The onetime New England shoemaker ventured to California during the gold rush and went wild—hunting, trapping and befriending such grizzly bears as Ben Franklin, Lady Washington and General Fremont.

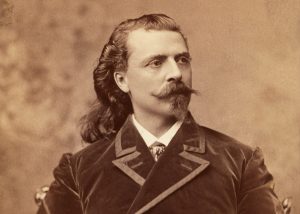

He came from the craggy mountains and brush-choked canyons of the Coast Range, strolling beside a beat-up, creaking wagon. He was in his early 40s, but his white beard and long gray hair made him look much older. His buckskins were torn and dirty; a fur hat covered his head. An assistant named Drury drove the wagon, which was filled with cages holding foxes, wolves and smaller animals. Tethered deer, elk and antelope kept pace with the caravan, and tied to the wagon’s back axle and trotting along on their own tethers were two large bears—grizzlies.

The California mountaineer in charge of this motley mid- 19th-century procession carried a stick he readily wielded on any misbehaving beast. He was constantly training the animals—to respect each other and their master and to obey orders. He also taught them tricks. The two grizzly bears, Benjamin Franklin and Lady Washington, could wrestle, turn somersaults and carry their master bareback.

When the animal parade passed through villages or farmland, people stopped and stared, then would follow for a time, at a safe distance. Some would shout questions at the mountain man, and he would answer them, good-naturedly. When they asked what kind of bears were tied to the axle, he gave them an honest answer, “Grizzly bars!” The gawking crowd would then drop farther back. Each day in California grizzlies were killing hunters, ranchers and livestock; many people considered them no-good natural-born killers. But the bearded, buckskin-clad man regarded them differently. His name was Grizzly Adams, and bears were his business.

In the September 30, 1891, San Jose Evening News, someone, perhaps Adams’ assistant Drury, recalled coming to San Jose with a show four decades earlier. “It was the famous bear show of Grizzly Adams,” he wrote, “and I don’t suppose there is a single old Californian in San Jose or any other town in this state but that remembers old Grizzly and his bears.”

“Old Adams,” as he was known at the time, put on his ragtag show in San Jose and several smaller towns while en route to San Francisco in the summer of 1856. After finding a suitable corral, Adams would set his animal cages around the inside perimeter, then allow the animals to roam freely inside as he guided them through their various acts. It was pretty crude stuff, but the public loved it. And once Old Adams arrived at the great city on the bay, the legend of Grizzly Adams blossomed.

John Capen Adams, the man with this amazing affinity for animals, was born in Medway, Mass., on October 22, 1812. He trained as a shoemaker but preferred to be outdoors, so he tried his hand at catching wild game for a touring animal show. After a tiger mauled him, he returned to cobbling. Adams married on April 12, 1836, and settled down with his wife and three children in Brookfield, Mass. Then, in 1849, he left his family behind and joined the California Gold Rush. By the fall he was squatting on 160 acres near Stockton and had stocked his land with cattle. He also staked several mining claims near Sonora, purchased a store and saloon on Woods Creek and bought into a scheme to dam the Tuolumne River in order to mine the riverbed. The scheme failed when a major rainstorm in the mountains flooded out all the mining and dams below.

More bad luck followed. Adams was informed that his cattle had all been stolen and that someone already had a claim to his land. Other miners sued him in 1851 for not sharing his water with them, and then Adams sued a neighbor for jumping his claim. Though he had to mortgage his properties to pay an attorney, he continued to buy other properties. Adams’ house of cards collapsed when he tried to use already mortgaged land as collateral.

Hauled into court, Adams blew up, denouncing the law in general and lawyers in particular before abruptly departing. He had nothing to show for his hard work in California except a wagon, a pair of oxen, several rifles, a Colt revolver, a few clothes and blankets and some cooking and eating utensils. Still, that was enough for a man who wanted to get away from it all, especially the law. Adams headed into the Sierra Nevada in the summer of 1853, determined to shun society and live with the animals in the forest. “The mountain air was in my nostrils,” he later said, “the evergreens above and the eternal rocks around; and I seemed to be a part of the vast landscape, a kind of demigod in the glorious and magnificent creation.” Although his given name was John, he operated as James Capen Adams and generally signed his name “J.C. Adams.” Soon, he would be better known by various nicknames.

