In the early months of 1863, Major General U.S. Grant’s primary objective was Vicksburg, the last Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River. If that city could be taken, the North would control the entire river, splitting the Confederacy down the middle. Before Grant could take Vicksburg, however, he had to get there, which was proving to be a very annoying problem.

Grant’s three divisions were located well north of their target, on the wrong side of the Mississippi. Traveling directly downriver would require running Rebel batteries at Vicksburg, something Grant was hesitant to try. But all other endeavors to advance southward, including two attempts to dig canals bypassing Vicksburg and two attempts to force passage through the swamps and bayous east of the river, had failed miserably.

Finally, on the night of April 16, ironclads and supply-laden transports steamed past the Vicksburg guns. Confederate cannons blasted away at the steam-driven fleet, but only a single transport was lost. Another successful run was completed on April 22. Grant’s infantry had already marched south, and with supplies and river transports now plentiful, the Union Army could finally cross the watery barrier.

A major part of Grant’s plan was to distract the Confederate commander, Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton, while he crossed the river and swung around to approach Vicksburg from the east. Major General William T Sherman played a part in the plan: his division remained north of Vicksburg, demonstrating against the Chickasaw Bluffs. The local Confederate commander sent a panicky message to Pemberton, claiming that ‘the enemy are in front of me in force such as never before been seen at Vicksburg. Send me reinforcements.’ In reality, Sherman represented only about a third of Grant’s command and probably could not have taken the bluffs if he tried. (In fact, he had already tried and failed the previous December.) Nevertheless, Pemberton sent 3,000 troops that had been marching south to oppose Grant.

Another diversion, one that would prove wildly successful, was a cavalry raid launched into Mississippi from La Grange, Tenn., on April 17. It was the beginning of 16 days of nearly non-stop movement, widespread destruction and frequent battle. When it was over, Grant would accurately describe it as one of the most brilliant cavalry exploits of the war.’

Grant had first considered such a raid as early as February 1863, suggesting a volunteer force of 500 be used. As his strategy evolved, the importance of the raid increased. By mid, March, the strength of the raiders had been dramatically enlarged and the volunteer stipulation had vanished.

