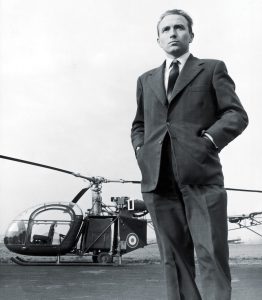

Susan Oliver conquered her fear of flying to become the second woman to pilot a single-engine airplane solo from New York to Europe.

When Susan Oliver landed her Aero Commander 200 in Copenhagen on September 28, 1967, she was treated like Hollywood royalty. Photographers, reporters and local dignitaries swarmed around her, two Scandinavian Airlines flight attendants presented her a bouquet of flowers and a Los Angeles radio host called to interview her live on-air. Like a scene out of a spy novel, though, her arrival was accompanied by a foreboding note. A representative of Aeroflot, the Soviet airline, told Oliver she had arrived too late to complete the planned final leg of her trip.

Oliver, a popular television and movie actress, was trying to become the first woman to fly from New York to Moscow. She departed LaGuardia Airport on September 21 and completed the first legs of her trip in record times. She had received permission to visit the Soviet Union, but delays for training, aircraft modifications and weather pushed her beyond her assigned arrival time. Repeated trips to the Soviet embassy made no difference: The flight was over.

Born in 1932 as Charlotte Gercke, Oliver was a well-established actress by the time of her Moscow flight attempt. She had starred in a 1957 film, The Green-Eyed Blond (although she was blue-eyed), and had guest-starred in dozens of TV episodes.

At the end of a trip to Europe in early 1959, she boarded a Pan American Boeing 707 for the return to the States. “Then somewhere over the middle of the Atlantic we suddenly went bump in the night, as if the plane had hit an air pocket, and with a sharp lunge started falling, tumbling hard,” Oliver wrote in her 1983 autobiography, Odyssey: A Daring Transatlantic Journey.

While the flight’s captain schmoozed with VIPs in the first-class cabin, the autopilot had disengaged and the copilot, who was distracted by other chores, didn’t notice. The aircraft rapidly spiraled from 35,000 to 6,000 feet before the captain made his way back to the cockpit and they recovered from the descent. Oliver returned to New York only to witness clean-up efforts near LaGuardia, where a Lockheed L-188 Electra had just crashed into the East River, killing 65 of 73 on board, and to hear that rocker Buddy Holly had died in an airplane crash that same day. She swore off aviation, passing up acting gigs that would have required her to fly.

A hypnotist helped her overcome her fear, however, and after taking a flight in a private plane above Los Angeles in early 1964, Oliver plunked down $625 for flying lessons. She soloed in October of that year, shortly before completing perhaps her best-known acting role. In the original “Star Trek” TV series pilot she played Vina, an Earth girl who assumed many forms, including a dancing green-skinned Orion slave.

After earning her private pilot’s license, Oliver worked on commercial and instrument ratings, receiving both in 1966. “Always, on film locations or publicity junkets, I’d head to the local airport,” she wrote. “My log book began filling up with places like Coonamessett, Atlantic City, Victoria, B.C., Mexico City, and Niagara Falls.”

In 1966 she placed second in the Reno Celebrity Air Race. She also survived the crash of a Piper Cub piloted by a friend. And in 1967 she decided to attempt the New York–Moscow crossing.

Oliver chose the Aero Commander 200 because she had experience with it, piloting it for an Easter Seals publicity campaign in early 1967, and because she preferred the simplicity of a single-engine aircraft. A corporate sponsor added an extra fuel tank in the back seat and new avionics for the tricky overwater flights. She stashed a life raft and an oxygen bottle aboard, studied navigation and Russian, and consulted a clairvoyant (who promised success).

Oliver trained for the flight with her boyfriend Mira Slovak, a pilot and hydroplane racer who had defected from Czechoslovakia in 1953 by hijacking the commercial DC-3 flight he was piloting. Shortly before her scheduled departure, though, he told her she wasn’t ready for such a challenge (she had recorded just 480 flight hours by the time she left New York), so they broke up. “She had the touch, she had the feelings for it, but she didn’t have any experience, and the Atlantic needs a lot of experience,” Slovak said in a 2014 documentary about Oliver, The Green Girl.

Oliver’s journey took her to Goose Bay, Canada; Narsarsuaq, Greenland; Keflavik, Iceland; and Prestwick, Scotland, before finishing in Copenhagen. In Goose Bay she stayed at an Air Force base, sleeping in the same room that had once hosted Charles Lindbergh. She faced a daunting landing and departure in Greenland, at the end of a long fjord and with a low ceiling that forced her to spiral up through the narrow chute until she was able to break through the clouds. And her wings began to ice up during the final stage of her flight to Scotland.

When Oliver arrived in Copenhagen—only the second woman to complete a solo New York-to-Europe flight—she was still hopeful of reaching Moscow. She had checked with the Soviet embassy in Washington, D.C., before the trip, and was assured there would be no problem. Yet in her two visits to the embassy in Copenhagen she wasn’t even granted an audience. “No-one in that sad, gray other country will even say why I’m not allowed to fly my pretty Bluebird into their private yard,” she wrote.

Although Oliver’s trip was over, her aviation career was not. In 1970 she won the Powder Puff Derby copiloting a Piper Comanche. She also became the first woman to train to fly the Learjet, and even flew a few charters in it.

Later, Oliver received her glider certification (and flew one in a 1973 episode of “The American Sportsman” TV series), was awarded an honorary doctorate of aeronautical science by Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University and earned her only Emmy nomination for playing one of Amelia Earhart’s instructors in a TV movie. Oliver passed her final FAA physical in 1976 and gave up flying soon after to concentrate on other endeavors, including a stab at directing. She died in 1990 at age 58 after losing a battle with cancer.

This article originally appeared in the May 2021 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe today!