When Hollywood and its hoopla encountered a new set of hoops

In 1948 a perfect storm of legal troubles and technological change combined with an economic slump to take down Old Hollywood—the storied principality of fiefdoms ruled by men who had started out in the flicker era and which by World War II’s end controlled every aspect of the motion picture business. After they had dominated popular entertainment by offering a steady diet of escapism through a depression and a global war, the eight studios that made up the American movie industry suddenly found conditions souring. Summing up the industry’s state at year’s end, New York Times reporter Thomas F. Brady wrote, “Profits are down, employment is down, morale is down.”

“Hollywood” meant the Big Five and the Little Three. Paramount, which recently had edged past Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer to take over the lead position in the Big Five, was trailed by 20th Century Fox, Warner Bros., and RKO—the smallest of what were considered the majors. The Little Three—Columbia, Universal, and United Artists—completed the roster. Lesser studios, like Disney, releasing one or two animated films a year, and Republic, with its stream of westerns starring Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, and their ilk, had virtually no impact on the overall industry profile.

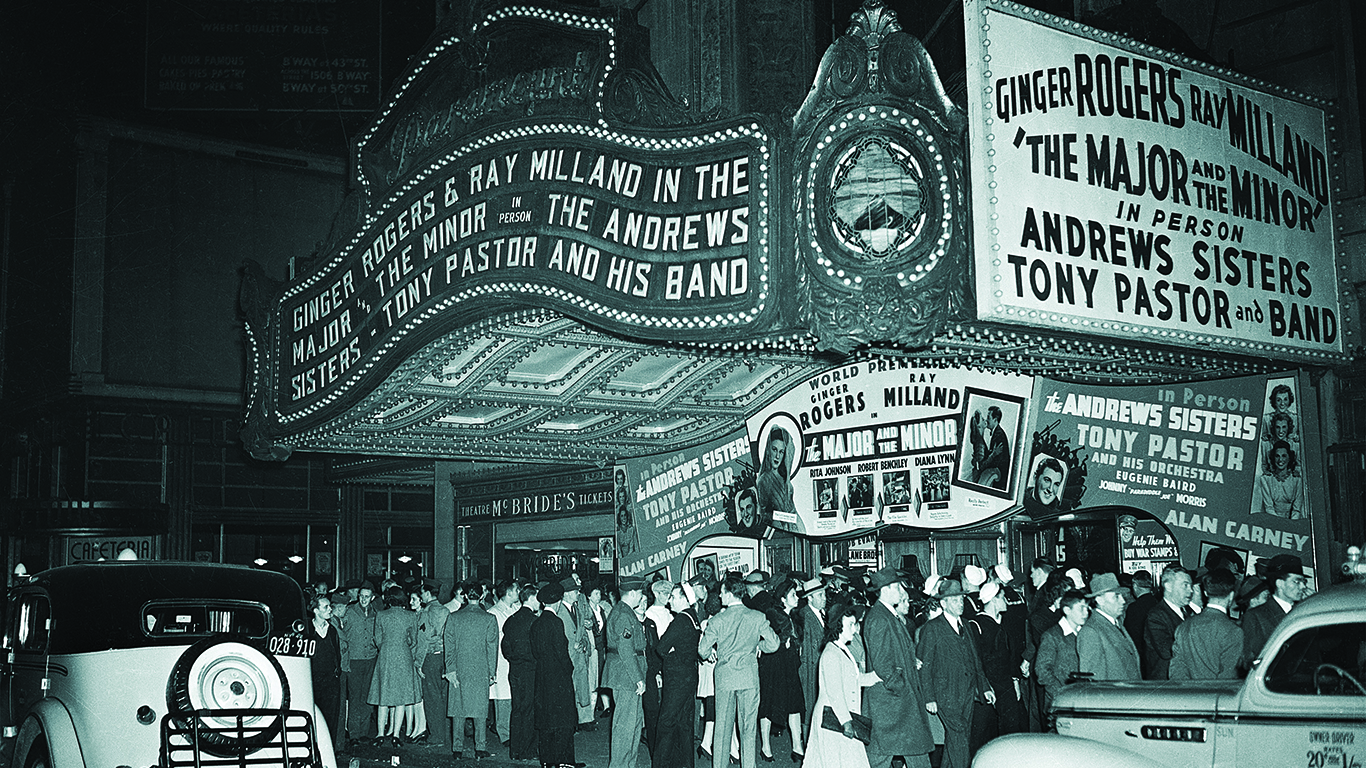