That fall, with the help of several friendly local Indians, Adams built a shelter east of Sonora near the Stanislaus River and learned to live off the land. He also hunted and trapped bears and other animals, selling skins and meat in the settlements, while caging many animals at his primitive camp. He became fascinated with the California grizzlies, which were mightier than the black bears he had seen back East. “Like the regions which he inhabits,” Adams later wrote of the grizzly, “there is a vastness in his strength, which makes him a fit companion for the monster trees and giant rocks of the Sierra and places him, if not the first, at least in the first rank of all quadrupeds.”

John Capen Adams, the man with this amazing affinity for animals, was born in Medway, Mass., on October 22, 1812. He trained as a shoemaker but preferred to be outdoors, so he tried his hand at catching wild game for a touring animal show. After a tiger mauled him, he returned to cobbling. Adams married on April 12, 1836, and settled down with his wife and three children in Brookfield, Mass. Then, in 1849, he left his family behind and joined the California Gold Rush. By the fall he was squatting on 160 acres near Stockton and had stocked his land with cattle. He also staked several mining claims near Sonora, purchased a store and saloon on Woods Creek and bought into a scheme to dam the Tuolumne River in order to mine the riverbed. The scheme failed when a major rainstorm in the mountains flooded out all the mining and dams below.

More bad luck followed. Adams was informed that his cattle had all been stolen and that someone already had a claim to his land. Other miners sued him in 1851 for not sharing his water with them, and then Adams sued a neighbor for jumping his claim. Though he had to mortgage his properties to pay an attorney, he continued to buy other properties. Adams’ house of cards collapsed when he tried to use already mortgaged land as collateral.

Hauled into court, Adams blew up, denouncing the law in general and lawyers in particular before abruptly departing. He had nothing to show for his hard work in California except a wagon, a pair of oxen, several rifles, a Colt revolver, a few clothes and blankets and some cooking and eating utensils. Still, that was enough for a man who wanted to get away from it all, especially the law. Adams headed into the Sierra Nevada in the summer of 1853, determined to shun society and live with the animals in the forest. “The mountain air was in my nostrils,” he later said, “the evergreens above and the eternal rocks around; and I seemed to be a part of the vast landscape, a kind of demigod in the glorious and magnificent creation.” Although his given name was John, he operated as James Capen Adams and generally signed his name “J.C. Adams.” Soon, he would be better known by various nicknames.

That fall, with the help of several friendly local Indians, Adams built a shelter east of Sonora near the Stanislaus River and learned to live off the land. He also hunted and trapped bears and other animals, selling skins and meat in the settlements, while caging many animals at his primitive camp. He became fascinated with the California grizzlies, which were mightier than the black bears he had seen back East. “Like the regions which he inhabits,” Adams later wrote of the grizzly, “there is a vastness in his strength, which makes him a fit companion for the monster trees and giant rocks of the Sierra and places him, if not the first, at least in the first rank of all quadrupeds.”

A Sonora merchant named Solon hired Adams as a hunting guide to the recently explored Yosemite Valley. It was early November 1853, and although a few hardy souls had ventured into this mountain sanctuary (see “Westering Walker,” by Kate Ruland-Thorne, in the August 2009 Wild West), few had risked the barely discernible Indian trails or had any idea of the breathtaking beauty of that rocky gorge. Adams, in the company of his greyhound hunting dog, Solon and a string of pack animals, was on the rim of the valley in three days.

“The first view of this sublime scenery was so impressive,” the mountain man later recalled, “that we were delayed a long time as if spellbound, looking down from the mountain upon the magnificent landscape far below.”

As they descended into the valley, the two hunters kept busy killing and skinning game. Adams found a likely bear den that he watched for three days. When a great female grizzly emerged one morning, he distinctly heard the sounds of cubs behind her. Wanting cubs to train, he knew what he must do. Carefully working his way closer through the brush, he shot the mother griz in the chest, and she toppled over backward. She was pawing and biting the ground when Adams rushed at her and fired six shots into her from his revolver. “Leaping forwards,” he later wrote, “I plunged my knife into her vitals. Again she endeavored to rise but was so choked with blood that she could not. I drew my knife across her throat.”

