy earning flight pay that the standby funds remained untouched.

Word spread to state and federal forestry units that if they needed firefighting airplanes, all they had to do was call dispatcher Charlie Lafferty in Willows. Lafferty would then call the pay phone in Lee Sherwood’s hanger. An unwritten law was that no one could make lengthy calls on the pay phone during the fire season.

Lila Prentice, Frank’s wife of 71 years, remembers she had a crystal radio tuned to the Forest Service frequency. When she heard two watch towers report smoke in the same location, she would call the hanger to alert the pilots. Her husband would then notify pilot Harold Hendrickson in the neighboring hanger and they would be ready to go by the time dispatcher Lafferty called with the coordinates for the initial water drops.

Agricultural flying and aerial firefighting both require flying close to the ground, but the newly minted MATS pilots found that the similarities ended there. Quite literally, they had a baptism by fire. As Prentice recalled, firefighting required “orbiting down in the hole” (maneuvering the aircraft into deep canyons) and “the marksmanship to hit the target and to not overshoot it.” The pilots had to fly over mountains and through smoke while battling high winds and rapidly rising air currents. They flew as low as five feet above treetops and directly toward mountains, learning that the air flowing over ridges could force their airplanes down. Over time the pilots learned how to time each water release to hit the right spot while allowing them room to clear any ridges. An N3N weighs just over 2,000 pounds, so when an airplane released 1,200 pounds of water it leapt up, helping with clearance over any oncoming heights.

But the pilots and Ely discovered another challenge: evaporation. They realized that on hot days very little water actually hit the ground. The solution was to mix water with sodium calcium borate, producing a substance that not only made it to the surface but had a melting point twice as high as the 900 degrees ignition point of a forest fire. Because the white substance stuck to brush and reflected heat, the pilots dropped it on a fire’s flanks to control spread. They soon realized, though, that shortly after being dropped, the sodium calcium borate blended in with the vegetation so they could not see where they had deployed it. Borate also sterilized the soil, so it was soon phased out. The name “Borate Bombers,” however, stuck.

Harold Hendrickson’s son, Gary, joined the field in 1972 as the copilot of a Boeing B-17 aerial tanker and he later flew Grumman AF Guardians and TBM Avengers as well as Douglas DC-6s during a 40-year career. According to Gary, the Forest Service required that retardants “had to be viscous, bright colored in order to use prior drops as a reference point, still provide fireproofing up to three days after being dropped and contain fertilizer to promote regrowth.” Those requirements led to compounds such as Bentonite, a clay that swelled up and stuck better, but sometimes came down in a chunk instead of a spray. By the 1960s, the firefighters were using a retardant with diammonium phosphate.

The thicker retardants’ viscosity made them a challenge to mix and load quickly into airplanes. Ely found another local solution with Wim Lely of Lely’s Orland Manufacturing Company, who developed a device that could mix a thousand gallons of retardant and pump it into an airplane in a matter of minutes. Lely supplied his equipment to the Forest Service for years.

The MATS pilots were soon fighting blazes all over California. Some of the biggest fires they fought in their first year were in Southern California. To find their way there they would simply follow U.S. Highway 99. Often the pilots would be gone for days with no way to contact their families except through dispatcher Lafferty, on whom they could always rely to call their wives with news from the front.

Even under such basic conditions the MATS pilots made an impact. One fire boss for the 1956 McKinley Fire in the San Bernardino National Forest wrote, “The fire was crowning in the heavy brush, but the chemical drops kept knocking the fire down so that the sector team and 50 men were able to complete their line. I do not believe this would be possible without the drops.” A study done at the end of 1956 recorded that MATS assisted in 23 Forest Service fires and that aircraft were a deciding factor for controlling 14 or them and a definite factor in assisting ground crews in four more. They made no effect on another four, and were detrimental in one, when they accidentally extinguished a backfire the ground crews had set to stop a fire’s spread, causing a loss of control.

Others were experimenting with aerial firefighting around the same time. Floyd Nolta’s former Army Air Forces boss, Hollywood stunt pilot Paul Mantz, did some informal testing in 1953 and formal experiments as part of Operation Firestop in 1954. He conducted simulations at Camp Pendleton in Southern California. There he deployed sensors to measure dispersal, wind drift, effectiveness and other factors. Mantz did further tests for the California Division of Forestry, but his work did not become operational until 1958, five years after he first investigated it. In contrast, by bypassing bureaucracy, Joe Ely and Floyd Nolta had an operational aircraft ready in one week, and within a month they were already helping put out dangerous wildfires.

Following that first historic season of firefighting with adapted biplanes, larger aircraft began joining the fight, including warbirds such as Grumman TBM Avengers, Consolidated PBY Catalinas, Boeing B-17s, Grumman F7F Tigercats and other surplus military planes. When loaded with thousands of gallons of retardant, the heavier airplanes lost some maneuverability, Prentice recalled. The extreme loss of weight that came from dropping the payload did not affect the larger airplanes as much, but that also meant they did not get the same “bounce” the biplanes exploited to clear approaching ridges. TBM pilots learned to pull the airplane’s nose high while continuing level flight and let the wings pull the airplane up. Sadly, Prentice recalled, that “the mountain would happen before they gained altitude and we lost a lot of them.” The first aerial firefighter pilot to lose his life was Joseph Anthony, who crashed on August 19, 1958, making a retardant drop near Sequoia National Park while flying for Paul Mantz Air Services. Anthony was at the controls of a TBM Avenger that Mantz had used for his tests at Camp Pendleton. By 1973, 11 more TBMs crashed while firefighting, killing the pilots in all but one incident.

More pilots joined MATS in 1958 and some original pilots went on to sign contracts with the California Division of Forestry. Preferring lighter planes, Prentice bought an N3N from Florida and spent one winter assembling the airplane after it arrived in pieces lashed to a pickup truck. Prentice flew the N3N as his own personal air tanker until 1963. Floyd Nolta remained active in the flying service until his death in 1974. His legacy lives on through his invaluable contribution to the profession of aerial firefighting. The Forest Service Air Tanker unit continued to be based at the Willows-Glenn County Airport until 1982.

Joe Ely eventually retired from the Forest Service and passed away in 2006. His son, Frank, said that his father had been highly motivated to find better methods to fight fires after the devastating loss of life in the 1953 Rattlesnake Fire. He sought ways to reduce the severity of fires so that “men could get to them safely.”

Summing up the early days, Frank Prentice said, “Willows had the right combination of airplanes, pilots and high fire zones, as did other areas like the San Joaquin Valley, but only Willows had Joe Ely and Floyd Nolta.” Prentice was the last surviving member of the Mendocino Air Tanker Squad when he died on July 16, 2020. As if in tribute, dry lightning strikes a month later started numerous fires in the same area as the Rattlesnake Fire of 1953. The resulting August Complex Fire took nearly three months to contain. It was the largest fire in California history—and aerial firefighters helped battle it, following the lead of the scrappy pilots who once flew out of Willows.

Ted Atlas is a 4th-generation Californian. After a career with the Santa Clara County Sheriff’s Department, he turned his interest to writing about California history. He published his first book, Candlestick Park, in 2010. He first became aware of this story in 1986, when his brother and sister-in-law bought a house that Floyd Nolta had owned in Willows. For further reading, Atlas recommends Fire Bomber into Hell: A Story of Survival in a Deadly Occupation by Linc Alexander.