At the time movies pervaded American life as a cultural phenomenon and a pillar of the economy. Members of a typical family religiously read newspaper columns and entire magazines devoted to gossip about movie stars and at least once a week took in a film, most often on Sunday, which for most theaters represented 25 percent of weekly revenue. In 1948, Hollywood’s peak year, that habit worked out to a weekly average of 90 million paying customers spending more than $1.7 billion to buy tickets. Films accounted for more than 90 percent of Americans’ outlay on entertainment, a category that included everything from live theater and concerts to bowling and shooting pool.

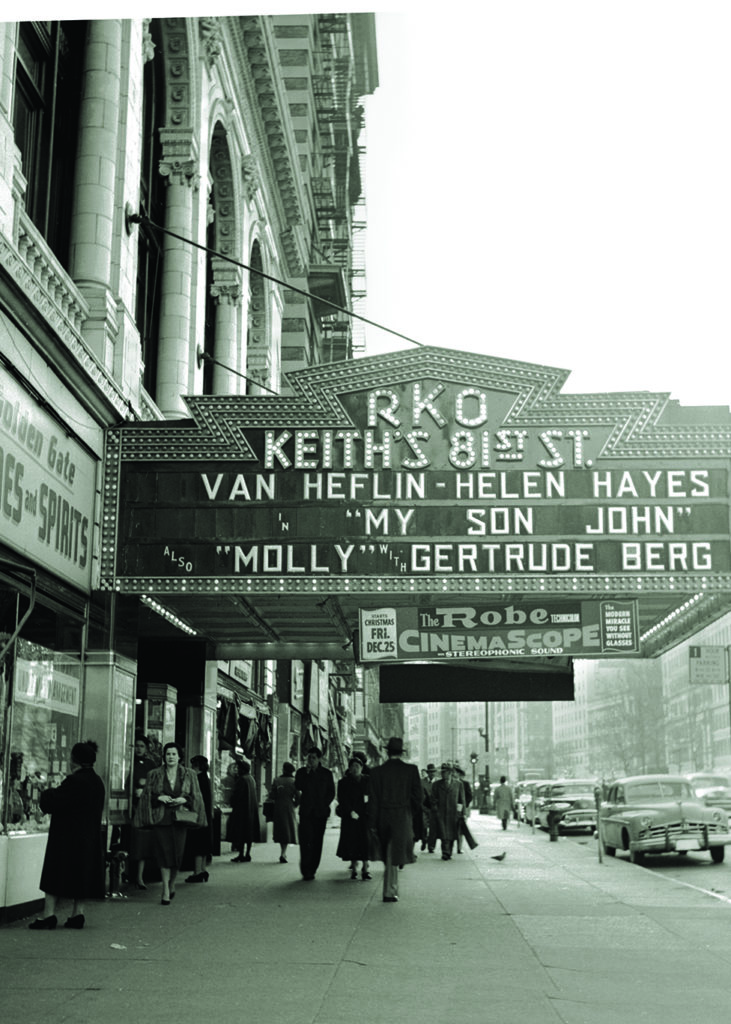

Studio moguls at the Big Five had taken care to build an economic structure in which their enterprises not only produced films but owned and ran the most prestigious major-market movie houses. Among the majors, Paramount far and away owned the most movie theaters, with 1,395. Twentieth Century Fox had 363, Warner Brothers 501, Loew’s (M-G-M) 135, and RKO 109. Studio-owned theaters comprised only 17 percent of the country’s picture houses, but they were the gems, together accounting for 45 percent of cinema ticket sales. The arrangement often relegated independently owned theaters to second-run status, with films coming to independent screens only after they had been shown at a theater with better connections. In 38 sizable American cities, the studios owned every first-run house.

