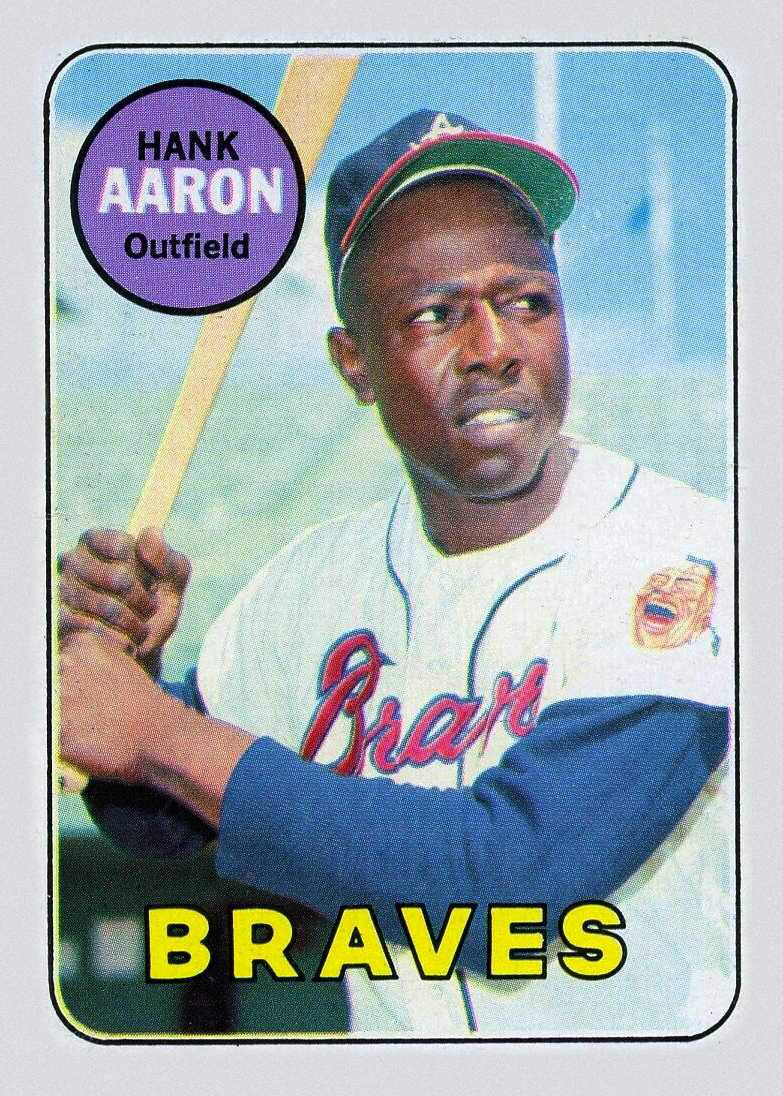

For a brief moment on the evening of April 8, 1974, Atlanta Braves slugger Henry Aaron watched with wonder as the baseball he had just driven toward the brooding, Atlanta sky disappeared over Fulton County Stadium’s left-field wall. The proud, stoic outfielder did not normally admire his home runs, but this one was unique: this was home run number 715—the historic shot that broke Babe Ruth’s much-revered home-run record that had stood for 39 years. When Aaron, bearing an uncharacteristic grin of satisfaction, touched home plate moments later after rounding the bases, nearly 54,000 Braves fans erupted in frenzied delight.

Not every baseball fan reveled in Aaron’s milestone, however. Many white fans were affronted by the notion that a black man could eclipse the record held by their beloved, immortal Ruth. In fact, the smile that blanketed Aaron’s face as he concluded his landmark home-run trot was born as much from relief as from satisfaction. The previous year, as he crept ever closer to the record, had been a private purgatory for Aaron. During that trying 1973 season, he received thousands of mean-spirited letters, some of them vicious and laced with death threats. Guards had to escort him from stadiums; he had even feared for his children’s safety. But through it all, Aaron had kept his emotions to himself, letting his bat do his talking; it was a policy he had followed throughout his career.

Born in Mobile, Alabama, on February 5, 1934, Aaron honed his skills on the area’s rough fields and baseball diamonds. By the age of 17, his hitting prowess had earned him a spot with the famed Negro Leagues’ Indianapolis Clowns, as well as the attention of numerous professional scouts. In 1953, Aaron won the Most Valuable Player award while helping to integrate the Class A South Atlantic League, and the following spring, he reached the majors with the then-Milwaukee Braves.

Seven seasons had passed since Jackie Robinson had broken baseball’s color line, and Henry was among the second wave of black ballplayers who played their way onto major-league rosters. Significantly, the civil rights movement began in earnest that same year, inspired by the Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas Supreme Court case, which overturned the legality of’separate but equal standards across the country.

