The North gets timely help from inside sources

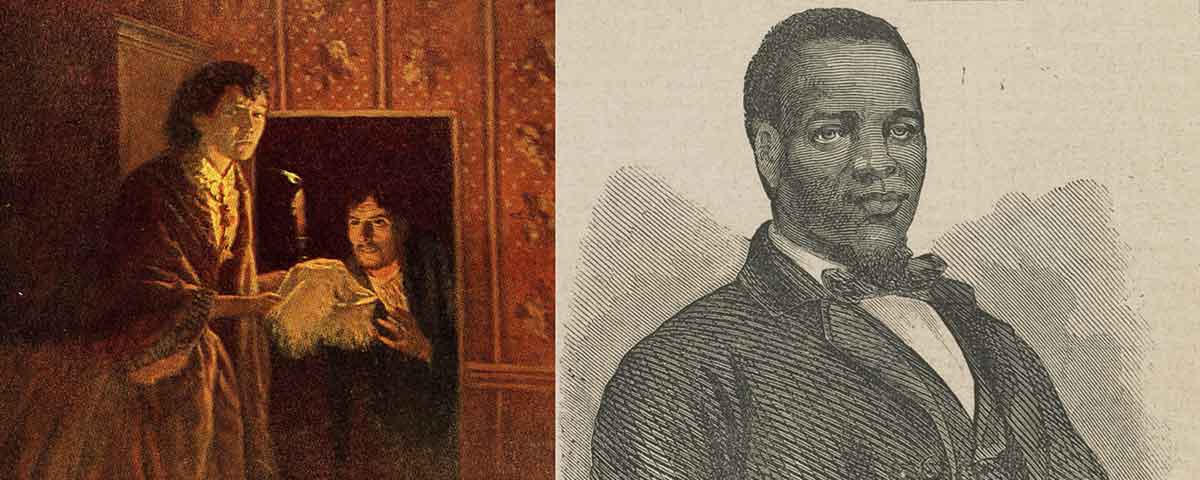

In the best of cases, a wartime spy’s prospects for a long life are not ideal. And when you are spying for the Union from within the home of the president of the Confederacy, the odds of dying young increase dramatically. Yet two slaves in the service of Jefferson Davis himself—William A. Jackson and Mary Elizabeth Bowser—provided vital information to the Union and lived to tell about it.

William Jackson’s master had reportedly hired him out to work in a Richmond restaurant prior to his being assigned the dual role of being Davis’ house servant and coachman. Ironically, it was Jackson’s color and social station that allowed him to move about with impunity whenever political and strategic meetings were being held at the Confederate White House. Writes historian Ken Dagler: “Because of his role as a menial servant, he simply was ignored. So Jefferson Davis would hold conversations with military and Confederate civilian officials in his presence.”

In May 1862—more than a year after the firing on Fort Sumter—the 30-year-old Jackson left his wife and three children in slavery and escaped to Union lines, taking with him in-depth verbal accounts of the goings-on within the Southern capital. Reportedly, he was immediately interviewed by a number of general officers, and Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell himself telegraphed the results of his “debriefing” of Jackson to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton.

Jackson’s stories were picked up by many of the North’s foremost periodicals, portraying him with both veneration and the racial condescension so common to the period. Harper’s Weekly printed a portrait of Jackson above his flowery signature, describing him as “an extremely intelligent man, [who] reads and writes…and converses in a manner which shows that he has been used to good society.” The New York Tribune also paid grudging homage to Jackson’s mental alacrity, though coupling it with a de rigueur racial slur: “The old plea that a mulatto may have a soul and be intelligent on account of the white blood in his veins, while a pure negro is nothing but an overgrown monkey minus the caudal appendage, will not hold true in this instance. Jackson is as black as a Congo negro, and much more intelligent than a good many white folks.”

Although the vital military information that Jackson passed along to the U.S. War Department was understandably kept under wraps by Stanton and his staff, his personal observations of the president and Mrs. Davis—which often amounted to juicy “insider” gossip—kept the North’s readership rapt. Jackson reported he spent considerable time driving Varina Davis around Richmond, claiming she was perpetually gloomy about the South’s prospects and often referred to the Confederacy as “about played out.” Though “Mr. Davis treated me well,” he said, “Mrs. Davis is the devil.”

According to Jackson, the president was “pale and haggard,” a poor eater, and a near-insomniac who constantly demeaned his commanders. He was “much disheartened and querulous,” Jackson reported, “fond of complaining of the want of popular support, and very downhearted about the future.” The citizens of Richmond were also suffering from steadily declining morale, Jackson insisted, and many white as well as black residents were looking forward to a Yankee takeover.

Though Jackson bolted to the North just a year after the war began, Mary Bowser remained a dedicated agent for the Union, putting her life on the line every day for nearly four years.

Bowser was born a slave about 1839, on John Van Lew’s Virginia plantation. When Van Lew died, his wife and daughter, Elizabeth, freed all the family slaves. According to some of her biographers, Elizabeth, though the daughter of a dedicated slave owner, was herself a Quaker and a staunch abolitionist. She sent the bright young Mary, who was now working as a paid servant in the Van Lew house, to Philadelphia’s Quaker School for Negroes. Upon graduation, Mary returned to Richmond and, in 1861, married a free black, Wilson Bowser.

Drawing inspiration from her close friend Elizabeth, who had formed her own extensive spy network for the Union, Mary—using an alias and affecting a dull wit but a willingness to work—procured a job as a servant to Varina Davis within the Confederate White House. Mary’s education had enabled her to read sensitive documents without arousing suspicion, and although President Davis himself ultimately became aware of a “leak” within his household, he did not suspect Mary.

Mary was able to communicate her vital intelligence via a local baker. According to the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, Thomas McNiven was “Richmond’s formal spymaster,” and on his daily trips to the Davis house, he would receive important information from Mary. As McNiven later allegedly told his daughter, “Bowser was the source of the most crucial information available, as she was working right in the Davis home and had a photographic mind. Everything she saw on the Rebel president’s desk, she could repeat word for word.”

By January 1865, Mary had in fact fallen under suspicion, and fled Davis’ home—and Richmond itself. According to several sources, as her last act before taking flight, she attempted unsuccessfully to burn down the Confederate White House.

As with Jackson, Bowser left no trail after the war. The U.S. government, in attempting to shield former agents from Southern retribution, destroyed their records, including those of Bowser and McNiven. Family tradition states that Bowser had kept a journal of her wartime activities, but descendants inadvertently disposed of it in the 1950s. In 1995, however, she was inducted into the U.S. Army Military Intelligence Corps Hall of Fame, in recognition of her Civil War contributions.

Mary Bowser was courageous and effective, but she was far from unique. As the Hutchins Center observes, “Bowser is among a number of African American women spies who worked on the Union side during the Civil War. Given the nature of the profession, we may never know how many women engaged in undercover spy operations, both planned and unplanned.”

Ron Soodalter, a regular contributor to America’s Civil War, writes from Cold Spring, N.Y.