Nearly 25 years after it first saw combat in Vietnam, the LTV A-7E Corsair II was headed for retirement when it was recalled for duty in one last war.

During Operation Desert Storm, launched early in the morning of January 17, 1991, the United States deployed a variety of cutting-edge military aircraft as main actors in the air stage, including the Lockheed F-117 Nighthawk stealth fighter. Among the lesser lights in the arena, however, was a small attack aircraft that had left the scene shortly before the beginning of the Gulf War’s initial phase but then had to be hastily returned to service for a curtain call: the Ling-Temco-Vought A-7E Corsair II.

When Iraq invaded Kuwait on August 2, 1990, two of the last operational U.S. Navy A-7E squadrons—the VA-46 “Clansmen” and VA-72 “Blue Hawks”—had just returned from a tour aboard the aircraft carrier USS John F. Kennedy and were transitioning to the more advanced McDonnell Douglas F/A-18C Hornet. But on August 3, both squadrons received an inquiry about a possible new deployment to take part in Operation Desert Shield, the regional reinforcement and preparation for a potential military conflict with Iraq. The Corsair II’s retirement would have to wait.

“There was no deploy order at that point, but we went into overdrive to be ready to answer the call as soon as it occurred,” said now-Admiral Mark Fitzgerald, the last commanding officer of VA-46. The official order came on August 6, with a departure date of the 10th.

At that time the U.S. had two carriers in the Gulf region: Independence and Midway. Independence was well past its scheduled return to America, so it was decided that John F. Kennedy would replace it on station. Six U.S. carriers would eventually serve in the region during the conflict.

When they arrived in the Red Sea, the air wing’s pilots honed their skills during practice missions. “The training flights were amazing,” recalled Fitzgerald. “We flew in northern Saudi Arabia’s famous ‘Star Wars’ canyons on great low-levels.”

Throughout October, with Iraqi president Saddam Hussein showing no signs of retreat, the coalition increased its presence in the region. As the diplomatic situation worsened in December, war seemed inevitable.

The A-7E’s main mission at the start of the campaign would be suppression of enemy air defenses (SEAD). The Corsair II pilots were charged with destroying command-and-control bunkers, air bases, radar systems and anti-aircraft missiles, and they knew how to do it.

On January 14, 1991, VA-46 and VA-72 were told to prepare for action. Saddam had been issued an ultimatum that he had failed to respect, so Iraq’s military forces would feel the full strength of the coalition’s might.

“I was the leader of the Navy flight heading north from the Red Sea and the first aircraft to be launched off the catapult at 0:30 a.m.,” said Fitzgerald. “We went through refueling with USAF tankers and after that we followed to Baghdad. All the anxiety and the adrenaline of the previous days left me on takeoff. All the training and discipline learned from day one of flight school was finally at work.”

The green light for the assault on the Iraqi capital came after initial attacks with F-117s and Tomahawk missiles, which filled the skies with Iraqi anti-aircraft artillery. The A-7 Corsairs were among 84 American and British aircraft that led the initial attacks on Saddam’s infrastructure.

The A-7 mission on that first night would last about five hours. From the Red Sea the Corsairs crossed some 750 miles of Saudi Arabian desert to Arar, on the Saudi–Iraqi border. From there, VA-46 headed on to Baghdad and VA-72 undertook its SEAD mission over H-2 and H-3 airfields in western Iraq.

Clouds covered the route to Baghdad, but as the Clansmen approached the capital the weather cleared and the attack was totally visual. “Near Baghdad, about 70 miles, the weather got clean and the sight was impressive and surreal,” remembered Fitzgerald. “There was literally a dome of lead over the city with missiles crossing the top. The TALD [tactical air-launched decoys], the bombs and Tomahawk missiles had brought every SAM system alive.”

It was the job of a VA-46 junior officer on his first combat mission to serve as radar “bait.” Lieutenant Jeffrey “Spock” Greer, who headed the flight of nine Clansmen A-7Es, would release the decoys that exposed the Iraqi air defenses to the AGM-88 HARMs (high-speed anti-radiation missiles) carried by the other Corsairs.