Baseball may have become society’s vanguard in the war against racial segregation, but as Aaron experienced, many doors still remained, both literally and figuratively, closed to black ballplayers. Robinson had proven that success on the base paths helped to silence the abusers and to quash prejudice on and off the field, and Aaron wasted no time making his mark. In 1957, Hank, as he had been dubbed by the Braves’ publicity director, Donald Davidson, during his rookie campaign, was named the National League’s Most Valuable Player. He was on his way to arguably the greatest career of any baseball player. Over the course of 23 seasons, he would set astonishing new records—for home runs, 755; runs batted in (RBI), 2,297; total bases, 6,856—and add two batting titles, four RBI crowns, and 24 all-star-game performances to his unparalleled résumé.

Today, 15 years after being elected to baseball’s Hall of Fame, Henry Aaron is the Atlanta Braves’ senior vice president and assistant to the president (Stan Kasten), and often represents the organization in community relations activities. In the following interview, Aaron discusses the impact Jackie Robinson had on his career, and also recounts some of the trials he and other black ballplayers faced in crossing the color line.

AMERICAN HISTORY: As a young black ballplayer, what was your reaction when you learned of Jackie Robinson signing with the Dodgers?

HENRY AARON: Well, I guess it was kind of like putting it in the same perspective as the signing of the bill that ended discrimination as far as drinking fountains and railroads and bath facilities, and things like that. Kind of taking a burden off your back, when you felt like Jackie Robinson had done something to give every black kid a chance to live his dream.

AH: Do you recall the time, as a young player, when you first met Jackie?

AARON: When I was in high school—when I was in Mobile, Alabama—I remember Jackie Robinson. They had a farm team in Mobile, and teams always used to come through there to play the Mobile Bears. And Jackie came there to make a speech, and I remember that I stayed out of school to listen to him speak.

AH: Did that speech, and meeting him at that time, set your career on its course?

AARON: Well, he certainly did affect me when I listened to him. But even before then he affected me, just knowing that Jackie Robinson was the first black man that ever played professional baseball certainly inspired me to go ahead and fulfill my dream.

AH: When he came up to the big leagues, did every black baseball fan in America become a Dodger fan?

AARON: I would have to say almost ninety percent of the blacks—of minorities in this country—became Dodger fans. In fact, a lot of them still hold the Dodgers to be true. They still feel like they were the ones who broke the ice, and they need to be loyal to them. You have to remember that black folks are very loyal, and I would have to say that was a turning point in the Dodgers’ career.

AH: There was some comment at the time that Jackie was brought up by Branch Rickey more because of his personality, his upbringing, and his intelligence than for his baseball ability. Perhaps there were more athletic players who could have been brought up?

AARON: I’m sure some of that was true. I’m sure they probably could’ve brought in a lot more, many more, players that had more talent than Jackie Robinson. But that wasn’t the only criteria at that time. You had to have somebody who could deal with the pressure; you had to have somebody who had the outlook of a Dr. Martin Luther King, who could turn the other cheek at times, and also be able to play baseball so that people would appreciate it. So, I’m sure the things mentioned, all of that was true.

AH: What was it about Jackie’s personality that made him a good choice to be the first black man in major league baseball?

AARON: Jackie Robinson was an educated man; he understood the pressure. He understood that if he failed, he would set integration back—as far as baseball—20 or 30 years. He [Rickey] felt like Jackie was intelligent enough to know that he had to—it’s unfortunate—but he had to prove himself, not only to his teammates but to everybody in the country; that if given the opportunity, blacks could play baseball as well as everybody else. But also, that if given the opportunity he could withstand a little bit more than that, because you had a lot of Southerners still playing in the major leagues, and they didn’t like integration. A lot of players on the opposite teams didn’t like it. You also had some teammates that didn’t like him playing in the big leagues.

AH: At the beginning of his rookie year, three of his teammates circulated a petition to prevent him from playing, correct?

AARON: That’s true. So, I don’t know that I could have played under those conditions. I played under a lot of tough conditions, but playing under those conditions where you had some of your teammates, had some of the players . . . you just wondered sometimes if when you walked in the shower, everybody wouldn’t run out.

AH: Over his career, Jackie began to change and became more embittered, did he not?

AARON: He had proven himself, that if given the opportunity he could play baseball. He had proven that to himself, but he was a man, and he had a temper just like everyone else. He felt like he had done all of these things, and he just needed to be his own man. He had a lot of pressure stored up in him from when people would slide into him, slap him, call him names, and all that other stuff. He just felt like he didn’t need to take that anymore.

AH: There was a lot of prejudice in baseball at that time; was it across the board?

AARON: There was a lot of prejudice; I don’t know if it was across the board, but there was enough of it. There was a lot of it there with just about every team in the major leagues.