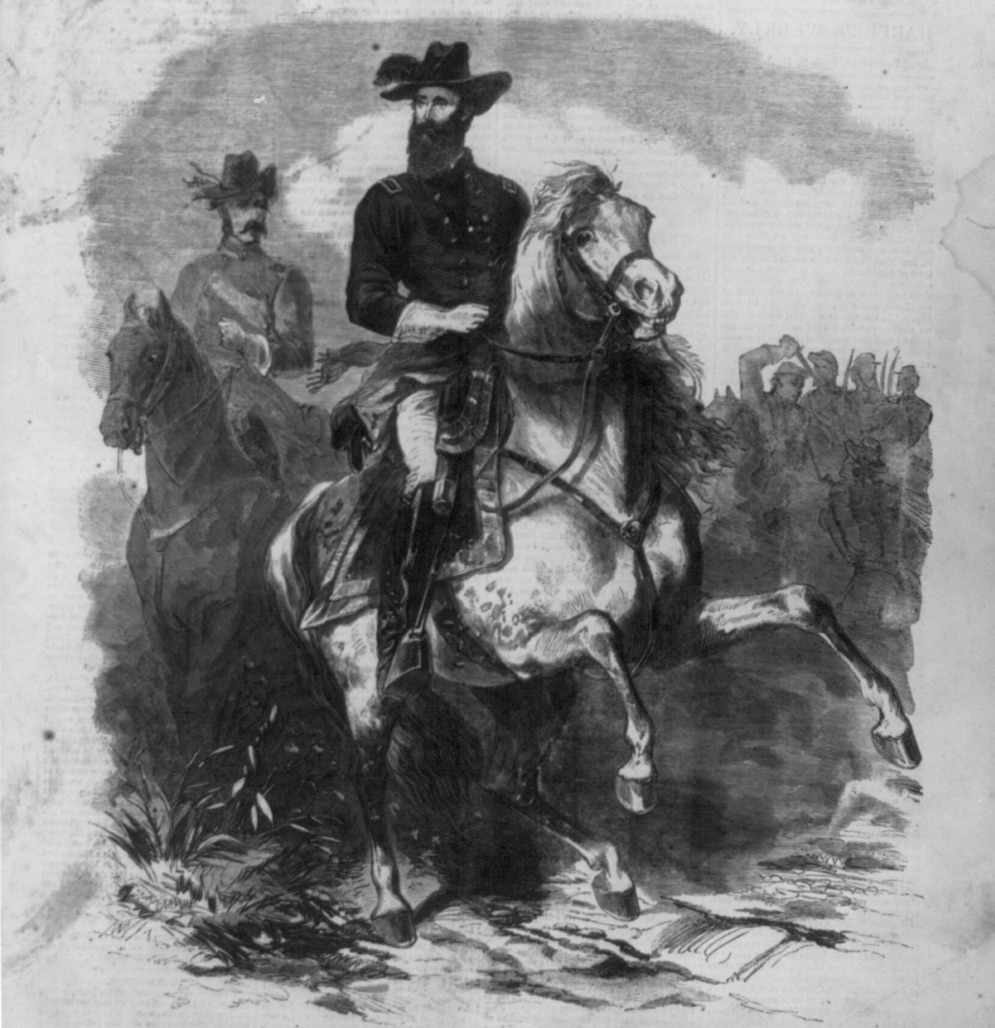

The man assigned to lead the raid was 36-year-old Colonel Benjamin H. Grierson, a prewar music teacher from the Midwest who, in less violent times, had traveled to various small towns organizing amateur bands. Later he went into the produce business and, in 1860, wrote campaign songs for Abraham Lincoln. When the war began, Grierson enlisted as a private in the infantry. He very much wanted to do his share of the fighting on foot; while a child, he had been kicked in the face by a horse and still harbored a severe dislike for the equine creatures.

This was not to be. In May 1862, Grierson was commissioned a major in the 6th Illinois Cavalry. A man with little military training or experience–and a pronounced dislike of horses–would soon prove to be one of the most skilled cavalry leaders of the war.

The raid began at dawn on the 17th. Grierson rode south from La Grange with 1,700 men: Colonel Reuben Loomis’ 6th Illinois Cavalry, Colonel Edward Prince’s 7th Illinois Cavalry, and Colonel Edward Hatch’s 2nd Iowa Cavalry, along with a battery of six 2-pounders. Grierson alone knew the extent of their orders, to penetrate deep into the Rebel-held state, cut Pemberton’s supply line, and then return to Union lines by whatever route seemed best. To guide him, Grierson brought a compass and a pocket map of Mississippi.

They moved quickly, covering 30 miles on the first day. During the afternoon of the 18th, they crossed the Tallahatchee River at three separate points. A battalion of the 7th Illinois was the first to meet opposition. Crossing at New Albany, they encountered Southern troops attempting to destroy the bridge. The Illinoisans advanced and were fired on. They pressed forward, and the outnumbered Rebels were forced to run. The bridge was repaired and the crossing made.

Six miles farther up the Tallahatchee, Hatch’s 2nd Iowa also met the enemy, numbering about 200. Hatch fought skirmishes that day and the next morning. Armed with Colt revolving rifles, Hatch’s men emerged victorious, taking a number of prisoners.

After a night of torrential rains, the command re-formed on April 19 and continued south to Ponotoc, where they burned a mill and again skirmished with Confederate soldiers. Dawn of April 20 found the Northerners 80 miles inside Confederate territory, with Grierson forming his men for inspection. He culled out 175 men suffering from dysentery and saddle galls. Calling themselves the ‘Quinine Brigade, ‘ these men escorted the prisoners back through Ponotoc that night, in the hopes of convincing the Confederates that the entire command was returning to Tennessee. Grierson himself continued south with the two Illinois regiments, while the 2nd Iowa and a 2-pounder broke off and turned eastward the next morning, with orders to cut the Mobile & Ohio Railroad.

