In the early 1930s, the United States had a crime problem. Across the Midwest, heavily armed outlaws like John Dillinger, Baby Face Nelson, Pretty Boy Floyd, Clyde Barrow, and Bonnie Parker, among hordes of less notorious characters, were robbing banks seemingly at will and in the process becoming household names. In cities, gangsters made rich and powerful by a populace fond of ignoring Prohibition emerged from that experiment’s demise in 1933 with a renewed focus on gambling, loansharking, and prostitution. Along with handguns, some hoodlums carried the .45-cal. Thompson M1921 and subsequent versions of what military armorers called “submachine guns” because they fired pistol bullets rather than the rifle rounds that machine guns fired. Able to spew slugs at the rate of hundreds per minute, a “Tommy gun” was a fearsome, if marginally accurate, weapon.

The government needed a way to curb access to these and other outlaw weapons like sawed-off shotguns but had scant power to do so. At the time, Congress enjoyed only limited authority over interstate commerce, and firearms control was seen as a matter for states to handle. The contours of the Second Amendment and the right to bear arms had not been tested. In early 1934, the U.S. Department of Justice came up with a clever approach to regulate certain types of firearm by using taxation to trap gunslinging gangsters. The resulting statute was the nation’s most comprehensive gun-control measure yet.

Firearms had been on the public agenda since the early 1900s. With more Americans living in cities and cities more congested, states re-examined the need to carry firearms. In 1911, New York imposed the Sullivan Act, requiring a resident wishing to keep a gun at home to apply for a permit to do so; the law required a separate permit to carry a concealed weapon. The act got its name from its sponsor, state Senator Timothy D. Sullivan, a famous Tammany Hall fixer. California, Pennsylvania, and other states limited carrying concealed firearms and banned sale of weapons to minors, felons, drunkards, and persons “of unsound mind.” (In April 2021, the U.S. Supreme Court announced it would review the constitutionality of these laws.)

Between the late 1800s and World War I, multiple inventors had patented systems using the mechanical energy generated by shooting a weapon to fire the succeeding round. At the pull of a trigger, machine guns could hurl a storm of lead slugs. However, the units such as manufacturers Maxim, Lewis, and Browning made were large and heavy and needed several men to haul, emplace, and operate them. As the Great War was ending, U.S. Army ordnance officer John T. Thompson perfected a portable auto-fire “trench broom” that a single doughboy could use to clear strong points. Weighing less than 10 lbs., Thompson’s 35-inch weapon featured double pistol-style grips and a shoulder stock. A drum or stick magazine held ready 20 to 100 .45-cal. rounds that were devastating at close range.

At 13 to 24 lbs. and nearly 4 feet in length, another new military weapon, the Browning Automatic Rifle, was more cumbersome than the Thompson but also fired more powerful .30-06 rifle rounds loaded in 20- and 40-round clips.

Legitimate customers could buy Thompson guns and BARs from retailers. Fanciful advertisements pitched Thompsons to civilians with a drawing of a cowboy driving off rustlers by unloading a Tommy gun at the miscreants. Patentholder Auto-Ordnance Corp. hawked the gun as the “ideal weapon for the protection of large estates, ranches, plantations, etc.” These weapons also entered the illicit distribution chain through dubious sellers and pilferage from National Guard armories.