As Adams carried her two cubs back to camp, he realized he had a serious problem: Their eyes were closed, which meant they were still on mother’s milk. A mixture of sugar, water and flour proved inadequate for their needs. It happened, though, that his greyhound had just given birth to a litter of pups. Despite some argument from the dog, Adams killed all but one of the pups to make room for the two bear cubs at the greyhound “dinner table.” Adams named his favorite cub Benjamin Franklin, while Solon called the other one General Jackson. After selling bales of hides, bear oil and bear meat at exorbitant prices in nearby settlements, the two men returned with their pets to Adams’ camp above Sonora.

That winter Adams’ brother William reportedly found him in his winter camp, and the two had a happy reunion. According to the story John later told, William had been a successful miner in northern California and was headed home with a heavily laden gold poke. William wanted John to return with him to Massachusetts, but mindful of his comparative lack of success, John chose not to go. William then offered to finance an expedition to Oregon. John was to capture a cargo of bears and other wildlife, then ship them to Boston, where William would sell them to menageries and circuses. The main trouble with this story is that there is no record of Adams having had a brother named William. Who William actually was remains a mystery.

In any case, by the summer of 1854, Adams, with the help of Indian friends, had moved his growing collection of animals to Hooperville, near the mining camp of Mariposa. Adams picked that location as it already had a stout corral that had been used for bear and bull fights. Adams chained his animals around the perimeter of the corral, determined to put on an animal show of his own.

Adams’ plan was to have trained bears wrestle each other, perform tricks and race one another. Next would be a fight between two bears, then one of his larger bears would take on a pack of local dogs. Adams would offer cash prizes for the best performing dogs. Such contests were quite popular at the time, and Adams had high hopes of big crowds. He hired a small band and a bartender for the festivities. “‘Wild Yankee’ is making the ‘most extensive preparations’ for the entertainment of his friends next Sunday at Hooperville,” The Mariposa Chronicle announced on March 10, 1854. Two days later, the show debuted. Adams pitted a young grizzly named Tom Thumb against three bears, and a larger grizzly, Jenny Lind, took on six dogs. The show was a rousing success, as was another one at Hooperville on March 26. The man known as “Wild Yankee” or, simply, the bear tamer followed up with an early April show in Hornitos, west of Mariposa. Then it was off to Oregon to fulfill his contract with his “brother.”

Adams bought supplies and exchanged his oxen for a string of pack mules at the Howard brothers’ ranch below Mariposa. A young hunter named William Sykes and two of Adams’ Indian friends joined him on the expedition to the Northwest. Following old Indian trails, they reached a game-rich valley in eastern Oregon in a few weeks. There, they set up camp, setting out their traps and cages. Adams was particularly interested in obtaining trainable grizzly bears. He found plenty of bear tracks and soon ambushed a female grizzly, firing one shot into her breast and a second shot through her open mouth into her brain. Catching her two confused but ferocious cubs proved more difficult than he expected, but at last he lassoed them and chained them to trees until ready to begin their domestication. Both were more than a year old and would not let him approach. He concentrated on the female cub first.

“I stepped back into a ravine,” recalled Adams, “cut a good, stout cudgel and, approaching with it in my hand, began vigorously warming her jacket. This made her furious… not that she was hurt, but she was so dreadfully aroused. …Finally, she acknowledged herself well corrected and lay down exhausted.…In a short time afterward I patted her shaggy coat; and she gradually assumed a milder aspect.” The seemingly cruel tactic proved a success, and soon the she-cub was his great pal. Carrying a coat of thick, coarse fur and a heavy layer of fat beneath its skin, a grizzly actually feels more pressure than pain in such a beating. Adams called her Lady Washington and came to regard her as special. She would share his “dangers and privations,” he said, and he even taught her to carry packs on her back while they were traveling. The other cub was successfully enrolled in the same school of hard knocks.

When Adams had captured enough animals, he herded and carried them in cages to Portland, then placed them aboard ship for the long trip to Boston. Adams kept the rapidly growing Ben Franklin, Lady Washington and several other animals for his own collection and returned to California. He continued to hunt and trap in Corral Hollow on El Camino Viejo, the old Spanish road, and then roamed the Kern River and Tejon Pass, obtaining meat and adding a variety of wildlife to his entourage. Exactly where he went and when is hard to establish, in no small part due to Adams’ propensity for telling a good story, but he clearly covered much ground on his excursions.