The studios had the muscle to ensure that screens they did not own played their output, charging operators a slice of each ticket purchased. Key to the studios’ relationship with independent theater owners were such practices as “blind selling”—forcing indies to book films sight unseen—and “block booking”—tying access to a feature much in demand to booking a passel of studio-selected also-rans. This stipulation consigned indie theater owners to showing, usually for at least a week, dogs no one wanted to see, such as Mourning Becomes Electra. That dreary 1947 version of Eugene O’Neill’s resetting of Greek tragedy cost RKO $2.3 million to make and took in a paltry $435,000 at the box office. The studios even colluded to set ticket prices, refusing to allow theater owners to experiment at pumping up box office by offering discounts on historically slow Mondays and Tuesdays and regulating whether and when theaters could show double features or stage prize nights and other promotions.

The system’s central concept was that studios should control all levels of the industry. Studio executives believed that they alone knew what moviegoers wanted, not only at home but in Great Britain and other increasingly important overseas markets. To enforce their control, studios locked directors, writers, and actors fitting their particular visions into long-term contracts. Those contracts often ran for seven years. Top stars like Bing Crosby and Claudette Colbert might have made as much as $400,000 per annum, but had to take whatever roles their masters offered, often grinding out three shows a year. Creating as the contract structure did ensembles of personnel on both sides of the lens accustomed to working together, the system lent each studio a distinctive style: Warner’s urban gangster grit, M-G-M dramas’ rampant Anglophilia, the loose-limbed jitterbugging of Universal’s teenarama musicals. But the system also imposed moral conformity. To pacify bluestockings and fend off federal censorship, the studios composed and adhered to a detailed production code that defined subjects, images, and vocabulary to avoid.

Studios operated a host of related businesses. For instance, in addition to its movie theaters, Warner Bros. had 108 subsidiaries, including a film processing lab, recording studios, booking agencies, a manufacturer of movie house furnishings, and no fewer than ten music publishers. However, Mae D. Huettig, who in 1944 undertook the first economic analysis of the studio system, discovered that theater ownership was the true font of studio profits.

The system and its vertical integration were calling out for dismantling by federal trust busters. Hollywood’s antitrust problems came to a head in 1948 thanks in part to the industry’s earlier success at fighting off those problems.

In 1938, the U.S. Justice Department had filed a suit aimed at abolishing monopolistic practices in the motion picture industry. Goal one was forcing the studios to divest theaters they owned. However, political pressure, amplified by the twin Depression facts that the industry was sagging and that a strapped citizenry was relying on inexpensive nights at the movies as a rare distraction from glum times, softened the Justice approach. Government lawyers settled that suit by engineering a consent decree. In that deal, moviemakers made minor promises: to stop forcing theaters to book studio shorts along with studio features, to limit “block booking” packages to five pictures, and to allow independent theater owners to see films at special screenings before booking them. Another provision in the decree came to bite Hollywood: unless studios demonstrated “a satisfactory level of compliance” by November 1943, the government could reinstate its suit. The studios slacked on compliance, and the government went back to court, this time vowing to stick to its principles.

United States v. Paramount went to trial in U.S. District Court in Manhattan in October 1945. The 20-day trial resulted in a federal judgment that the studios had “unreasonably restrained trade and commerce in the distribution and exhibition of motion pictures and attempted to monopolize such trade and commerce.” Judge Henry W. Goddard ordered an end to block booking, blind selling, and minimum ticket prices and told studios not to expand their theater ownership. Judge Goddard let studios keep theaters they already held. Invoking a 1903 statute allowing antitrust cases to skip mid-level appeals courts, both government and the studios appealed the decision directly to the U.S. Supreme Court,

In their May 3, 1948, ruling, the justices upheld every restraint District Court Judge Goddard had imposed on studio film distribution. In what studios interpreted as a big victory, the High Court left intact the lower court’s finding that studios could keep their theaters. “I think the ruling means the end of the divestiture threat,” said an optimistic Joseph Schenck, chairman of 20th Century Fox. That reading may have been fanciful. The opinion, by Justice William O. Douglas, roundly criticized Judge Goddard’s reasoning on divestiture, calling his logic in refusing to order the studios to shed their theaters both “deficient” and “obscure.” The justices ordered Goddard to revisit the question—a directive whose tone strongly suggested the studios should be forced to sell their theaters.