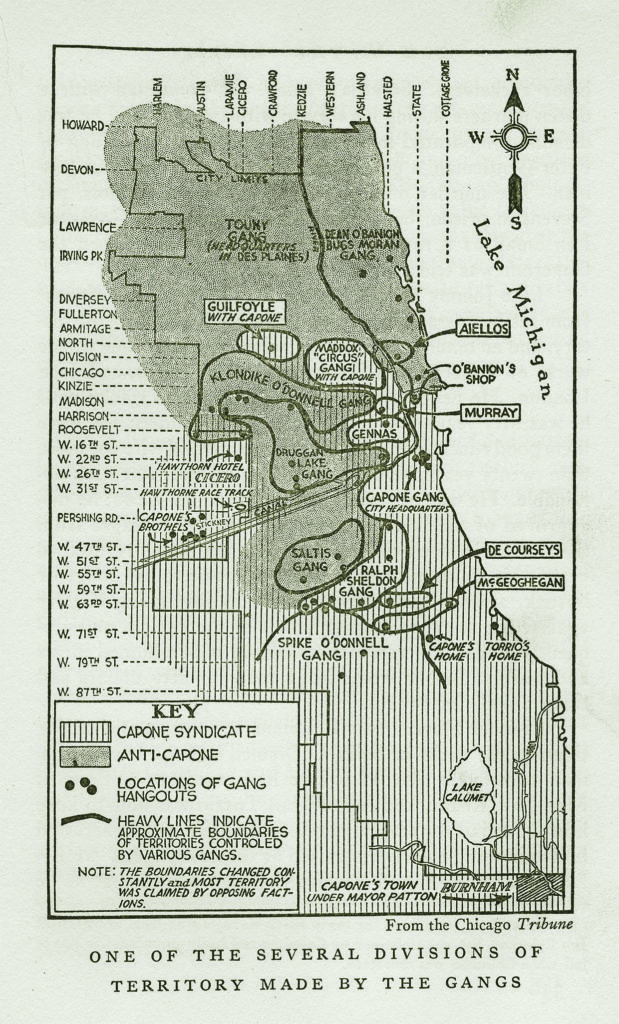

On the heels of World War I and the emergence of portable automatic weapons came Prohibition, a constitutional ban on the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages. The United States went dry on January 17, 1920. Americans still wanted to drink, however, and underworld gangs accommodated them. Bootlegging in Chicago alone tallied sales of more than $100 million yearly, with violence among competitors to match. More than 700 people died in Chicago’s beer wars. Mobsters took up the Thompson, but pistols did not go out of fashion. Individuals whom some states barred from acquiring pistols in person, such as convicted criminals, could buy handguns easily by mail, spurring Congress to pass the largely symbolic 1927 Mailing of Firearms Act. That law forbade shipping handguns via the U.S. Postal Service but did not apply to shipments by private express companies. To a degree individual states—Massachusetts, West Virginia, Michigan, New Jersey, and Missouri—regulated firearms purchases, usually by barring individuals such as convicted criminals from buying pistols. Under these rules a prospective buyer often had to state that he or she was not prohibited from buying a pistol, based on the perhaps unrealistic belief that someone in a prohibited class would not buy a pistol for fear of being caught and prosecuted for making a false statement.

The night of Thursday, February 14, 1929, four men burst into SMC Cartage, a garage on North Clark Street in Chicago, Illinois. Two visitors wore police uniforms; two carried Thompsons. All were working for crime boss Alphonse Capone. SMC was an outpost of Capone rival Bugsy Moran. Capone’s men lined up seven Moran men and opened fire, leaving a calling card of corpses and 70 .45-cal. shell casings. The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre made headlines nationwide.

Also modernizing crime: the automobile, which enabled crooks to outrun police. Bandits, some lugging Thompsons or BARs, learned to hit banks and cross state lines, jumping jurisdictions in the style of robbers like Clyde Barrow, whose weapon of choice was the BAR, and accomplice Bonnie Parker. In 1932, robberies by Barrow and Parker left 13 dead. In September 1933, John Dillinger, who favored the Tommy gun, led his gang on a 10-month string of robberies that killed 10 across the heartland. With home and farm foreclosures rampant—nearly 1,000 per day in 1933—some Americans saw robbers in milder light than bankers. “And as through your life you travel/yes, as through your life you roam,” balladeer Woody Guthrie sang in “Pretty Boy Floyd.” “You won’t ever see an outlaw/drive a family from their home.” Gangster movies featured gunplay with Thompsons, despite the reality that relatively few submachine guns were loose in the land. That reality did include murderous spasms.