Greer flew the A-7E “Tartan 310,” with his name written below the cockpit, and carried four ADM-141A TALDs. “The theory was my four TALD would make me look like a flight of five,” explained Greer. “Seeing me coming, the Iraqis would light me up with their radar and start shooting, allowing those behind me to launch HARM missiles up and over me to take out their radars and give the main strike package a clearer route to Baghdad.

“I was the third plane launched off the Kennedy. Planes from all three carriers in the Red Sea rendezvoused on the three KC-135 tankers. Having roughly 36 planes coming from different directions and trying to rendezvous on the three tankers at night was just the first step. After I got my fuel, I proceeded alone on my planned mission route. To make it more difficult to be seen at night, we turned off all of our exterior lights and went in alone. Why alone at night? You can’t fly formation off of a plane you can’t see.

“Each time we rehearsed our night-one mission, we went right up to the Iraqi border and turned around,” said Greer. “On night one, we continued.” This was the main strategy used by the coalition to carry out the first attacks on Baghdad and other locations in the early hours of January 17. Several dozen aircraft took off daily from various locations and simulated the route they would take without actually entering Iraq. For the Iraqis, the 17th was like any other day except that the aircraft kept coming.

After Greer launched the decoys, the following Corsairs fired their anti-radar missiles. “Each HARM-equipped aircraft would fire two missiles from predefined launch positions and the third HARM could be used on targets of opportunity [TOO]—that meant any emitting sites that were still active,” said Fitzgerald. “The prebriefed shots could be fired outside missile range, but TOO range should be much closer. I fired my first missile. I remember that we were warned not to look as the missiles were being released due to the strong bright light of its engine. Of course I looked and had twinkling eyes for a while. On the next missile I didn’t look until it had climbed to its perch at 80,000 feet.”

With two HARMs fired, the missile alert systems in Fitzgerald’s A-7E, “Tartan 312,” came on and blinked. “My scope started showing a symbol totally new for me: a flashing 6 inside a blinking box,” he said. “I studied it a bit too long only to look up and see an SA-6 missile heading in my direction. I quickly shot my last HARM and hit my chaff button. I also made a very hard break turn to get out of its path. In seconds I saw an explosion of the HARM and the SAM warning disappeared, indicating that the missile had done its job.”

Lieutenant Commander Willard R. “Budman” Warfield of the VA-72 Blue Hawks did not participate in the night attacks early on the 17th, but recounted how he waited for his squadron mates to return: “We were told on January 15 that the three-day plan we had been practicing was a go, so there was plenty of time to get the adrenaline flowing. I didn’t get much sleep on the night of the 17th. I attended the night-one briefing, then tried to get some rest prior to the early day-one launch. It was quite a relief to see all our jets come back from night one, but there was no time to spare getting the aircraft turned around for day one. Our ordnance troops did a fantastic job reconfiguring the jets for day-one load out.”

According to Jeff Greer, they expected much more resistance the first night. “It wasn’t too long before we didn’t even see them,” he recalled. “And when we bombed targets, they didn’t know we were there until the first bomb went off. When it did, they started shooting back.” This was standard procedure for Iraqi triple-A and would be seen throughout the campaign.

Six additional VA-46 Corsairs took off shortly before noon on January 17. Four of them each carried three AGM-88 HARMs, destined for further destruction of radars, as well as AIM-9L Sidewinder missiles. Two other A-7Es were armed with AGM-62 Walleye I glider bombs.

The Blue Hawks continued to target the H-2 and H-3 air bases in western Iraq on day one. The daytime actions were a joint effort by aircraft from John F. Kennedy and Saratoga aimed at destroying the operational capabilities of the two bases.

After day one, since Iraqi radars no longer posed a threat to coalition flights, the Corsairs of both squadrons gradually started attack missions using Mk-82, -83 and -84 conventional bombs and Mk-20 Rockeye cluster bombs, as well as the video-guided Walleye I/II bombs and SUU-25 flare launchers (illuminators). Some sorties also featured one or more AN/AWW-9 datalink pods, which were useful for transmitting video camera images from the Walleyes.