AH: Was Rickey right to be so careful about the type of player he brought up?

AARON: I thought he brought up the right person. Not everybody, as I’ve said before, could have handled it. Jackie Robinson did handle it. I think the Dodgers was the right club to be with. I think that Jackie Robinson was the right person to achieve this goal.

AH: Was Branch Rickey the right person to embark on this journey?

AARON: Oh yes, no question about it.

AH: Why do you say that?

AARON: He knew what it was going to take, and he foresaw at the time that if Jackie Robinson broke into the major leagues, it was going to change the whole concept of baseball—not only with the Dodgers, but with the whole major leagues. And it did. I think that black players changed the way that baseball was played as far as speed and power and doing some other things. And that holds true right now. When Jackie was playing, and after Jackie and in my era, it has continued that black players, most of them, can do things on the base paths that the average person just can’t do.

AH: Do you think Jackie was aware that this was more than just a sports issue, and was a societal issue as well?

AARON: I think he realized this was more than a sports issue. He had to look at it from the standpoint that he was the prime example. If he failed, baseball was going to be set back 20 or 30 years. And he had the world, everything on his shoulders, as far as baseball and for that matter, sports.

AH: Where would baseball be today without Jackie Robinson?

AARON: You would see guys hitting, going base to base. Ty Cobb, when he played, from what I gather, was one of the greatest players who ever played. Along came Lou Brock, then Rickey Henderson, who erased all those records, and showed that stealing the number of bases that Ty Cobb stole was easy to erase. Along came myself, and I hit 755 home runs. Black baseball players have set all kinds of examples in sports, especially in baseball.

AH: Weren’t there a lot of people rooting against you when it came to setting the home-run record?

AARON: That’s true. That didn’t bother me as much as you hear. Jackie Robinson had set the tone, and I was not about to fold the tent. I was there to perform my duty, and I knew that I had been given the opportunity to play. And just for a few people to write a few letters and all these other things, it didn’t make any difference to me.

AH: When you were a rookie in 1954, how had Jackie broken down some of the barriers? What were some of the challenges you faced?

AARON: I think playing with your teammates was a little bit easier. When Jackie came up, I think his teammates were against his playing in the big leagues. I think when I got to the big leagues, it was a little easier for me to play with my teammates, although I still had problems. Hotels had been integrated in some areas. We still had problems with spring training because most teams trained in the South. But a lot of things had happened before Jackie got there, and after he got there, it was a little easier for black players to get around.

AH: What were some of the changes you noticed?

AARON: When Jackie broke in you couldn’t stay at the same hotel [with the rest of the team]; your teammates, even the teammates you thought were all right, were against you. So all of these things are a lot easier.

AH: The Civil Rights Movement went hand in hand with the start of your career. How did that help baseball?

AARON: I think it all went hand in hand, civil rights and baseball, anything that had to do with breaking down barriers of segregation. Of course, that was the bigger issue—the civil rights issue. As far as hotel accommodations, train accommodations, travel, things like this, it affected a multitude of people, rather than changing for just a few.

AH: How much did the success of black athletes on the playing field help the Civil Rights Movement?

AARON: All of it helped. This country was infested with segregation on all fronts, no matter what it was—baseball, all walks of life. You couldn’t go somewhere to take a drink of water from a fountain. All these areas were affected. So we needed a hand in everything, and baseball did a tremendous job of breaking down some of those barriers.

AH: You’ve sometimes alluded to how difficult the 1973 season was for you.

AARON: The only thing I can say is that I had a rough time with it. I don’t talk about it much. It still hurts a little bit inside, because I think it has chipped away at a part of my life that I will never have again. I didn’t enjoy myself. It was hard for me to enjoy something that I think I worked very hard for. God had given me the ability to play baseball, and people in this country kind of chipped away at me. So, it was tough. And all of those things happened simply because I was a black person.

AH: Would Jackie Robinson have made a good manager?

AARON: I don’t know. I think Jackie would have expected the same out of his players that he himself gave when he played, and that’s kind of hard. Jackie was a perfectionist; he expected players to play as hard as they could no matter whether they were one run in front or twenty runs behind. And players just don’t do it. But I do believe that if Jackie wanted to be a fine manager, he could have adapted and could have been as fine a manager as anyone else.

AH: How far do we have left to go as far as race relations in sports?

AARON: There’s still some problems in this country, and still some problems in baseball. It may not be on the baseball field, but you still have problems in the front office. People shouldn’t fool themselves into thinking baseball has reached the point where all of these problems are eliminated. That is not the case. We still have problems with the front office. They still need to be liberalized a little bit more than they are now.

AH: Are you involved with trying to spur that on?

AARON: There’s no such thing as being involved in it. It’s just that you speak out on it every time it comes forth. You just let people know that baseball isn’t all that we think it is—the American dream.