On June 17, 1933, agents from the U.S. Justice Department Division of Investigation, later the Federal Bureau of Investigation, entered Kansas City’s Union Station, bound 30-some miles north. The agents were escorting Frank Nash to the federal prison at Leavenworth. Nash, recently recaptured after escaping that penitentiary in 1930, six years into a 25-year sentence for mail robbery, had been running with Pretty Boy Floyd. At the train station, Floyd and two accomplices ambushed the agents escorting Nash. Rounds from a Thompson left Nash and federal agent Raymond J. Caffrey dead. The attackers escaped. On April 22, 1934, state policemen and federal agents tracked John Dillinger to a lodge in northern Wisconsin and staged a surprise raid. Dillinger and Lester “Baby Face Nelson” Gillis shot their way out with Thompsons and handguns, on the way murdering federal agent W. Carter Baum.

These and multiple other violent crimes reverberated powerfully. President Franklin D. Roosevelt vowed to spare no effort to “bring to book every law breaker, big and little.” He argued for a federal gun control statute to override the vagaries of state oversight. “[W]hat is the use of making it difficult in New York to get firearms if the gunman can go over to Connecticut or New Jersey and get all he wants?” FDR asked.

Roosevelt’s point man on crime was U.S. Attorney General Homer S. Cummings. The former Democratic National Committee chairman had worked diligently to put Roosevelt into office in 1932, and as a reward for his ardor was to be appointed governor-general of the Philippines. When the president’s nominee for attorney general suddenly died, Cummings stepped into the top Justice Department slot—temporarily, he thought. He stayed until 1939.

In 1934, Congress passed 20 administration-backed crime bills. In a first, Division of Investigation agents now could make arrests and carry firearms. The laws’ new categories of federal offenses made the Justice Department and the Division of Investigation major players in the fight against crime. Robbing a federally insured bank became a federal crime, as did crossing a state line to avoid prosecution and interfering with or killing a federal agent. But while Cummings estimated more than 500,000 criminals were “armed to the teeth,” there still was no federal curb on firearms.

In 1934, Cummings forwarded a gun control plan to Congress. He proposed a $200 tax—today, nearly $4,000—when a machine gun changed hands. At retail, a Thompson ranged in price between $175 and $227; the federal tax presumably would price it out of the legitimate market and leave a paper trail of ownership should the weapon see illegal use.

As part of the tax scheme, Cummings proposed registering machine guns. At sale or transfer, the new owner would have to give the Internal Revenue Service the weapon’s serial number and the new owner’s photograph and fingerprints. Owners whose possession of automatic weapons predated the regulation would have 60 days to register. Failure to register would risk a five-year federal prison term and a $2,000 fine, as would possession of an unregistered machine gun.

The proposal avoided the pitfalls that an outright ban posed. “[I]f we made a statute absolutely forbidding any human being to have a machine gun, you might say there is some constitutional question involved,” Cummings said. Framing the control mechanism as a tax, he said, “you are easily within the law.” The tax tack outmaneuvered criminal law’s limitations. Federal taxation authority underpinned the 1914 Harrison Act, a foundational federal narcotics statute implemented to restrict access to opium, cocaine, and other drugs, on an international migratory fowl treaty. The U.S. Supreme Court had upheld the drug law. Tax law could reach areas the ordinary criminal law could not, as in 1931, when federal tax violations tripped up once-untouchable gangland boss Al Capone.

