[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he president is medically unable to do the job, a fact those closest to the leader conceal. The president insists everything is fine, but everything is not, and prospects for recovery are poor. The Hill and the media are starting to suspect the worst. It’s only a scenario, but it’s a scenario out of a national nightmare.

The Constitution, as enacted, provided only that, in case of a president’s “Death, Resignation, or Inability to discharge the Powers and Duties of the said Office,” the vice president was to take over. If neither president nor vice president could serve, the next in line was to be set by statute, the Presidential Succession Act. For 180 years, this sparse phrasing raised as many questions as it answered—and always under duress.

On April 4, 1841, a month into office, President William Henry Harrison died of pneumonia. Vice President John Tyler took the reins. Some, such as former President John Quincy Adams and Harrison’s cabinet, thought Tyler should be considered acting president, but Tyler disagreed and asserted himself to be the president.

Senator William Allen (D-Ohio) thought the distinction between president and acting president crucial. In an instance of temporary disability, Allen argued, an incumbent who recovered could take back the office from an acting president, but not from a president. If a recovered incumbent attempted to resume office, “the most fearful convulsions might follow,” Allen warned. Death being permanent, Congress brushed off the distinction and recognized Tyler as president. Wags called him “His Accidency.”

The original draft of the Constitution allowed a vice president to act temporarily as president “until the disability of the President be removed.” The Convention’s Committee on Style, whose five members included Alexander Hamilton and James Madison, lacked authority to make substantive changes, but inexplicably cut this provision.

Orderly successions followed the deaths of Zachary Taylor in 1850 and of Abraham Lincoln in 1865, but James Garfield’s 1881 shooting became the first instance of a disabled president.

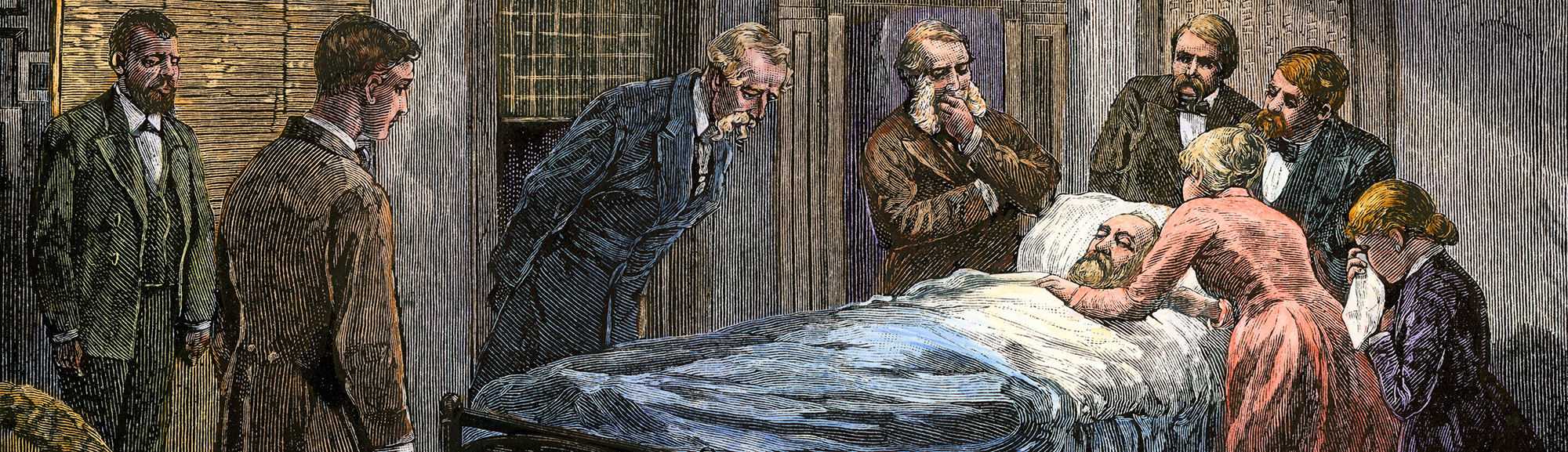

On July 2, 1881, Garfield was leaving the capital for vacation when a lunatic wounded him. Garfield seemed poised to recover, and historians believe he would have but for unsterile probing of his wounds “by every doctor who entered the sickroom and thought he could do a better job than the one before,” wrote Dr. T. Burton Smith, a medical historian. For two months, Garfield was conscious but unable to work. His only official act was to sign an extradition document. An infection killed him on September 19, 1881.