Hatch’s men arrived at Palo Alto that afternoon, drawing Confederate cavalry away from Grierson. Hatch was met by Lt. Col. C.R. Barteau’s 2nd Tennessee Cavalry. A skirmish ensued, and the Iowans’ revolving rifles again gave them a decided advantage. Hatch retreated north along the railroad, with Barteau in close pursuit. He destroyed the rails at OkoIona and Tupelo. Barteau caught him again near Birmingham on April 24. After a two-hour battle, Hatch retreated across Camp Creek and burned the bridge behind him. Barteau, his own men exhausted and his ammunition low, gave up the pursuit.

Hatch returned to La Grange on April 26, his diversion within a diversion a roaring success. He brought with him 600 horses and mules, with about 200 able-bodied civilians to lead them, and claimed 100 Confederate casualties while losing only 10 men himself

Grierson, in the meanwhile, had not been idle. Hatch had drawn away what little cavalry the Confederates had to field in northern Mississippi (most had been detached to General Braxton Bragg in Tennessee), and Grierson’s 950 remaining men could gallop south without worries of pursuit from the rear.

They entered Starkville about 4 p.m. on the 21st, capturing and destroying government property. just south of town, Grierson detached another unit to operate independently. The 7th Illinois’ Company B, under Captain Henry Forbes, moved east, then galloped south down the Mobile & Ohio Railroad. They raided Macon, and despite the tiny size of his command, Forbes demanded that the town of Enterprise surrender to him. Not surprisingly, Rebel troops there refused and Forbes moved on to rejoin Grierson at the Pearl River.

By now, the Confederates were desperate to stop the Union raiders. Thanks to Hatch, Forbes, and the Quinine Brigade, Pemberton was receiving confused and exaggerated reports of Grierson’s strength and position. Lacking sufficient cavalry, he was diverting more and more infantry from Vicksburg and Grand Gulf, where Grant was preparing to cross. An infantry brigade marching to Vicksburg from Alabama was halted at Meridian. Three regiments and supporting artillery were sent to Morton against the possibility that Grierson might turn toward Jackson, Pemberton’s headquarters. Routes north and northwest were blocked by troops at Okolona, Canton and Carthage. Troops as far away as Port Hudson, La., were mobilized against the hard-riding former music teacher.

All was to no avail. It was swift-footed cavalry against slow, plodding infantry. It was impossible for the Confederates to effectively close in on Grierson’s men.

Leaving Starkville, Grierson moved south toward Louisville, Miss. His Illinoisans pushed through a swamp–‘a dismal swamp nearly belly-deep in mud,’ as Grierson later described it–and swam their horses across streams. He detached a battalion to destroy a large tannery and shoe factory. The battalion succeeded, doing an estimated $50,000 in damage.

They pressed on, still moving, with no road visible, through the swamp and water of the Nuxubee River bottom, arriving at Louisville after sunset on the 22nd. Grierson threw out two battalions as pickets, bottling up the citizens to prevent any information about his route from getting out. Still, he showed real concern that Southern civilians and their property be protected, as the orders to the pickets included instructions to ‘drive out stragglers, preserve order, and quiet the fears of the people.’ Considering the behavior of many Union soldiers regarding the South during the war, such concerns were not unfounded. Grierson, though, could later write with justifiable pride that ‘they [the Southerners] were protected in their persons and their property.’ His men passed through Louisville without incident.

They soon struck another swamp and lost several horses to drowning. By midnight, they had reached a plantation 10 miles south of town, halting there until daybreak. They moved past Philadelphia, resting again until 10 o’clock that night. Two battalions of the 7th Illinois then moved on, ordered to pass through Decatur and hit the Southern Railroad at Newton Station, a major supply junction due east of Vicksburg. Grierson followed with the main column an hour later.

Preceding everyone, including the two point battalions, were nine men clad in Confederate uniforms. These volunteer Illinoisans, under the command of Sergeant Richard Surby, had been designated the ‘Butternut Guerrillas’ and were to prove their value as scouts again and again during the raid. This day they seized a telegraph station, preventing a warning of Grierson’s approach.