At one point, he related to the San Francisco Bulletin a few years later, he had a dangerous encounter with a mother bear with three cubs. The she-bear knocked his rifle from his hands with her left paw and struck him to the ground with her right. She then bit into his back, tearing away his buckskin coat and flannel shirt. Ben Franklin, Adams’ “tame” grizzly, distracted the she-bear with a bite to her haunch. As grizzly turned on grizzly, Adams climbed a tree. The newspaper report continued: “He saw the savage beast, after biting into Ben’s head and destroying one of his eyes, drop her hold, crush him against the ground, put her foot upon him, take a new hold with her fangs in his shoulder and rising with him in her mouth, shake the poor fellow almost to pieces. It was a terrible sight to see this monster combat.” Finally Adams was able to reload his rifle and shoot the she-bear through the heart. In another encounter, a grizzly struck Adams violently on the head, tearing off his scalp and punching a hole in his skull. There were other close calls, but as Adams returned from his southern jaunt, he could rejoice in his wonderful collection of badgers, wolves, elk, antelope and bears. And the Howard brothers were boarding more animals for him at their ranch.

Following the series of shows in San Jose and Redwood City in the summer of 1856, Adams set up base at 143 Clay Street in San Francisco. He placed his caged animals against the walls of the building’s large basement, while Lady Washington and Ben Franklin wore heavy leather collars fitted to 5-foot chains anchored to bolts in the floor. Outside, Adams nailed up a sign proclaiming his establishment the MOUNTAINEER MUSEUM. A visitor reported “10 bears of various kinds, a California lion and tiger, several eagles, several elks and several Sierra Nevada cats, or martins.” That was before Adams took shipment of the animals from the Howard ranch.

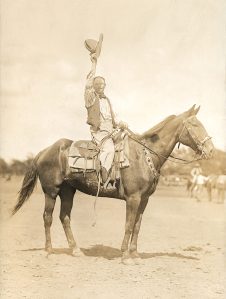

Adams, in his buckskin suit, would lead crowds through the “museum” and demonstrate his control over Lady Washington and Ben by climbing on their backs. The October 21, 1856, Daily Alta California reported: “His celebrated bear, ‘Ben Franklin,’ is a perfect wonder in his way. His keeper mounts and gives him an invitation to shake him off; bruin stands on three legs and rolls like an elephant, but when this method fails, he throws back his paws and claws his rider down. He stands upon his hind legs, and his keeper gives him a gentle shove, and over and over and over he goes as if impelled by an irresistible force.”

When he could afford it, Adams moved to the California Exchange building and renamed his collection the Pacific Museum. Feeding time was particularly entertaining, as reported in the May 4, 1857, Daily Evening Bulletin under the headline GRIZZLY CUBS AT THE PACIFIC MUSEUM: “One of the most amusing sights to be seen, at the present time, in San Francisco, is the feeding of the three grizzly bear cubs at the Pacific Museum. A bowl of corn meal and milk is placed before them, and to see the voracious little savages ‘pitch in’ is wonderful.”

Adams continued to engage in trapping expeditions, lend out his bears for the popular bear and bull fights and take groups of his animals to Sacramento and other California cities for special exhibitions. San Franciscans grew used to seeing Old Adams the bear tamer and Ben Franklin or Lady Washington out for an evening stroll on the boulevard. Adams’ energy, belying his gray hair and shaggy white beard, seemed boundless.

Gentle Ben, referred to in the press as “the ‘star’ animal in Adams’ wonderful collection,” took sick and died in early 1858. Adams reportedly became distraught, and by late 1859 attendance and revenues had fallen off while maintenance costs (animal feed and salaries to pay helpers, the band and clean-up crews) had soared. The Adventures of James Capen Adams, Mountaineer and Grizzly Bear Hunter of California, which Adams dictated to Theodore Hittell, was due to be published in San Francisco, but Adams had already made up his mind to move his museum to the East.