Although Desert Storm was the A-7’s last combat operation, it scored a “first” during the campaign. The third night saw the unprecedented use of the AGM-84E SLAM (standoff land attack missile) against high-value strategic targets. On that night VA-46’s A-7s fired two SLAMs at Al-Qa’im, where there were important uranium extraction and refining complexes.

Among the biggest challenges the Corsair pilots faced was inflight refueling. “The KC-135’s refueling process was always a challenge,” noted Fitzgerald. “We had to tank four to five times during a mission and the drogue was just an iron basket with no takeup reel. We got used to and good at doing that on them, but it was always an exciting exercise.”

While the two Corsair squadrons experienced no losses on the first night of attacks, the air battle was not a strictly one-sided affair. During the flight to Baghdad, the fighters, bombers and electronic interference aircraft received information that MiG-25 Foxbats were taking off from Al-Taqaddum Air Base west of the capital. No AWACS (airborne warning and control system) aircraft flying over the region had radar contact with the enemy MiGs thus far, so the F/A-18C Hornets already chasing the threat to the west were not allowed to fire.

After the denial to engage, the Hornets returned eastward and the leader fired his HARM as planned. The second F/A-18C, piloted by Lieutenant Scott “Spike” Speicher of the VFA-81 “Sunliners,” was just behind and would be the next to shoot at Iraqi radar. But before he could loose his missile, one of the MiG-25s also turned eastward and fired a Vympel R-40 missile that swallowed Speicher’s Hornet in an explosion. “The fireball was visible to the north thru the haze,” recalled Fitzgerald. “Hornets were 5,000 feet higher than us so I could see looking up.” Speicher was the first American casualty of the conflict.

Over the ensuing days the campaign followed a rhythm of alternating between SEAD and attack missions. The A-7s participated in a number of important operations, such as the day-three attack on the Al Musayyib rocket test unit, south of the Iraqi capital, using Walleye bombs.

On February 26, two days before the end of the war, a routine mission to H-2 airfield nearly resulted in major losses for VA-72. Bud Warfield recounted the details of that night:

“The original mission was to go to the KTO [Kuwait Theater of Operations] and support advancing coalition troops. They were doing fine without massive airpower, so we were sent to a new target out at H-2—a place we had been before and thought was completely destroyed. [VA-72 executive officer John] ‘Lites’ [Leenhouts] was the strike leader, but his mission was to drop the LUU-2 illumination flares before roll-in. Another officer in VA-72 was to lead the strike element. I was assigned to the spare aircraft on deck. After the strike group launched, I was on my way back to the ready room when I heard “Launch the spare!” over the fight deck loudspeaker. One of the mission aircraft had a hydraulic failure.

“I hauled back to my jet, armed with seven Mk-20 Rockeyes, and did a quick align and launched. I found the rest of the group at the tanker track and refueled. During this time, I found out that the bomber lead had problems with his radios and INS [inertial navigation system]. I was the only ‘adult supervision’ airborne, so he gave me the lead and stayed on my wing the rest of the flight.

“We got up to the target, which we thought was a derelict airfield with no defenses. I rolled in with original strike lead on my wing and searched for a target. We were the first aircraft to attack. I saw some airplanes behind the hangar that had appeared in satellite imagery, and tossed our Rockeyes at them.

“By this time in the conflict, we had noticed that the gunners didn’t start shooting until after first bomb impact. That was true that night. As soon as my bombs impacted, they put up the best AAA show I had seen since then. Flak bursts were going off all around. I started jinking and wanted to get out of there real bad, but was thinking of the 10 guys behind us. I heard Lieutenant [Dan] Wise tell his group to target the muzzle flashes and they did some impressive work. I hit 600 knots at the bottom of the dive run, and pulled up to egress the area at speed. About that time I got a missile warning. I checked our six, and yes, there were missiles in the air. Quite the impressive fireworks show going on over my left shoulder! I expended all the contents of my chaff and flare buckets, while executing 7G break turns in both directions.