Grierson arrived at Newton Station around 6 a.m. The advance battalions seized the hamlet and captured two trains. The main column soon joined them. Here was property of legitimate military value, and Grierson had no qualms about laying waste. Two locomotives, 25 freight cars filled with commissary stores and ammunition (including artillery shells intended for the garrison at Vicksburg), were burned, along with additional stores and 500 muskets found in town.

A battalion from the 6th Illinois rode east, destroying bridges, trestleworks and telegraph wire. Seventy-five prisoners were taken, but were soon paroled. Several men found–and inevitably helped themselves to–a supply of whiskey, but all were ready to move out by 2 p.m.

The Federals continued south, soon reaching Garlandville. Here they were met by shotgun-wielding civilians, ‘many of them,’ wrote Grierson, ‘venerable with age.’ The Illinoisans were fired upon and one man was wounded. A quick charge broke up the untrained Southerners, capturing several.

According to Grierson, the prisoners were apologetic, ‘acknowledging their mistake, and declared that they had been grossly deceived as to our real character. One volunteered his services as a guide and upon leaving us declared that hereafter his prayers should be for the Union Army.’ Grierson used this as a sample of the attitudes he encountered among civilians during the raid, describing the ‘hundreds who are skulking and hiding out to avoid conscription, only to await the presence of our arms to sustain them, when they will rise up and declare their principles; and thousands who have been deceived upon vindication of our cause would immediately return to loyalty.’

To a point, the attitudes of the citizens of Garlandville must be taken with a grain of salt. They were, after all, surrounded by heavily armed soldiers whom they had very recently shot at and were thus liable to be disagreeable. Still, such dissension did exist in the South throughout the war. Poverty, food shortages, government policies that unfairly favored large plantation owners over poor farmers, destruction of home’s and livelihoods–all this was stripping away loyalty to the Confederacy from many Southerners. The people of Garlandville had been willing to fight to defend their homes, but once they discovered the raiders meant them no harm, the obligation to bear arms against them disappeared. This was not really, as Grierson implied, due to any latent loyalty to the Union, but was rather part of the quite human desire to keep a roof over one’s head and a moderate amount of food in one’s stomach.

The raiders rode another 12 miles, stopping that night on a plantation belonging to a Dr. Mackadora, 50 miles from Newton Station. Newton had been the primary tactical objective of the raid. After leaving there, Grierson had complete discretion as to his route and final destination. The ride south through Garlandville had been to find a spot to rest and forage. His men would not be on the move again until the morning of the 26th. In the meantime, the Butternut Guerrillas were out gathering information about Confederate troop dispositions.

One of the scouts, dressed as a civilian, turned north, back toward the Southern Railroad, to cut the telegraph and perhaps burn a bridge or trestlework. Seven miles from the tracks, he ran into a regiment of Rebel cavalry from Brandon searching for Grierson. They were riding directly toward the Mackadora plantation, but the quick-thinking scout bluffed them. Claiming to have seen the raiders recently, he sent the horsemen galloping off in the wrong direction.

Grierson soon learned that Pemberton had been reinforcing Jackson and points east with infantry and artillery. He decided to move southwest, crossing the Pearl River and hitting the New Orleans, Jackson & Great Northern Railroad at Hazelhurst. From there, he would flank Confederate forces and eventually join Grant at Grand Gulf.

Pemberton, though, had finally guessed correctly regarding Grierson’s intentions. He ordered Maj. Gen. John Bowen, commander of the Grand Gulf garrison, to detach seven Mississippi cavalry companies to intercept the raiders. This, in turn, further weakened Bowen, who would soon be meeting Grant’s far superior force in battle. Pemberton was in a no-win situation. He could hardly allow a thousand enemy troops to romp around behind his lines, but the only way to stop them was by diverting men from strategically vital areas. By now, there was more than a division’s worth of troops scattered about the state hoping to stop Grierson. This, of course, was the primary objective of the raid, beyond damaging Pemberton’s supply line.

Rested and reprovisioned, the raiders set out again at 6 a.m. on April 26. They crossed the Leaf River, burning the bridge behind them. Arriving at Raleigh, they captured the county sheriff and confiscated $3,000 in cash, and then stopped for the night at Westville.