Five months after the Supreme Court spoke, the Justice Department sent a memorandum to the Big Five—Paramount, M-G-M, Fox, Warner, and RKO—stating that the government was willing to forgo a new trial and to end the litigation with a consent decree, provided the studios agreed to separate film production and film exhibition. The studios refused.

“We have taken years to accumulate the company assets we have, and we will fight to hold on to them,” Harry M. Warner proclaimed.

That defiant unity was fleeting. Within days, maverick millionaire Howard Hughes, who had just paid $8.8 million for RKO Pictures, accepted a government deal. On November 8, 1948, Hughes signed a consent decree ending the government’s case against his studio by agreeing to sell RKO Theatres Corp.

With its 109 movie houses, RKO was a fairly minor Hollywood player but Hughes’s surrender made it apparent that cinematic vertical integration was over. All doubt evaporated in February 1949, when Paramount signed its own “divorcement” decree. At the other big studios, moguls eventually heeded lawyers’ advice that restructuring was inevitable. Warner and Fox consented to divest in 1951; M-G-M, in 1952.

Loss of their cash-cow theaters could not have hit studios at a worse time. Already in 1948, the majors had laid off around 10 percent of their 30,000 employees. Moviegoers were becoming more discriminating, sapping studio profits. Total industry domestic pre-tax income for 1948 was $110 million, down from $151 million in 1947 and $218 million in 1946. A poignant indicator: the annual Academy Awards fête in Hollywood, historically a luxe affair at the 6,300-seat Shrine Auditorium, had the forlorn air of a downscaled event in 1948, taking place in the 1,010-seat theater owned by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences.

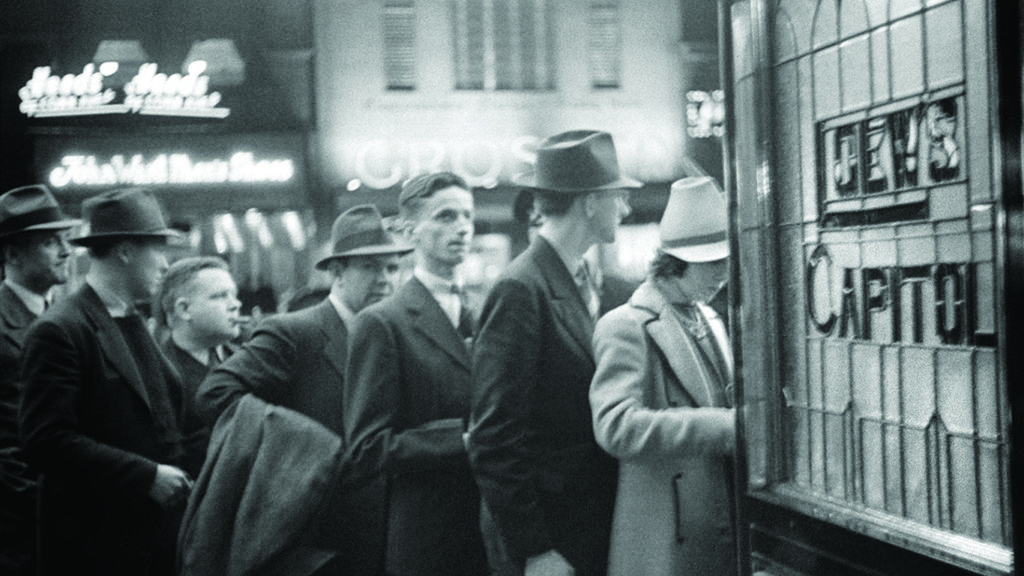

Hollywood was fishing for new profit sources amid a sea of troubles. From a boom fueled by consumer demand unleashed by peace after years of wartime rationing and shortages, the American economy suddenly slumped. Recession officially clamped down in late 1948, with GNP dropping 1.7 percent and unemployment peaking at 7.9 percent. Even folks with disposable income were clutching their greenbacks. Department store sales fell 22 percent, and an afternoon or evening at the movies was no longer a routine pleasure but an outlay undertaken warily. On an average week in 1949, 70 million Americans went to the movies—22 percent fewer than in 1948 and the fewest since 1934, the nadir of the Depression. A San Francisco theater chain reported business off 33 percent; a Philadelphia chain was down 45 percent.