While Garfield still lived, Vice President Chester A. Arthur did not take over. Most of Garfield’s cabinet believed that doing

so would make Arthur president, not acting president. During those agonizing months, Arthur never met with Garfield.

A separate crisis arose upon Garfield’s death. Under the succession act, the next—and only—individuals in line were the president pro tem of the Senate and the speaker of the House. At the time, both positions were vacant, raising the question of who would serve if anything befell Arthur. In 1886, Congress extended the succession list.

On September 6, 1901, President William McKinley was at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, when an anarchist shot him. McKinley’s prospects seemed good and there was no pressing national business, so not only did Vice President Theodore Roosevelt not take over, Roosevelt proceeded on a planned hunting trip in New York’s Adirondack Mountains. When McKinley worsened and died on September 14, 1901, authorities scrambled to locate his successor.

These jolts presaged America’s gravest presidential incapacitation: the permanent disability of a president who refused to step aside (for the full story, see “Big Lie,” in our June 2017 issue).

The Wilson episode should have prompted legislative action on succession, but none occurred until the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Successor Lyndon B. Johnson called the avoidance of a succession disaster to date (in November 1963) “more the result of Providence than of any prudence on our part.” Senator Kenneth B. Keating (R-New York) asserted that disability and succession “have loomed as the most serious single threat to the stability and continuity of the American Presidency as an institution.” Many Americans agreed.

On January 6, 1965, Senator Birch Bayh (D-Indiana) introduced a joint resolution that became the basis of the 25th Amendment to the Constitution. Within six months, Bayh’s measure had cleared Congress; the amendment became law on February 10, 1967. “It’s a happy day,” said Bayh. “A constitutional gap that has existed for almost two centuries has finally been filled.”

The 25th Amendment authorizes a president, with congressional approval, to appoint a vice president—a vacancy that has occurred when a vice president has succeeded a dead president, when seven vice presidents have died in office, and when, in 1832, Vice President John C. Calhoun resigned. The amendment also addresses situations akin to Garfield’s and overrides the Tyler precedent by allowing a president to declare himself disabled, with the vice president standing in temporarily and the chief executive resuming office upon recovering.

The most fraught provision—known as “the nuclear option”—authorizes forced removal of a president incapacitated but unwilling or unable to admit it. If the vice president and a majority of the cabinet declare in writing that the president “is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office,” the vice president becomes acting president until the president recovers. If the president disputes that joint declaration, Congress decides if the president is disabled.

Congress picked the vice president and cabinet to make the initial decision because, the Senate Judiciary Committee believed, those are the officials closest to the president “both politically and physically.” Skeptics like Rep. William M. Colmer (D-Mississippi) feared a coup by a collusive vice president and cabinet. Sen. Robert F. Kennedy (D-New York) wondered what would happen if a president dismissed his cabinet to avoid being declared disabled. The Judiciary Committee refused to “assume hypothetical cases in which most of the parties are rogues,” choosing to believe that “we shall always be dealing with ‘reasonable men’ at the highest government level.”