On April 27, the Butternut Guerrillas were again dressed in Confederate uniforms. Moving ahead of the main column, they seized a ferryboat on the Pearl River, presenting Grierson with an easy method of crossing. Reunited here with Forbes’ B Company, the raiders moved on to Hazelhurst. Here a string of boxcars was burned, but the flames spread to nearby buildings and suddenly the whole town was in danger of going up. Grierson set his men to work alongside the townspeople, fighting to save Hazelhurst. A hard rain fell that night, helping to contain the blaze. It was not until well after dark that the Illinoisans could move on. Now their course was due west, toward Grand Gulf.

They continued west on the 28th. A battalion from the 7th Illinois was detached to double back to the railroad, destroying rails, telegraph wire and government property. The main column stopped at a plantation that afternoon, but the break did not prove restful. Without warning, the pickets were fired upon and Rebel horsemen charged forward, their sudden attack panicking many of the Illinoisans.

Grierson led a counterattack, and the Southerners, consisting merely of two understrength companies, were pushed back. The Federals kept pushing, driving the Rebels through the nearby town of Union Church and occupying it that night. The detached battalion rejoined them there.

The attackers were part of Colonel Wirt Adams’ command, the Mississippi cavalrymen detached from Grand Gulf. The bulk of Adams’ men were west of Union Church, waiting to ambush Grierson. A Butternut Guerrilla again saved the day, riding ahead in disguise and speaking with some of the Mississippians. Warned of the ambush, Grierson changed his plans. He made a brief demonstration to the west, then doubled back to the east. His final destination was now Baton Rouge. His men would have to ride an extra 100 miles, but the decision was unavoidable. Adams pursued, staying on Grierson’s tail as far south as Greensburg, La.

Five hundred armed citizens and conscripts awaited the raiders at Brookhaven, a town astride the Great Northern Railroad 20 miles south of Hazelhurst. The raiders charged into town, quickly ending resistance. The town proved to contain a ‘camp of instruction’–what would nowadays be called boot camp. Prisoners were paroled and the camp, along with the railroad and the telegraph was destroyed. Once again, flames jumped onto civilian buildings and once again, despite the loss of precious time, Grierson’s men helped to save a town. The raiders turned south, riding eight more miles before making camp at a plantation.

Elsewhere on the 29th, William Sherman was carrying out his demonstration near Chickasaw Bluffs. Farther south Union gunboats spent six hours bombarding Grand Gulf in preparation of Grant’s crossing. But the Confederate positions remained intact. Grant was forced to move again, intending now to cross at undefended Bruinsburg.

The raiders continued south on April 30, destroying bridges, water tanks and trestleworks, and burning the depot and 15 freight cars at Bogue Chitto Station. They reached Summit as sunset neared. Grierson ordered the destruction of 25 freight cars and a large cache of government sugar, but spared the depot itself. He did not want to risk a fire again spreading into town, and he could not afford to lose more time while his men fought the blaze.

Grierson ordered his men to remount–some were a bit unsteady in the saddle after discovering a supply of rum–and made six more miles before camping. On May 1 they turned west, then south, making a’straight line for Baton Rouge, and let speed be our safety,’ as Grierson phrased it. The raiders were to cover 76 miles in the next 28 hours.

They neared Magnolia and later 0syka, but both towns were bypassed because they contained enemy troops. About noon, they reached Wall’s Bridge across the Tickfaw River. Three companies of the 9th Tennessee Cavalry greeted them there.

Grierson’s lead company suffered eight casualties (accounting for nearly all the battle losses he suffered throughout the raid), but the Illinoisans pressed their attack against their outnumbered foe. The Confederate pickets were captured, then Grierson’s artillery rumbled up and shelled the enemy position across the river. A charge swept the bridge and sent the Tennesseans running, leaving a number of dead, wounded and captured comrades behind.

‘The enemy were now on our track in earnest,’ wrote Grierson. Captured dispatches told him that Rebel troops were closing in from all sides. He continued to gallop south, riding all that night, pushing his exhausted men to their limits. They crossed the Amite River at Williams’ Bridge at midnight, two hours ahead of a heavy column of infantry and artillery.