Compounding the drop in domestic ticket sales, Hollywood’s overseas revenue was in a nosedive, as governments acted to ensure that scarce foreign currency went for necessities rather than frivolities. In Great Britain, American films accounted for more than 80 percent of movies shown. But in 1947 Parliament slapped a 75 percent tax on income from foreign—that is, American—films and in 1948 decreed that no more than half of the total playing time of movies in Britain could be films made outside the U.K. France joined Britain in curbing the earnings American studios could take home.

Along with having to pitch once-subservient independent theater owners on booking their films and to work to get cash-strapped consumers to buy tickets, the studios had to contend with television. Once, in the words of producer Samuel Goldwyn, “little more than a gimmick used by tavern-keepers to induce patrons to linger over another drink,” TV quickly evolved into an in-home urban luxury and then achieved ubiquity. In 1948 America reached the million-set mark, for the studios an ominous tally. In 1950, 3.8 million American homes had a TV; in 1951, 10.3 million. In 1947, American manufacturers had produced 179,000 sets; that output ballooned in 1948 to 975,000, in 1949 to 3 million, and in 1950 to 7.5 million. In 1948, television transmission began in Boston, Richmond, Atlanta, and New Orleans. In 1949, Houston’s and Miami’s first television stations went on the air, bringing the domestic station count to 77; the Federal Communications Commission had in hand 311 applications for stations. That antitrust loss proscribed movie studios from acquiring TV stations; the FCC formally announced a “strong presumption” that any business found to have been a monopolist would not be “qualified to operate a broadcast station in the public interest.”

Why should families spend shekels at the neighborhood theater to watch a routine crime drama or mildly amusing comedy when right in their living rooms they could watch Martin Kane, Private Eye and The Goldbergs and the parade of stars on Ed Sullivan’s Toast of the Town? Applicants were telling bankers they could keep up payments on loans to buy TV sets by skipping trips to the Bijou. Surveys on TV ownership’s impact on moviegoing produced wildly different results, with movie-going families reporting drops in attendance varying between 13 percent and 84 percent. Even the lower figure was “no consolation,” said Marcus Cohn, a lawyer hired by the Theatre Owners of America for advice on the TV dilemma. “The surveys were unanimous as to the trend,” Cohn warned. Starved for revenue, studios sold TV stations broadcast rights to vintage movies, strengthening the rival medium.

To survive, Hollywood had to reinvent itself, offering viewers something they could not get on the little screen. The display of the most popular mid-priced TV set measured 10 inches corner to corner; even a top-of-the-line set selling for $695 went only 15 inches diagonally. The content was of a piece. “Television is taking over the trivia,” said director Howard Hawks, implying that movies had to get better and go bigger. Goldwyn read the market the same way. “Serious producers know that only by increasing the quality of their pictures can they meet the ominous problems raised by declining box offices,” he declared.

