Present-day White Plains offers few reminders of the American Revolution. In this Westchester County suburb skyscrapers rise amid a bustling downtown surrounded by residential neighborhoods. Thousands live and work in the city, most unaware they do so on what was once a bitterly contested battlefield.

The Battle of White Plains was part of the greater struggle for New York in 1776. After landing on Staten Island that July, a British army under Gen. William Howe drove American troops under Gen. George Washington out of New York City—then confined to the southern tip of Manhattan Island—and environs. By October Washington still held northern Manhattan and the Bronx. Howe planned to isolate him by landing men to the east on Long Island Sound and then driving north and west through Westchester County to the Hudson River, thus cutting the Continental Army lines of supply and communication.

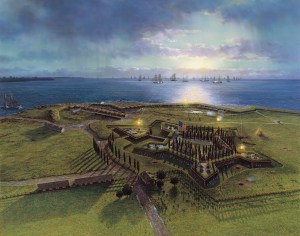

Howe commenced his campaign on October 12 with an abortive attack on the narrow spit of Throggs Neck in the Bronx, followed up six days later by a successful landing at Pell’s Point (present-day Pelham Bay Park). Recognizing the threat, Washington marched the bulk of his army north to White Plains, which stood in Howe’s path to the Hudson. There he constructed entrenchments along the high ground north of town, from Merritt Hill west to the Bronx River. He also stationed troops atop Chatterton Hill, which commanded the west bank of the river.

Howe’s plan was sound but poorly executed. Skirting the coast, the British commander took New Rochelle and sent advance troops to Mamaroneck (the latter just 7 miles east of White Plains), but then dithered as Washington’s vulnerable army redeployed. On October 25 Howe marched his men west to Scarsdale on the Bronx River, but not until the morning of the 28th did he advance north on White Plains.

The heaviest fighting that day centered on the position atop Chatterton Hill. Hessian mercenaries initially forded the river and charged upslope, but the Americans drove them back. A second attack proved more powerful. Hessian artillery set the hilltop ablaze, prompting militia troops to run. Continental regulars stubbornly held on until the Hessians turned their right flank, forcing them to flee.

Howe had taken the high ground, but at a heavy price in blood. Likely with that in mind, he waited for reinforcements before attacking the main Continental lines. Washington took advantage of the lull to withdraw his troops to a line of hilltop entrenchments farther north.

Howe’s reinforcements arrived on the 30th, but then nature intervened, as a cold, heavy rain soaked both armies. When Howe advanced on November 1, he found only abandoned trenches. Washington had slipped still farther north to a fortified position overlooking the village of North Castle, which his soaked, freezing men dubbed “Mount Misery.” Howe sent harassing troops to lure the Americans from their hilltop vantage. When Washington didn’t bite, Howe turned back south to tighten his grip on New York City, having missed a golden opportunity to crush the rebels at a critical moment in the war.

In the ensuing decades White Plains grew by leaps and bounds, swallowing up the battlefield. Chatterton Hill (present-day Battle Hill) is dotted with homes. A park at the corner of Battle Avenue and Whitney Street presents interpretive markers and a pavilion with a battle map—though the view is obstructed—and a small monument stands at the base of the hill on Battle Avenue. The Jacob Purdy House served briefly as Washington’s headquarters. It originally stood near the junction of Water and Barker Streets, but when urban renewal threatened, the White Plains Historical Society [whiteplainshistory.org] moved it in 1973 to its present site, at 60 Park Ave., and deeded it to the city. A small monument on North Broadway marks the center of Washington’s original line, while another sliver of the battlefield remains intact on Merritt Hill, along the 200 block of Lake Street in the village of Harrison. Mount Misery, off nearby Nethermont Avenue in North Castle/North White Plains, remains largely undeveloped, and restored earthworks from Washington’s second line survive in a park off nearby Dunlap Way. The Elijah Miller House, at 140 Virginia Road, Washington’s second headquarters, opened as a museum in 1918 but fell into disrepair. The county initially balked at funding its restoration until nonprofit groups recently stepped up to cover the museum’s operating costs.

That marked the latest chapter in White Plains’ cautionary tale about historic preservation. In 1926 the federal government designated the White Plains National Battlefield Site, but the National Park Service never built facilities or set aside land, instead allowing houses to sprout up at key sites. The fight to preserve the battlefield continues.