By now, the Confederates had plenty else to keep them occupied. Grant’s troops crossed the Mississippi on May 1 and were moving up to take Grand Gulf from the rear. Bowen moved his 6,000 available troops to Port Gibson, intercepting Grant. But the unfortunate Bowen, stripped of his cavalry and having received no reinforcements, was outnumbered 4-to-1. He fought all day, inflicting a disproportionate number of casualties, but was inevitably forced to retreat and abandon Port Gibson. Grant, at last, had a secure bridgehead on the east side of the Mississippi.

Grierson’s men reached Sandy Creek at dawn on May 2, surprising and capturing a Southern cavalry unit camped there. The camp, with 150 tents, plus guns, ammunition and documents, was destroyed.

The raiders kept going, surprising another cavalry unit at Roberts’ Ford across the Comite River. After a brief skirmish, 40 Rebels were captured along with their horses and equipment. They forded the river, with many of the horses forced to swim across the deep water.

The men reached their limit just six miles short of Baton Rouge. Grierson called a halt, letting them sleep alongside the road. Grierson himself wound down by playing a piano found in a nearby plantation house, but was interrupted by a picket shouting that they were about to be overrun by Rebels coming at them from the west.

Grierson guessed the identity of the approaching men and rode out to meet them. As he suspected, they were Union cavalry from Baton Rouge, riding out to meet the raiders. Grierson’s exhausted and filthy troops rode into the Louisiana capital at 3 p.m., greeted by cheering soldiers and civilians alike. They paraded around the public square, then found a magnolia grove south of town where they could simply collapse and catch up on two weeks’ worth of sleep.

Grierson’s raiders had traveled more than 600 miles in 16 days, virtually without rest and often limited to one hastily eaten meal per day. One hundred Confederates had been killed or wounded and another 50D had been captured (most of whom were later paroled). The raiders destroyed more than 50 miles of railroad and telegraph, 3,000 stand of arms and thousands of dollars worth of supplies and property. A thousand mules and horses were also captured. In addition, they had tied up virtually all of Pemberton’s cavalry, one-third of his infantry, and at least two regiments of artillery.

All this was accomplished at a cost of only three dead and seven wounded. Five men too sick to continue had been left behind, and nine men, presumed stragglers, were missing. The 7th Illinois’ surgeon and sergeant major stayed behind with a mortally wounded officer at Wall’s Bridge. Added to Hatch’s losses, the casualties numbered 36, only about 2 percent of the total command. Grierson was quite justified when he later remarked, ‘The Confederacy is a hollow shell.’ Rebels in Mississippi, as everywhere else in the South, were spread too thin to do their jobs.

Grierson suddenly and uncomfortably discovered he was a hero. ‘I, like Byron,’ he wrote his wife, Alice, ‘have had to wake up one morning and find myself famous.’ He was sent by steamboat to New Orleans, where he encountered ‘one continuous ovation.’ His picture was featured on the covers of Harper’s Weekly and Leslie’s Illustrated. He was breveted to brigadier general and later major general of volunteers.

Grierson continued to serve with distinction, commanding first a division, then a cavalry corps in Tennessee. Despite his continuing distrust of horses, he remained in the Regular Army after the war, battling Indians as a colonel with the 10th U.S. Cavalry. He retired as a brigadier general in 1890 and died in 1911.

Following the raid, Grant continued to advance eastward. Joined by Sherman’s division, he now had 40,000 men in Mississippi. Pemberton had 30,000, but many of them were scattered across the state and he lacked time to concentrate his forces. Bowen was forced to abandon Grand Gulf, and Grant was virtually unopposed as he marched to Jackson, burning that city, and then swung west to besiege Vicksburg. He advanced with a supply line–Grierson had helped to demonstrate that troops could live off the land, appropriating food from farms and plantations as they progressed. It was a lesson dramatically learned and daringly taught–that others would study in the flame-darkened days to come.

This article was written by Tim DeForest and originally appeared in the September 2000 issue of America’s Civil War.

For more great articles be sure to pick up your copy of America’s Civil War.