His plan was to transport his menagerie to New York City and then take the show to Europe. On September 30, 1859, the Daily Evening Bulletin published an inventory of sorts: “The collection consists of 10 or 12 specimens of the grizzly bear, one of which is the largest ever caught. There are also specimens of the black and brown and cinnamon bears, besides a large number of the other animals of the West— elk, deer, buffalo, coyote and many birds, including the California condor, various eagles, pelicans and other species of the feathered tribe. There are also a number of sea lions, which will also be taken if possible.”

With his customary zeal, the old hunter packed the hold of the clipper Golden Fleece with barrels of water, dried meat, straw and other types of fodder for his crew of animals. There were 19 crates in all, varying in size, but most 10 feet long, 4 feet wide and 4 feet high. The grizzlies—Samson, Lady Washington and General Fremont—had their own cages, while smaller animals shared quarters. They set sail on January 7, 1860, on a voyage of more than three months.

On January 31, 1860, The Sun ran a story titled AN ASSORTED CARGO: “A ship has sailed from San Francisco for the city of New York with a cargo consisting of hides, horns, old copper, old iron, grizzly bears, old junk, California lions, bales of rags, a sprinkling of cougars, leopards, old rope and Old Adams himself, the famous grizzly bear tamer. Adams is bringing his California menagerie to the Atlantic States for exhibition. Adams had also skipped out on a $1,400 suit against him in San Francisco. There was time enough to worry about such things if and when they caught up with him. Fixing up a temporary quarters for his menagerie in the hold of the ship was all that concerned him.”

Soon after arriving in New York, Adams walked into showman P.T. Barnum’s office in New York’s American Museum. To raise some operating capital, Adams had sold an interest in his animals to a man who, in turn, had sold the paper to Barnum. Barnum announced he was already a partner and was thrilled to be able to add Adams’ menagerie to his museum. “He was dressed in his hunter’s suit of buckskin, trimmed with skins and bordered with the hanging tails of small Rocky Mountain animals; Old Adams was quite as much of a show as his beasts,” Barnum recalled in his 1873 book Struggles and Triumphs, or 40 Years’ Recollections of P.T. Barnum. “They had come around Cape Horn…and a sea voyage of three and a half months had probably not added much to the beauty or neat appearance of the old bear-hunter.” In conjunction with James T. Nixon, Barnum promptly engaged his publicity machine to turn out flyers, ads in the major newspapers and a booklet on Adams’ rousing life. It was Barnum who consistently called his new associate “Grizzly Adams” and made that nickname stick.

Barnum erected a large tent in the big city on 13th Street between Broadway and Fourth Avenue for the initial showing. The May 12, 1860, New York News ran the story of OLD ADAMS AND HIS GRIZZLY BEAR: “This unique dual, or duo, created quite a sensation yesterday in our principal thoroughfares, preceded by an immense nondescript, called a wagon, drawn by eight horses, which bore a band of music. Old Adams, as he delights to be called, followed on an immense stage, having for his companion his special pet, a grizzly bear, which he has subdued to the submission of packsaddle and bridle.…Many a looker-on shuddered at the thought that the unwanted sight and noise might arouse Miss Grizzly, and in a fit of feminine disobedience she might turn upon her lawful master. However, no such accident or incident occurred, and the happy pair were landed safely at their new quarters in 13th Street.”

The city crowds were tremendous, as were the proceeds, but the unpredictability of Adams’ ferocious wards surfaced in mid-May 1860. There was a large, round railing in the center of the tent where various bears performed their stunts as Adams walked among them. During this particular show, as he was coaxing General Fremont to perform, the great bear suddenly turned on him and seized his left arm in his mouth. There were gasps and screams from the crowd as women ran for the exits and Adams struggled with the bear. Adams’ dog, Rambler, finally dashed in and distracted the bear long enough for the hunter to break away. “He is,” noted a newspaper account, “a man of extraordinary nerve and, in spite of the severe injuries from which he is suffering, continues his exhibition.”

The incident may have prompted Barnum to initiate a Connecticut tour for the Adams show, in conjunction with Nixon’s Mammoth Circus. Now Barnum was billing the hunter as “Old Grizzly Adams.” But a looming problem could not be ignored. When Adams and Barnum first met, the old hunter had doffed his fur cap, exposing a terrible head wound, a memento from his scrap with a wild grizzly. The injury was further aggravated when a monkey later jumped on the trapper’s head and bit into the wound. And one of his own bears had since smacked his head. “His skull was literally broken in,” Barnum later wrote. “The last blow, from the bear called General Fremont, had laid open his brain so

that its workings were plainly visible.”