Cummings nominally characterized his proposal in terms of revenue—enactment would bring $100,000 yearly into the federal coffers, he estimated—but he really meant to box in gangsters and outlaws. “I do not expect criminals to comply with this law; I do not expect the underworld to be going around giving their fingerprints and getting permits,” he told Congress. “But I want to be in a position, when I find such a person, to convict him because he has not complied.” An unregistered machine gun was a federal charge waiting to be brought. Gangsters “will not be able to put up vague alibis and the usual ruses, but…it will be a simple method to put them behind the bars,” said Assistant Attorney General Joseph B. Keenan. The trap had additional snares. By 1934, Texas and 27 other states had banned private ownership of machine guns. A person in any of those jurisdictions registering a machine gun with the federal government might face state criminal charges for possession of that weapon.

On April 11, 1934, Representative Hatton W. Sumners (D-Texas) introduced Cummings’s plan in the House. Not everyone was on board. Cummings’s bill overreached, some legislators said.

Besides machine guns, H.R. 9066 covered pistols, revolvers, and “any other firearm capable of being concealed on the person.” Cummings saw handguns as essential to the bill, believing a machine gun-only measure would be a halfway gesture, and the numbers supported him. Goons owned only a few hundred machine guns but had thousands of handguns, routinely concealed in waistbands and shoulder holsters. Under the bill, each handgun transfer would incur a $1 tax, and every buyer or existing owner of a pistol or revolver would have to register it.

Sportsmen’s groups and gun clubs vigorously opposed registering pistols. Gun owners’ main voice of advocacy was the National Rifle Association, a 250,000-member entity at the time so obscure that The New York Times, confusing the group with its monthly publication, American Rifleman, at first called it the “American Riflemen’s Association.” (The NRA dated to 1871, when, with the goal of improving marksmanship and responsible gun ownership, two Union veterans formed the organization.) Adding to the confusion, the public associated the initials NRA with the National Recovery Administration, a controversial pillar of the New Deal. Cummings stood firm. “Show me the man who does not want his gun registered,” he said, “and I will show you a man who should not have a gun.”

NRA figures hammered Congress in good guy/bad guy performances at hearings by the House Ways and Means Committee and the Senate Commerce Committee. The good guy was NRA President Karl T. Frederick, who projected smooth reasonableness. The Harvard-educated lawyer, 53, had won three gold medals for shooting in the 1920 Olympics and was popular among conservationists for his efforts to preserve New York’s Adirondack Mountains as a wilderness reserve. The bad guy was NRA executive vice president Milton A. Reckord, 54, a combat veteran of World War I and adjutant general of the Maryland National Guard.

“I have never believed in the general practice of carrying weapons,” Frederick told House members. “I do not believe in the general promiscuous toting of guns. I think it should be sharply restricted.” But policing crime by forcing law-abiding citizens to register pistols was overkill, he said. “I do not believe that we should burn down the barn in order to destroy the rats.”

Reckord was more strident. “[A] pistol or revolver is not dangerous; it is only dangerous in the hands of the crook,” he said. “Honest citizens…won’t obey [a pistol-registration requirement] and you are going to legislate 15 million sportsmen into criminals…with the stroke of the President’s pen.” If the administration excised handguns from the bill, the NRA vowed to lend its wholehearted support.

Gun advocates feared H.R. 9066 was only a first step. Hunting magazine Field and Stream called the bill part of an effort “to ultimately deny all citizens the right to possess firearms of any kind and for any purpose.” The NRA warned of “disarmament by subterfuge.” Senator Royal S. Copeland (D-New York), a staunch supporter of pistol registration, called these claims absurd. His own son owned many handguns, Copeland noted, and “[i]f I were to fix it so he could not have a pistol, before they were taken away from him he would fill me full of lead, I think…”

Assistant Attorney General Keenan reassured gun owners. “[T]here are not going to be snooping squads going around from house to house to see who does and who does not possess arms,” Keenan promised.

The NRA rallied members in press releases raising the specter of “dictatorial” control under which a law-abiding gun owner would be “fingerprinted and photographed for the Federal rogues’ gallery every time he buys or sells a gun of any description.”