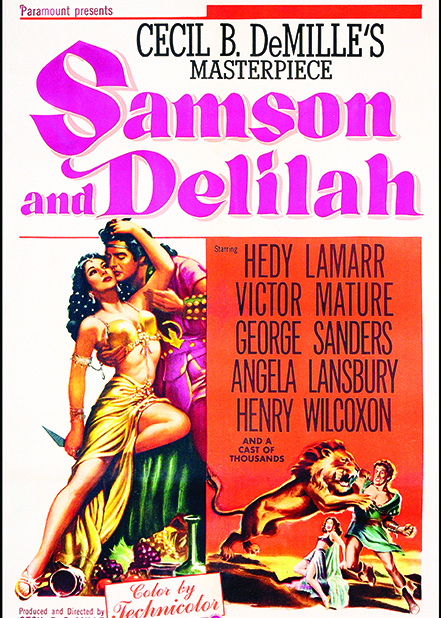

The moguls understood “quality” to mean an overwhelming opulence that made the television programming of the day look like summer stock. Cecil B. DeMille’s 1949 extravaganza Samson and Delilah embodied the gambit: yes, a leaden script delivered woodenly by Victor Mature and Hedy Lamar in the title roles, but also enormous sets, ravishing costumes, and armies of extras, all rendered in vivid Technicolor—as trade publication Boxoffice put it, “the most prodigious spectacle ever conceived.” The recipe worked, drawing stay-at-homes off the sofa and into theaters. Samson and Delilah took in $11 million at domestic box offices, well more than twice the ticket sales of that year’s No. 2 film, the M-G-M World War II epic Battleground, and more than any film had ever made except for Gone With the Wind and The Best Years of Our Lives. Samson and Delilah cost around $3 million. Hollywood followed up with such Biblical extravaganzas as 1951’s David and Bathsheba and 1956’s 3-hour-and-40-minute The Ten Commandments. But extravaganzas required advance planning and heaps of money, not a template a studio could impose on even a significant portion of its annual output.

However, pieces of the template could work. For instance, color. Color TV was a hothouse flower many years from mass adoption; all those millions of teeny sets were receiving broadcasts in black and white. Hollywood could paint the screen with a vivacity accentuating the little box’s drabness. Tactically, studios had reserved color film for musicals and historical films featuring extensive pageantry; only one feature in five was in color. The format was expensive; color film’s technical challenges added roughly 30 percent to production costs. Happily for Hollywood, the wizards of the lab and the camera were overcoming those challenges just as home television adoption was ballooning. By the early 1950s, Hollywood was filming 51 percent of its features in color.

Of course, beyond color Samson and Delilah and ilk had spectacle. Not every production was able to feature a Philistine temple collapsing, but Hollywood could wallop moviegoers with wow-inducing grandeur. The most dramatic innovation was Cinerama, designed as an immersive experience. Based on wartime aerial gunner training technology, Cinerama synchronized three 35mm projectors to deliver an image across a huge 146° arc. When the system debuted in Manhattan in 1952, The New York Times reported, “people sat back in spellbound wonder as the scenic program flowed across the screen. It was really as though most of them were seeing motion pictures for the first time.” Expensive to produce and present, Cinerama features were never going to be more than novelties. But the system did show that gigantism sold. In 1953, 20th Century Fox debuted CinemaScope, showing images 2.66 times as wide as they were high, almost double the standard boxy ratio. Paramount followed with VistaVision. A brief fad surged for films projected in overlapping images for which viewers wore special glasses to experience a three-dimensional effect.

Color, spectacle, and sex lured viewers away from TV and back into theaters, but the market clearly could absorb far fewer pictures than the volume that had sustained the studio system. In 1945, Paramount produced 25 features; a decade later, that annual total was 10. The studios began distributing films made outside the system. When RKO in 1957 sold its production facilities to TV stars Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, who intended to film their popular situation comedy on the premises, it was clear that Old Hollywood was dead. The studios gave up the control that had underpinned their style of operation. Top stars and directors freed of long-term contracts could and did negotiate project-by-project deals. As independents, popular actors coaxed studios into forking over ownership shares in their films’ profits. To star in Paramount’s 1955 To Catch a Thief, Cary Grant insisted on 10 percent of the film’s receipts. That one venture earned Grant more than $700,000, nearly double what the contract system had paid top stars to make three pictures a year.