Barnum knew the old trapper was dying and had already hired his replacement. Adams had no illusions about the state of his health. The previous month he had sought the advice of the New York College of Physicians and Surgeons, but they could only tell him what he already knew. “When the heart beats,” the examining doctor reported, “if the head is uncovered, the pulsations can be seen in the boneless portion of his cranium.” The wound refused to heal, and there was no hope.

Nevertheless, the old mountain man would not give up. Keenly aware of the years of estrangement from his family, he was anxious to establish financial security for his wife. He bargained with Barnum to allow him to stay with the show as long as he was able. Happy to placate the old hunter, Barnum offered him $60 a week and expenses but strongly suggested he return home in his final days of life.

“What will you give me extra,” asked the grinning hunter, “if I can stay with the show for 10 weeks?” Barnum was astounded but offered an additional $500 if he managed to finish out the term. After signing a contract to pay the stipulated amount to his wife, Adams had her join him for this final tour. Barnum met the couple at several stops and found Adams growing progressively weaker.

In mid-June another disturbing incident occurred. The Connecticut Constitution of June 20, 1860, reported: “Adams was exhibiting his bears as usual, at his menagerie, when the black hyena bear, so called from his excessively bad temper, made a dart at him and seized him by the calf of his leg, biting it right through and raising him from the ground in the act. Shaking him freely, the bear then threw him to a distance of five or six feet. Luckily for the old trapper, his dogs rushed in at the infuriated animal, or he would have…repeated the attack. A fierce combat ensued, and the bear nearly killed the largest of the dogs, but by this time Old Adams was again on his feet, assisting his trusty canine friends.” It was another close call, but the old trapper kept going, chiding Barnum all the time that he was going to lose his $500. “I met him the ninth-week in Boston,” Barnum recalled. “He continued to exhibit the bears, although he was too weak to lead them in.” Staying with Adams for the 10th week, Barnum gladly paid the bear man his $500. “He took it,” continued Barnum, “with a leer of satisfaction and remarked that he was sorry I was a teetotaler, for he would like to stand treat!”

And so Grizzly Adams went home. Though he was only 48 years old, it was a scarred, tired and sick old man who finally returned to his wife and daughter at Neponset, Mass. Even there he could not remain in bed, and one day he took the horse cars into town. On the return trip, the jolting of the cars opened the wound in his head, and blood burst forth, spattering on the ceiling to the horror of his fellow passengers. The bloody Adams was carried into a nearby drugstore and a physician summoned. He was taken home some time later, and all knew his time was short. At the behest of the family, a minister was present at the end.

When asked about his faith, the old hunter offered an unusual response, as recalled by Barnum: “I have attended preaching every day, Sundays and all, for the last six years. Sometimes an old grizzly gave me the sermon, sometimes it was a panther; often it was the thunder and lightning, or the hurricane on the peaks of the Sierra Nevada.” Grizzly Adams was a showman to his last breath on October 25, 1860.

Hittell’s biography of Adams, published in San Francisco shortly after the hunter sailed for New York, was also published in Boston, much to the delight of Barnum. Publications nationwide reviewed the book, and excerpts of his adventures spread the fame of Grizzly Adams far and wide. After Adams’ death, Barnum reportedly shipped the bear show to Cuba for a tour and then on to England. Grizzly Adams became so well known that actors portrayed him on the stage as late as 1890. His name resurfaced in the 1974 movie The Life and Times of Grizzly Adams, which spawned the short-lived TV show of the same name. Dan Haggerty played the kinder, gentler Grizzly Adams. But there has never been anyone quite like the real Old Adams.

William B. Secrest writes often about people and events on the California frontier. His 2008 book California’s Day of the Grizzly (Quill Driver Books/Word Dancer Press, Sanger, Calif.) is recommended for further reading, along with The Adventures of James Capen Adams, Mountaineer and Grizzly Bear Hunter of California, by Theodore H. Hittell.

Originally published in the February 2010 issue of Wild West. To subscribe, click here.