Support for the legislation came from the General Federation of Women’s Groups—“clubwomen,” The New York Times called the organization’s membership. The federation complained that any bill that excluded pistols and revolvers would be “a joke” but also denied any desire to “remove the rights of any honest man to legitimate protection.” FDR was silent. The congressional rumpus attracted scant press attention, and at Roosevelt’s press conferences reporters ignored the subject.

H.R. 9066 failed. On May 23, 1934, Rep. Robert L. Doughton (D-North Carolina) introduced a kindred bill, H.R. 97401, which expressly exempted pistols and revolvers. Doughton’s bill covered machine guns, defined as any firearm able to fire more than one shot with a single trigger pull. Doughton also went after sawed-off shotguns—that is, any rifle or shotgun with a barrel less than 18 inches long—and silencers. A $200 yearly tax would apply to firearms dealers selling machine guns. With little debate, the House passed Doughton’s bill on June 13, 1934; the Senate followed suit five days later. Roosevelt signed the bill on June 26, 1934.

As a revenue source, the Firearms Act misfired. In 1935, the U.S. Treasury took in $8,015 in related fees; the next year, $5,342, far less than the $100,000 per year that Cummings had predicted. Not one civilian purchase of a machine gun was recorded in 1934, but gun owners registered 15,791 weapons acquired earlier. Many were short-barreled antiques that fit the definition of a sawed-off shotgun. In 1934-36, 54 persons were charged under the act. The Supreme Court upheld the taxation portion of the statute in 1937 and the registration provisions in 1939.

The first American prosecuted under the act was Miami, Florida, hotel manager Joseph H. Adams. In September 1934, a gangster pal handed Adams, 39, an unregistered Browning Automatic Rifle for safekeeping. Adams hid the gun in a golf bag in his office. He later handed off the BAR, serial number defaced, to a sketchy friend. That party tried to sell it under the table for $150, the government alleged.

Federal agents seized the weapon on January 22, 1935, and charged Adams with unlawfully transferring an unregistered machine gun. Adams’s lawyers challenged the arrest on constitutional grounds. The justices declined, saying, “The Constitution does not grant the privilege to racketeers and desperadoes to carry weapons of the character dealt with in the act.” No further record of the case could be located.

Aggressive policing, not the National Firearms Act, brought down Thompson- and BAR-toting outlaws. On May 23, 1934, sheriff’s deputies ambushed Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow near Sailes, Louisiana, killing both. That July 22, federal agents gunned down John Dillinger as he was leaving the Biograph Theater in Chicago. In October, Pretty Boy Floyd met his end near East Liverpool, Ohio, in a shootout with federal agents and police. On November 27, 1934, federal agents killed Baby Face Nelson near Barrington, Illinois, in a firefight that cost two agents their lives. Urban gangsters, realizing gunplay attracted publicity and police attention, took their operations underground.

World War II was the Thompson’s heyday, with Auto-Ordnance making more than 1.7 million units, most for the U.S. military but also for Allied forces. Thompsons saw action from Bataan to North Africa to Normandy to Okinawa. Thompsons shipped to China were used against GIs in Korea and Vietnam. Eventually the U.S. military abandoned the Thompson for the more modern M-14 and M-16 rifles and subsequent auto-fire models.

of the Division of Investigation; unidentified; Assistant Attorney General Joseph Keenan. (Everett Collection/Alamy Stock Photo) (Everett Collection/Alamy Stock Photo)

Revisiting the National Firearms Act in 1968, the Supreme Court invalidated that legislation’s registration requirements. The reason was not the right to bear arms or the commerce clause, but the Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination. By this time, many states had banned possession of machine guns and sawed-off shotguns, meanwhile outlawing possession of firearms by felons. A felon or a person in any of those states who obeyed the law and registered a prohibited weapon was admitting tacitly to committing a crime, the court ruled. The trap U.S. Attorney Homer Cummings had set for gangsters and outlaws 34 years earlier had caught the government, and later that year, Congress eliminated the act’s registration requirements.