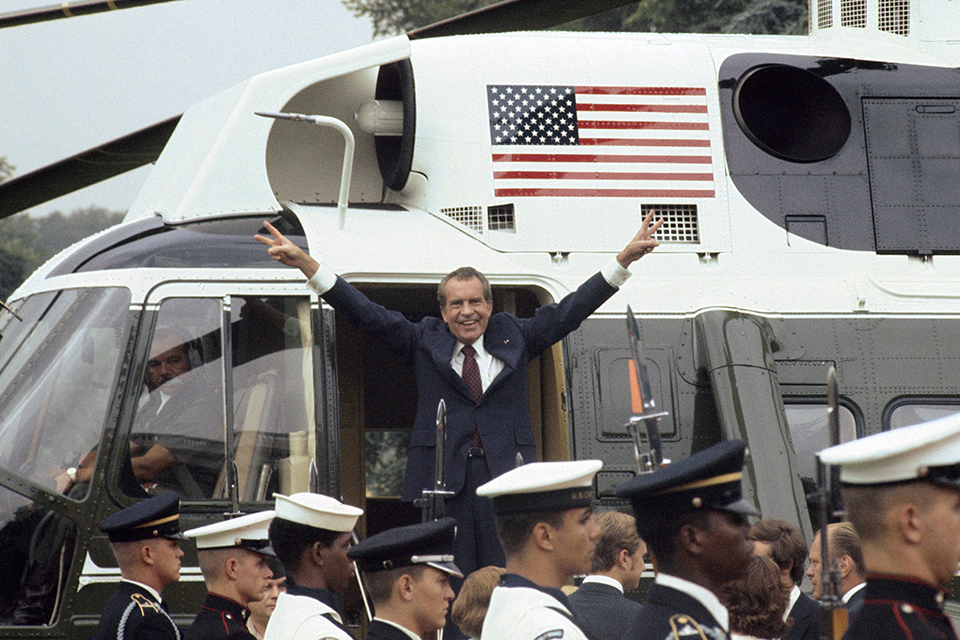

In October 1973, the 25th Amendment came into play when federal corruption charges led Vice President Spiro T. Agnew to resign. To replace Agnew, President Nixon named Rep. Gerald Ford (R-Michigan). When, on August 9, 1974, amid the Watergate scandal, Nixon resigned, Ford became president.

Several presidents, at least implicitly, have activated the voluntary-removal clause. On July 13, 1985, President Ronald Reagan underwent colon surgery; for eight hours, Reagan authorized Vice President George H.W. Bush to act in his stead. Reagan did not expressly invoke the amendment because he did not believe it applied to “such brief and temporary periods of incapacity,” but the effect was the same.

Reagan’s analysis shows a gap in the Constitution. Nothing in that document defines when disability requires a transfer of power. Observers noted this as early as 1787, when delegate John Dickinson of Delaware raised the matter at the Constitutional Convention. In 1965, Congress left the gap alone because, said Rep. Richard H. Poff (R-Virginia), a definition could lead to “a rigidity which, in application, might sometimes be unrealistic.” Rep. Edward Hutchinson (R-Michigan) disagreed. Lacking a definition, a cowardly president facing an unpopular decision could step aside, claiming an unspecified disability, and resume office after the vice president made—and took flak for—that decision, Hutchinson argued. The concept might be broad enough to allow a president facing legal trouble to step aside temporarily, a move the White House briefly considered in 1974,when Nixon was facing impeachment and a Senate trial.

Including Reagan’s polyp removal, since 1985 presidents have invoked the amendment for medical procedures three times, with sedation the key factor. President George W. Bush invoked the 25th Amendment when doctors sedated him for a July 29, 2002, colonoscopy, and again for a July 31, 2007, polyp removal. President Bill Clinton did not transfer power during a March 14, 1997, knee surgery involving local anesthesia.

No government has invoked the involuntary-removal provision, which has loomed several times. In Nixon’s final days in office, he was seen walking the White House halls by night speaking to paintings of predecessors. Aides, fearing a suicide attempt, kept tranquilizers and other medications away from him.