“We cleared the area and all aircraft were told to find a wingman of opportunity as all formation integrity was lost. We met up on the tanker, and Lites did a roll call. Somehow, we had all escaped from the hellhole intact. I thought it was a miracle of bad gunnery that no one got hit.

“All that fun was followed with a night trap at 3:30 a.m.,” concluded Warfield. “We debriefed and shuffled off to bed, but there was no sleep to be had.”

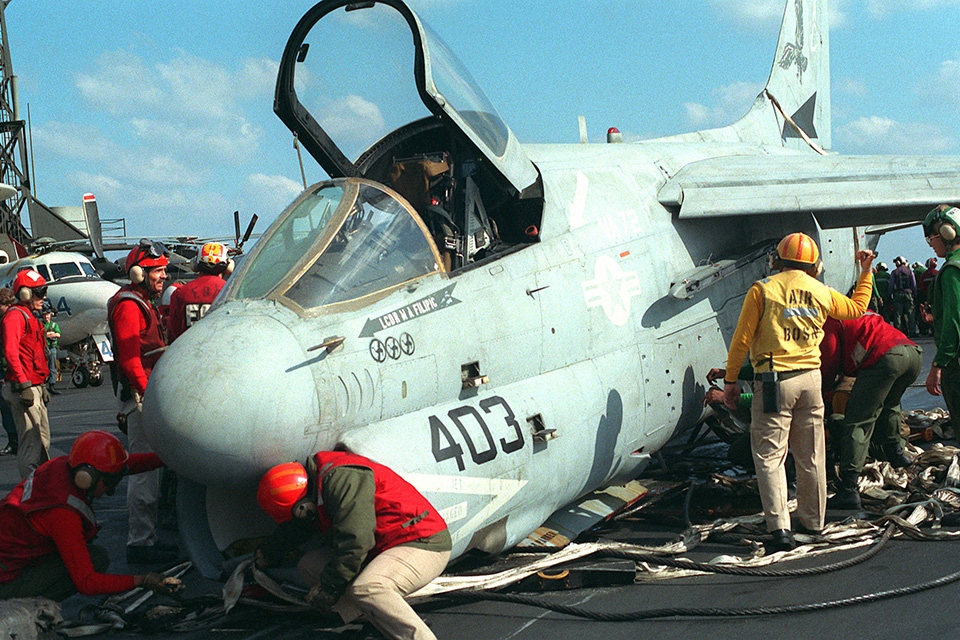

The aging A-7s of the two squadrons maintained an impressive operational capability, with very few aircraft unable to fly when required. An episode involving one VA-72 Corsair, though, deserves a special highlight. A-7E “403” took off for a mission on January 24, damaging its front wheel at the catapult. Unable to complete the mission, the pilot returned to Kennedy and had to land with the aid of the barrier system. All the important equipment was subsequently removed from 403 and the airplane was pushed overboard.

Throughout the Gulf War, not a single A-7 was shot down or even hit by enemy fire, despite expectations of three to five percent casualties. The end of Desert Storm also marked the final act of the A-7E Corsair II’s operational career as a frontline Navy aircraft. On the morning of March 27, 1991, VA-72’s A-7E “412” was the last Corsair to be launched from an aircraft carrier.

The legacy left by the A-7Es during the Gulf campaign is undeniable. According to the 1993 Gulf War Air Power Survey, they dropped approximately 1,000 tons of bombs in 737 combat missions over Kuwait and Iraq, totaling 3,100 combat hours during the 43 days of conflict.

VA-46 and VA-72 were officially deactivated on June 30, 1991, closing the 25-year legacy of a little aircraft that had played an outsized role in the Gulf War victory.

Marcelo Ribeiro da Silva is a Brazilian journalist, military aviation researcher and aviation artist. Further reading: Desert Warpaint, by Peter R. March, and U.S. Aircraft & Armament of Operation Desert Storm in Detail & Scale, by Bert Kinzey.

This feature originally appeared in the November 2020 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here!