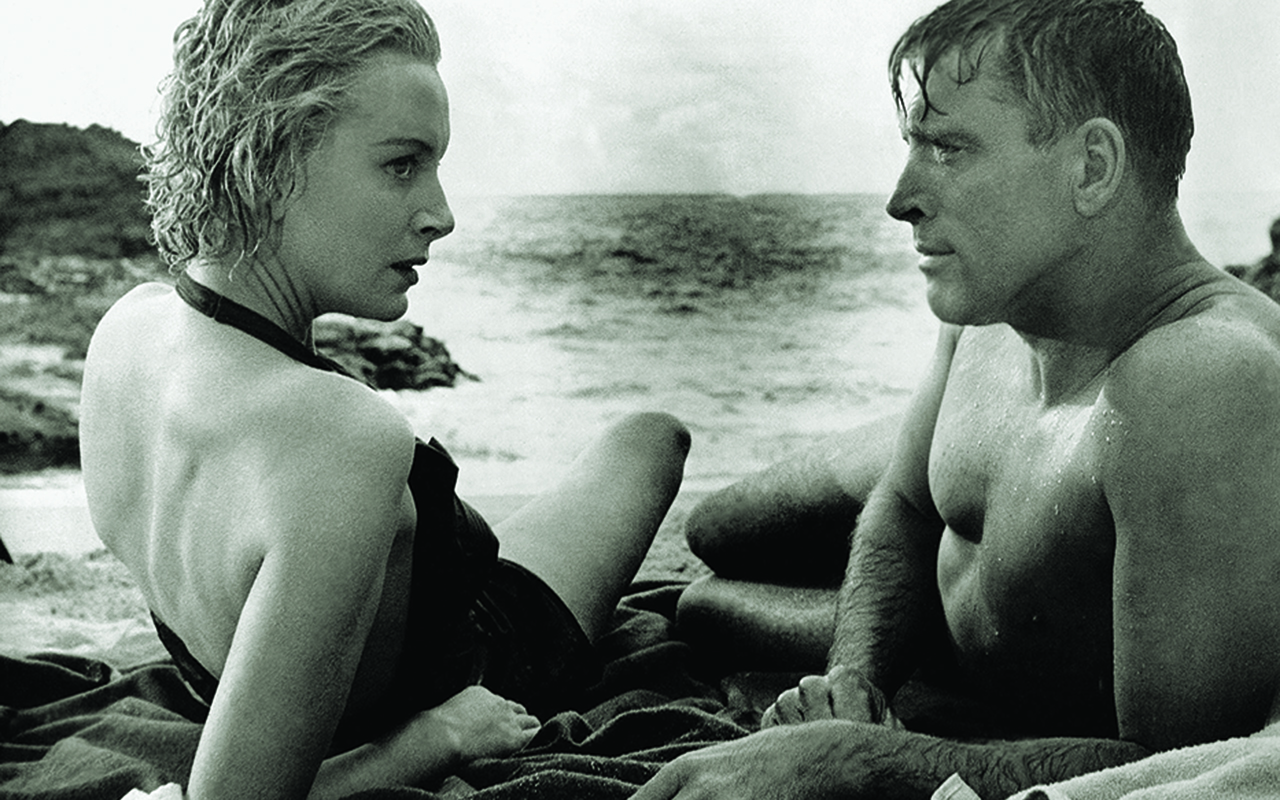

Moguls’ narrow reading of public tastes also had to go. Television was programming some intelligent and engaging dramas, but most of its schedule was family-oriented and superficial. The marketing imperative to offer at the movies content TV could not show—and a 1952 Supreme Court decision outlawing state censorship boards—led filmmakers to push for relaxation of the industry code’s taboos and enforcement got increasingly lax. An audience was waiting for A Streetcar Named Desire and From Here to Eternity and Pickup on South Street—films clearly aimed at adults looking for a measure of sex and streetwise dialogue—and Hollywood noticed.

The independence stars were exercising was mirrored among other creators. Companies formed by producers and directors offered studios limited but still potentially lucrative opportunities as distributors. As early as 1948, director Alfred Hitchcock, seeking artistic autonomy and economic muscle, established Transatlantic Pictures, shooting the murder drama Rope as if in a single take, a mold-breaking technique no studio would have stood for. Also in 1948, actor Burt Lancaster formed a production company that over 15 years produced 21 films distributed by United Artists. The list included Trapeze, whose $7.3 million North American box office take made that film the third-highest earner of 1956. An even more significant marker of the New Hollywood was the Lancaster company’s Marty, anointed best picture at the 1955 Academy Awards. This small, sweet romance about a working-class not-so-young couple starring overweight, pug-faced Ernest Borgnine was the antithesis of Old Hollywood glamour.