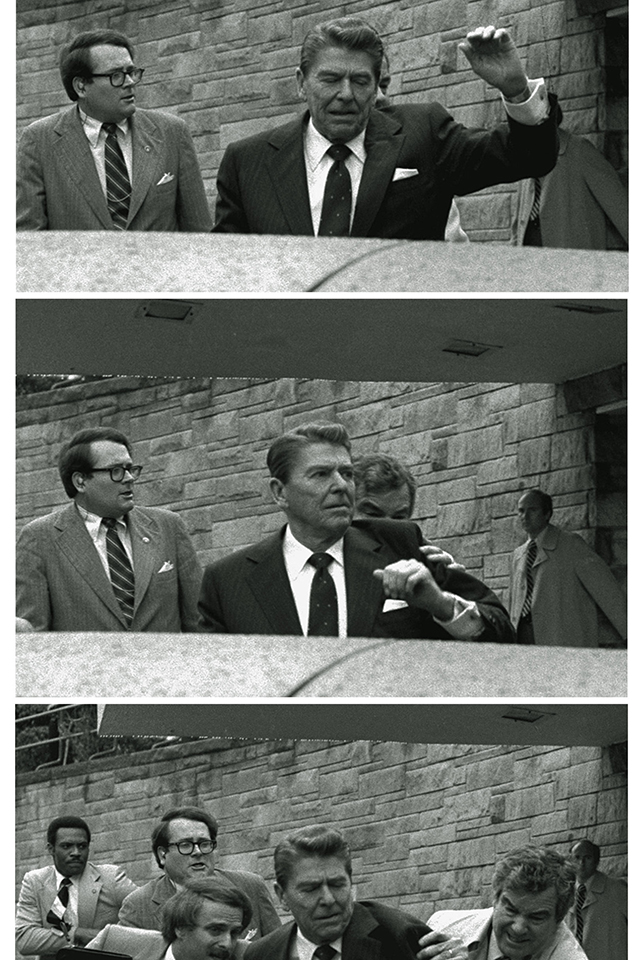

The closest call came on March 30, 1981, when a gunman shot Reagan in the capital. Rushed into surgery with no chance to turn over power to Vice President Bush, Reagan was bleeding internally and in shock, his prospects unclear. “We were uncertain about what lay ahead,” said Chris Hicks, an associate White House counsel. “We might have a dead president, or worse, a comatose one.” When White House Counsel Fred F. Fielding mentioned the 25th Amendment, he said later, he saw “eyes glazing over in some parts of the Cabinet. They didn’t even know about the 25th Amendment.” In the executive mansion, Secretary of State Alexander Haig Jr., announced—incorrectly—“As of now, I am in control here in the White House, pending return of the vice president.” Vice President George Bush was more circumspect. Flying back to Washington from Austin, Texas, Bush heard that his air crew had been told to set their helicopter down on the South Lawn of the White House. He countermanded that order. “Only the president lands on the South Lawn,” Bush explained.

Fielding did prepare 25th Amendment paperwork, but Reagan emerged from surgery with doctors predicting a full recovery. During his recuperation, Reagan chose not to step aside temporarily. Given that no one invoked the amendment the day of the shooting, Fielding explained, Reagan had no reason to step aside “by the mere virtue of his understandably reduced schedule. The world had been told he was recovering, and, thankfully, that’s what turned out to be the case.” Not everyone agreed. “There is a substantial difference between the president being able to wave to the crowd from a hospital window and his being able to govern,” said former Attorney General Herbert Brownell, Jr., voicing a sentiment echoed later by Reagan’s White House physician. “If ever there was a time to use it [the amendment], that was it,” Dr. Daniel Ruge said in 1989. “This was not a cold or diarrhea.”

The disability issue arose oddly in 1987, when Howard Baker became Reagan’s chief of staff. Baker and subordinates were warned that Reagan, 76, appeared listless, confused, forgetful, and uninterested in affairs of state. Baker aide James Cannon prepared a memo on involuntary removal. On March 2, 1987, Baker and staff met with Reagan, finding him gregarious, witty, and fully engaged, and quashing talk of removal. But in 1994, doctors diagnosed Reagan with Alzheimer’s disease. Ron Reagan believes his father may have been experiencing early stages of the disease while in office.

The 25th Amendment testifies to American governmental continuity, functioning so effectively that many Americans do not even know it exists. However, an unwanted acid test awaits: a disabled president unwilling to face facts. ✯

To subscribe to American History Magazine, click here.